Life In The Fast Lane With Rush

By David Farrell, Record Week, August 22, 1977, transcribed by pwrwindows

Chicago's IBM building stands loftily in the center of the downtown business section of this industrial city. Halfway up its icy cold glass face is the headquarters for Mercury Records Inc. One of the few major U.S. companies to locate outside of the music hubs (New York, Nashville and Los Angeles), the flow of traffic is slower, the pace of work more humane and the reception given to visitors almost genteel. Off the main corridor, past the wall of gold and platinum records, beyond the main boardroom where the deals are signed and marketing strategies wagered, press director Mike Gormley ends off the day 's messages stacked ominously on his desk. A onetime musician from Ottawa, and former journalist for the Detroit Free Press, Gormley looks harsh under the white fluorescent lighting; but the day is far from over. Couched around the room, various members of Max Webster are stretched out, chomping on some fast food stuffs brought in and washing all down with coffees and Coca Colas. Life in the fast land ain't always dinner at the Ritz.

The familiar face of Tom Berry strides in through the open doorway, Mike Tilka grins between bites and asks what 's next on the agenda. Berry is trouble - shooter for the band, as well as director of Anthem Records which handles Max, Rush, Foot In Coldwater and Liverpool north of the 49th. When in the U.S. and Europe, however, Mercury is the label that carries the weight, handles the records and promotes the groups.

Berry confers privately with Gormley, then announces that a sound check is scheduled in 30 minutes at the Aragon ballroom, "then we're all back to the concert site." Traffic is slowing down to a crawl outside as the Rush tour creeps slowly toward 4 p.m; the party quickly fans out the main doors and into the awaiting cars.

BACK UP TOP, however, Anthem's brass and mainstays behind power - trio Rush, Vic Wilson and Ray Daniels are banging out conditions for promotion with Mercury People for Rush's upcoming tour in Europe and Britain. Gormley is highly optimistic about the first tour, sensing that what has gone down in North America over the past 12 months could well be the tip of the iceberg of what is yet to come.

As he counts down the success story the label has had with the trio over the past year, the drone of the local FM station suddenly cuts out and Geddy Lee and Neil Peart start rapping about their day at a local high school in the area. There's a guy in the office from Circus magazine to write a story about the visit and his ears perk up immediately. In the August issue of the same magazine he was to write of the trio's institutional visit:

"The Plan went something like this: Hersey High, being one of those Progressive Centres of Higher Learning found in the affluent suburbs of major cities, features a couple of courses on rock 'n' roll ("Boogie, It's History and Social significance in Western Civilization").

"These courses are taught by one Lyne Trainer, an English composition teacher who came up with the terrific idea of bringing in a Real Rock Band for his inquisitive minions to interrogate about the deeper meaning of pumping 30,000 watts through a couple of hundred loudspeakers at 10,000 pairs of drug-benumbed teenage ears".

Following this exercise in frustration, drummer Neil Peart put the whole affair down to "so much nonsense." The band had been duped and the end result was that a solid opportunity to get a few of the facts of life across to the "minions" was lost. The whole shelf of thought buried in Anthem, 2112 and Temples of Syrinx gone by the wayside in favour of uncovering the vital fact that Rush dig fast cars, and yes, Alex Lifeson does have a woman in his life.

LATER that same night, out of earshot and sight of the towering IBM building, at the Aragon Max is winding up its set in the rock 'n' roll hall. Drugs aren't a big problem here for this is the doorway to the mid-west ("wild west country" as Ted Nugent likes to call it). Booze is the working man's milk down here and, since vapour is actually falling down from the ceiling, nobody's pushing to start a fight. Actually, the floor is calm, most are sitting down taking in one of the last song's of the band's set, "Gravity".

Backstage: Alex Lifeson and Geddy Lee are warming up the hands and checking over the roomful of guitars set carefully on stands. As soon as the lights go on the audience roars out, at first applauding Max then it's "RUSH."

It is the first night of two at the 9,000 capacity hall. It is also the last city on the tour before a brief break and then off to Europe. By the end of the night, Rush will have performed before some 200,000 on the five long months of road combat. (There isn't a real break in the tour for another three months ahead!) "That's nothing," remarks Alex flatly, "we've been doing this for six years and I can't say we've got any regrets. We started off with a rent-a-truck and a handful of bar gigs in Southern Ontario. Now we've got a full-time crew on the road, our own camper and a loyal following in just about every city we play. It's not as if we're going backwards."

Backwards is hardly the direction Rush has moved in since discovery in 1973. Not counting the latest album, A Farewell To Kings (shipped gold day of release in Canada), four out of the five albums available are now gold in Canada and the last three albums have sold collectively well over one-million units in the U.S. With the informal break-up of Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Rush has become heir-apparent to BTO's rockpile throne. Similar to BTO, Rush gained much of its initial public acceptance in the U.S., by touring its backside off and has earned little else but scorn and criticism by the press at home. If the press is venomous in its bite, at least it had a reaction. The radio side is even worse. While Paul Anka can stop off in Canada once every blue moon to buy a greeting card for his mother and earn a packet off the CBC for some television spot, his records are played round the clock by commercial radio. He collects his royalty cheques in the mail in California and loses 10 percent on foreign exchange. Rush makes its home here, is lambasted by the press and totally ignored by radio jocks from the Atlantic Ocean to Vancouver Island.

The fact that Rush can sell out Massey Hall, the Concert Bowl and now plays the exhibition stadium ground is totally irrelevant to top-40 and "progressive" radio. Until the band sells out the Pacific Ocean marina, Canadian radio programmers just don't want to know about the band. Two-hundred and fifty thousand album sales mean nothing. Ted Nugent sells a million and they don't want to know about him either. It's Fleetwood Mac and "much more" Fleetwood Mac.

Perhaps it is a bit unethical to take a stab at the radio and press for ignoring this power-rock trio, but, then again, Canada has never been known for playing footsies with its bed-mates. If a band gets successful in Canada, give them the boot and do everything in one's power to ignore the fact. That, at least, appears to be the status quo conscience when dealing with a situation such as Rush.

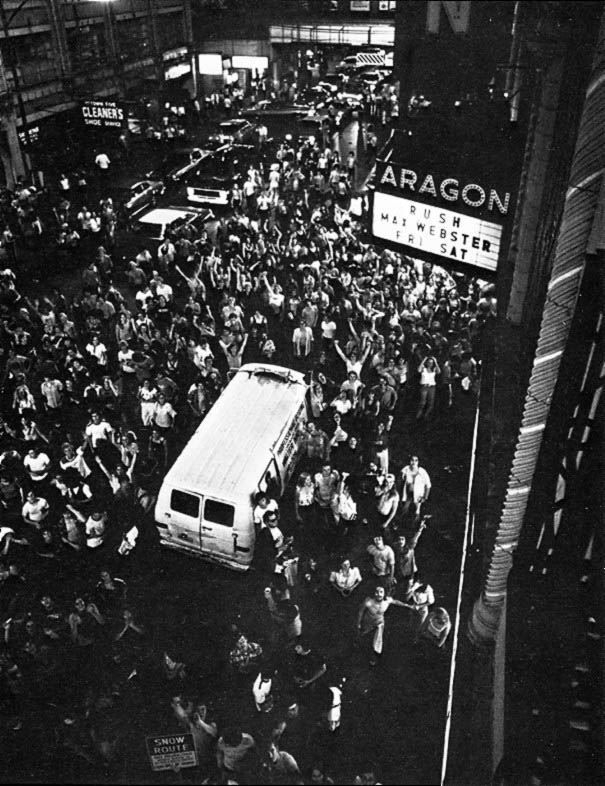

DEVASTATING is the only way to describe the effect Rush has on its audience. In Chicago the fans jammed the narrow street leading into the Aragon and jammed the street after the show. Standing on the balcony leading off the dressing room, Alex, Geddy and Neil bowed to the collective throng, floating an autographed paper plane down into the street with a roar of approval shooting back up through the hot, still air. It was the same way when I first saw the band at Massey Hall. It takes a certain appetite, a certain type of spirit (no pun intended), a degree of revolutionary spirit to attend these kinds of shows. We're not talking of tweed and satin dressed credit-card carrying patrons at these kind of shows. This is music of the people for the people. The Karl Marx of the music industry. In the same circle are such names as Nugent, Dave Byron, Aerosmith, Led Zeppelin, Moxy: the axes play wide, the drums are all stick action and the bass comes through like some deranged gorilla aping Idi Amin Da Da in a basement coffee house in Istanbul. It's hard core stuff and "please" and "thank you" know no translation in this dictionary of thought. So it was in England. If the mid-west is buffalo country, then Sheffield, Cardiff, Liverpool, Newcastle, Leeds and other blue collar centres in the U.K. are pure, unhomogenized punk centres where the only bars known are buildings that sell booze. In this kind of environment Rush excels.

And so it was in Britain and most centres played in Europe; In the venerable Sounds magazine, Geoff Barton was to pen of a date in Sheffield: "Just after 9.00 the main lights went out, applause started, cheering began, a voice boomed from the P.A. From Toronto, CANADA, will you please welcome - RUSH! ........ Suddenly, Lifeson's guitar was back in action, the riff to Bastille Day began. Suddenly, the crowd went bananas. The storm began.

New Music Express termed another concert, "The Rush Phenomenon" while the more staid Record Mirror wrote of "delirious kids" rushing the stage in Manchester and put the whole scenario down as being "most impressive".

There is a dichotomy at work in Rush which is not immediately apparent and thus passes unnoticed by critics' eyes and ears. The distinction, however, is such that it separates this trio from the pack, and is the essence of a fan's worship. The side that is the most apparent, the dominant macho pose that so incenses critics, of course, is SHEER VOLUME. The amplifiers are built to suck up electric power, digest it, then wham it out past the main intersection of town. At first it was as metallic as the hull of the Edmund Fitzgerald, then slowly it gained colour. The first time is witness to the Stelco approach to performance; at around the same time, bands such as Deep Purple, T.Rex, Black Oak, all were experiencing a new birth as previous legends fell back in their kitchen chairs too wasted to move. Album two was another story and ranks as one of the band's finest accomplishments thus far. Fly By Night finds Rush transcending beyond mere repetition, and seriously attempting to conjure a philosophy with music and words. Hence the opening track, "Anthem ." Alex Lifeson penned this with a little help from friends, in Beamsville, Ontario, of all places. Utopia, Ontario, as the life up there turned out to be and with Neil Peart the two delved heavily into surreal fiction (philosophy and good sci-fi). So came to be the imprimatur of the band's finer side.

Caress Of Steel, beautifully illustrated by Hugh Syme, finds Alex Lifeson experimenting on the guitar, acoustic bridges being introduced into the final batter. And again, three more songs destined to become hits in the underground. Herein can be found the original versions of "Lakeside Park" and "Necromancer Into Darkness" (the prelude to 2112 and the birth of a new seriousness in the band). Released just over a year ago, the album details life in a technocratic society and has become the all-time fave in concert for the band. It also propelled Rush from opening act to a headliner in Canada and the U.S.

In the band's first major media press conference following the release of the live album, Lifeson admonished that 2112 was the guide post for the future. The general feeling within the trio was that the live album marked an end to an era.

A FAREWELL TO KINGS is for Rush what Sgt. Pepper was to the Beatles. Not having heard it at the time of writing, this writer has the innate belief that it will deliver the goods. From beginning to end, the trio has treated the subject matter with almost gentlemanly detachment. Every facet in its way was treated with calmness. Plans were actually underway for a return tour even before Rush finished rehearsals at the Rockfield studios where the Farewell LP was recorded. The studio lies couched between the Welsh mountains in a setting right out of Barry Lyndon.

Cat Scratch Fever is not the Rush style of doing things. Ted Nugent's mistake is that he must now live up to his high-rolling public image and that can be a killer. Those UPI shots one sees of Robert Plant (Zeppelin lead-vocalist) strolling with his wife and the sheep strung out across the spread, that's more the Rush style of living life.

In closing this brief profile on the band's rise to fame, a mention to Terry Brown is an absolute must. Perhaps best known as the key man behind Klaatu, Brown has proved to be a brilliantly perceptive translator for the band and has nurtured them from their beginnings and taught them to constantly work toward progress. Beyond a shadow of a doubt, Rush has mastered the electronics of rock and have now spun on to compose with it as if it were an instrument, which it is. In the past year the inflow of new equipment has allowed the band to generate a far more complex series of sounds from its battery of speakers. Pedal synthesizers, double-necks with multiple sustain pedals, a mini-moog: all of this enables the players to further a show.

AUGUST 23: Rush gambles its reputation in home town and headlines the CNE Exhibition with Max Webster supporting act on the bill. The date is important for the band for it points out in no uncertain terms their power to command an audience. Kansas, equally big in the hard rock cafes in every town, were chicken to take the gamble of leading the show and lured Canada's April Wine to second on the bill. Max attracts, but they haven't sold the albums April Wine has.

IMMEDIATELY FOLLOWING: August 23, A Farewell To Kings is shipped gold day of release and it is second day on the road for a tour billed as A Farewell To Kings World Tour, 1977-78. The band winds north to the Lakehead and then west to Victoria. A Foot In Coldwater rides with the band as far as Winnipeg and then Max Webster is in the saddle to re-conquer the fans pepped up by their recent appearances with Styx. By late spring the following year it will be back into Europe and Britain. Life in the fast lane has proved good to these three gentlemen from Toronto and the odds are in favour of even bigger success ahead. As Wilde testily advised his audience one time, "Art should not attempt to reach down to the public, the public should reach up to the art." While it might sound sacrilegious to call the Rush sound art, remember people once thought the world was square. Perhaps it still is, on both counts.