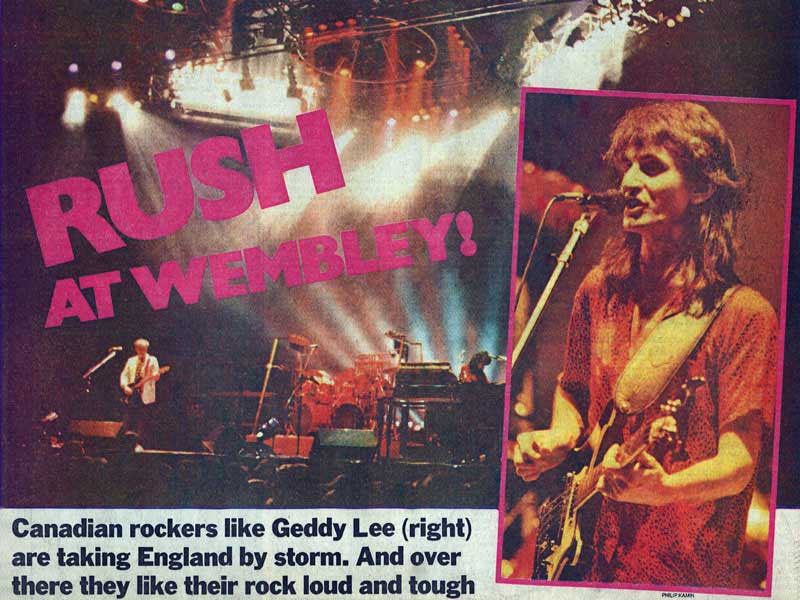

Rush: Rush At Wembley!

Canadian rockers like Geddy Lee are taking England by storm. And over there they like their rock loud and tough.

By Peter Goddard, Toronto Star, May 22, 1983, transcribed by pwrwindows

LONDON - "Oi matey where's your 'ockey stick?"

The pictures flashing along to the music at the back of the stage are pure Toronto. There's the old City Hall, Scarborough, a typical high school hall, the CN Tower. Everywhere else the accent is pure cockney.

Rush is at Wembley Arena for an unprecedented four evenings, which ended last night. It's probably the greatest coup here by any Canadian act ever - The Toronto Symphony and Pierre Trudeau included. And the boy standing beside me, born and bred not two blocks from here in northwest London - the one who is screaming at Geddy Lee, the band's bassist and singer - thinks he's the all-Canadian cockney kid.

He's wearing a Montreal Canadiens sweater. He's got a Blue Jays cap. He's got tiny, red, Maple Leaf stickpins all over his Rush jacket. Holy hockey pucks! He even has a beaver stitched on the back of it. It probably glows in the dark. Rush's music these days is a gridwork of textured electronics. This music is as broad as a symphony and has the honed intensity of a buzz saw.

Spirit Of Radio, Subdivisions - you can feel each of these songs shake this old hall, where the bodyguards wear pinstripe suits, and shake it to its foundations. It's a celebration of power. And our all-Canadian cockney kid is totally lost in it.

This is, by any standards, rock 'n' roll success (David Bowie will do only three nights when he's here early next month). It's showing you've made it in rock's own backyard, the suburbs of London. It signals something else even more remarkable, though - the growing Canadian presence in British pop.

Talk about sending coals to Newcastle. Martha and the Muffins, perhaps our premier new wave band, have been playing in and around this city all week.

Anvil, a new Toronto-based heavy metal band starts a 31-day tour at Chippenham next Friday. Santers, another heavy metal band from T.O., was in St. Albans last night and is in Hull Tuesday for its 18-day tour.

Saga just finished recording a new album north of the city. Lee Aaron just finished some club dates.

It's nothing particularly new for Canadian pop to be exported over here, although it's always been viewed as some rough and rare bit of colonial craftwork. Gordon Lightfoot and Anne Murray have toured here on occasion. The Nylons just left. But, like The Toronto Symphony's recent swing through this way, many of these forays have amounted to testing the waters.

That's changed. What's happening now amounts to a flood of sorts. Rough Trade has just released its first single (All Touch) and first album (Shaking The Foundations). Hit parade charts, far more crucial here than in North America, list Montreal guitatist Frank Marino, Aldo Nova, April Wine and the band Toronto. On radio, you can catch Triumph's album Never Surrender, Kim Mitchell's mini-LP and the Headpins.

"Rush started it all years ago," says Willy Bagnell, Santers' manager. "They proved England was another market for North Americans." And Rush certainly have made the most of it.

"They came along when a number of big British bands like Yes started to fade away," says Alan Lewis who edits Kerrang, the hot pop magazine dealing only in heavy rock. "They proved to the kids here that rock can grow up - and still be tough."

What Rush started, in effect, was this whole idea of toughness. They've since gone beyond it. But it's taken on a life of its own.

Pete Makowski, a writer with Sounds, calls it "Canuck Power." Think of it as the '80s version of The Wild Colonial Boy. Earlier generations may have thought of the Canadian abroad as being "nice," as Hemingway described one Canadian couple in The Sun Also Rises or "remarkably pleasant," as one visiting Vancouver industrialist was recently described in a Sunday newspaper here. The newer generation sees us another way.

Guitarist Alex Lifeson tears off a solo. "It's really loud - loud - it's like running into a wall," says the all-Canadian cockney. "I can relate to it." His hands are fluttering wildly in the air. He's copying every motion Lifeson's fingers are making.

Well, who would have guessed it? Nice folks like us being greeted like,,, well, Attila the Canuck. When it was discovered that Anvil was going to appear here, Makowski anticipated it as, "What will undoubtedly prove an orgy of reckless partying, insomnia, studs 'n leather."

As soon as another critic, Dave Roberts, heard Santers, he was sure "somewhere in Canada there must be a factory manufacturing rock trios - the number of bands fitting this description to emerge over the past decade is quite remarkable."

Rush is beyond this kind of primitivism, but not completely, and that's the key. Rock began here as an act of defiance. It remains this way when, in North America, it's becoming really another branch of show business. "Pop is still an alternative culture here," says Kerrang's Lewis. "It's something the kids can get lost in. Rush, with their power and lyrics, allow the kids to get lost.

The kids in Britain are not all right, he points out. "There's not so much for them to do here and there's not so much money for them to do it." he says. "They need to get lost in music. They have to."

This growing dissatisfaction has been seized on by labor leader Michael Foot, who is pledging massive spending programs for youth, if his party is elected in next month's general elections.

"We are going to have to put a stop to young people leaving schools without jobs," he told a Lancashire rally last Tuesday.

But this dissatisfaction has also been the source of the resurgence in British pop - the life and style as well as the music.

It is, of course, still in the streets. Clubs around town, from the Fridge in Brixton to the famous Marquee in London, are busting with new bands (Hanoi Rocks or Sex Gang Children) and new styles (the hottest being a blend of African rhythms with bop, jazz and rock).

"England is still the key to the pop world." says Tom Williams, who's Toronto-based Attic Records is hustling Triumph and the Nylons, as well as Anvil, over here.

"And, because so much attention is paid to it, Australia and South Africa, other colonies as well, all look to England. So does Germany and Japan. There's a lot of pop press in England and, if you're noticed by it, you're noticed around the world."

Santers expect to lose "up to $200,000" by next year during their tours in England, Bagnell explains. But it's an investment. "Rush has proved there's a market here for Canadian bands, particularly the kind of band that likes to play live.

"Rock is pretty soft in North America, but it isn't here. That's because this is a country that still judges rock on how it sounds live. It's still a jeans-and-T-shirt music here. The kids may not have much money, but everybody can afford jeans and T-shirts.

Rush started this way too. This past year they played to more than 1 million people. But, in the beginning, 15 years ago, manager Ray Danniels helped raise $9,000 needed to record the first album. It was trashed by critics. So the band went to work, playing over 200 dates a year. Playing live here has paid off.

Martha Johnson of the Muffins admits that "what happens in England carries a lot of weight in Canada." The band, which once had a hit here with Echo Beach, is "trying to re-establish itself after the release of its new album, Danseparc.

Stylistically it fits more readily into what you hear around here than what you hear in North America. Earlier songs by the Muffins were cool and detached. Danseparc is hot and involved.

Britain's continuing influence is due to Canadian provincialism, maintains Bernie Finklestein, who manages Bruce Cockburn and Rough Trade. "Canadians considered Bruce to be a parochial act until he had his hits in Italy. And it's Rough Trade's big success in Australia that's helped them in Canada. We still need the okay from somewhere else."

It's pitch-black by the time the band's finished. They've headed back to their downtown hotel as the all-Canadian cockney kid and I make our way through the crowd.

He is ecstatic. He says that by next year he'll have saved enough money to see for himself where Rush comes from.

"Willowdale," he says his eyes gleaming as if it were Xanadu. "Do you know it?" "Sure," I tell him, always aiming to please. "I live in one of its suburbs -Toronto."