Rush Gains Fans In Hard Times

By Keith Morse, Milwaukee Sentinel, February 27, 1981, transcribed by pwrwindows

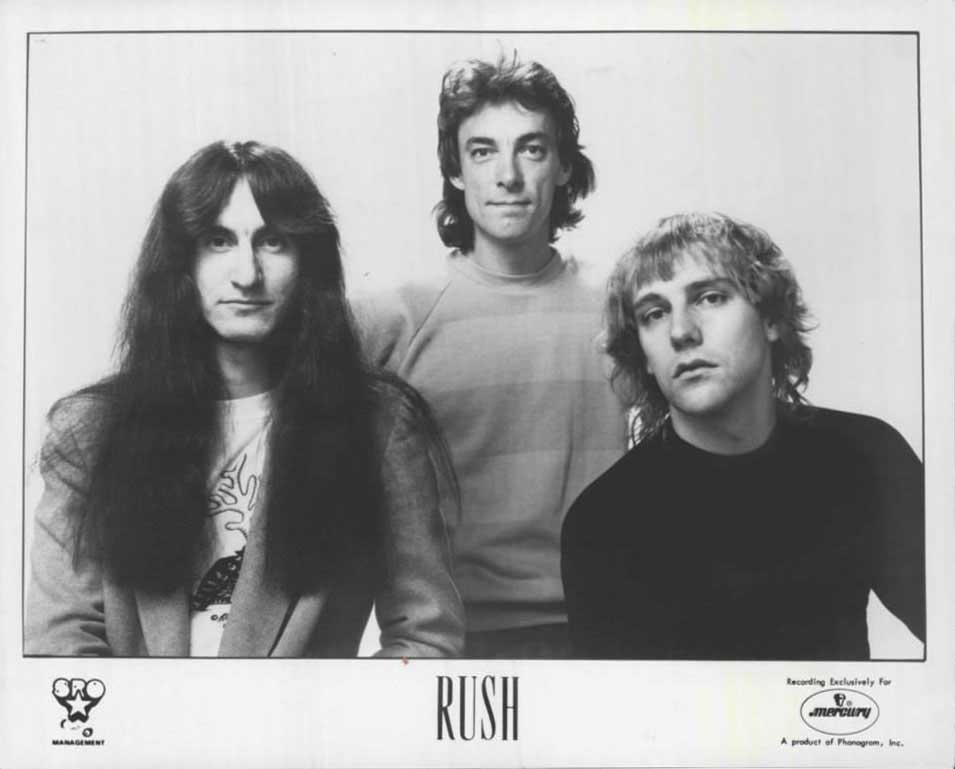

IN 1980, A YEAR that saw few rock bands do well on the road, the Canadian trio Rush established themselves as a major concert attraction.

In Milwaukee, they sold out two shows at the Auditorium and came close to filling it a third time. In Chicago, they sold out four shows. Elsewhere, they met similar success.

Rush will appear in Milwaukee Monday night at the Arena.

In spite of last year's decline in overall concert attendance, "we noticed all our fans were still there," said member Geddy Lee. "Obviously, we were doing something right."

What Rush has been doing, especially since their albums "2112" and "Farewell to Kings," released in 1976 and 1977, is mix progressive rock with the heavy-metal sound.

"A long time ago, we decided that was the place we'd like to be," Lee said. He added that the band liked bridging hard rock with the sound of bands like Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Yes and Genesis - bands that are now either defunct, hurt by personnel losses or suffer a less adventurous attitude.

"We wanted to combine their techniques. That's what our original goal was," Lee said. "I think we've achieved that."

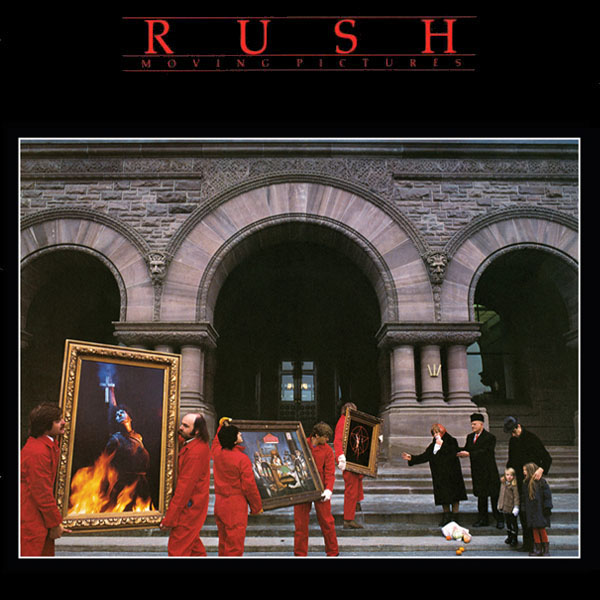

In their new album, Moving Pictures, there is evidence to back up that statement, Lee believed.

"There's a heavier emphasis on melodic content in this album," Lee said. "We tried to ease up on the shifts in rhythm. We really concentrated on the rhythmic feel - sticking to one rhythm and getting a groove rather than switching back and forth."

In the past, Lee said, the band relied on meter changes - almost as a way to divert attention from weak melodies.

Lee called this album "an exercise in trying to do one rhythm and keeping it interesting."

Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and percussionist Neil Peart probably have little trouble keeping interested or busy during concerts or recording.

Originally, Lee was strictly the bassist and vocalist for the band. As their sound matured, he began experimenting with synthesizers - using keyboards first, then adding foot pedals when he ran out of hands.

Lifeson also has an array of pedals at his toe-tips. Peart's stage drum kit and collection of percussion instruments could outfit a high school band.

Many bands use innumerable overdubs, studio musicians, tape loops and other devices in the studio and then leave it all to the audience's imagination in concert. Rush records few songs that cannot be played live and intact - something that would appear to stymie their arrangements.

"Obviously you can't do everything. There are some limitations, but we've never found it a deterrent," Lee said.

"We used 'Witch Hunt' as an opportunity to go wild in the studio with a song that we can't play live," he added.

Would Rush ever add a member - a keyboard player, for instance?

"There may come a point," Lee said, "but I don't see that. It's worked so far. If there comes a time when we feel it would do us more good than harm, we'd do it.

"But we'd have to find someone who could work with us. It's very difficult to do that. When Something works, you stay with it."

Particularly impressive about Moving Pictures is the sound quality - made possible by digital mastering and other quality-control measures.

"I was very impressed with the sound," Lee said.

"We used to hear, 'Why would a band like Rush use it? They have such a dirty sound.' The fact is, you get a cleaner reproduction of our dirty sound - it's more accurate. It cleans up some of the things that weren't supposed to sound dirty, too.

"We did analog mixes at the same time and compared them with the digital," Lee said. "On most tunes, the difference was enormous. You get a cleaner high end and a tighter bass, which I especially appreciate as a bassist."

Lee said the group "demanded" - and got - virgin (unrecycled) vinyl on their own label in Canada. In the United States, they "asked" - and didn't get it. "We were very selective about pressings, Lee added. "Our producer, Terry Brown, got very involved in the quality-control aspect.

"We'd go to such great lengths in the studio to get the right sound, we figured we might as well follow the rest of the process," Lee said.

Lee said a second live album may be out in the fall. The group had intended to release a live album now, but the plans were pushed back when they began making Moving Pictures. The band recorded some shows in London last summer and will do more taping on their present tour.

Moving Pictures Keeps Rush Moving

By Lennox Samuels

Last year, Journey described itself - a tad prematurely - as being as "big as Pink Floyd." Currently, REO Speedwagon has the No. 1 album in the country. These developments underscore the burgeoning popularity of bands than in the past had no more than a cult following. Another example is RUSH.

Only a few months ago, this Canadian trio was roundly dismissed as an act that liked to wallow in abstruse, portentous techno-rock. As critics sneered, however, the kids flocked to the band's live shows. While I'm still not prepared to genuflect before the Rush shrine, I'll maintain that the band's new album is nicely accessible and it's lyrical and melodic content frequently interesting.

Moving Pictures (Mercury), is not wholly devoid of bombast but neither is it as other-worldy as some of this act's earlier music. The disparate ideas begin right away on Side 1 with "Torn Sawyer," an updating of the white-picket-fence hero in which the lyrics laud independence of spirit and the melody reflects the band's synthesizer orientation, with a nod to jazz. "Red Barchetta" is less a philosophic piece than a evocation of pastoral scenes. "YYZ" an finely woven instrumental, points to the individual talents of guitarist Alex Lifeson, bassist Geddy Lee and percussionist Neil Peart, the model of many young drummers.

The band devotes a good chunk of Side 2 to "The Camera Eye," a reminder, as it were, that Rush, despite its often heavy-handed brand of rock 'n' roll, is one of the more literate bands around. Despite occasionally flaccid stretches, this cut is, surprisingly, very attractive for a long number, with relatively intelligent lyrics and intricate melodies.