Rush's 'Grace Under Pressure': Sometimes the Best Step Forward is a Step Backward

By Dan Hedges, International Musician and Recording World, July 1984, transcribed by Thomas Lloyd

In spring, a young man's fancy turns to batting averages - even in the Great White North. At home outside Toronto, Rush's Geddy Lee is recovering from an attack of baseball frostbite. "It was the windiest game in history," he says, describing hot dogs and umpires blowing across the infield, outfielders suddenly finding themselves in the parking lot, and singles that became home runs in the gale-force breeze. The outing - a precious day off during a time when there is no spare time for Rush - was Lee's humble attempt to put the hassles of preparing for the mammoth Grace Under Pressure tour on the back burner for a few hours. A couple of lazy innings in the sun. A fastball or two. A major brawl at home plate to break up the monotony. That's all he wanted.

The bassist froze his ass off.

But then, Rush's collective posterior, if not frozen, was definitely on the line two years ago after the release of Signals. Canada's platinum-tinged ambassadors of sonic bombast had shifted course away from the Wagnerian, guitar-laden music that had become their stock and trade, toward something more... contemporary. Less turbulence. More sysnthesizers. Non-Rush followers might not have noted any difference, but it was a comparatively streamlined, chrome-plated approach in honor of the newly arrived '80s. Rush: The Next Chapter.

Problem was, many fans weren't thrilled. The album sold, but not as well as its predecessors. Radio continued to play the older tunes but often gave fleeting exposure to the new. The former Ontario bar band that drummer Neil Peart describes as "a self-contained democracy, an autonomous collective," seemed to have made a major wrong move at a point when its status had seemed most secure. That's show business, though Geddy Lee admits the band was unnerved before the LP even hit the stores. "We didn't get what we were looking for on Signals," he says. "It was a very schizoid record. By the time we finished, we realized, 'We're a little lost, we're losing perspective on ourselves.'"

Although part of the problem stemmed from the fact that much of it had been written by Lee and Lifeson independently - without Rush in mind - the bottom line was obvious: too many microchips. As Lee realizes now, "It was good for the synthesizer to take such an important role, for the feel to be shifting in the direction it was shifting, but we felt like we'd lost a member of the band. The guitar went out of focus in the picture. I wrote almost everything on keyboards. Everybody got into the sound because it was new. Like, on 'Subdivisions,' we built these very thick washes; great from one point of view, but it's very difficult to get a guitar to cut through. Here's this very talented guitar player who didn't feel like he had enough to do. Alex was getting frustrated."

Neil Peart, at home a few miles from Lee's place, doesn't view that album through such a dark lens. Citing it as "period of experimentation, certainly worth it," he took the public's opinion with a grain of salt. "From 2112, we were greeted with all kinds of negative reaction from the back benches," he says. "We found that too with Permanent Waves, when we started stretching out texturally and putting in keyboards for the first time. Every time you change, you're greeted by the reactionaries. Part of that is 'the business,' but also - unfortunately - part of that is your fans. You have to recognize that some are as conservative as any old banker when it comes down to what they'll approve of and what they won't."

Echoing Peart's belief that to go into the studio fearful of fan and radio station reaction is "a poisonous and unhealthy way to exist," Geddy Lee nonetheless admits that "I'd be lying if I said I didn't give any thought to that. But it's a fine line. It's going in to make a great record that could sell, or going in to make a record that will sell, and could, by accident, be great. We believe the better the record, the more people will like it."

Still, Signals was a shaky item. Lee concedes that, audience-wise, Rush "probably lost some of the headbangers, the real guitar heroes." Possibly to rekindle lost interest, the new album, Grace Under Pressure, was preceded by a certain degree of prerelease record company blathering about Rush's triumphant return to the halcyon days of yore, to what Neil Peart calls "our baroque period" - the epic era of Permanent Waves (1980), Hemispheres (1978), A Farewell To Kings, (1977) and the founding of Canadian Civilization As We Know It.

"The guitar's louder than it was on the last record," Lee says with a laugh. "That's why they're making those comments."

He's right. If anything, Grace Under Pressure (recorded at Quebec's Le Studio) picks up from where Signals left off, albeit in less synth-happy style. Lifeson gets in his fair share of licks this time, even as the band travels farther along the more spacious, sparer track that drew so much flack last time around. This time however, Lee claims they had a clearer notion of what they were out to achieve.

"We've just tried to sharpen the focus a bit," he explains, pointing out that synthesizers are still in the picture, but that Rush have come to terms with what machines can and cannot do. "We as a band are torn because we're a performing band. We sit here and go 'Well, we like the way the Tears for Fears album sounds. It would be nice to get a similar sound on Rush records.' But after analyzing an album like that, we realize it was made with a machine that only sounds like it hits a drum on every beat. There are no other drums. No wonder all the synthesizers sound so clear - there's no guitar, or at least none that anyone's hitting with any kind of fervor.

"It's a different animal. We try to apply some of these things to Rush, but we have a drummer with the largest drum kit ever created. The guy likes to use everything, every overhead cymbal. So all of a sudden, you have this whole range of ferocity coming through in an area where these other bands and albums don't have anything. 'And now, here's Alex Lifeson, lead guitar player.' He's not content to have a sound that's not emotional, that doesn't move him. To try and get that soul with all this new technology and crystal clarity is a tall order. That's what we've been chasing. Making Grace Under Pressure, we realized part of that is just not meant to be."

The new album marks a change in producers from old compatriot Terry Brown to Peter Henderson (Supertramp's Breakfast In America), a move Lee viewed as essential after a decade, if only to work with a new set of ears. "It wasn't that we were dissatisfied with anything we'd done with Terry. It's just that we'd become so close that nobody was objective anymore. We didn't trust ourselves."

If there was a step backward - at least technology-wise - it came out of Henderson's discomfort with the newest digital studio techniques. While Lee himself admits he's never heard anything special in digital, he says the band went along with Henderson's decision to take them back to analog "for the first time in about four albums. The results didn't suffer. Mind you, this is the first time we went to half-inch tape, which makes a big difference over quarter-inch."

If Rush are continuing their streamlining process on the musical end, it's reflected in Neil Peart's lyrics. A few years back, the drummer's contributions came under fire from certain quarters of the British rock press. Accused of everything from closet fascism to poor taste in clothes, Peart countered that he'd only copped his world view from personal observation, aided my things he'd been reading - Ayn Rand and the like. No sinister overtones intended.

"My perceptions haven't changed," Peart says regarding his lyrics on Grace Under Pressure. "They've just grown enormously. I'm saying the same things but saying them in a lot of different ways, taking it from different viewpoints, and seeing other people's part in it all a lot clearer. I don't have antipolitical feelings against anything. You have to judge by acts. If I see terrorism from a dictatorship or from a collective society, if I see people getting murdered, then I object to that."

As Geddy Lee points out, Peart's new lyrics continue the universal thread the band has followed all along, but "in a more mature way, without so much of a chip-on-the-shoulder attitude."

Like the music, the verbiage itself is sparser, due to what Peart says is the band's goal ("to have that kind of economy but still cover the full breadth of emotional power"), and his growing belief that "sometimes things don't have to be clear. It's a style of writing I'm consciously going after now - to seem to be saying nothing, but to seem to be saying a lot of things. T.S. Eliot is the writer who's most influenced me on that. He had so many images going on, so many metaphors, that his writing is in one way meaningless and in another way tantalizing. I'm concentrating now on avenues, on specific applications of those earlier large ideas."

A decade after the current lineup joined forces, Peart still views its trio status as "a limitation that we can work within, though we try to push outside those limitations as much as we can." But as Lee explains, "With this album, at the last minute, we started to get a little reckless and said, 'Well, fuck it. I'd like to put this sound on because look what it adds to the song. We'll worry about reproducing it afterward.' We've come to realize that you can reproduce something even if you do go overboard on the record. With the way synthesizers are now, you can always find a sound that will work live for what four sounds had to do in the studio. "But we make a lot of our decisions by judging how we felt as fans. I remember when I used to go see Jethro Tull or Yes. I used to sit and sing every word. It was real important to me that my hands hit the air keyboard or made that air-guitar chord happen exactly where it happened on the record. So a little bit of that has kept us trying to reproduce everything exactly, for the kind of fan who's into every note on the record."

He says things are slowly loosening up. Rush are moving away from the compulsion to make every concert a carbon copy of the one before it, every live arrangement a Xerox of its vinyl counterpart. For instance, the band is playing the now-complete "Fear Trilogy" on its current tour, including "Witch Hunt" from Moving Pictures. With its zillion-and-one overdubs, the piece has previously never been performed in concert, something new keyboard technology now makes possible. The band, Lee admits, literally learned it off the album the same way any of its aspiring musician/fans would. "It's a different animal, playing live," he agrees. "Maybe it's not such a bad thing that the songs are arranged differently. Maybe that'll make them more interesting for people."

But while the music, 10 years on, is what he, Peart, and Lifeson obviously still view Rush as being all about, he's found there's more to rock stardom than they originally bargained for; "a lot more responsibility to a fan in many small ways that aren't directly related to plucking a string. There are a lot of people around you in this kind of situation who are always going to tell you, 'It's fantastic.' Not getting complacent or letting someone else make the decisions we think are important - that's the hard part. That's where the pressure comes from.

"The more responsible you want to be in what you do, the more pressure there is to deal with," lee says, hoping the ball game he's driving to will be a less chilling experience than yesterday's; hoping Grace Under Pressure gets the support he feels it deserves. "This album is a statement, a personal thing saying, 'Look, I want to keep doing what I do. I know there's a lot of pressure on me, but I don't care. I'm going to maintain.' That's the ideal to aspire to. Whether we actually get there or not, whether we have that kind of grace, who can say? But we're hanging in."

Geddy Premium

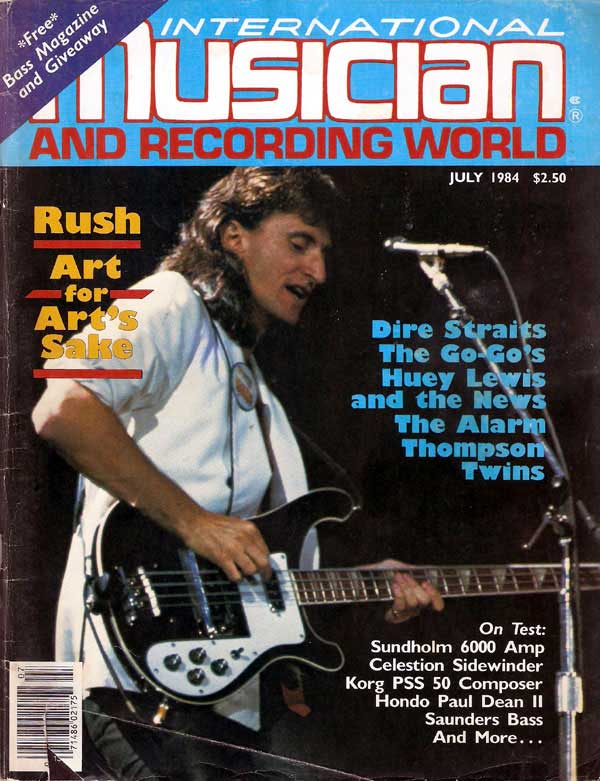

Basses: Rickenbacker 4001, Fender Jazz, Steinberger.

"I used the Steinberger for a few songs on the last tour, but I'll be using it this year for about half the show. I've talked to bass players who really hate the thing, and others who really love it. I don't think there's an in-between. I really like it a lot - the sustain, the fact that it's well balanced. It's the only bass since the Rickenbacker and the Jazz that I've really got off on playing. It feels very warm to me. Plus, because it doesn't have the headpiece at the end, I bang into the microphones a lot less when I'm turning around! I've put the double neck to rest. It was giving me a stooped shoulder, and I didn't have the energy to carry it all night anymore. This is maturity! It's the realization that you don't have the same shoulders you had when you were twenty-three."

Strings: Rotosound Round-Wounds (for the Rickenbacker and Fender Jazz).

"On the Steinberger; I use the ones that have the satin finish. I think they're Rotosounds specially made for the Steinbergers. They don't rip up your fingers quite as much and have a little smoother sound."

Keyboards: PPG Wave 2.2, Roland Jupiter 8, Oberheim OBX-A and sequencers, minimoog.

"I got the PPG while we were writing the new album, and I think it inspired a lot of change on the record from a writing point of view. It has a much different sound. I'm using it this year as my dominant live keyboard."

Amps: BGW power amps, custom sized cabinets, Alembic preamp, Furman parametric equalizers, API 558 EQs, Myer Sound monitors.

"I'm using the Furman parametric equalizers as preamps for these EQs I discovered in the studio, API 558s. It's a very forgiving EQ. You could put it at 800 cycles and crank it 90 volts, and it wouldn't sound cranked. It gives the lift you're looking for without sounding over EQ'd. I'm using them on all the basses, with the exception of the Rickenbacker. I've gone for an Alembic preamp for the bottom end. I still run my Rickenbacker stereo, and it was sounding a bit clunky and sterile on the last tour. I thought it was time to go to a warmer sound."

Alex Lifeson plays Hentors guitars through Marshall amps. Neil Peart backs up Lee's contention that he plays "the largest drum kit ever created." Actually, he has two sets, the main one consisting of Tama drums (two 24" basses; 6", 8", 10" and 12" concert toms; 12", 13", 15" and 18" closed toms; 22" gong bass; 14" Slingerland snare; 13" metal timbale) and Zildjian cymbals (8" and 10" splashes, 13" hi-hats, two 16" crashes, 18" crash, 20" crash, 22" ride, 18" pang, 20" China type, one China cymbal). His second kit has a Tama 18" bass, Slingerland snare drum, three Simmons tom modules, one Simmons snare module, one Simmons Clap Trap, Zildj ian cymbals (22" ride, 16" crash, 18" crash, 13" hi-hats), and orchestral bells, temple blocks, tuned cowbells and windchimes.