Neil Peart & Rush Go Public On 'Moving Pictures'

The Canadian Trio's Last Lp Actually Received Some Positive Reviews; Their New One, Moving Pictures, Should Please Press And People Alike

By Don Myers, Circus, March 31, 1981, transcribed by John Patuto

Rush drummer Neil Peart was just back from a sailing vacation in the Caribbean. The cruise marked the fulfillment of a longtime dream of Peart's. "I've always had a fascination for the sea in a distant way, through books," Peart explains excitedly. "I got into the whole romance of sailing and being on the open seas. I had no idea of how good it would feel; there's so much freedom in it." It's not hard to visualize Peart's long, brown hair blowing in the sea breezes as he moves in the reflections of sky and water, and uses his hands, which so dynamically propel Rush's sound, to trim sails and haul on the bowline.

Canadian Peart loves both weather extremes, for he's also developed an interest in cross-country skiing. He and the other members of Rush - blond lead guitarist Alex Lifeson and witty bassist Geddy Lee - also share a lifelong interest in ice hockey. (Montreal Canadian's star winger Steve Shutt, whose team plays the same Ontario arenas as Rush, gave the band a lifetime supply of hockey sticks last year.)

Peart, Lee and Lifeson have been playing hard-boiled rock & roll together for seven years now. Although it's true that the band has been getting better reviews since Permanent Waves became such a big success for them and Mercury Records, in the past they were often savagely ripped in the press. And the most vicious blows have been aimed straight at the mysterious, romantic Rush figurehead, drummer Neil Peart.

Early in 1977, Georgia Christgau had a piece published in Circus Magazine that was supposed to be a review of Rush's breakthrough live album, All the World's a Stage. It appeared to be no more than violent personal attack on Neil Peart. Christgau's most brutal cut took the form of a quick summation of Peart's lyrics and personality. "Today they promote philosophy, too, detailed with self-inflated thoughts one gets from too many nights in front of a throng: 'I'm gonna get my money out of you fuckers if it takes two more years,' is one paraphrase," wrote Christgau.

Peart's response to this bit is amazingly restrained, and his gentle manner is a stark contrast to it. "It was a personal attack, which was what freaked me," he says in a tone of wonder. "It was painful at the time, because it was so long ago that I hadn't had much exposure to that kind of thing and I wasn't 'thick-skinned' about it. It went right in."

Peart is the most visible target for the critics' barbs because he writes Rush's lyrics, and the lyrics are the prime source for the claims that the band wraps itself in an air of intellectuality and mystery. These same, Ayn Rand-based lyrics also give rise to accusations that Rush are neo-fascists and right wing extremists. Peart, who believes that people have the right to think and do as they please without the burdens of heavy restrictions and repression, replies to the charges of neo-fascism vehemently. "I hate that more than anything. I can't bear to be protected from myself."

Peart appears to be a private person caught in a public business. The fact that he doesn't want to talk about what color socks he wears or who he's sleeping with seems to grate on gossip-hungry publicity mavens. It may be that the media mill has created the cloak of mystery that shrouds him and the others, and causes the fans to be awestruck. Peart strikes out at this syndrome when he describes "Limelight," one of the cuts on the new album, as an attempt by Rush to blow apart "the perpetuation of myths in the entertainment business." Peart wants Rush's audience to understand that the three guys in the band are just regular people, not "demi-gods or supernatural beings."

Peart adds that the band has worked very hard "not to become estranged and insulated from its audience without projecting "some false, country boy image."

How Rush managed to come in with a Top 10 LP (Permanent Waves) is still a mystery to many. Jim Sotet, Polygram's Executive for National Album Promotion, thinks he has an answer. "Rush is successful because they're loyal to their rock & roll fans," he exclaims. "They've never been swayed by the trendy publicity types who keep cynically foisting off new fads on the artists and the fans."

Another point demands consideration: Young people are spending a great deal of time with visual images because of television. They have also become accustomed to being excited by giant cinematic extravaganzas like Star Wars. Rush has all the latest digital sound equipment. Rush's record sales didn't start to take off until they began to play the large halls like the Checkerdome in St. Louis, Chicago Stadium and Detroit's Cobo Arena. Explains one New York rock writer: "Their album sales jumped when so many more people started seeing their shows and getting excited enough to buy the records. Their songwriting also took a turn for the better in 1977, when they made A Farewell to Kings."

In the songwriting department, the lanky, often mustachioed Peart gets many of his ideas for stories and lyrics while he's on the road. "I keep a notebook in which I record different impressions, story ideas and word combinations," he explains. Peart also has a collection of possible song titles that he hopes will inspire him when he's home with a quiet place to work in. He gathers data on the road, but does most of the actual writing at his farmhouse near Toronto. All the members of Rush work closely together on developing their words and music while they are on the road. They even took some of the material for their new LP, Moving Pictures, on a short tour last year so that it would be really tight by the time they went into the studio.

Moving Pictures is something of a departure for Rush. It's a collection of more compact pieces than those featured on 2112 and all the early albums, with an emphasis on musical and vocal melody and a heightened rhythmic flow. "It's the first album that we've really allowed to breathe as far as rhythm goes," says Geddy Lee. "We lock into a groove or a feel, and we'll stay there."

The effects of the spare form of the music are evident throughout the record. Most of the cuts are in the four-minute range. Lee's vocals are not excessively high - an important consideration in fighting for radio airtime - and he seems to enjoy singing more in the lower register. The music is much less jumpy and much more distinct; this change is clearest in the final cut, "Vital Signs." The song contains elements of the uncluttered hard rock music of current performers such as Max Webster. Lifeson describes his work on the upbeat tune this way: "It's the first time I've done something like that; I almost always double-track my guitars for a nice, fat sound. This time we went for a particular sound that would be very individual. It's a very clean, bright sound."

The album's concise forms have also affected Peart's lyrics and story lines. These are much more finely crafted than on the band's previous eight discs. Peart drives home the point that the discipline of writing verse has made him see that he went through a long period of being "gothic and ornamental about things." Like that of the English novelists (Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy) he read when younger, that style is beginning to seem excessive to him now. (By contrast, a recent Peart favorite was Your Erroneous Zones.)

"I started to see how all the things I created could be done with far fewer words," says Peart. This new direction is most evident on "Vital Signs," "Witch Hunt" and "Red Barchetta," a long, futuristic story that's kept to a modest, six-minute form.

"Witch Hunt," because of its heavy keyboard orchestration, is the only new song that won't be a part of the next Rush tour, which began in late February and is to continue to the summer.

"I love the highs and lows that go along with being on tour," says Neil, who claims that the experience of being away and traveling for such long periods amplifies all the feelings and ideas he has. Rush usually tour with bands whose music they like themselves. "To me," concludes Peart, "cynicism is one of the great enemies."

The kids love it, the critics love to hate it

by Philip Bashe

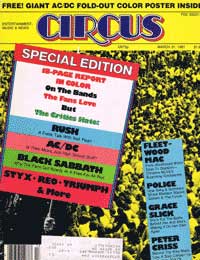

Rush is one, but Fleetwood Mac isn't. Jackson Browne doesn't even come close. AC/DC is, and so are Black Sabbath, Styx, REO Speedwagon and Triumph. They are People's Bands, and they play the People's Rock, the music whose fans elect it to the top of the charts as regularly, and as vehemently, as the rock press strikes it down.

It's become a sort of de facto rule of rock: Whatever the people love, the critics hate, and vice versa. Writers' annual lists of the best albums usually include those discs that settled to the bottom of the Hot 100, assuming they even made it on the charts at all; not surprisingly, most rock magazine readers will probably never have heard of - let alone listened to - half the picks. And rock scribes will never understand what could possibly attract rock fans to the bands featured in this special section of Circus Magazine.

That these groups sell scads of records obviously means that these writers are wrong, right? In fairness, no, since there is no right or wrong opinion. And reviews are just that - opinions and impressions of the writer. Despite what they teach in journalism classes, objectivity is the writer's pipedream. "All critics are subjective," asserts critic John Rockwell of the New York Times. Of course, once that opinion is presented as gospel (that is, printed) truth, a rock & roller who's just had his latest LP demolished in print can easily take umbrage at the very idea of "fairness."

The Great Divide between what is critically correct and what is commercially popular does suggest that the press's influence has been exaggerated (although you do have the case of Eric Clapton, who decided to curdle Cream, busting up the band after reading an especially nasty review by Rolling Stone's Jann Wenner). Just how seriously readers regard record reviews is unclear ("I have no way of knowing; some people get upset by what Ann Landers says, some don't care at all," comments Wayne Robins of Long Island's Newsday), but the reason such critiques bother the artists is obvious.

"I don't mind bad reviews," says Kansas drummer Phil Ehart, "because Kansas is large enough and successful enough that they don't really affect us." What does disturb Ehart, whose group has been particularly targeted by the rock press, "is that lots of magazines and newspapers have music critics who probably couldn't carry a tune in a bucket; their qualifications are sometimes lacking."

What probably riles musicians most is that the columnists always get in the last word(s). Some artists attempt to rectify that by writing letters in rebuttal to what they consider unfair criticism. Some, like Neil Peart of Rush, choose the gentlemanly way. Peart once answered a negative review in Circus Magazine with an intelligent, detailed letter that patiently took the writer's position apart line by line. Others, like the Jefferson Starship's Paul Kantner, are more direct. A Kantner reply to a less than kind Rolling Stone review stated simply: "Fu ... uuck you."

Still others take to their soapbox - the stage - to get their point across. Presumably, that's what Billy Joel had in mind when he ranted against the Los Angeles Herald Examiner's Ken Tucker for a review in which Tucker called Joel "the Great Spoiled Brat of Rock." The piano man elicited cheers when he yelled out "Fuck you, Ken Tucker!" and (just like a spoiled brat) shredded a copy of the offending review. "Yeah, he got that part right," says Tucker, who had attended the previous night's performance, and found out about Billy's tantrum through a series of phone calls that continued into the next day.

But Joel misconstrued something else Tucker had typed (just as critics frequently misinterpret an artist's work?), which was the real cause of his wrath. "He got it all wrong," contends Tucker. "He obviously didn't read it."

So does the dichotomy exist? Everyone has his own theories, including David Lee Roth of Van Halen, who expands upon his earlier pronouncement that rock critics love the nerdy-looking Elvis Costello "because they look like Elvis Costello." Says Roth now: "The real truth is that many of the critics are getting to be thirty years old and older, and now have kids of their own. And it scares the hell out of them to think their kids could be anything remotely like David Lee Roth, because by this time a lot of their kids are starting to look like David Lee Roth."

To which Mitchell Schneider, who writes for BAM and New York Rocker (and looks nothing like the defamed Mr. Costello) responds: "If Mr. Roth is so in love with himself, why doesn't he go all the way in self-flattery, and simply market the David Lee Roth Doll. It goes without saying that when you pull the string, absolutely nothing happens."

And the battle rages on.

With 'Moving Pictures,' Canadian power trio Rush finally combine

the mystery of Led Zep with the fury of Yes.

Continuing the progress shown on Permanent Waves, Rush's last record, this eighth Rush studio LP features fuller melodies and less gratuitous riffing than their more chaotic early albums. Yet it still leaves some of the band's major problems unresolved.

At its best, Rush's music attempts two styles: the eerie, dark-chorded sound of Led Zeppelin and the charging fury of Yes's rocking rhythm section. The two tracks that kick off Moving Pictures, "Tom Sawyer" and "Red Barchetta," both have the sort of mysterious synthesizer, guitar and bass bits Led Zeppelin raised to the level of gothic horror. Guitarist Alex Lifeson, while no Jimmy Page, at least has a strong sense of humor. The problem is with singer Geddy Lee, whose over-articulated delivery often reduces potential mood pieces to mere uppity heavy metal. Lee's exaggerated singing style also draws too much attention to the homily-filled lyrics on such numbers as "Witch Hunt."

It is actually the Yes style that Rush do best with. Geddy Lee's bass, like Chris Squire's, is as prominent as the guitar, bouncing off the other instruments to give a sense of free-form excitement and unpredictability. It is particularly fun on Side One, where you're tempted to turn down the treble completely and let the bass knock around for the full 20 minutes. Side Two is not as well structured. The 11-minute "The Camera Eye" spends an inordinate amount of time on some dull progressions. But the side's closer, "Vital Signs," has at least one surprise - a reggae steel guitar. Interestingly, Side One has a song, "Limelight," that almost approaches (my God!) pop, easing somewhat the squeaky edge of Lee's abrasive voice.

Rush are refining their music, which is a good sign. But right now there are still too many self-conscious chord progressions, vocal mannerisms and lyrical problems to make Moving Pictures anything more than intermittently enjoyable.