Bucking the trends, Rush rides the crest of 'Permanent Waves'

By Lynn Van Matre, Chicago Tribune, March 30, 1980

"It wouldn't seem that the times are right for our music, no," acknowledged drummer Neil Peart of Rush, the low-profile, high-decibel Canadian rock trio whose latest album recently moved into the headier regions of the best-seller charts. "But then" Peart added, "you'd think that a band like Pink Floyd would be too obscure for the times, too, and look at them -- they're at the top of the charts."

On a 1980 music scene long on short, pithy pop tunes, Rush turns out mostly lengthy, quasi-mystical or philosophical songs on such topics as "Free Will," "The Spirit of Radio," and "Natural Science," the last a three-part affair about "art as expression, not as market campaigns." Past albums have attempted science-fiction rock opera and reflected songwriter Peart's interest in the literary works of Ayn Rand; before that, the band carried on its pounding power trio approach long after it ceased to be fashionable.

Rush would rate high on very few "bands of the '80s" lists, it would seem; its sound is neither fashionably spare nor couched in the catchy hooks that capture the ears of radio programmers. But while there's little doubt that it's the newer wave of bands that snares the lion's share of attention these days -- at least among the media -- the fact is, in many cases it's the bands considered by some of the more intolerantly trend-conscious to be outdated "dinosaurs" that are coming out the big winners.

Pink Floyd's marvelously lush and spacey sound, born in the late '60s and served up again and again by the band throughout the '70s, may indeed be anachronistic; but the magic still works. The band's newest release, "The Wall," a double-record concept album espousing the Floyd's oft-repeated theme of rock star as bitter victim, is currently the best-selling album in America and has been for some weeks. And right now, three notches below it, in fourth place, ranks Rush, enjoying their greatest commercial success in their half-dozen years together -- partly because of the airplay accorded "The Spirit of Radio," a single from the album, and partly, Peart would like to believe, "because, regardless of whether we fit in with today's trends in music or not, the vitality is still very strong.

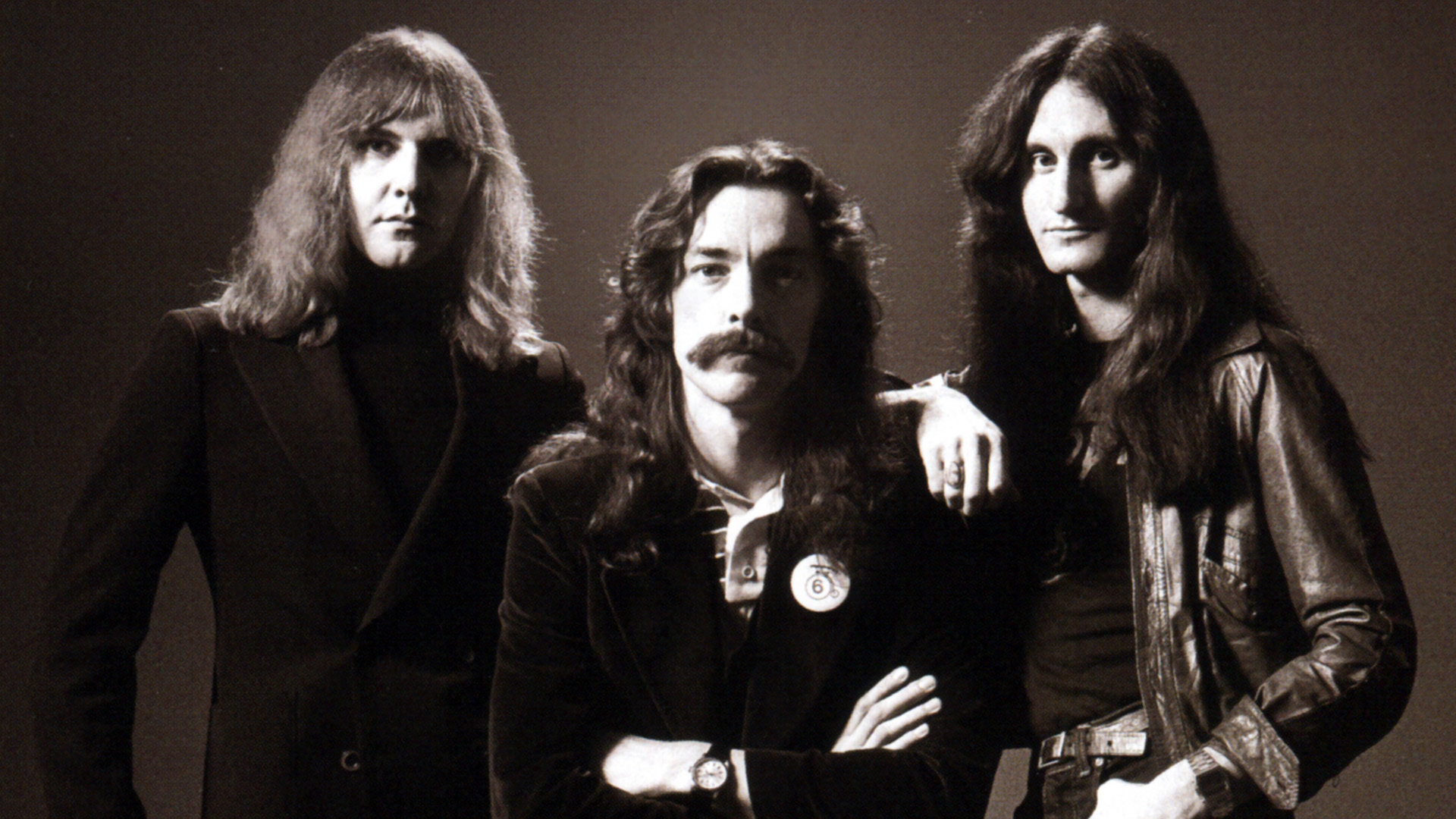

"And if you've got that vitality, I don't think the stylistic form of music matters," continued Peart, who will appear in concert with Rush vocalist and bass man Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson Thursday through next Sunday at the International Amphitheatre. "It doesn't make any difference whether you're doing white reggae or the resurrected '50s rock that most new wave music is made up of, or an ongoing thing like we represent, a permanent wave that isn't affected by styles."

Given Peart's reasoning, the band's current album is called, appropriately enough, "Permanent Waves." The name is, indeed, a poke at the new wave scene, "but not necessarily the bands themselves," Peart added. "There are many new wave groups we enjoy and respect, like Talking Heads and Elvis Costello and Joe Jackson. Really, the joke was aimed more at the press, especially the English rock press that is inclined to write off any band that was around last week and go for whatever's happening *this* week."

In the United States, Rush's reputation is largely that of a band written off by the rock press, a group that can garner respectable crowds of faithful followers but few favorable reviews ("Boasts a vocalist who sounds like a cross between Donald Duck and Robert Plant... the power boogie band for the 16 Magazine graduating class," sneered a review of Rush's record output in "The Rolling Stone Record Guide"). Peart professed puzzlement with that particular belief about the band.

"It's true, most people have the impression that we get only bad press," he said. "We do get bad reviews, but we get good ones, too. I have scrapbooks full of wonderful ones at home. But people do tend to think the press always dumps on us. I don't know why. As for interviews, we've always done a certain amount of those, too, and I like doing them, though it's never been a thing that we've made any sacrifices for. We've just never forced ourselves to be that strongly public relations-oriented. We spend most of our time on the road, playing in front of people, and we have a direct one-to-one relationship with people that way. We play our music for people, and they like it and buy our records. To me, that's the only thing that really works."

The rule in rock is that most bands tour to promote the sales of their albums and look forward tot he day when they can take more time off the road; Rush, Peart insisted, is one of the exceptions.

"To me, the work has to be seen as the end product," he explained. "I'm not working toward some goal of success. What I'm doing now is what I've always wanted to do. We've been at it for six years now, and I still like the work part. I get fed up with being on the road, but it has nothing to do with the performing. It has to do with the unnecessary garbage that happens in the other 22 hours of the day. When it comes down to those two hours that we stand onstage and play, I still enjoy them a lot."

Peart's interest in music dates back to his teen-age years; growing up in a small town near Toronto, he was initially excited by the Who, then moved on to such late-'60s acts as Cream, Led Zeppelin, Jeff Beck, and Jimi Hendrix.

"There was so much anger expressed during that period, and so much sincerity," recalled Peart, who dropped out of school at 17 to try to make it as a musician. "That was what I responded to, that feeling that there was something genuine being expressed by people like Peter Townsend. When he wrote a song, he knew how to express frustration and desire. And I think that a lot of the values and standards that we have in Rush are the same as the values that people stood for in the late '60s -- being true to the idea that, when you write a song, you don't worry about whether it's suitable for airplay or commercial enough.

"A lot of bands buckle under to those kinds of pressures. The record company tells them to make their next album more commercial or they won't put it out, and the bands do, because it's like if they don't, it's the end. They don't have enough faith in their work to stand up to that rap. I would rather just say goodbye at that point. I can do other things. I've worked in stores and done odd jobs before, and I could do it again.

"We've had plenty of people in the music business tell us to make our songs shorter and more commercial," he continued. "Those people aren't thinking in terms of a long-term career for us; we are. We want to do this for a good number of years, until we decide it's time to give it up. But for most record companies, the ideal is a band that makes it fast. An example with our record company (Mercury Records) would be Bachman Turner Overdrive. They lasted about two years, sold millions of records, then faded out. They were a quick investment, and the company didn't have to spend much money making them successful. For us, it took four albums before we started to break even, and record companies aren't interested in that.

"Now we're at the point where we can say 'Shut up, it's none of your business' to people who would try to tell us how to work," Peart said. "For a long time, though, we had to fight like hell."

While their recent commercial successes may have solved some problems, the band could do without at least one aspect of Rush's higher profile.

"We've noticed on this tour that there are a lot more weirdoes coming out of the woodwork," mused Peart, a family man who likes his privacy. "We could start a 'Flake of the Week' club. We get a lot of guy sending us pictures of themselves and telling us they want to 'help us out' -- they don't want to *take over*, they just want to 'do us a favor' by singing backup and doing some original dance routines. And all kinds of people send us letters saying that they have a plan to save the world and all they need is our help. Or they come up to us and say they've read all our lyrics and know exactly what we're saying and they're the only ones in the world that do. People extract amazing interpretations out of things. Someone told me one of my songs was about me going to search for God and finding Him. Yeah, right. Sure.

"There's a good portion of our audience, just like any other group of people, that we simply have no point of relationship with, and you just have to accept that," he continued. "But then there's the ideal fan, the person who appreciates every move we make and knows if we make a mistake and acts as kind of a built-in judge factor. Those are the people we write our songs for."