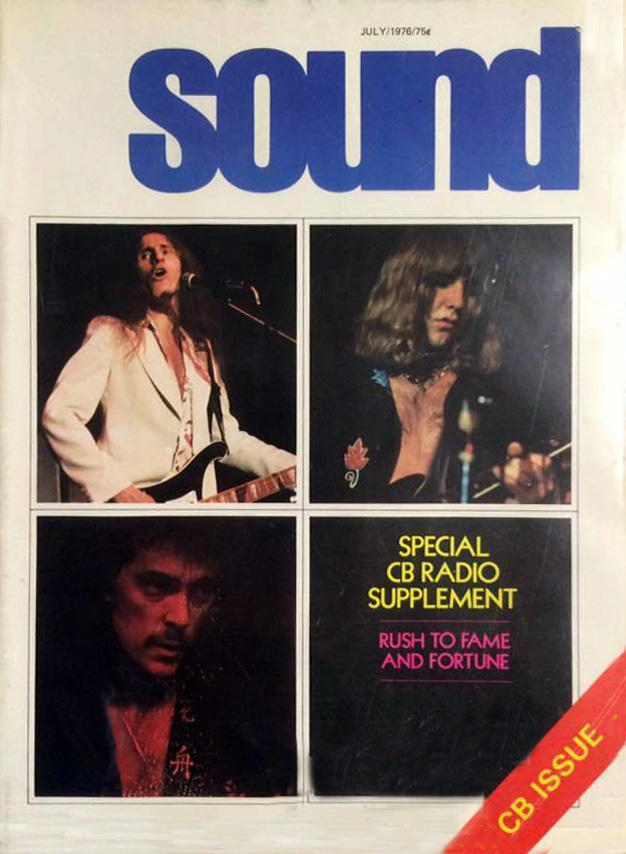

A Headlong Rush To Stardom

For years, Canada's critics have scoffed at Rush, the Toronto-based power trio. Now Rush has turned the tables.

By Jim Smith , Sound, July 1976, transcribed by John Patuto

Five minutes before curtain time and the audience is getting restless. This particular audience is not one which sits contentedly during intermission. For the most part, it's a young audience, drawn from the classrooms of Hamilton high schools, badly disciplined, and, judging from the aroma in the washroom, mostly stoned. The usherettes at Hamilton Place, swank civic concert hall, in Ontario's Steel City, spend most of the evening shaking their heads with dismay.

Off to either side of the stage, the p.a. has been warming up for the past 15 minutes. The speakers are banked to get the widest throw and the most power; they are also hissing with white noise at an ominously high volume, prelude to the acoustic onslaught to come.

Rush do not take the stage so much as attack. The lights and sound snap on simultaneously. Alex Lifeson rips off a savage guitar riff. Geddy Lee drags out some heavy bass notes, and Neil Peart slams the drums mercilessly. The audience is roaring approval, but no one can hear anything. And, for several minutes after Rush has left the stage, even after the hall has emptied, those who have sat through the concert will hear nothing else.

In a word, Rush is loud. Stripped of adjectives, taken down to the essentials, Rush is a powerhouse band, the loudest and most savage of the Canadian groups. Louder, more visceral than Bachman-Turner Overdrive, louder than Mahogany Rush or April Wine. Louder than A Foot In Cold Water. Louder, in fact, than loud.

In the beginning, Rush had little going for them, not even a distinctive name. (Even today, there is a tendency in some circles to confuse Rush with a Montreal act named Mahogany Rush.) They were simply three high school kids with no inhibitions to hold them back from playing the wrenching rock that presented an unappreciated and largely untapped market. So the critics laughed at them: the people bought them. Three albums in a row sold remarkable well: the second album, Fly By Night (Mercury SRM 1-1 023), has become a gold record in Canada. The concert audiences grew larger, to the point where Rush was selling out venues like Massey Hall. And, finally, the band created 2112 (Mercury SRM 1-1079), a remarkably sophisticated blending of hard rock and intelligent musical approaches a la Led Zeppelin.

All of a sudden, Rush has become a musical force that must be taken seriously. As this comes from the typewriter 2112 has entered the Billboard album listings at number 62 with a bullet, by far the best performance by the band yet in the United States and solid proof that they have, at last, achieved commercial viability throughout North America.

Neil Peart joined Rush slightly less than two years ago when John Rutsey, the band's original drummer, walked out. The band had one album, the hastily-recorded and unrewarding Rush (SRM 1-1011), and little else. Peart became considerably more than a drummer, however. Today he is the sole lyricist, giving the band a pseudointellectual verbal approach that is considerably advanced over the band's music. And he has become a seasoned spokesman, the kind of person who can field tough questions with ease and turn easy questions into solid hits for the band. Right now, Neil is speaking from Duluth, Minnesota where Rush is due to open for Blue Oyster Cult later in the evening.

"Rush succeeded", Neil believes, "where other bands didn't for a lot of reasons, some of them outside the band. Part of our success had to do with good timing. A large part of it was due to good management. And the most important part, I suppose, was the fact that we worked very hard to get where we are now. We have been touring constantly since the first album was released, playing for thousands and thousands of people.

"It seems to me that there are only two ways that a band can become successful. Either you concentrate all your energies into getting a hit single with massive airplay, or you get out and work a lot to get person-to-person contact with audiences. The latter approach seemed to be our only option. We're not inclined towards sounding like a top-40 band. We may get a hit record eventually, but it will only be because the radio stations have been forced. I think Aerosmith and Kiss are good examples of that: radio stations didn't play those bands until their followings became so large that they couldn't be ignored."

But let's start at the beginning. Well, not exactly the beginning, since that was more than seven years ago, when Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson, ad John Rutsey first created Rush. Rather, the Rush that was born two years ago with the substitution of Peart for Rutsey. Peart argues the band's current philosophy of music.

"Ever since the three of us got together, it has been our objective to take the natural thing that comes to us - which is playing hard rock - and making it more progressive, or polished. We are trying to make our music as good as it can be within the confines of that well-known genre of music, heavy metal rock.

"Now there are limitations involved in having only three musicians to the band. But I think that the limitations are balanced out by the nicer parts of the concept. The three of us, for instance, are creatively balanced because we all write and we all arrange and we're all involved in the music right from the birth of an idea through to its recording. Right down to the very end, it is all split three ways, which is an even division that can't be found in larger bands. We have thought about adding a fourth member, but it would really tend to upset the chemistry and destroy our balance.

"Instead of adding that extra man, we're going to try to expand on the possibilities open to the three of us. We're going to be looking for new textures and new sounds. We're going to be adding different instruments that will be good for our sound."

Instruments are most critical to the success or failure of a trio than to larger groups. Three musicians can only make so much sound so it comes down to a situation where the sound must be recycled through various machines that stretch out the notes and give a hangover for continuity. In Rush's case, Alex Lifeson already had two Echoplexes, running at different speeds, hooked up to his guitar.

More than instruments, however, the rock trio relies on volume. Rush is loud for a better reason than simply enjoying volume: the trio relies on volume to survive. Or, as Neil puts it: "It must be understood that, for a trio to give a full sound, it must play at a pretty loud volume. You'll notice, I think, that most of the bands that have been playing at high volume over the years have been smaller-sized bands with a single melody instrument. You only have to look at the Who or Cream or Hendrix or any of those bands to get the point".

"However, it's become a situation with us where it is no longer simply requiring volume to survive. It's getting to the point where the volume is the contrasting texture. Okay, we all recongnize that the problem with substance is that it has to be dynamically balanced to give it the impact we need. We have to be able to play softly initially and bring up the volume at the end as the climax to the show, something we haven't fully mastered yet. It takes time to develop those careful dynamics. However, we are working towards it as well. "

Volume can create problems for a trio, too. The Hamilton Place concert was not memorable for acoustic fidelity. "It's a problem we've encountered with several new halls," Neil admits. "The sound goes straight back and you get a good, clean attack. But there's so much craziness at the end of the hall that the sound reverberates and accumulates. We would much rather play in older theatres."

The early simplicity and continuing fascination with high-decibel playing have been responsible for numerous false impressions. Among those impressions lingers the belief that musicians such as Rush must necessarily worship at the altars of Grand Funk and the James Gang. Neil, however, reveals some unlikely influences.

"Naturally, in the beginning, we tended to emulate the musicians who were on top of the musical pile. They were musicians like Jeff Beck and the Who and Led Zeppelin. In that respect, I don't believe we were any different from all the other young musicians of the day. But we are discovering new bands every day who are doing worthwhile things and becoming influences on us.

"It has reached the point where it is impossible to exclude any band as an influence. Bands like Genesis and Pink Floyd have been influences on our standards even if they don't have a direct impact on our musical style. Professional standards are something that every band must live up to and today, as we develop our own style, it is becoming more the rule that the principle influences are on our performing techniques than our music."

The culmination of those myriad and diverse influences is 2112, a "concept" album consisting of a futuristic suite of the same title on the first side and five individual tracks on the second. It is, as we've noted, the album that has established Rush as a band of some artistic integrity, an album which has taken them beyond the confines of straight-ahead rock.

"We sat down and decided among ourselves that it was time for us to lay everything on the line," Neil contends. "We had been working towards something a little more ambitious on each of the previous two albums. We simply decided that 2112 would have to be the realization of all our hopes. "

Along with the realization of the hopes, however, there were a few new problems. In particular, 2112 appears to have cost Rush the backing of many young fans, the type that Neil describes as "being there just to shake their heads to the same beat for five minutes. Diversifying our music has cost us a few fans at that younger end of the range. But, as compensation, we're picking up lots more sophisticated fans at the other end of things."

2112 has also brought out into the open the band's objections to being compared with B.T.O. Both bands are signed to Chicago's Mercury Records and both, of course, are Canadian bands playing fairly hard music. But Neil and the others see red when compared to the Vancouver quartet.

"We get very sensitive when we're compared to B.T.O. because they're the exact opposite to us in musical direction," Neil argues. "Our values and our beliefs are totally different and there's probably no one whom we would less like to be compared with. I guess the simplest way of putting it is: for us, it's music first."

Which is not to say that there are not still detractors who would suggest that Rush has somewhat lower musical standards than, for example, the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Or the Smith's Falls Chamber Society. But that does not alter the fact that Rush do take their new position seriously. So seriously that they are looking abroad for new projects.

"2112 is probably the last album that we'll be doing in Toronto. We now think that we can get a few different sounds into the music by changing studios. We've done four albums at the same studio (actually, they have only recorded the three newest albums at Toronto Sound Studios: the first was recorded at Toronto's Eastern Sound Studio) now and it seems like a good idea to look for something else.

"Trident Studios in London is the facility that we're most interested in right now. I've heard some beautiful sounds come out of that studio and I'm quite anxious to get in there and try it out. Our producer, Terry Brown, was trained in London's studios, so it will be like old times for him."

For Rush, it will be just one more sign of their attempts to stay ahead of the times.