Rush Relive Their Early Years

'Archives' Combines Canadian Trio's First Three LPs

By David Fricke, Circus, May 11, 1978, transcribed by pwrwindows

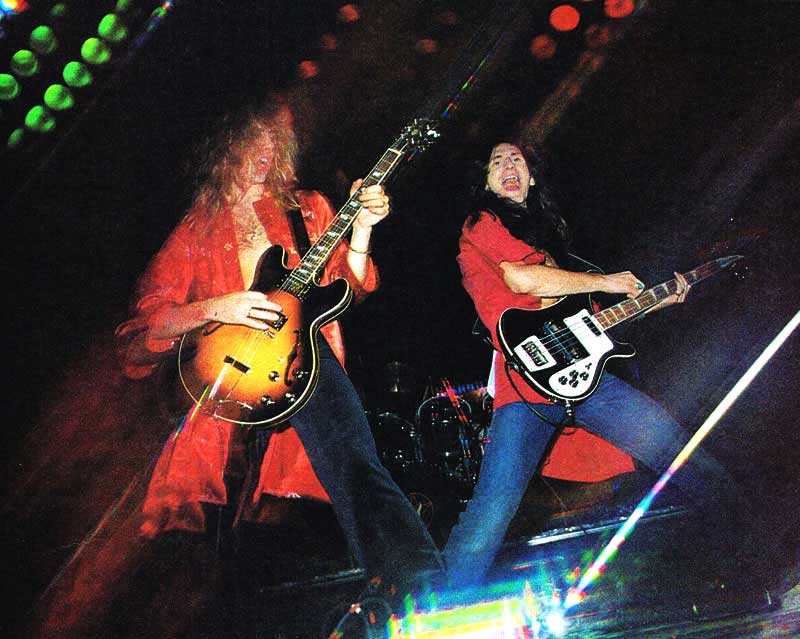

Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee and Neil Peart (hidden behind the drum kit) began a long climb to recognition on their own Canadian label with 'Rush.' Mercury signed them, once they saw how well Rush drew crowds in the States-especially on the tough-to-please midwest tour circuit that broke-Nugent, REO Speedwagon, Bob Seger, Aerosmith and dozens of other hard rock acts.

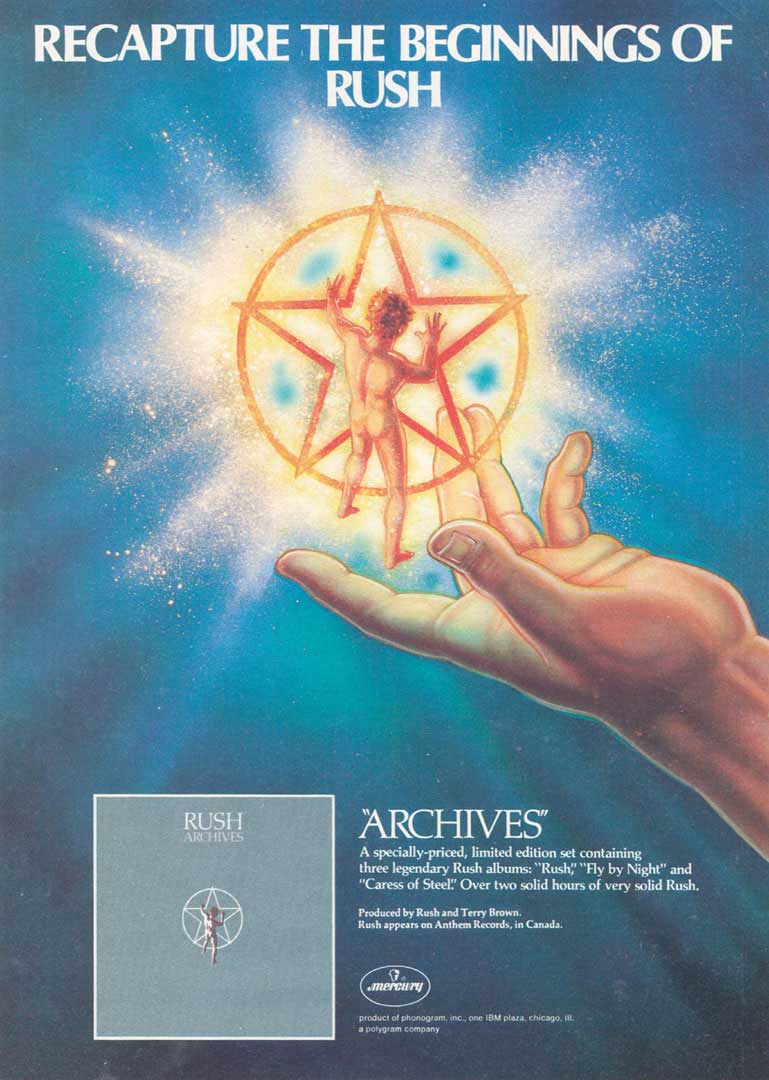

Rush's first three LPs, 'Rush', 'Fly By Night' and 'Caress of Steel,' have been packaged as one, low-priced triple LP, 'Archives,' to give latecomers to the Canadian trio a rush course in the heavier points of hard rock.

Survivors in a business that feeds on the young and ambitious, the Canadian rock group Rush now stands as North America's premiere power trio.

But that lofty position is not built on the inflated promotional muscle of record company money or hype. Instead, guitarist Alex Lifeson, bassist Geddy Lee, and drummer Neil Peart subscribe to the theory that their long path to fame was originally paved with the hard-earned dollars of unshakeably loyal fans who called for encores when record execs wouldn't even return manager Ray Danniels' phone calls. And Rush has been returning that compliment along the way by giving them their heavy metal dollar's worth in volume, virtuosity, and visuals, a gesture marked by the recent release of their first three albums-Rush, Fly By Night, and Caress Of Steel-as a low-priced retrospective package called Archives (Mercury).

Diminutive Lee, who fronts the band with a high-pitched screech of a singing voice, expresses little surprise at the thought of stampeding success. "People invariably ask us why Rush is happening in the midst of all this talk about punk rock. And I tell them it's because we're bringing the rock audience something they desperately want to hear-good, loud entertaining rock & roll."

Disc jockey Donna Halper first introduced Rush to the American radio audience five years ago over Cleveland's WMMS-FM. "Nobody took Rush seriously except the people," she says. "Rush never tried to be hip. They were filling a void, proving that straight-ahead rock & roll could feel good. One of the happiest moments of my life was seeing Rush at the Agora in Cleveland, to see the sight of so many kids-young, old, black, and white-all united by the simple spirit of rock & roll."

That communal spirit generated by Rush in stage standards like "Finding My Way" and the lengthy opus "2112" trades on the simple timeworn formula common to most bands descendant from the late 60's axis of Cream, Hendrix, and Zeppelin-a well-amplified succession of power chords dripping with distortion, fortified by pyrotechnical displays of solo electric guitar and relentless rhythmic drive from the bass and drum sectors. Although Geddy admits the group is riding high on what he calls "the second wave of heavy metal," he talks in the same breath of a new direction set somewhere between Led Zeppelin and Yes.

But where Rush strike the responsive note is in their unwillingness to compromise with record company interests for the sake of a sale. Outbackers in Rapid City. Iowa [sic] get the same pulverizing two-hour show as the big city sophisticates in New York and Los Angeles. This band puts out and the kids with the bucks never forget a favor. "We don't play down to our audiences. Our success is built on them. They are friends who helped us out when we needed it."

In 1973, Rush needed that kind of help. Canadian labels had already passed on the band one by one despite manager Danniels' sales pitch, convinced there was no market north of Detroit for such unpretentiously loud aggro-rock. So Danniels and company conspired to form their own label (Moon Records) and release Rush, a hastily recorded compendium of after-hours sessions that, through concentrated airplay on WMMS, eventually broke Rush in America.

Lee looks back at Rush with pride, "especially when I think of the conditions under which the album was made, two weeks of sessions after the gigs, recording until something like eight in the morning."

Their first, eagerly anticipated venture into America's rock & roll arena was almost scuttled before it began. As Geddy tells it, "the album was out and we were touring on that album, if you could call it that. We were actually playing Ontario's better bars. Then, just as we were set to re-lease the album in the States and do a tour with Uriah Heep, our original drummer John Rutsey decided that his heart really wasn't in it and quit. Fortunately, we found Neil Peart a few days later, auditioned him, and hit the road like nothing happened."

The five Rush albums recorded since the elegantly mustachioed Peart signed on as drummer and lyricist document the gradual shift to long conceptual works of artier rock like 2112 and parts of A Farewell to Kings, more typical of a Genesis or a Yes but the basic energy still intact. Caress of Steel was Rush's first such effort at a side-long story-line ("The Fountain of Lamneth") and Lee remains decidedly peeved at the poor sales and negative reaction it met on initial release.

"Caress of Steel was a big experiment for us and we were very much in love with it when we finished up. But again, the forces that be, the people who promote our music, didn't believe in that album. They sold it short and I think the inclusion of that album in Archives is the strongest reason for this collection to be released. We want to give Caress another chance."

For manager Ray Danniels, Archives is just one more example of the band's empathy with its fans, as he will draw a parallel only of popularity between Rush and a superior example of sophisticated marketing like Kiss. Rush is "a bargain to the consumer," justifying ticket and album prices with professionally staged shows and a high standard of recording.

Yet to Lee, Archives is "nothing but the music. There are no Rush army stickers; you're not joining anything. It's just a chance for more people to hear what Rush was doing in the days before 2112 and A Farewell To Kings but who can't afford three individual records."