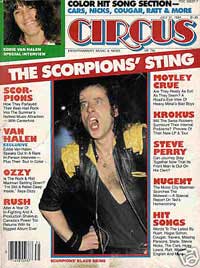

Aging With Grace

By Michael Smolen, Circus, July 31, 1984

Barring the band's riotous five-night stint at New York's Radio City Music Hall last November, Canada's spirit of the radio, Rush, has been off stage and off the air. Since August of '83 a heated internal struggle to find a new producer was keeping Rush out of the limelight. But now that Peter Henderson has replaced Terry Brown and things have stabilized in Rush's north-woods camp, the group is streaking up the charts with Grace Under Pressure (Mercury) and has hit the road with a show guaranteed to re-establish the band as one of the biggest noises in rock.

"Times are hard out there," insists puckish Alex Lifeson. "We want to put on the best show we can and keep ticket prices reasonable. That's not to say that we've skimped on the show one bit!"

The first leg of Rush's tour will end in Indianapolis on the 16th of this month, at which point the band members will take a six- to eight- week summer vacation with their families. Just two and a half months on the road - and then a major break. A far cry, to be sure, from days gone by when lead singer Geddy Lee gauged the band's accomplishment by the fact that "we could go out on the road for eight months and do exactly what we wanted to do." What gives? Is Rush promoting a new image of the hard-rocker as a mellowed, responsible family man? Not entirely so, according to original member Lee.

"To stay on the road for six, eight months solid would kill all the excitement for us," says Geddy (the multi-instrumentalist), "because we have kids back home and they're growing up. For us to keep doing this as long as we can, it always has to be fun. That's why we make sure we get home and have enough time there, so that when we do come back on the road to play a show, we really want to play."

Nevertheless, with tickets for this tour being scooped up in record time, the band will hit the road again in September and tour straight through until Christmas time - with Japan as a target for October. Known for fantastic visual effects, Rush will be combining a magnificent laser show along with their usual amazing lighting system and rear-screen projection segments. But the true highlight of this year's concerts will be a performance of drummer/lyricist Neil Peart's haunting Fear trilogy ("Witch Hunt," "The Weapon" and "The Enemy Within").

For Rush, the time between Signals (1982) and Grace Under Pressure was ill-spent. Just as Alex, Geddy and Neil relish their privacy, they have also been known to covet stability within their ranks - remaining with the same manager (Ray Daniels) and the same producer (Terry Brown) for 10 albums. Slipping into the producer's chair for their new record, however, was Peter Henderson. Henderson established himself as a top-notch producer by giving Supertramp a sound that brought tears of joy to the public's eye, and dollar signs to everyone else's.

"I guess we got to a point where we knew each other too well and there was no mystery left," claims Lifeson. "We all knew how Terry worked and Terry knew how we worked and everything just became too stable. We wanted to shake things up a bit."

If the shake-up over producers was a major problem for Rush over the last year, the lyrics from new song "Kid Gloves" seem to indicate that this might not be the whole story.

Call it blind frustration/Call it blind man's bluff,/Call each other names/Your voice's rude - your voice's rough./Anger got bare knuckles/Reverse the golden rule,/Then you learn the lesson/That it's tough to be so cool.

Could there have been some unpublicized fisticuffs among the trio? With the tight rein that the band keeps over its private life, outsiders will never know for sure.

"1983 was tough year for us." says Lifeson. "The last tour was a grind, and everybody has been going through some changes. Before Peter, we had a couple of other people in mind we wanted to work with, but things got screwed up along the way and there was a bit of a panic. 'Kid Gloves' is our response to rolling with the punches during pressure."

Thankfully, when Rush emerged from their cocoon of despair this year it was not with an LP so aptly titled 1984, or a concept piece from some California band that wouldn't know a George Orwell concept if it jumped out of a bottle of Jack Daniels.

Work on Grace Under Pressure actually began last August, though the LP didn't disturb the dust of record bins until April. Nine months is the longest time Rush has ever spent incubating a new album. Fortunately for the members of Rush, however, their internal problems sparked a fire of overwhelming creativity

"Guitar-wise," explains Lifeson, "I think the way things are on Grace Under Pressure is a bit of a reaction to Signals. Looking back to Signals, I think the guitar might have suffered a bit; it was lower and smaller in perspective to the rest of the mix. On the new album we went for more of an aggressive sound, a fuller sort of production where all of the instruments have more of a cohesive balance."

The lyrical content of Grace Under Pressure sees Neil Peart maturing as well. No futuristic space musicals here, for Peart, weaned on Jane Austen, Thomas Hardy and John Dos Passos, is slowly losing his penchant for writing technological nightmare sequences. "Words are such an infinite playground," says Peart, "and this style of writing has bolstered my confidence with them and my understanding of different ways of playing with them. It's just like the technique of playing the drums." Sure, there are odes to nuclear war and androids on the run, but also on the LP is a razor-edged poem ("Afterimage") about a friend killed in a car accident, and a chilling account ("Red Sector A") of life in concentration camps.

New rock bands and the recycled styles they claim to introduce come and go as fleetingly as Baskin Robbins' flavor-of-the-month. So, it would seem, do decades. It was exactly 10 years ago that Canada's blond-haired and blue-eyed Alex Lifeson, with Geddy Lee and John Rutsey, released the first Rush album on their own Moon Records label.

The accolades and accusations have run their course, as they do in the case of any long-lived band. Since high-school chums Lifeson and Lee got together in Toronto-area garages in 1969, Rush has garnered numerous gold and platinum albums, record-breaking sell-out performances and a Grammy nomination. But the band has paid the price of fame and fortune. Accusations against it have ranged from critics fingering Rush as an anachronism of the late-'60s, to claims that Neil Peart's Ayn Rand-based lyrics promote neo-fascism and right-wing extremism. None of this has anything to do, though, with the most important part of Rush the music. "Image is not really important," contends Lee. "If there is an image for this band, it comes strictly from the music."

Rush's 10-year career has not been entirely a matter of taking well-earned bows and tripping happily off to the local savings and loan association. Geddy Lee can remember the early days when Canadian music-moguls weren't buying what Rush were pushing. He also remembers being fired from local clubs because the band was playing so loud that barmaids couldn't hear the beer orders. Things did get a little better, though, once Mercury decided to release the Rush album in America, and Lifeson recalls being roundly booed offstage only once. "That was in Baltimore many years ago," says the cherubic axeman. "We played a show with Sha Na Na. It was like a greaseball dress-up masquerade dance, and it bordered on horribleness. They didn't like us at all." But in 1984, the collective known as Rush has emerged as a survivor.

"[Rock music] all sounds the same now," Lee laments. At one point it all came charging back and had a lot of energy, but it really hasn't gone anywhere. It's just become a commercial thing, all pasteurized and homogenized." By contrast, Rush's "Tom Sawyer" and "Red Sector A" show the diversity of a band that cares, but sells anyway.

"I think if you love what you do - and I do - the more successful you become," concludes Lee. "And the more successful you become, the more freedom and flexibility you have. .That's good; that's satisfying. But I'll admit that there's a lot more hard work involved in becoming successful than I ever realized when I was starting out!"