Living the Rock and Roll Lifestyle

By Richard Flohil, The Canadian Composer, January 1975, transcribed by John Patuto

Toronto Airport, at 11 in the morning, is almost deserted. In the arrivals area, waiting along with the ladies from the rent-a-car companies, are three girls-their men are coming home from work.

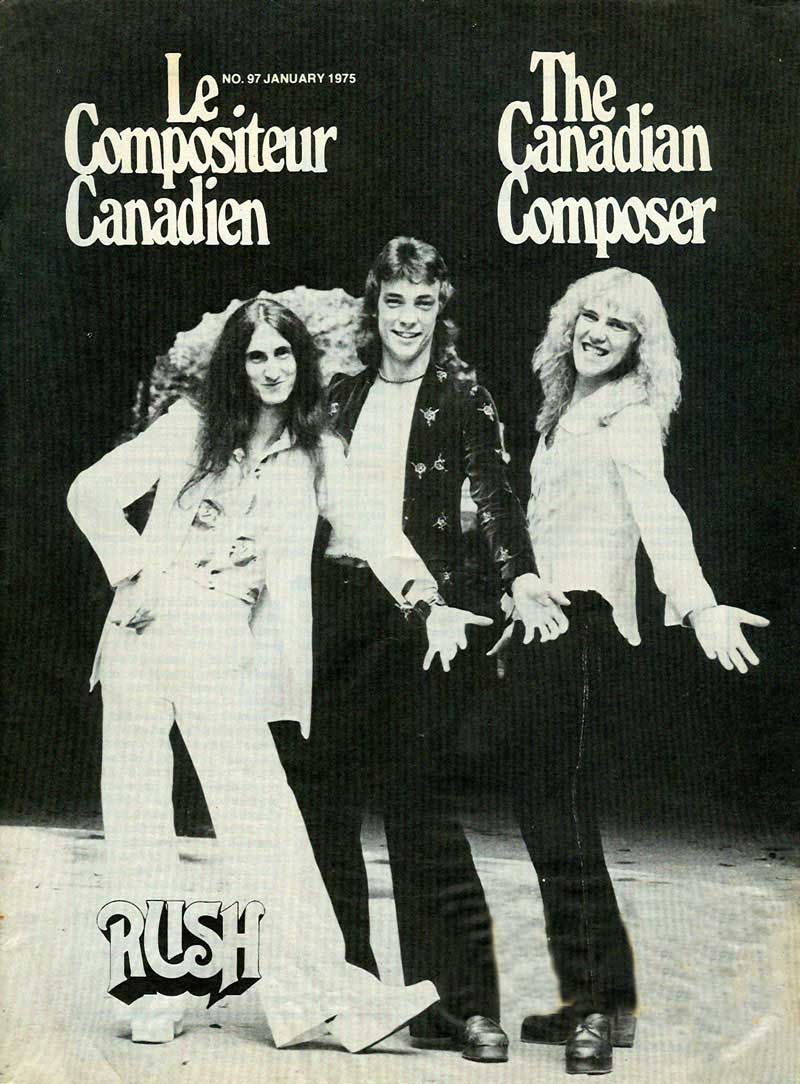

The men are Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, and Neil Peart, their work is rock and roll, and soon American Airlines will deliver them from Columbus, Ohio, safe and tired and weary from six weeks on the road.

Lifeson, Lee, and Peart are the members of a band called Rush. In the last six weeks they've been to New York and New Jersey, California, and an endless string of states and cities. Among them St. Louis, Houston, Dallas, Los Angeles, and dozens more.

Through the barrier windows, the girls watch as the three members of the band, their road manager, and three roadies, gather in a solemn conclave with customs officials. Check lists are checked, clipboards are consulted. Eventually the musicians are free to leave, and resplendent in velvet jackets and patched jeans, long hair, and stacked-heel boots, they enter the real world, unencumbered by nosy customs men asking silly questions.

The roadies are left, filling in forms, opening up instrument cases, boxes of patch cords and microphone cables, and enormous yellow-and-silver custom-made crates, all stencilled "Rush Productions, Toronto", full of speakers and amplifiers. They'll be here for a couple of hours yet, before it's all loaded on a rented truck, and shipped off to the next gig.

In the deserted arrivals hall there are hugs and kisses. They leave quickly-time is short; Lifeson, Lee and Peart have just two days off. And then it's back on the road again.

Rush is not the best-known band in Canada by a long way. For a start, they play the sort of music that the local critics, without exception, hate: Heavy metal rock. Canadian radio stations play very little of it, writers off-handedly compare Rush to Led Zeppelin or Black Sabbath or Uriah Heep (three British groups pre-eminent in the idiom) and go on to write about "noise bands", "lack of subtlety", "primitive instrumental techniques", "screeching vocals".

Most critics and most disc jockeys and radio programme directors are in their early thirties, of course-and nowhere does a generation gap evolve so quickly as it does in the world of rock. But whatever the critics say, whatever they play on the radio, the word gets out-by word-of-mouth, rumour, osmosis, or whatever-and the heavy metal bands are incredibly popular.

The Rush story is simple enough - and probably common enough. Three friends from suburban Willowdale at the north end of Toronto get together in high school, and drive their parents nuts with the noises they make down in the basement. After a while, they play a few gigs at the school, and all their friends say they're far out. Then they get ambitious, and join the union. Soon, they're deep in debt to the instrument store, and there's a battered truck to take the band and the gear to one-nighters in Oshawa, and Peterborough, and Delhi, and Midland; small-town Ontario where the kids are dying of boredom and where a band at the high school is the social event of the season.

By now, this particular trio has a name - Rush, with its connotations of high-style good times, speedy energy, and sheer sassyness, seemed to be a good name for a band like that. No one knows who came up with it, now-and the only annoyance has been the discovery of another Canadian band (this one from Montreal) that's on the road calling itself Mahogany Rush. By now it's too late for either band to change; both groups live with the inevitable confusion.

Rather before the legal age, the band is playing Toronto bars as well as those one-nighters-the pubs that teenagers with their older sisters' ID cards can get into, where the local critics wouldn't be seen dead, and where the kids might tell you that the local critics are dead.

Eighteen and over (or faking it), these kids are breaking away from home and school and family ties, growing up and away-and this band and this music are just right. It's rough and ready, loud and proud, and simple to the point of thundering repetition.

Rush plays this circuit for three years, fully professional, and with the publicity photographs and the invoices from the instrument store to prove it. If you can keep up your energy levels and your enthusiasm, all this work tightens up the music, improves your instrumental techniques, teaches you how to write and rehearse and how to work with an audience.

Early in 1973, Rush - with a lineup which consisted of Geddy Lee on bass and lead vocals, Alex Lifeson on guitar and vocals, and John Rutsey on drums - finished an evening's work, and went into Eastern Sound in Toronto right afterwards. Eight hours later the band had part of an album, but after living with it for a while, the band decided they could do better. Clutching the original tapes, the band went back into the studio - this time Terry Brown's Toronto Sound - and re-recorded some of the material, and re-mixed the rest. Three days later, they had an album.

Various Canadian record companies heard the tape, and offered the standard "page-one" deals that most "new" Canadian bands are handed. Ray Danniels, the group's manager, decided to pass-and with his partner, Vic Wilson, set up Moon Records (and Core Music to publish the material) and put the album out themselves. Eight cuts (some as long as seven minutes); all the songs written by Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson, except one, In the Mood, issued as a single and written by Lee on his own.

The reviews were sparse, but good. Playlist was complimentary; the Ottawa Citizen called Rush a "still-Canadian group charged with life", and this magazine described the music as "loud, proud and take-it-or-leave-it, played with shrieking energy and some musical skill." Canadian radio stations, by and large, ignored the album and the single.

But an album is an album, and Danniels and Wilson had something to sell at last. In Cleveland, where one radio programmer on an underground FM station loves Canadian music (Donna Halper at WMMS), Rush became a local phenomenon, and the album, imported into stores from Canada, became a best-seller.

In New York, Danniels and Wilson made a deal with Ira Blacker, powerful executive vice-president of ATI, a major American booking agency-and Blacker moved fast in a way that only New York heavies move when they figure it's worth their while. First of all, his agency signed the band, and then Blacker sold the record - for a six figure advance - to Mercury in Chicago, who had made several million dollars with another Canadian group, Bachman-Turner Overdrive. (Later, Blacker quit the agency, and set up his own management company. Rush, needless to say, became one of his first clients).

Rush was ready to invade the United States.

First, however, some changes had to be made. John Rutsey, on the brink of the first U.S. tour, left the band. Press releases talked about "musical differences", but in fact Rutsey is a diabetic, and his longtime friends knew that his health would simply not stand up to an extended tour.

Neil Peart, an articulate, experienced drummer from St. Catharines, Ontario, got the job-and immediately Lee and Lifeson began to change their approach. Peart, simply, was a more flexible drummer, technically more proficient, and able to add a variety of new rhythmic changes to what is, essentially, a rhythm group.

Visas in hand, Rush went to America. Second or third (and even, occasionally, fourth) "on the bill to every heavy metal rock band; touring the States, Rush just stood up there and did what it had always done-pounded out the music, got the kids up on their feet, and delivered the goods.

Fortunately, the musicians in Rush are young themselves-Lee and Lifeson are in their early twenties, Neil Peart a couple of years older. Frankly, they need to be.

Playing is not the part of being a rock and roll musician that makes it the physically demanding occupation that it is, even when you play with the energy that Rush uses. What kills the brain cells and yellows the flesh is the travel-the constant time-warp of new airports, new cities, new rental cars, new hotels (even though most Holiday Inns are the same), new places to eat, new college reporters looking for new insights for another new interview, and new fans wanting just a few minutes (or hours) of your time. After that, playing is simple.

Rush has a road manager - an experienced, tough, and cheerful young man called Howard Ungerleider - and three roadies to shift all the equipment about, set it up, and tear it down again, but the schedule has been exhausting. In the middle of it all, the band has been writing new material, and doing television as well. They have taped shows in Canada for Keith Hampshire's Music Machine on CBC, but they've also taped sets for the big three American shows, In Concert, Don Kirshner's Rock Concert, and Midnight Special, which have taken Rush into millions of American and Canadian homes in the past few weeks.

And the record is selling like hot cakes. All it takes, say the experts, are lots of in-person appearances, and some good television exposure.

Two days after coming home, the band is at work again. Massey Hall, Canada's most venerable and best known concert hall, is sold out - Rush is sharing the bill with Nazareth, a Scottish rock and roll band just beginning a coast-to-coast Canadian tour.

The equipment is spread across the stage-masses of stacked speakers, amplifiers, two drum kits, thousands of feet of cable, lighting booms. In the audience, expectant kids bounce giant balloons and throw paper darts; this is party time.

The lights dim, the follow-spots pick up the musicians, the crowd begins to yell-and suddenly you begin to understand why the group's name makes such sense. The volume is incredible; thundering drum patterns, skittering and screaming guitar lines, Lee's shrieked vocals, high in the upper registers. Instinctively, you know why the critics hate it and the kids love it-the noise and the sheer flash of it all.

The set runs through the material on the album, with two or three newer pieces. The pace and the volume increase, and at the end, with the spotlights criss-crossing the audience and the stage, the band reaches a shattering finale, with the crowd standing and cheering.

And Geddy Lee, direct from Willowdale, throws his head back and laughs at the sheer fun of it-at the rush, if you will-and shouts: "It's great, it's just great, to be home!"

The future? Well, Rush is part of a world where fads and fashions change faster than they do in the women's wear business, and they know it. The constant touring exposes the band, the television shows build its reputation, the record sales help-but everything depends on what the band can do now.

As you read this, in early January 1975, Rush is in the studios with Terry Brown. This is the second album, and it has to be a show-stopper. It will have to have at least one hit single on it. The material-written and honed in performance for the last eight months or so-has to be exactly right.

This time, they're taking more care; everyone knows that this one is more important - no, this one is vital. This record can make Rush, or consign it to the list of good bands who came close, but never quite pulled it off.

If Rush - and Terry Brown, and Vic Wilson and Ray Danniels and Ira Blacker and the roadies - if they can all do it, then Lifeson, Lee and Peart will become millionaires. Just like the guys in The Guess Who, just like Gordon Lightfoot, just like Randy Bachman and Fred Turner. That's a sobering thought. Indeed.