Rush

By Greg Quill, Canadian Musician, December 1981, transcribed by John Patuto

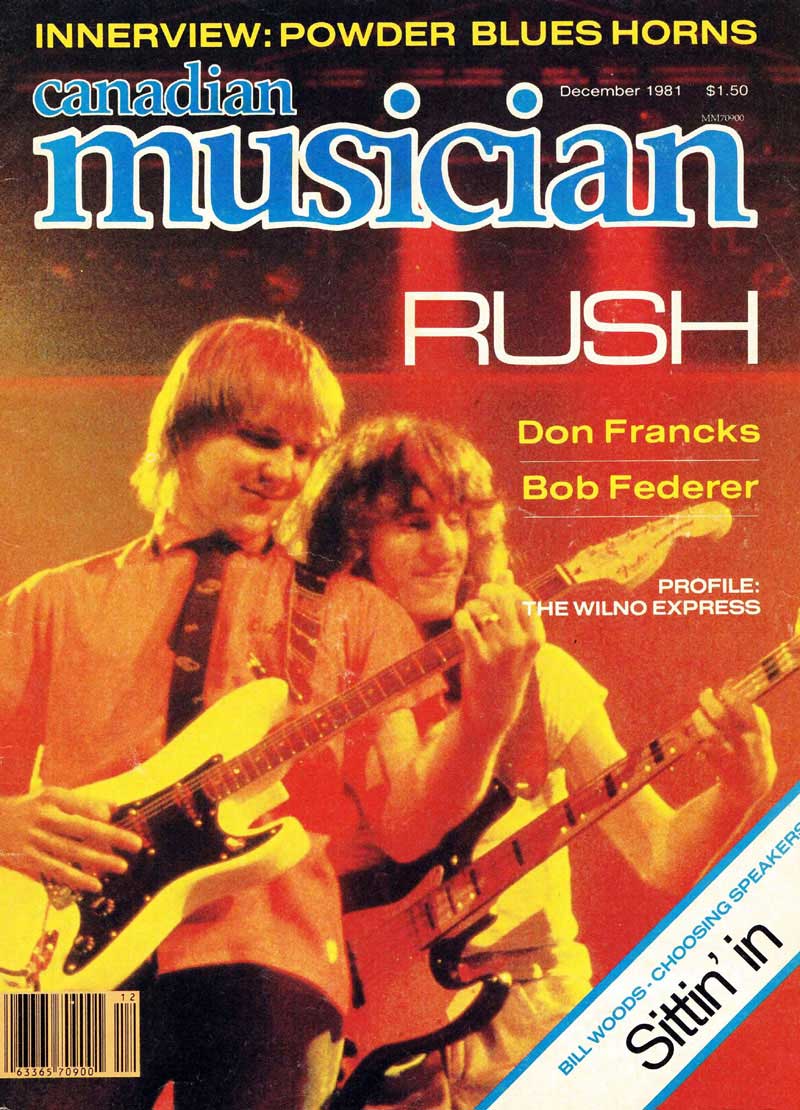

Alex Lifeson, Rush's indisputably gorgeous guitarist, and perhaps the band's single iconoclast, was reluctantly trying to come to terms with what appears to be a new tidal wave of Rush consciousness. In the summer sunshine, temporarily exhausted from a couple of hours of strenuous volleyball with bassist/singer Geddy Lee - their only real and regulated exercise during a month of mixing sessions. They'd booked at Le Studio in Quebec's Morin Heights - Lifeson and Lee were reflecting on the successes and excesses of recent months.

This past summer, expecting a respectable reception to their Moving Pictures tour, the Toronto-based band encountered sold-out arena after sold-out arena throughout the United States and Canada. Ticket sales had been so good, in fact, that in many American cities where Rush were already well established - Seattle, Chicago, Los Angeles and others - they were compelled to satisfy a drastically increased and unexpected demand by delivering multiple performances - as many as four shows in one venue.

That's gratifying, of course, but Alex is a little hesitant about offering projections as to where it all might end. The band had, after all, intended to scale down its touring schedule. After seven hard years, they'd figured they'd reached a comfortable plateau. This summer convinced them that Rush's popularity is certainly undiminished; it's not even stable. Sales of Moving Pictures, the unscheduled, unexpected studio album that simply called itself into existence more or less out of thin air, interrupting well-laid and very expensive plans to release a live collage culled from mostly European performances recorded during 1980, have doubled those of previous, groundbreaking Permanent Waves - itself something of a risky proposition, representing a determined departure from the band's hitherto bone-shattering heavy metal efforts and initiating a textured, melodic, even thoughtful style. Moving Pictures took that new and mature inclination one step further, another step away from what Rush had long staked out as their own narrow territory, and into less familiar, more challenging regions.

To their unanimous dismay, their fans, to a man, came with them, and brought some new friends - in droves!

"Ninety-five percent of all shows on this tour were sold out," Alex said, obviously still a little stunned by the immense figures, "which was way above what we'd expected. It means we came off the road with a little bit of money."

Understatement is usually the metier of the ever diplomatic Geddy Lee, but Lifeson this time admitted there was enough to clear not only their mammoth lighting, sound, staging and transportation expenses, but additionally to pay crew wages and retainers for a full year until August 1982, when Rush's rigid schedule prescribes their next major North American tour. Considering most bands of megabuck dimensions expect to lose money on national tours that are considered necessary for the promotion of monster album sales, the real source of income, according to traditional values, Alex, Geddy and drummer Neil Peart are way ahead of the game. Their 1981 tour turned a profit in itself, and Moving Pictures is still sitting comfortably in the U.S. Top 20, a full six months after its release. Is it any wonder Lifeson worries about things getting too easy?

"When shows are sold out," he added, "everything seems to run a lot more smoothly. Promoters try a little harder to please you, and that works through all the ranks. It makes it a lot more pleasant being on the road."

Currently preparing their second live album, as yet untitled, the trio, with producer Terry Brown, have been working painstakingly through more than 70 reels of multi-track tape. So many in fact, Brown couldn't fit them all in his car. They represent performances from British dates in 1980 through to the just completed summer shows in LA and Montreal. That's an agonizing number of critical listening hours, a task made a tad easier by some initial scrutiny in Toronto. Once particular performances have been selected, the four men will spend the remainder of the time mixing and editing - with little opportunity to experience much apart from the soft glow of studio lights and the monitors' magnificent roar. Like monks labouring over some intense religious devotion, they expect not to be disturbed by terrestrial events till a double album's worth of live work sits frothing on the mastering lathe.

In addition, a fifteen minute colour film of the band's recent show in Montreal is to be edited to coincide with the pre-Christmas release of the album, which Geddy explains, will feature material from A Farewell To Kings, Hemispheres, Permanent Waves, and Moving Pictures, plus a couple of older songs that are retained in the current repertoire - taken from dates in London, Scotland, Toronto, Montreal, Edmonton and other cities they played this summer.

"Basically, we're covering the period of studio material since the last live album," he continued. "There are some differences in feel from the studio versions, little things that improve the live performance. The rhythm section feels a little more natural, tempos are slightly changed and there's more intensity, more energy - a raw energy that only seems possible in live recordings."

Familiar with Rush's practice of recording only material it feels it can accurately reproduce on stage - "Witch Hunt", for example from Moving Pictures, is not included in the live repertoire even though its popularity would seem to demand at least an attempt. It was recorded with additional synthesizer parts the trio is physically incapable of manipulating in a live situation. I asked Geddy why the band feels it necessary to offer a live recording at all.

"A live album accomplishes several things. First, it buys us time and rests our brains," he replied. "And it gives our hardcore fans something they can ... well, treasure. Our motivation for releasing this particular record is to present an update of the band's sound. The last live album was done before we went through most of our textural and instrumental changes. We want everyone to know we're not just a power trio any more.

"And a live album has a certain historical value. I don't necessarily see the merit in playing live versions of recent studio hits on radio unless they offer something radically different, so I agree with those critics who complain about that - to a point. A good live recording shouldn't just duplicate the best elements of the studio version. We try to give a whole new feel, a new perspective to the material, and that's the most important thing in music."

In the interests of offering more eloquent music to an audience all three Rush members refer to with constant reverence; this band has continued to expand and experiment where groups twice their size and half as popular might have been content to adhere to a simple, proven schtick. Alex and Geddy agreed that their decision to expand instrumentally has brought them all closer together and broadened their musical ideas and capabilities. Rush's last two albums bear witness to a major stylistic and substantive rejuvenation within the band.

"I used to wonder how Geddy could play bass and sing," Alex laughed. "It's a lot like rubbing your stomach and patting your head at the same time. But now, especially listening to the live tapes, I'm even more amazed that he's playing all those instruments, and parts, and singing just like he does in the studio."

It's Geddy who has assumed most of the additional instrumental load since the power trio days, although Lifeson employs a virtual crateload of guitars on stage, embellished by a staggering range of outboard devices, and even Peart has augmented his palatial drum "cage" with more and more exotic percussive pieces and synthetic gadgetry. Rush sounds at times like two or three complete bands and half the Toronto Symphony.

Geddy's role has expanded from your basic vocalist/bass player to occasional rhythm guitarist and multi-keyboardist. Several intricate bass and synthesizer lines are accomplished by foot, while his hands are busy elsewhere.

"We added the pieces slowly over the last three or four years," Geddy explained. "I started out with simple bass pedals, then added a Mini-Moog, then something with a polyphonic capability, experimenting with horn and string sounds, till it became the monster it is today. Alex even plays a set of Taurus pedals now.

"I had never played a keyboard till then. The additions were always very natural though, piece by piece. I took my time getting to know each instrument before starting on something else. It takes a lot of concentration and practice. I still don't consider myself a keyboard player - maybe a synthesist."

Despite his obvious pleasure with his stacks of "all the latest toys", Lee still sees his primary function as a bassist, and that instrument is surprisingly free of surplus effects.

"I use a flange effect in a couple of places, but I leave that to Jon (Erikson, Rush's newly-acquired sound engineer, and the man responsible for redesigning the band's flying PA system and on-stage miking techniques). Otherwise, my bass is straight."

More understatement. Geddy uses a stereo Rickenbacker for most of his work, through VTW amplification and Ashly preamps, and two different speaker setups, one for each pickup.

"For the high-end pickup, I use 15" Thiel designed cabinets with EVM 15" speakers. The low-end pickup goes through a similar amplification system, then to Ampeg V4B cabinets with 15" J8L speakers. The amps are 750 B's, about 300 watts apiece, I think - but I don't use all of that, of course.

"The left-hand channel is pre-set for the Rickenbacker setup, but the right-hand channel of the stereo system is switchable to mono for a Fender Jazz bass I use on a couple of tunes. Its eq is preset through a separate pre-amp, so I can switch back and forth in about 30 seconds.

"The advantage is that I can set up the separate eq and have it all patched, so when I need that particular Fender bottom end and mid-range punch, it's just a matter of switching over to the other side of the amplifier, redirecting the signal to both sets of speakers."

Alex Lifeson's stage instruments are substantially more varied than Geddy's two basses. He uses no less than eight guitars during the course of a single show: a Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion; a Gibson ES355; two Fender Stratocasters, both fitted with humbucking pickups; a Gibson 1185 double neck (6 and 12 string); an Ovation Adamas acoustic guitar (with carbon graphite face); an Ovation Classic; and a Gibson ES345 as a back-up. All guitars are patched through a separate mixer and pre-amp, he said, and his equalization is reasonably constant from one instrument to the next, though a Maestro parametric filter on stage gives him infinite flexibility should he need it.

"It works like a parametric equalizer," he explained. " You can set the filter to any band width and any length of band width, so if you want to boost it around, say, a thousand cycles, you can boost it right at a thousand from a very narrow boost to a very wide boost. It's variable from zero to 15,000 cycles.

"I keep it more or less pre-set. I find what I lose with my effects, I can compensate for with the parametric. On occasion I have to re-eq it to the room. Very seldom though."

His outboard effects include a Roland Boss Chorus, a Mutron Octave Divider, an Electro-Harmonix Electric Mistress phaser, an MXR Distortion Plus unit, a Morely volume pedal and a Crybaby wah wah - as well as his Moog Taurus synthesizer pedals, proud he is at last to be rubbing his stomach and patting his head simultaneously.

Sometime after the release of the new album, Alex intimated the members of the band will likely splinter off for a while to pursue some individual projects. Geddy will probably look into some production work, the ever elusive Neil Peart will no doubt devote himself to specifically unmusical activities (Geddy suggested that Peart, an avid reader and exceptionally talented lyricist is interested in pursuing a literary career) and Alex said he'd like to produce a solo record.

"It's fairly tentative at the moment," Alex continued. "I have a studio at home and I've been putting some things together, but till I get the time to dig my teeth into it, I don't know how much of what I've been doing I'll keep. It's just something I'd like to try on my own. I think if I did something like that I'd put some variety into it, try a few instrumental things, maybe some vocals. It would be what you'd expect a solo guitarist's album to be."

His favourite guitarist is Alan Holsworth - "the choice of most guitarists I know" - though Alex admitted he rarely listens to radio either to keep tabs on his counterparts in other bands or to provide some contemporary reference for himself as a songwriter.

"No." He was emphatic. "I've always stayed away from radio comparisons. I know a lot of artists do that, and I can appreciate why they do it, but I never have. It's a lot more satisfying having achieved some degree of commercial success by doing it our own way.

"Besides, I always seem to be doing other things. I'd never get the chance to listen to radio even if I wanted to."

What occupies most of his spare time these days, apart from his wife and two children, whom, he confessed, he misses more each time he hits the road, is flying, a newly discovered passion and something he's managed to become sufficiently accomplished in, despite his seemingly endless commitment to the band. His instructor, "Vings", even managed to get in some lessons during this recent tour, on days off, days when Alex said there'd be little else to do but get bored or drink a lot. He even managed to get his American license from the FAA and is now working on improving his ratings.

When asked whether he was happy with the way Rush's following seemed to be growing with each album, Alex hesitated before answering in a not-too-convincing affirmative.

"I hesitated because there are other interests I have that I suppose I'd like to get into a little more - and I think I'm missing out on them sometimes. It's such a small thing. I hardly feel it's worth mentioning. And I guess, no matter who you are or what you do, there are always things you'd love to get around to that somehow you know you never will.

"It may sound strange, but I have this urge to go work with my brother-in-law sometime, putting up fences for a couple of weeks - or just take some time to get in some decent flying hours. I don't know - I don't spend much time worrying about it, but it's there, way off in the distance.

"As far as the band goes, I don't think our relationship will ever change, even if we didn't see each other for ten years. In fact, if it wasn't for this particular band, I wouldn't do all this. I wouldn't do it all over again..."