Grace Under Fire

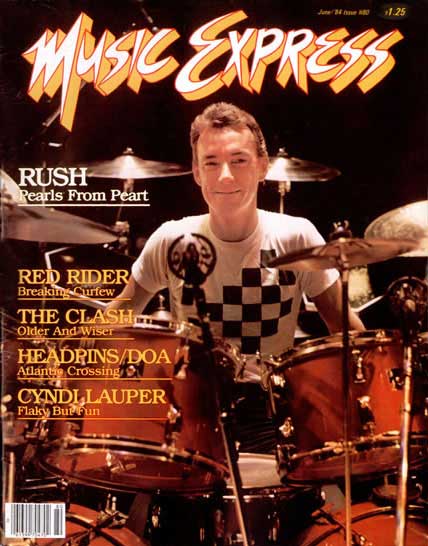

Rush Percussionist Neil Peart Ponders The Meaning Of Life And Other Assorted Topics During This Exclusive, In-Depth Interview

By Keith Sharp, Music Express, June 1984, transcribed by Dave Ward

NEIL PEART GLANCES AT the contents of the two pre-concert tapes he's been programming for Rush's forthcoming, Grace Under Pressure world jaunt, makes a mental note of the music selection and then declares with a beam of satisfaction that, "yes, there is 30 per cent Canadian content in the tapes."

The CRTC boys smile approvingly. The band's legion of faithful punters will first be regaled by the likes of Boys Brigade, the Payola$ and Red Rider before the Rush megaforce re-ignites its bombastic onslaught on the combined sensibilities of its far-flung supporters.

Peart, the articulate lyricist and percussive fulcrum of Canada's top musical ambassadors, is contemplating the band's demanding tour schedule in the same way an advertising consultant would plan a marketing campaign.

"There's talk of us doing the big stadiums like The Astrodome and The Cotton Bowl, but I'm not sure I like the idea," ponders Peart as we sip coffee in the kitchen of his pleasant but surprisingly unpretentious Toronto residence. "I hate the idea of 50 or 60,000 kids paying top dollar, then having to watch us on a video screen - it seems so artificial. We've clung tenaciously to the 18,000 capacity type arenas because we feel comfortable in them, but the demand is such right now that unless we expand upwards into larger facilities, a lot of kids are going to be disappointed because they weren't able to see us." This comment is delivered not by some pompous, narcissistic rock star but by a creative individual who is extremely concerned about the interest and well-being of his fans. Peart is cognizant of the fanatical, unswerving support he and fellow Rush cohorts, Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson have received for developing their trademark techno-heavy metal sound to its present Grace Under Pressure sheen.

The support has stayed loyal even though the new album and previous landmarks like Permanent Waves and Signals have developed significantly from the sword and sorcery, sci-fi escapism of early Rush epics.

It seems from our opening conversation that you are concerned about critics grasping the proper meaning of your lyrics on Grace Under Pressure. Does it bother you when they try to interpret your work.

Sometimes it's fun and sometimes it's frightening. When the reviews nibble around the truth with an interesting tangent, then it can be fun, entertaining and sometimes it shows a new insight that you put in subconsciously - which is healthy. But sometimes its so far-fetched and so propaganda based, particularly when they tale something and interpret it the way they want to. In a way, it's like the Bible. The classic example of something that has been interpreted in many different ways through the course of history - and some of it has been interpreted to say the most horrible things. It's the same thing with song lyrics. Sometimes I get letters from kids telling me a certain song is about my search for the true God - nothing could be further from the truth. But because of their own prejudice, they find it easy to see things with their own personal slant.

Lyrical Message Secondary

It seems to me that Grace Under Pressure is an extremely cold and clinical album.

I wouldn't have thought that myself. I can't come to terms with the words "cold" and "clinical." I know we recorded the album with the implicit idea of maintaining spontaneity.

The stress seems to be more on the lyrical message, with the instrumental passages used to colour the message without any extraneous arrangements.

I hope that is a subjective response on your part (laughs). To me, the lyrical message is always secondary and the music is always first. I take as much trouble with the lyrics as I do because it's the old Anglo-Saxon adage of "if something's worth doing, it's worth doing well," as my father used to say. But I don't envision the lyrics as being the focal point of Rush - it isn't to most people. If I respond to a song musically, then I'll check out the lyrics. But if a song doesn't draw me musically, then it won't draw me lyrically either.

But surely the maturity of your own lyrical development has a direct bearing on Rush's musical progression?

It's heard to be subjective about that. There are a lot of fans, particularly the heavy metal types, who probably don't think our lyrics are important. And there are some fans who are extremely sensitive to what we have to say. As a youngster, I was sensitive to words; I used to read a lot, but I never equated words with music until I started writing lyrics. Only then did I come to grasp with the dynamics of inter-relating words with music.

From Hemispheres on through Permanent Waves, Signals and now Grace Under Pressure, Rush seem to have undergone a series of transitions. Do you view this change as a radical departure from earlier albums of a natural evolution?

I think it's a slow, climbing progress. We haven't been searching stylistically. It's not a schizoid thing where we're desperately trying to find a new persona to erect in front of us. It's just a simple desire to get better. Stylistically, certain influences play a part in our development - I wouldn't want to be shut off from the world of music. Quite often, I hear something I like and incorporate those influences into my own playing. But we've never switched horses completely - we've added new instruments and certain refinements, but the band's songwriting ability is the foundation of everything. We still use complicated instrumental ideas, different time signatures and complex rhythmic combinations. But now we have refined them to the point where we can use them as bridges without having to base one movement or song around one idea.

Natural Evolution

Do you think the somewhat radical changes on your past three albums may be confusing your hardline fans?

I don't think Grace Under Pressure is confusing. Signals was, but it was for a very good reason. With that album and with Permanent Waves and Farewell to Kings, we were trying different things - some of which didn't work. But we didn't know that at the time. It was a case of saying, "Let's try this and see if it works." With six months of hindsight behind us, we can analyze what worked and what didn't. I don't feel negative about it - I just learn from previous mistakes and gain experience from the experiments. I think this album is the ultimate realization of those experiments.

In attaining this natural evolution, you've probably lost some old fans, but gained a lot of new ones who can appreciate your new direction.

We have to hope that's the case. You hope that as you get better, you attract a better class of audience and those that stay with you have to develop the same temporal frame. There's a lot of kids buying our records who were with us during the sword and sorcery sci-fi periods - and that's the same mental framework we were in at the time also. But we've evolved and hopefully they have too.

A lot of your critics see you as "Rock Aristocrats," very detached and insular from rock's mainstream.

That's a subject I dealt with in "Tom Sawyer," how often reserve is taken for arrogance. We've tried to protect our personal lives and that demands a certain insularity from the general public. But that's only to protect ourselves from the poison that surrounds this business.

The interesting thing about the Rush sound is that it provides a common denominator between the seemingly parallel forces of electronic and heavy metal music.

That comes from the combination of diverse influences. I think that we did that in the Seventies. We walked the line between hard rock bands and the English progressive bands. That was the synthesis we tried to draw together. Progressive music changed its bath drastically in the late Seventies and we noticed this as listeners. A lot of it was artsy and fey but we tried to bridge the gap and create a technological edge, yet keep the same emotional values of hard rock.

How do you perceive your own improvement as a lyricist?

I think it inter-relates with the band as a whole. As I grow to be more concise as a lyricist, it relates to our overall improvement as composers and arrangers. To me, improvement means refinement which means being minimalistic. North American writers brought that to this century by cutting out extremist junk and saying what needed to be said without losing any of the emotional impact. Bands like Talking Heads are good at this. They sound deceptively simple because they have maintained the importance of their music while cutting away the excesses.

Sense Of Pathos

Particularly with the last two albums, your lyrical perceptions have undertaken a more socially-conscious outlook.

There comes a time when you stop reading comic books and start reading newspapers. That's the kind of growth you go through. I started to observe my friends and peers and contemporaries and what they were going through. Their problems were also reflected by what I saw on my travels through cities we played in - I couldn't blinker myself from these problems anymore. At one point, fantasy and escapism was moving me away from mundaneness. Now, mundaneness is drawing me back to reality - but with a different sensitivity and more of an awareness, born of maturity. I can relate more strongly to what my friends are going through; the disappointments and disillusionments of life, being ground under by the pressure through no fault of their own. You just can't pretend that life is rosy. The point of the new album, which some critics missed, is one of compassion...actually a better word is pathos. I think of the state of the world and it makes me sad...and then it makes me mad. That's the point of "Red Lenses." People have to get angry because it's anger that gets things done in the world.

The lyrical message of Signals seem to reflect a sense of optimism in the world. However, Grace Under Pressure seems to say that we don't learn from previous mistakes.

"New World Man" expressed the opinion that someone can deal with their problems and "Between the Wheels" on the new album, warns of problems but also points out the alternatives...it warns of complacency: "We can fall from rockets' red glare, down to brother can you spare." It reflects a sense of fragility and the fact that security means nothing. With "Between the Wheels," I wanted to be responding to what I saw in other peoples' eyes. They weren't being carried along on the wheels of time the way my life is; they were being squashed out the way people in concentration camps were - the wheels of life are going by and these people are simply onlookers; they are totally stationary.

What emotion is triggered by "Distant Early Warning?"

That's anger. My beautiful lakes up north are being killed by sulfurous emissions and so-called environmentalists are contributing to the problem. Then I think of friends and more universal problems. I'm not really an eternal pessimist - I'm on record as being an optimist - but I'm worried about the world's problems and I feel it's about time to face things. However, I'm not introspective. I find a lot of things Roger Waters writes are introspective and very dark. I'm not like that.

Public Opinion

It's easy to read the papers and feel helpless about the course of world events.

That's where anger is the key. It starts with worry and then progresses to anger, which is what keeps the sense of outrage alive. I'm not saying people should rise up and burn down the center of government. But they should be angry enough to affect public opinion - from that, things get changed.

Do you feel public opinion carries any clout?

I absolutely do. The Vietnam War would have gone on indefinitely had it not been for public opinion. Once that movement became strong and overtly demonstrative, people in all walks of life spoke about it and the war was ended.

Your writing for this album has obviously been stimulated by current events.

Where we were writing, we got the Globe & Mail delivered every day. My mind is the sharpest in the morning so I'd read the paper over breakfast and pay particular attention to the editorials and the letters to the editor. That's what sparked all these feelings in me. It's a response to other people's feelings, fears and their anger. These are the things I should care about and it was right there in front of me in black and white.

It's hard to imagine Rush as a political band.

No we're not. Politics have never been a modus operandi for me the same way they are for self confessed political bands like The Clash. They have their thing to say and that's fine. But I don't have a quarrel with politics - it's such an immaterial thing except when it reflects bad values. I don't like the extremes of the left and right wing because both have no human values. The inherent dangers are always there.

The inclusion of "The Enemy Within" on this album concludes your "Fear" trilogy which also included "Witch Hunt" off Moving Pictures and "Weapon" off Signals.

Yes, and the exciting thing is that "Witch Hunt" was a production number that we couldn't play live. But now that the other two pieces in the trilogy are in place, we can play the three numbers in sequence which will be a great challenge for us.

Did you write all three songs at once or did the idea evolve over a period of time?

The overall idea was sketched out at the same time but the key was to be able to explain the three concepts of fear; "The Enemy Within" being how fear works against you through government and religion etc.; "Witch Hunt," how fear acts against others (mob rule); and "Weapon" which of course is the machinery of inflicting fear. "Witch Hunt" is a well-documented side of human nature; you see it all the time and it's not hard to visualize, so I went with that first. I wrote the first and second verse of Enemy Within about four years ago and I've had it on file ever since.

Album Overture

I've noticed that most of your albums start off with a key song that reflects the tone of the album and Signals actually had a concept running through all of the tracks.

The concept of Signals was quite accidental, it came down to the running order of the songs, but "Distant Early Warning," like "Subdivisions," is the representative song for the album. It becomes an important facet as to which song you want the public to hear first. The first song works as kind of an overture to the rest of the album. "Tom Sawyer" was that for Moving Pictures. "Spirit of Radio" was the same for Permanent Waves. So we follow a pattern in that sense. The closing song is usually something a little off-base - "Vital Signs" in Moving Pictures, "Countdown" in Signals and "Between the Wheels" on the new one. They are odd songs stylistically...particularly "Between the Wheels," lots of rhythmic changes, it couldn't go anywhere else on the album, it had to be the closer.

How do the album titles correspond with the lyrical messages inside the record?

They provide a nice opportunity to make another statement in context with the album's message. Grace Under Pressure is a really important umbrella that has to stand over all these songs. Judged individually, some of the songs can seem to be too dark for words. But if you make a point from a humanistic point of view, the people in...say, "Red Sector A," the concentration camp, are being graceful under pressure. Despite those horrific conditions, hey tried to retain some semblance of normal living conditions - something they can hold on to. One idea for the album cover was someone reaching out from behind barbed wire to clutch a flower.

Steering away to the more technological side of recording Grace Under Pressure, can you tell us what prompted you to work with Peter Henderson instead of your previous co-producer, Terry Brown?

It was a vague thing because it didn't arise out of dissatisfaction with Terry Brown. It was simply based on our response to other people's music and how they were writing and recording songs. We wanted new inputs so we talked to a lot of producers and asked them how they got certain sounds and how they recorded certain groups. The decision to work with someone fresh came as the end result of this research. We felt we needed a new approach and a different chemistry.

Do you think Peter Henderson provided that new input?

To a certain extent, yes. We'll have to look at it six months hence and make a final decision, but we were happy with Peter. He came into the project quite late, we'd already done the demos and were at the refining stage, so we couldn't use a lot of his ideas. But he was great to work with from a personal point of view and he provided another source of input.

What happened to Steve Lillywhite?

He was our initial choice for producer because of his work with Peter Gabriel, Simple Minds and U2. Quite simply, it just didn't pan out. He was interested, we had spoken with him a couple of times and he came up to look at the studio. Unfortunately, there was just no indication of equivocation on his part - the less said about that the better.

The last few albums have seen Rush experimenting quite radically with new sounds. Have you come to terms with the new technology or are you still experimenting?

I would say adaptation is the key word. Since we did Signals, there's been a whole new generation of electronics, both computerized synthesizers and what we call, "found sounds." The trick now seems to be to take an artificially created "larger sound," refine it and balance it so the resulting sound comes across just as well on your Hi-Fi as it does in the studio. There seems to be a movement back to more established rock sounds which sound better because you're utilizing modern technology. The drum sound can be large without being loud or forcing you to be at war with the guitars.

Has this advancing technology changed your drum style?

Yes, my drum style has changed on this album. I've incorporated electronic drums but only within a given framework of what I wanted to achieve. I knew I wanted to get into more rhythmic sounds like in "Red Lenses" and "Red Sector A," in which I used Simmons drums...but I used them in a very primitive way recording the songs in the first place. The essence of being a musician is to play the songs live, so they are conceived with performance in mind. If you are putting a keyboard overdub on a song and that overdub becomes a prime element in the song structure, then you have to be concerned because that song is going to have to be reproduced live without that element. We set aside the occasional song that we know is not going to be reproduced and pull out all the stops, but it's frustrating to be on the stage and not be able to reproduce a song perfectly. Selecting our material for the new tour is also going to be a headache considering all the albums we've done. We can't really do a medley of our hits (laughs at the thought), but we will put together some snippets of songs and create an overall panorama of material that would otherwise be left out.

Grandiose Tour

I take it the Rush '84 tour will be as grandiose as ever.

Well it will reflect our ability to afford the production costs without passing them on to the kids though inflated ticket prices. There's a lot of groups on the road who can't support the production costs so they have to stick a corporate name on their show. They get the sponsor to pay for the costs which sets a terrible precedent. There will be a time when bands won't be able to go on the road unless they have a sponsor. It will be like Formula One auto racing which is entirely supported by corporate sponsorship. These bands make so many excuses why they need Pepsi-Cola or beer companies sponsoring their tours, but it won't wash with us. The financial investment rarely means reduced ticket prices for the kids. I can see a time when they'll be stopping concerts for commercial breaks, just like they do at hockey and football games. Bands that give into that deserve a good flogging. Commercial music has nothing to lose by corporate sponsorship. Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie aren't compromising anything because they've got nothing to lose - but Rough Trade, yes. When I see bands who I admire, going on tour under the banner of some corporation, I think they're inviting disaster.

It could also be said that videos have changed a lot of groups' image.

Videos can be a genuine thing when they're adjunct to the album, a lot of albums can be disgustingly commercialistic too. I'm not more disgusted by those kinds of videos as I am by those kind of albums.

It's become a Rush trademark to utilize videos and filmclips in your live presentation.

Yes, but it's not something we do to overwhelm the songs, it's just another sensual treat for our audience. The nice thing is that we can use the promo videos for the show or we can use out-takes and rough cuts that were not used in the videos. So long as they add something to the show and do not become a distraction.

Which videos have you filmed for "Grace Under Pressure?"

We'd like to film them all because it's such an image-filled album. But we narrowed the field to four: "Distant Early Warning," "Afterimage," "The Body Electric" and "The Enemy Within." We filmed them in England using three different directors: Dave Mallett, Tim Pope and Cucumber Productions.

Why three different production crews?

We wanted to get different ideas and different styles of creating videos. Like Dave Mallett has worked with David Bowie. Tim Pope has done some obscure videos with groups like Kissing The Pink, Bad Manners and The Cure, and we liked the fact that his videos reflected a wealth of imagination even though he'd been working with low budgets. The Cucumber people specialize in animation and they'd done videos for Elvis Costello, Tom Tom Club and Donald Fagen. Their animation is great, it's full of strange, artsy overlays and they're happy visuals - you can't help but smile at them.

Being a veteran of the road, how do you react to another year of world tours?

It's a love-hate thing with me. I enjoy playing drums live. I like the physical part, the sweat, the workout, two hours a day, that's simple enough. And I like travelling in the ideal sense because I like to look at life from fresh viewpoints - especially when we travel overland. It's not only airport-hotel-arena-airport, we are travelling through the truckstops of America. That keeps your perception of the world healthy. I also respond to the excitement of the arena doors and the kids rushing to their seats - but the whole hoopla of touring, I can do without. The road crew are our friends, most of them have been with us for years, so they provide a form of insular protection from outside interference. But the interruptions on your home life become harder to reconcile as you become more established as a husband and a father. Plus you constantly have to protect yourself from the pitfalls of touring - it's an unnatural environment.

So how do you pass the time on the road?

I read a lot and I use my time constructively. We take French lessons on the road and we try to draw positive influences from touring. It's important to feel that you're always achieving something worthwhile. It's the same when I come off the stage each night. I like to feel that I'm satisfied with my performance, or at least that I did my best. I would be deeply disturbed if I thought that what I was doing didn't mean anything.