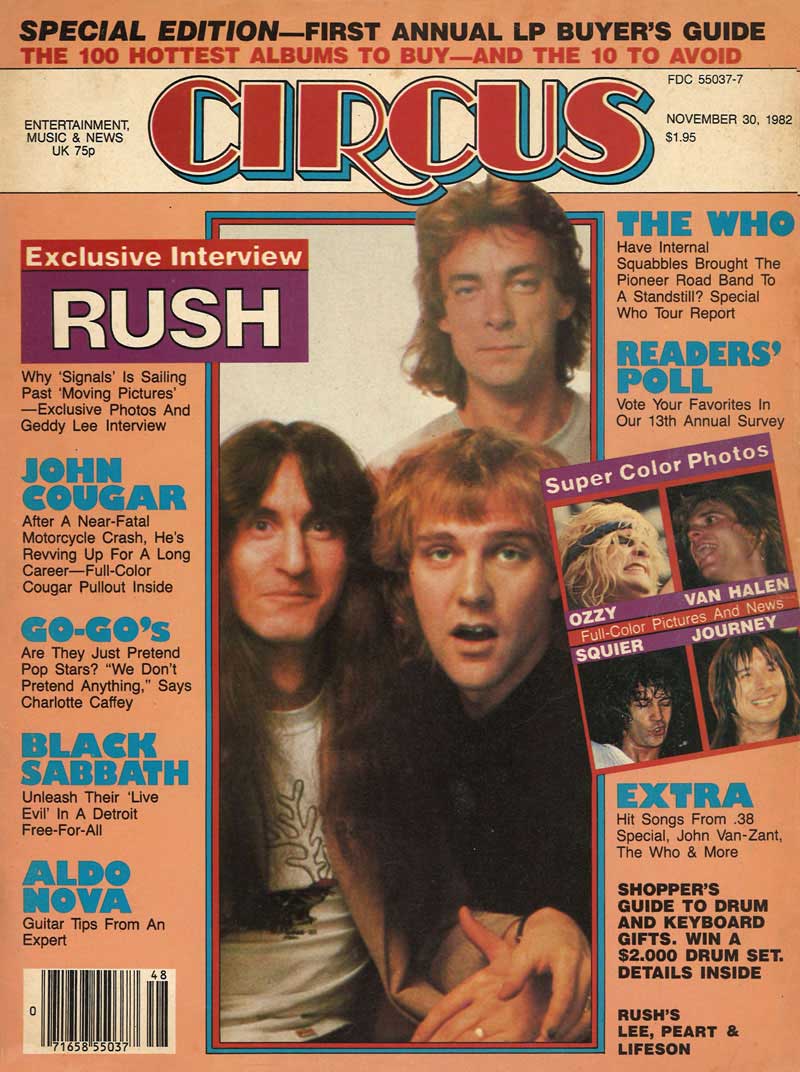

Rush's Simpler 'Signals'

By Philip Basche, Circus, November 30, 1982, transcribed by George Rogic

If there's one thing rock journalists dread more than watery drinks at press functions, it's facing the wrath of Rush fans disgruntled over a less than favorable review. Not only are they a vocal lot who will gladly spring for the postage in order to castigate the offending scribe, but they're unusually articulate. Basically intelligent fans for a basically intelligent band; it's a unique relationship.

Rush's use of rhythms that switch gears in midstream might put off less adventurous listeners whose pulses are locked into 4/4 time. And their lyrics, penned by drummer Neil Peart, encompass themes of individualism and the evils of technology, usually set in a sci-fi panorama; out of eight studio LP's, there's not a typical paean to sex, drugs and rock & roll in the bunch. And Rush fans thrive on it. If what the group does goes over their heads, it's only those of younger fans who stand under five feet tall. That Rush can address their audience on a discerning level - and have it understood - is something they're highly appreciative of.

"It's a nice aspect," says bassist Geddy Lee, "although of course you can't relate to everybody on that level; we're talking about a large cross-section of people. But we've always had a very simple approach to our music: We never play down to our audience. We try to appeal to what we consider to be the ideal fan - someone whose taste is closely aligned with ours."

Rush's last three LP's have gone Top 10, quite a feat for a band whose music is so atypical of most commercial successes. *Signals* (Mercury), their 10th album overall, should be their biggest yet. On this record, even moreso than on last year's *Moving Pictures* and 1980's *Permanent Waves*, the music's jagged edges have been softened and the rhythms are less frenzied. Synthesizers replace what normally would be solo space for guitarist Alex Lifeson, who enriches songs like "Losing It" and "Chemistry" with atmospheric sunbursts of color. Why the modification of sound? Lee credits some of the music the band has listened to during the past year, like one of Peart's favorite records, Ultravox's moody, layered *Vienna*.

It's also a case of artistic maturity. In Rush's early stages, Lee admits, "We were not very good technically. When you're a young musician your goal is simply to become better. There are some good ends, but sometimes you find yourself being complicated for the sake of complication, which doesn't always make for good music."

After completing their last concept LP, 1978's *Hemispheres*, Rush were at a point where they no longer felt compelled to prove their proficiency by uncoiling songs into lengthy epics. "We realized," said Lee, "that one element often lacking in our music was feel. And we're finding that working in a shorter framework, which we used to think was the easy way out, isn't really easy at all. It comes down to being confident in our musicianship."

That is what Rush fans care about the most: the music. According to Michael McLoughlin, a longtime Rush associate who oversees the band's merchandising and heads the 10,000-member Rush fan club, many of them are musicians. They admire singer Lee for his impossible high notes, Lifeson for his digital dexterity, and Peart for his stick flourishes. On stage, the group is tame by most standards: Lee stands virtually motionless behind the mike stand, moving his hands rapidly across his bass neck and pressing his foot pedals. Lifeson also doesn't move much, as he concentrates on meticulous solos and fills. And Peart is seen from the audience as a mere head bobbing up and down in a sea of cymbals and tom-toms. Acrobatics are kept to a minimum. But Rush fans allow them that; they understand how physically difficult performing much of the material is.

"They're pretty mature," McLoughlin says of the group's audience. "They're not interested in what Geddy's favorite color is or what kind of girls the group likes. There's no real sex symbol in the band, so it doesn't attract that sort of fan." Where live rock's appeal partly lies in the simple peddling of sex, Rush fans appreciate their heroes from the shoulders up.

But as they get bigger, cautions Lee, "there's more of an interest in the other, non-musical side of the band. The real dedicated fan wants to know everything about you." And that presents a problem. Lee and Lifeson are reserved men who cherish their privacy, and Peart is even more adamant about his dread of stardom. (Sample these lyrics from "Limelight": "Cast in this unlikely role/one must put up barriers to keep oneself intact.")

For Geddy Lee, it became such a struggle that he was forced to vacate Toronto for the outlying countryside. With his long dark hair and prominent nose, he's easily recognizable, and life became intolerable. "My home life was havoc; people wouldn't leave me alone, and I had no peace of mind. But since I've moved out to the country, I've been able to get a better perspective on it, and I deal with fame much better."

The majority of fans respect the group's wishes for privacy, says Lee, "but there's always a fringe which doesn't understand - and will never understand -that an artist's main responsibility is to perform well. And that's where it ends."

Lee is asked if he finds the basic relationship between fan and star unfair. The fan is usually allowed to be a voyeur into the celebrity's life, but it's rarely reciprocal. "I don't know," he says, mulling over the question before posting one of his own. "Where do the fans and artist really meet? Through music. Everything we do, all our emotions and things we want to say, we put into our music.

"And when we're in the concert hall together and we're playing and they're responding, and it's one of those nights where everything is going well, that should be communication enough."

Private as they are; Rush do attempt to make contact in other ways. The concert setting in the U.S. and Canada disturbs Lee because its immensity makes interaction difficult. "The whole system is geared to size: twenty thousand-seat halls, twenty thousand kids, sections being roped off. It's geared to keep the fan way from the guy in the band, and that's alienating. We always try to get around that."

One way is to sign autographs after the show, which Rush almost always do, and to answer fan mail. Because the volume of mail has escalated along with the band's popularity, that has become an almost impossible task.

Lyricist Peart especially gets inundated with mail, much of it from zealots who believe they've discovered the "message" behind his words, even though, as he's stressed many times, "We are not a message band."

"Some of it's pretty weird," says Lee, "religious connotations, messages from God; all these things we're supposed to be saying. 'Hello, sports fans, here's a message...'"

It can be unsettling at times. Peart once cracked that the group could start a "Flake of the Week Club" based on some of its mail - letters from guys who send in their pictures and offer to assist the band on its next album, or from those who have a plan to save the world and need Rush's help. On the other hand there are the other letters, which Lee says are from people "who just want to say thank you. They're really gratifying."

But there's no substitute for the adulation of the crowds, and as Lee speaks, the band is finishing rehearsals for its fall-winter U.S. tour (which began in Green Bay, Wisconsin on September 3). Their entourage of stagehands and roadies remains intact, which is typical of Rush's organization: Just as they relish privacy, they covet stability, having used the same producer (Terry Brown) since *Rush* in 1974 and the same manager (Ray Danniels) from the beginning. "I really like that consistency," says Lee. "There's enough change going on around us."

Rush have almost single-handedly advanced heavy metal beyond a mere onslaught of volume, density and cries of nihilism. It seems, given the current state of heavy rock, in which everything sounds like rehashes of *Led Zeppelin II*, that few have picked up on Rush's lead. Lee agrees.

"It all sounds the same now. At one point it all came charging back and had a lot of energy, but it hasn't really gone anywhere. It's just become a commercial thing, all pasteurized and homogenized. Anyone can pick up a book and say, 'Hey, let's learn how to be a heavy-metal band: a) Get lots of amps. b) Have lots of explosions. c) Dress up and d) Let's use these four chords...'

"I think it's gotten really terrible."

But ironically, that lack of vision, and perhaps ability, of their peers has heightened Rush's impact, and is one of the reasons so many fans look to them for musical excellence - there's not much else out there.

"Yeah. I'll tell ya, about our technical prowess...

"It seems as we've grown, the music around us has gotten simpler. Everything around us," Lee concludes with a chuckle, "is legitimizing us all to hell!"