Innerview - Neil Peart

Innerview with Jim Ladd, 1984, radio program transcribed by Will Collier

This is Innerview, an inside look at the people whose music has changed our lives. Good evening, everybody. Tonight, we welcome back to Innerview a Canadian trio that has blended virtuoso musicianship, technical excellence, and visionary lyrics into a one-of-a-kind musical statement. And the man responsible for writing these visionary lyrics is our guest tonight. I'm Jim Ladd. Welcome to an Innerview with Neil Peart of Rush.

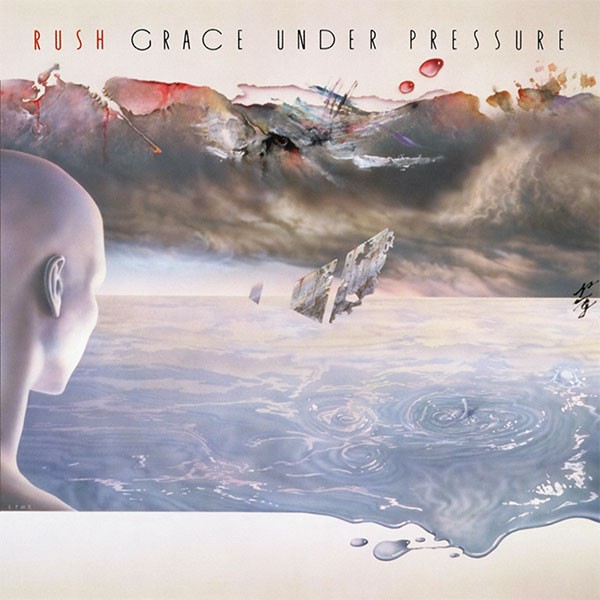

On Rush's most recent LP, Grace Under Pressure, drummer and lyricist Neil Peart explores a wide range of subjects. The leadoff track, "Distant Early Warning," looks in part at our very tense world situation, where the individual can be swallowed up by the masses.

The main theme of the song is a series of things, but that's certainly one of the idea[s], and living in the, living in the modern world basically in all of its manifestations in terms of the distance from us of uh, the threat of superpowers and the, uh, the nuclear annihilation and all of that stuff, and these giant missiles pointed at each other across the ocean. There's all of that, but that tends to have a little bit of distance from people's lives, but at the same time I think it is omnipresent, you know, I think that threat does loom somewhere in everyone's subconscious, perhaps. And then it deals with the closer things in terms of relationships and how to keep a relationship in such a swift-moving world, and it has something to do with our particular lives, dealing with revolving doors, going in and out, but also I think that's generally true with people in the modern world where, uh, things for a lot of people are very difficult, and consequently, work and the mundane concerns of life tend to take precedence over the important values of relationships and of the larger world and the world of the abstract as opposed to the concrete, and dealing with all of those things with grace. [more of the song is played] And when I see a little bit of grace in someone's life. like when you drive past a horrible tenement building and you see these wonderful pink flamingos on the balcony up there, or something like, some little aspect of humanity that strikes you as a beautiful resistance if you like.

A Lawn Boy on a concrete driveway.

Really. Some kind of graceful adaptation, I would think, because you can't hope to overcome what life is made up of today, you know, you can't run away and hide somewhere, you can't really beat the size of it, so you have to learn to adapt, which has been a key word in my thinking for the last few years, where change can't really be affected by the individual person so what you have to do is increase your powers of adaptation and dealing with those pressures.

I think in a major case, a group of individual people can certainly still make something happen, but it seems so futile, as mad as I get at authority of all kinds when it comes to government, when it comes to churches, when it comes to moral majorities and all these ridiculously ignorant societies that are permeating our culture trying to tell other people what to do. You can't really fight those as an individual person, but you can fight them through education with a lot of individuals. You know, I think that's happened in American history several times, where public opinion has changed things. It got prohibition repealed, I think it got the Vietnam War stopped, I think the power of public opinion sometimes can be overwhelmingly strong enough to change virtually anything, but with such a big problem as nuclear arms, for instance, as the America and Russia thing, it's impossible because public opinion can never exist in Russia. If you could get tremendous anti-bomb activity going in America, that would be wonderful, but it's still only half of the problem. You cannot get that kind of activity going in Russia, and consequently, that wave of public opinion can never be brought to bear.

I'm Jim Ladd, and we're back now with Neil Peart of Rush, as the conversation turns now to the song "The Enemy Within."

It's part one of a trilogy but it's the last one to appear. The last three albums have each contained a part of that trilogy, and I started thinking about them all at the same time, but they appear in the order in which they were easiest to grasp. In other words, "Witch Hunt" was the first one, dealt with that mentality of mob rule, and what happens to a bunch of people when they come together and they're afraid, and they go out and do something really stupid and really horrible. That was easy to grasp, and you see plenty of examples of that in real life as well as in fiction and in films of course, too. So that was easy to deal with. The second one was "The Weapon," and it was dealing with how people use your fears against you, as a weapon, and that took a little longer to come to grips with, but eventually I got my thinking straightened out and the images that I wanted to use, and collected them all up, and it came out. And then finally, "The Enemy Within" was more difficult, because I wanted to look at how it affects me, but it was more than about me. I don't like to be introspective as a rule. I think I'm gonna set that down as my first rule, as "never be introspective!" But, uh, I wanted to, at the same time I wanted to write about myself in a universal kind of way, I want to find things in myself that I think apply.

You're writing, you know, it, it's always impressed me as being very, very human, yet, and it deals with very human things sometimes, but it is not very introspective.

No. I don't like to write in the first person unless I'm adopting a character in a fictional sense, like "Red Barchetta" of like "Red Sector A," where it's a person to whom things are happening.

But even those that you mention, they're certainly not-

They're certainly not about me, no (laughs).

They're not about someone who's sitting [unintelligible]-

No, no, but I'm speaking of the types of the persons that you can choose to write in. You have the first person, the second person, or the third person. The only time I would use the first person is that when it is, in fact, a third person. But you use the first person so that Geddy can sing it with more conviction, and play a part in a, in a dramatic kind of way that, you know, a good singer can become an actor, almost in an operatic kind of way I guess. Um, for Signals in fact, I used the third person singular a lot, it was always 'he' to whom it was happening, and this was just some nameless, formless character that I created as kind of an underlying theme. I was, for some reason it appealed to me that there was an underlying person who lived in the subdivisions and who lived through the pains of adolescence and who was the analog kid and who was the digital man and who was the person in "The Weapon" against whom his fears were being, ah, used. And this album, there's a lot of second person, it's all about you. And in fact, I'm always writing from the same point of view and it's always what would I call the camera eye point of view, you know, which I dramatized that in the song of that name, but it's a device that I use a lot. Particularly on this album, it's based a lot on observation, and I like to see myself just as the lens, and try to assimilate what I see, you know, not looking within, and not using a microscope, but just looking straight on at things and seeing what they are, and also equally importantly is seeing what they could be, too, you know, not losing track of the ideal for the sake of the realistic.

Privately, without giving an example, are you a very introspective person?

Self-absorbed is the euphemism-is the word I use.

Self-absorbed?

Yeah, it's a thing I'm fighting more and more because I don't think it's good, it's that I tend to get wrapped up in myself and what I'm reading and what I'm thinking about and all that, and (series of pauses and false starts) it kind of subtracts from the enjoyment of life, really. You know, a lot of it is non-productive. I mean, it's good to be reflective, I think, it's good to think about things after you've seen then and not just to let sensations rush by you, like a TV or something, so I like to look at things and think about them but, um, introspection, perhaps self-absorption, perhaps they are synonymous. The word I yell at myself about is, "don't be self-absorbed!" (laughs)

And that's, that's the point I'm getting to. Are you the kind of person who yells at yourself a lot?

Absolutely, I'm a true Anglo-Saxon in the sense that I have a little judge who sits on my shoulder constantly and yells at me all the time on stage he yells at me for making mistakes, for playing too fast, for playing too slow, and in some ways you can use that little judge as, make him a fan, okay? Say, I'm a fan of this band, what do I think as a fan would be the right decision? If this were my favorite band, what would I be proud of them for doing? Or, you know.

Oh, so turning to make judgment on positive points as well as on negative-

Oh, absolutely, yeah, I don't mean by any means it's some dark, you know, satanistic kind of think lurking over my shoulder by any means. Sometimes he's really nice to me.

I see.

Sometimes he says, "you did a good job," sometimes he says, "that was really nice, what you did." So it works both ways, and that's why I say it's partly very satisfying as long as you keep a good balance on an aspect in your mind like that.

We're back with the second half of tonight's Innerview with Neil Peart of Rush, and I asked Neil if the song "Red Sector A" is based in part on the Nazi concentration camps of World War II.

I was moved to write it by the, I read a first person account of someone who had survived the whole system of trains and work camps and Dachau and all of that, and this person, she was a young girl, like thirteen years old when she was sent into it, and lived in it for a few years, and then, uh, through first person accounts from other people who came out at the end of it, always glad to be alive, which again was the essence of grace, grace under pressure is that though all of it, these people never gave up the strong will to survive, through the utmost horror, and total physical privations of all kinds, they just never, ever wanted to be the ones who were shot, you know, they were always the unlucky ones, which was an important thing that I wanted to bring out. And also, what I learned from the first person nonfiction accounts that I read was that these people would keep their little rituals of their religion, and whatever, and if it was supposed to be a fasting day, even if they were starving to death, they would turn down their little bit of bread and their little bit of gruel, because this was a fasting day, and they had to hold on to something, some essence of normality, you know, that was important. And that moved me, you know. That's, that's intense.

I wanted to give it more of a timeless atmosphere too, because it's happened, of course, in more than one time and by more than one race of people. It happened in this very country in which we sit, it happened, you know, the British did it, no one can set themselves above that, slavery rather involved how many countless countries in terms of the commerce of it all, and people shipping them around like animals and all of that. And no one can set themselves above that in a racial or nationalistic way. So I wanted to take a little bit out of being specific and, and just describe the circumstances and try to look at the way people responded to it, and another really important and to me really moving image that I got from a lot of these accounts was that at the end of it, these people of course had been totally isolated from the rest of the world, from their families, from any news at all, and they, in cases that I read, believed that they were the last people surviving. You know, the people liberating them and themselves were the only surviving people in the world, and it sounds a bit melodramatic put into a song I realize, but the point is that it's true, so, you know, I didn't feel like I needed to avoid it as being over-dramatic, because, you know, I heard of it and read of it in more than one account.

For the track "Red Lenses," Neil introduces a different side of his lyrical style, one that pays tribute to some of his favorite writers.

In a deeper level, without wanting to get too profound about it, but its a style of writing which I've been wanting to get towards, which I've read with John Dos Passos is a prose writer who exemplifies it, T.S. Eliot is a poet who exemplifies it, where they throw so much at you, so many images and so many pictures that are all individually beautiful, not necessarily interconnecting, but they just come at you and they come at you, and all the way through it your head is spinning, and you think, "oh, I'm not understanding this, why am I not understanding this, am I stupid?" And then at the end of it, you sort of put it aside and after the dizziness subsides, you're left with something. You're left with something beautiful. And when one will mention that book to you or that poem to you that story to you, then this beautiful thing, indescribable, intangible, image which you have drawn out of all that comes into your mind. So I just, just wanted to get towards that style of writing where its carefully refined, each little image is worked out so that on its own its something, but all together its a little bit obscure and a little bit vague, so you almost seem to be saying nothing, but in fact you're saying, you know, a great many things.

This was probably the hardest song I have ever worked on, it just, in spite of the pleasure it gave me and how much I enjoyed doing it, it went through so many rewrites and changed its title so many times, everything about it just went through constant refinement, each little image was juggled around and I just fought for the right words to put each little phrase together and to make it sound exactly right to me, so that it sounded a little bit nonsensical. I wanted to get that kind of Jabberwocky, uh, word games thing happening with it and also there's little things going on that your mind sort of catches without identifying, like a lot of poetic devices. You take the, uh, number of words that sound the same or start with the same letter or whatever, you just certainly don't start in the middle of it and go, "oh, that's alliteration!" But those words fall upon your ear in a melodious way, or if you're reading them they, they run through your mind in a rhythmic and attractive way.

Okay, "Between The Wheels," the last song on the album.

Yeah, that was another real complicated one to work on. That one came musically first, uh, when we first went up to northern Ontario to start rehearsing. The first night we get together, we usually have some new technical toys to play with, and we sort of get acquainted again and talk about what we've been doing if we haven't seen each other for a couple of weeks, and just sort of casually sit down and, and work at our instruments and once everybody's sort of happening, in an accidental almost way, things start to drift together. You know, in the same way that it sometimes happens in sound check during the afternoon, where, uh, before we get down to the serious business, we'll just be checking out our things and somebody will start playing and someone else will join in, and something happens. And on that particular night, that song happened, but not just one part of it, the three movements of it, without talking about them, it was quite astonishing, really, that we just started playing with this little piece of music, and a modulation appeared. Somebody came up with a change, and the others heard it, and the next time it came around, we followed it, and we started playing that. By the next time we were going around with this little sequence of ideas, someone got brave and introduced a third idea. Well, everyone goes, "Oh, okay!" and the next time everyone jumps on it. So, we're playing around this circuit of three little patterns which became the verse to the song, the bridge of the song, and then the chorus of the song.

The idea of "Between The Wheels," it was really kind of the opposite of "The Digital Man," in a way. In the case where, the Digital Man, the character is running faster than life, you know, in the fast lane and all of that, just moving faster than, than real time. And then there's the other side of it, where a person is in harmony with time and their life moves along, well, that's very rare. The opposite of that is the people for whole life goes faster than they do, you know. That idea of being in the back water, or watching the action go by, or whatever, to where, the wheels of time, for instance that analogy, some people it picks them up and carries them forward, you know, and it seems to work for them as being mobile wheels. And other people in a real sense without being too melodramatic, are crushed by those wheels. You know, the wheels of change or time or circumstances or history or whatever just roll right over them, you know, obliterate them. [unintelligible comment from JL] Yeah, so there's those two extremes of it, but in the middle, there are the people who are untouched by it, and the wheels of time just roll right past them, and that's what I was getting at with "Between The Wheels" was the fact that these people were neither hurt nor helped by it, but it just rolled, they were observers, sort of, it just rolled right by them and they were in a very sedentary position.

Next to, uh, you know, 'cause the United States and Canada have has such, this great love affair forever, really, you know, the longest border in the whole world-

Yeah, undefended border?

-all of that stuff you know. Are you more nervous today living next to the United States than you were, oh let's say four years ago? [transcriber's note: remember, this is 1984.]

Oh, no, no.

(surprised) No?

I have, I'm a bit of a partisan of the United States, really. I genuinely love America, more than just in a, not in a tourist kind of sense or a superficial sense, but I love everything about America, the good, the bad, everything it is, and uh, I find myself constantly defending it. When we're in Europe, I just argue myself hoarse with those narrow-minded provincial Europeans who have some TV idea of America, you know.

The French think real highly of America, don't they?

Oh, no . . . (both laugh) The French and Germany and Britain, I spend a lot of time arguing with people, and in Canada too. It's a love-hate relationship be far, and in Canada there's a tremendous attitude about Americans, and its weird, these people have never seen any part of America except perhaps Buffalo, New York or Niagara Falls, New York, and that's their whole perception of America besides what they see on TV. And with that ignorance, you know, which is acceptable, because you can't expect everyone to have seen everything and know all about it, but at the same time, don't pass judgment on it, you know, spare me. I've been around the United States a lot, I know a lot of American people whom I love, I respect the country, I respect the people, if I ever have to be in trouble anywhere, I hope it's in the midwestern United States, because there I feel like are people would help me, you know, and not feel like they were doing me a big favor.

That's nice to hear.

Yeah, you know, I have a real love for this country, like I said, not a blinkered love, by any means, and I have no problems seeing the defects, of course. But I know that a lot of those are historical imperatives and the position that America occupies in the world today is not altogether by choice. I mean, it's not people's fault that it became the most successful country and the richest country and the most powerful country, it just happened, you know, because people worked and people were into it, and they did it. So, you can't fault them for being the most powerful and having that incredible responsibility. I mean, it's easy to point fingers at figures in government and so on and blame the government for a lot of things, and of course, there's a tremendous amount of Reaganitis about, but really, it's a bit facile to do that. Anyone who thinks about it a little more and learns a little more about the history of the country and why things are the way they are knows that America didn't go out and buy a bunch of nuclear bombs just so they could be the big guys on the block, you know? It was strictly a historical imperative that they-it's a hysterical imperative. They had to, you know. There was no choice and there is no choice.