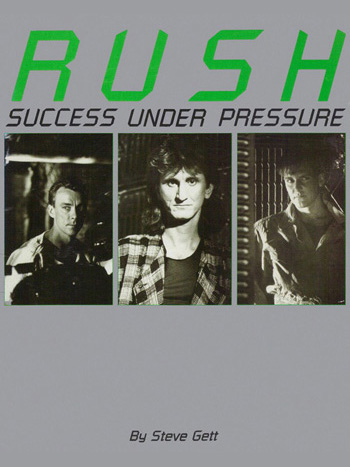

Success Under Pressure

By Steve Gett, Published in 1985 by Cherry Lane Books, 48 pages, b/w photos, ISBN 0.89524.230.3

In August, 1968, top British session guitarist Jimmy Page was in something of a dilemma. For the past two years, he had been playing with the legendary Yardbirds, whose previous line-ups had boasted such worthy talents as Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck. However, after Beck quit to pursue a solo career at the end of 1968, Page had been left to carry the group through the next 18 months, until it finally crumbled under his feet.

While Jimmy was eager to start a new band, the Yardbirds were already booked on a 10-date Scandinavian tour the following month. Consequently, he began a desperate search for accompanying musicians, soon hooking up with John Paul Jones, John Bonham and Robert Plant. Over the ensuing months the group was to change its name to Led Zeppelin and go on to become Britain's most celebrated rock act.

Meanwhile, as Jimmy Page unveiled his New Yardbirds in Europe, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, in the suburbs of Toronto, a young Canadian guitar player, named Alex Lifeson, was busy forming Rush. Although Page was fortunate in enjoying immediate acceptance with his outfit, it necessitated years of hard graft and extreme patience before Lifeson and his band made their mark.

After battling fiercely to break out of Canada, Rush were forced to embark on endless US road outings before garnering major recognition and acclaim. For many years, radio stations ignored their music, and, in the pre-video age, touring was the only means of gaining exposure. Despite the long wait, Rush were to end up selling more records and playing to more people than Zeppelin ever did.

Attempting to parallel the histories of Rush and Led Zeppelin would prove an impossible, and extremely futile, exercise. Yet, it's interesting to observe that each band basically encountered success under its own terms. For both, the major forte was an essential high quality of musicianship, combined with a diverse range of musical styles. Never was there any compromise in their overall approach on the road to fame and fortune.

Led Zeppelin are, of course, sadly no more. However, Rush are still going strong and continue to warrant recognition as Canada's finest hard rock export. Throughout their illustrious history, the group has released a succession of highly innovative albums and delighted concert audiences around the world. Their work has been admired for its breadth of reach, technical elegance, and for the confidence with which it has combined great boldness with artistic poise.

While many top bands are adverse to change, fearing that their popularity might wane, Rush have never been afraid to take chances in order to broaden their musical horizons. "We've always been a fairly experimental group," maintains vocalist-bassist-keysman Geddy Lee. "And one of the reasons we'll continue to be that way is because of the fear of becoming boring old farts! When you reach the stage of being a successful band, there's more and more pressure to stay the same and that is very dangerous. It leads to complacency and pretty soon you end up churning out the same bullshit album after album.

"Complacency is still the biggest fear we have. Making albums or touring with a 'Who gives a damn?' attitude -- that's when it's time to stop. You can get used to being liked and that's kind of dangerous too. There is a little fear that when you do something different, everyone's going to put the 'thumbs down' on it. But, at the same time, if what you're doing is experimental, but good, then people will still like you."

According to drummer Neil Peart: "The initial focus of our music has to always change to keep us interested."

1984 saw Rush celebrating their 10th as a recording band. Following the release of their raw, Zeppelin-inspired debut offering back in 1974, they subsequently produced a series of more techno-rock oriented albums. By the start of the 80's, they had begun to veer away from the marathon musical pieces that dominated LP's like 2112, A Farewell to Kings, and Hemispheres, and have since aimed for a more direct, modern sound. With the integration of keyboards and reggae-influenced rhythmic patterns on recent works like Signals and Grace Under Pressure, the Canadian trio has gone way beyond the standard hard rock boundaries.

Yet, although Rush have garnered a reputation for playing "thinking man's heavy metal", their audiences still comprise a strong contingent from the hardcore denim and leather brigade. "I guess that's because we've grown up in the school of a power trio," recons Geddy Lee. "Even though we do things that are different and experimental, there's still an essence of that in our music. Our songs may have changed, but there's still a lot of power to them."

Away from the scene, the three band members tend to maintain extremely low profiles and little is known of their private lives. "We've all gotten very protective," Geddy admits. "We value our privacy a lot and I think we've learned to put up a wall between ourselves and other people at times. There's a way to withdraw yourself from certain situations.

"As you can imagine, the bigger you get, the less contact you have with the fans. There's the occasion, and I appreciate it when it happens, that you do get to talk to some. Playing in big halls, people are obviously kept back by security. You come in by bus and go straight out to the bus. So there's not much contact at a gig than the faces you see in the front row. But hardcore fans do find you and get a chance to talk. So I don't think we're totally detached; we still have some street contact."

Rush's reluctance to live the stereotype rock 'n' rock lifestyle has led many to assume that they are rather conceited individuals. Quite simply, though, they just take their music and personal lives very seriously. Contrary to certain beliefs, the definitely aren't egotists and have never allowed success to go to their heads.

"I think we got over that really early on in our career," Geddy concludes. "On the first couple of tours that we did, there was a danger of us getting like that. But we realized that making it wasn't going to be easy and that brought us down to earth. We didn't have a big smash hit really quickly. It was a slow build-up and we've had to work real hard to get where we are today."

This book pays tribute to three musicians -- Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart -- who have not only achieved, but have also maintained, success under pressure.

Geddy Lee

Geddy Lee once declared that if he had a nickel for every insult about his voice, he would probably be a millionaire! His high-pitched vocal chords have certainly come under a good deal of fire over the years, but when one considers Rush's popularity there must be an awful lot of folks who favor his unique style of singing. Yet, it's not just with his voice that Geddy has made a name for himself. His tremendous all-round capabilities, both as a musician and a songwriter, have led him to be held in high esteem throughout the rock world.

Originally hailing from the Toronto suburb of Willowdale, Geddy began his musical career as a rhythm guitarist and was forced to switch to four strings when the bassist in one of his early bands quit. After joining Rush in the fall of 1968, he subsequently developed into an extremely versatile bass player. Shortly before the trio recorded A Farewell To Kings in 1977, Geddy took up keyboards in order to boost the group's stage and studio sounds.

"When I first started playing keyboards, I just wanted to use the occasional string line," he explains. "But then I felt they were giving us somewhere interesting to go to; helping us to mold our sound into something different than it was before. It's proved to be a real bonus. It's been one hell of a challenge for me and, to tell you the truth, I do get very excited about using keyboards."

Initially limiting himself to a Mini-Moog and one set of Mood Taurus pedals, Geddy has gradually built up a more extensive collection of equipment that now includes an Oberheim OBXA with a DSX Digital Sequencer, two Moog Taurus pedals, a Roland JP 8 Synth and Roland 808 Compu-Rhythm, and a Mini-Moog with a Yamaha E1010 Delay.

However, he finds it hard to consider himself a proficient player and maintains: "I'm still very much in the dabbling stage. Put me beside any real keyboard player and it's a joking matter. And I don't really pretend that I can play. I can write solo lines and melodies, and play basic chord patterns, which is really all I need. But I certainly don't have any illusions about being a Keith Emerson or anything like that."

While Geddy continues to play bass (generally a Steinberger L2 on stage and either a Fender Jazz or a Rickenbacker in the studio), he finds that he tends to handle most of his songwriting on keyboards -- a fact evidenced by the nature of the band's recent works. "Even before I played keyboards, I still wrote more on guitar than bass," he claims, "simply because, even though the bass is a good instrument to write riffs on, it's very hard when you're trying to get melodies across. So I'd say that keyboards kind of took the place of my writing on the guitar. I feel more comfortable with them and it gives me a different point of view, because looking at 88 keys and the way the notes are laid out in front of you is a lot different to picking up a guitar. Being able to play a little bit of keyboards, bass and guitar gives me a whole range to choose from."

Rush obviously consumes a good deal of Geddy's time, but in recent years he has also managed to work on a couple of outside projects. At the beginning of 1982, he made a guest vocal appearance on the comedy single "Take Off", from the Mercury album The Great White North by Bob and Doug McKenzie (alias "Second City TV"'s Dave Thomas and Rick Moranis.) The record actually made the US Top 10, a fact which took a lot of people, including Geddy himself, quite by surprise.

"I went to school with Rick Moranis," he reveals, "and basically grew up with him. When they were doing the album, they called me up and asked me if I'd sing on one of the tracks. So I went down and it took me all of half an hour to do. It was fun; strictly a fun thing to do with some pals. Nobody had any idea it would get as big as it did."

In 1983, Geddy helped out the young Canadian band Boys Brigade by producing their debut album and he did a commendable job. One wonders, though, whether he has the desire to make an LP of his own.

"Well, I wrote a whole bunch of solo stuff, but that eventually became a part of Signals," he laughs. "I would like to work with other people at some point. I have some good friends who are excellent musicians and I'd definitely like to work on a project with them one day. But I don't really view the idea of a solo album as being a showcase for my 'great talents' that are held back in Rush. If I ever do my own record, it would be along the lines of what I just mentioned -- working with close friends. I can see it coming, but my time gets eaten away so quickly that I can't say when it'll be."

At this juncture, Geddy clearly still views Rush as the best vehicle for his musical output, but, naturally, there will be a time when the group decides to call it a day. Asked why he feels Rush has stayed together for so long, Geddy reasons: "We like each other and still enjoy playing together. Every time we start working on a new album, it's always real creative and exciting. We don't fight a lot; sure we fight, but that's only in real tense situations, whether it be in the studio or because of being out on the road too long -- or if you beat someone at tennis real bad!"

Tennis and other sports, particularly baseball, are among Geddy's main non-musical interests. In fact, he has even expressed interest in running a minor league baseball team. He has been married for a number of years and, when the band isn't on tour or in the studios, he lives outside Toronto.

Alex Lifeson

Born in the mountain fishing port of Fernie, British Columbia, Alex Lifeson started playing guitar when he was 12, having previously made an unsuccessful attempt to learn the viola. His first six-string was a Kent classical acoustic, which his father bought him as a Christmas present, and a year later he acquired a $59 Japanese electric model.

Citing his early influences as Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimi Hendrix and Jimmy Page, he was basically self-taught as a guitarist. The only formal training he underwent was during Rush's early days on the Toronto club circuit.

"A friend I went to school with taught classical guitar," Alex recalls. "He was a very good teacher and I studied with him for about a year and a half. That started around 1971, but then one day he was in a motorcycle accident and had to go to hospital, so the lessons kind of fell off. Also, we'd started to play in clubs a lot more, so I wouldn't really have had the time to keep them up anyway."

The 1974 debut Rush album marked Alex's first appearance on vinyl and it displayed his strong affection for Jimmy Page's playing. At that point, and indeed up until a few years ago, Lifeson generally favored Gibson guitars. Nowadays though, he tends to prefer using a Fender stratocaster, both on stage and in the studio. The latter has certainly helped him to establish a sharp, distinct guitar sound and one wonders what actually precipitated his switch from Gibson.

"When I got my first Fender, it was just a replacement for my original Gibson 335, which I'd had since 1968," he explains. "We were doing a show with Blue Oyster Cult and the rigger who set up the baskets for the PA system didn't tie down the horns sitting on top of the bass cabinets. What then happened was that they vibrated themselves off the cabinets and fell down on top of my double-neck guitar, shearing the pick-ups off and gouging the body. Then, the speaker fell on my 335.

"I couldn't care less about the double-neck -- that was easily replaced -- but the 335 was very special to me. So I took it off the road and got a Fender to replace it. But I couldn't play with it. The neck, the body and the balance were totally alien to me.

"Over the last few years I've started to use it a lot more. I put humbucking pick-ups in the back position and managed to get a sound that was closer to the body of a Gibson, but yet still had the bright character and clarity that Fenders are renowned for. I'd also kept the two front pick-ups as they were, in order to retain that special Fender sound. Gradually, I got used to it. I put on a couple of different necks and now find it very comfortable to play.

"The ironic thing is, though, that I now find the Gibson's feel a little strange at times. They seem a little stiffer, although I still enjoy playing them very much. I was brought up on them and I think my change to Fenders was basically a technical progression."

During recent road outings, Alex has only employed a Gibson during a medley of older material at the end of the show. The rest of his stage gear comprises: four Marshall combos and a wide range of effects, including two Yamaha E1010 Analog Delays, a Delta Lab DL5 Harmoniser, a Roland Boss Chorus, an MXR Distortion Plus, a Cry Baby Wah-Wah... the list goes on.

As far as his studio equipment is concerned, he maintains: "My set-up is almost identical. The only difference is that I might not use the pedal board and go directly into the amp. Or I might set amps up in different positions in the studio to try for different sounds."

Those who have witnessed a Rush concert in recent years will probably have observed that Alex is a lot less mobile on stage than he was in the past and that he rarely indulges in bouts of 'guitar hero' posing. While admitting that this may be true, he assesses: "You don't have to be jumping around the stage like a maniac to put on a good show. If it sounds good and you play everything well, then that's enough."

Like the rest of the band, the guitarist's appearance has also changed dramatically over the past few years. During the 70's, he tended to be seen in satin kimonos and strides, with a long mane of blond hair hanging down his back. These days, he sports a very short-cropped hairstyle and often favors a jacket, shirt and tie as his stage attire.

"I like having my hair shorter a lot more," he declares, "and you can only wear satin pants and boots for so long. Nowadays, I just dress depending on the mood I'm in."

Alex is adamant that spontaneity is the key factor behind his guitar playing and, during his career, he has come up with some excellent lead breaks. He pinpoints the ones on "Limelight" and "Chemistry" as being amongst his most memorable. The solos on "The Body Electric", "Kid Gloves" and "Between The Wheels", from the Grace Under Pressure LP are also particularly outstanding.

Other contemporary guitarists whom Alex admires include Paco De Lucia, Allan Holdsworth, Edward Van Halen, Andy Summers and Rory Gallagher.

When he's not busy working with Rush, he likes to spend as much time as possible at home with his wife and sons, and also in planes! Seriously, Lifeson has quite a penchant for flying and he is, in fact, a licensed pilot. He has also garnered a strong reputation within the group as a gourmet cook.

Neil Peart

Neil Peart took up drumming when he was 13 years old, after his parents had grown weary of him beating up the furniture with a pair of chopsticks and gave him a course of professional drum lessons for his birthday. He was instantly hooked and it wasn't long before he got his first kit, which he affectionately remembers as a "lovely little three-piece in red sparkle." Curiously enough, he is still playing a red drum kit, although it is considerably larger than the one he had as a teenager.

Surrounded by a huge set of custom prototype Tama drums, a glittering array of Zildjian cymbals and a mass of other percussive instruments, Neil has everything he needs to create his highly praised big sound, which serves as the driving force behind Rush's music.

Originally inspired by the aggressive drumming of the late Keith Moon, the young Peart later found himself picking up influences from the more technically oriented rhythmic patterns employed by the likes of Carl Palmer and Bill Bruford. However, he has long since perfected his own adventurous style, which evidences a marked flair for the dramatic. The extended solo spot on the Exit...Stage Left version of "YYZ" is a classic example of his overall dexterity.

Growing up near Toronto, Neil played in a series of high school bands before he decided to move to London during the early 70's, in order to try and further his musical career. Finding that the streets weren't exactly paved with gold, he ended up working as a salesman at a shop called The Great Frog in the tourist epicentre of Carnaby Street. Eventually, somewhat disillusioned by the British music scene, he returned to Canada, where he soon hooked up with Geddy and Alex.

Since becoming a member of Rush in June, 1974 [webmaster note: Neil joined the band July 29th, 1974], Neil has not only established himself as one of rock's most skilled drummers, but also as an extremely prolific lyricist. Much of his inspiration for the latter stems from his keen interest in literature. He actually picked up his first book at the age of six and has since devoted much of his spare time to reading.

After ploughing through countless children's adventure stories, he went on to develop a passion for fantasy and science fiction works, which provided him with an element of escapism from the grim reality of everyday life in suburbia. In fact, this was a theme he later touched upon with the song "Subdivisions", from the Signals Lp, which he describes as "an exploration of the background from which all of us (and probably most of our audience) have sprung."

Neil's lyrical style has altered a good deal over the years and he believes that his selection of reading matter has tended to dictate his own writing approach. On the road, he can often be seen with his head buried in the pages of books and he has listed his literary heroes as Hemmingway, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Dos Passos, Barth and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Peart has expressed interest in writing a novel and, a few years ago, he predicted that he would end up writing by profession and drumming as a hobby. Whether that will happen remains to be seen. In the meantime, Neil has been able to display his writing prowess by providing the text for the band's press releases and tour books.

Rush fans would doubtless revel in further accounts of the group's activities and one can only hope that, as some point, Neil may decide to publish more. Apparently, he actually wrote a complete day-by-day diary on the Moving Pictures tour, which would definitely be most interesting to read.

At the same time, though, the drummer guards his private life vehemently, something I once discovered on a lightning road trip with Rush. Since my time with them was strictly limited, due to the fact that they tend to drive on to the next city immediately after playing a show, I (somewhat naïvely) asked if they would mind filling out a 'factsfile' questionnaire, figuring that it might make for interesting reading. Neil was particularly loathe to involve himself in such an exercise and actually sent me back a written note, which read: "Steve, I don't want to be rude or arrogant about your questionnaire, but these are things I'm not really interested in. I like to talk about what I do, and about what I think, but I'm not vain enough to think my past or my favorite things are of general importance.

"My musical history with and before Rush is well documented elsewhere (many times) and doesn't really bear repeating.

"The point is that I don't really like 'human interest' stories about music or musicians (especially me). As my privacy is increasingly reduced and violated, I defend it more determinedly. People know me as a musician, but like to think they know me as a person. This is an illusion, and one that I have no wish to foster by providing details of my private life. I hope you can understand this. I have no wish to be unpleasant. And, yes, I know I could have answered your questions in the time it took me to write this!

"Yours truly, Neil Peart."

Realizing my mistake, I could only admire the man for his honesty. Indeed, of the three Rush members, Neil appears to be the most reserved character and one suspects that he does not suffer fools gladly. However, this hardly detracts from the tremendous respect he deserves as a creative artist.

Working Men

As the original founding member of Rush, Alex Lifeson is by far the best authority to consult on the group's formative years. The guitarist still has vivid memories of those early days and recalls: "Rush initially started gigging in September, 1968, and the first shows we ever did were in the basement of a church in Toronto. It was a dropin center and you'd get between 30 and 40 people on a Friday night, who'd be served tea, coffee and potato chips, while the band played.

"At that stage, the line-up consisted of myself, John Rutsey on drums and a bassist called Jeff Jones, who'd played in a number of Toronto groups and a couple of fairly successful Canadian bands. But he left after the second gig because he had too many other commitments. We were all very young, though, so it was no big deal and only about 60 people had actually seen us.

"I'd known Geddy for a couple of years and, at that point, I'd jammed with him quite a lot. So, after Jeff had gone, I called him up and I think he expected me to ask if I could borrow his amplifier, which I was always doing! But I asked him if he could come and do a gig with us and he agreed. We went down early and ran through about a dozen songs that all three of us knew. We ended up playing those three times over during the course of the evening!

"Things worked out, though, and after a couple of shows we were offered a steady gig there until March, 1969, by which time we were playing to about 300 people a night. It was steady work and we were getting paid 25 to 30 dollars per gig, which wasn't bad. We'd split that three ways and either spend it in a restaurant or just do whatever we wanted with our ten bucks. Everybody was in their mid-teens and, during the day, we were still going to school.

"In March, we expanded the group and a piano player joined, who ended up becoming Geddy's brother-in-law. He was in the bad for five or six months, but it didn't really work out and in the end he left, followed shortly by Geddy. Basically, things were falling apart and so we broke up. But after a few months we decided to get back together as a trio and things went from there.

"I think the turning point for us was when the drinking age in Ontario was lowered to 18; it had previously been 21. All of a sudden, there were stacks of clubs to play that were never there before. We started working professionally at that point, which was in 1972. Rather than just playing one or two high schools at the weekend, and maybe three or four gigs in the course of a month, we were playing six days a week, with matinees on Saturdays -- week after week after week! We never stopped. You'd do a rotation: play one club one week and then a series of others, before ending up at the first one six weeks later. There was never really a shortage of work and pretty soon we made enough cash to go into the studios."

Towards the end of 1973, Rush played their biggest gig so far, opening up for the New York Dolls at a Toronto concert hall. Having garnered a strong following on the local club circuit, the group had little difficulty in blowing the headliners off stage. Yet, despite their ever-increasing popularity and the fact that they had earned enough money to make an album, Rush faced one major problem -- a total lack of record company interest.

"It was extremely hard for us to get a deal," reflects Alex. "Nobody wanted to sign us because we just weren't considered 'sellable' at the time. In Canada, if you were the Guess Who, then you had a much better chance because you had something that was very commercial, which could be heard on the radio. We always had a strange reputation in the Canadian music industry. Nobody wanted to know us because we were labeled as being too heavy, with a singer who had a crazy voice."

Consequently, Rush were forced to enter the studios without the support of a record label. The band was aided by longtime manager Ray Danniels and his partner Vic Wilson. Danniels had initially become involved with the trio after promoting a South Ontario high school concert several years earlier. However, allocating recording time was extremely difficult, since the group had to keep gigging in order to sustain their cash-flow.

"We had to start work after playing in a club and record through the night," Alex explains. "We'd tear down the gear and go in at two in the morning until eight, when we had to get out. You'd do that one week, but then you couldn't get back in the studios for another three weeks, which was very frustrating. But we had no other options. Without a proper record company behind us, we had to make do the best we could.

"That's how the first LP was done. I think we only spent three days of actual recording, and then a couple more re-doing two songs and mixing the whole thing. It was all done in under a week, but was spread out over several months."

The debut Rush album finally emerged on the group's self-financed Moon Records label in early '74. While later works were to see them establishing their own identity, on the first LP they seemed content to mimic the styles of others, particularly Led Zeppelin. Alex Lifeson's guitar work owed a good deal to Jimmy Page and Geddy Lee was once described as sounding like "Robert Plant on acid!" Mind you one could hardly compare John Rutsey's pedestrian drumming with the mighty John Bonham.

"Finding My Way" opened the album in a raunchy, aggressive manner and its hard-rocking pace was maintained on the ensuing cuts "Need Some Love" and "Take A Friend". The first side was brought to a close by the more subtle "Here Again", on which the strains of an acoustic guitar provided a little variety to proceedings.

Side two kicked off with "What You're Doing", a number very reminiscent of Zeppelin's classic "Heartbreaker". Next up was "In The Mood", the lone survivor in the current live show. This tune, always popular with the fans, was penned by Geddy, but the rest of the tracks on Rush are credited as joint Lee/Lifeson compositions. "In The Mood" was followed by "Before And After" and finally the album ended with "Working Man", the Lp's winner, which featured a marathon lead break from Alex. On the whole, Rush was a very basic heavy metal record, one that was hardly indicative of what was to come in the future.

Although there was now vinyl product to promote, Rush's troubles were far from over. "Our reputation still wasn't good," scoffs Alex. "But we eventually got a break when a powerful FM radio station in Cleveland got hold of the record and started playing it a lot."

The station in question was Cleveland's WMMS and the DJ who picked up on the group was a lady named Donna Halper. Her consistent turntable spins resulted in strong import sales, which subsequently caught the attention of the noted ATI booking agency in New York, who then expressed an interest in lining up some Stateside dates for the band. A tour was finally arranged when Rush signed a worldwide deal with Mercury Records.

July, 1974, saw the release of the Rush album in the US and, at long last, the trio was set to cross the border. However, not before drummer John Rutsey quit the line-up.

Asked to explain the reason for Rutsey's departure, Alex assesses: "It was weird. I'd actually been friends with John for a long, long time -- since we were about eight or nine years old. John was not the easiest person to get along with; he was quite moody at times and I think he expected a lot from his friends. When we got to the point that the decision had to be made, we'd already thought about getting a new drummer for the past year. John was aware of it -- he was very sick at the time -- but after we tried another drummer, we said to him 'It's not working out. Do you think you can get it together?'

"We managed to work for another year, but in the end there was no point because we weren't really getting along very well. Musically, Geddy and I wanted to do a lot of different things and he wasn't really into the idea. He wanted to go into more of a straight ahead rock thing, like Bad Company, I guess. When we sat down and talked about it, he decided he was going to leave.

"We played another six weeks of gigs and, strangely enough, we had the best time we'd ever had playing together. I kept in touch with him for a few years afterwards, but I haven't seen him in three or four years. I hear he's into body-building now and that he did a bit of TV work but, other than that, I don't really know."

John Rutsey's exodus from the line-up actually turned out to be something of a blessing in disguise, since it precipitated the arrival of the multi-talented Neil Peart. During Rush's early days, Neil had played in several bands around the Niagara Peninsula area, before going off to live in England for a year and a half. Eventually, somewhat disillusioned by the British music scene, he returned to Canada, where he hooked up with Rush.

Neil joined the band on June 29, 1974 -- Geddy's 21st birthday -- and settled in very quickly [webmaster note: Geddy's birthday is in fact July 29th, and is in fact the date Neil joined the band]. According to the bassist: "When Neil joined, we were playing material from the first LP and from our club days. So, basically, he fitted in to what was already there and it soon became as close to him as it was to us. To tell the truth, after about six weeks, it never seemed to me that we'd had anyone else in the band."

Rush's debut appearance on American soil was on August 14, in front of 11,462 people at the Pittsburgh Civic Arena. Uriah Heep topped the bill, which also featured Manfred Mann's Earth Band, and the concert marked the start of what was to be a protracted period of road life for the Canadian trio. During the fall, Rush played dates with Blue Oyster Cult and Rory Gallagher, and, by the end of the year, they had sold 75,000 copies of the first album. What's more, the group had gained invaluable touring experience from that inaugural Stateside outing.

In January, 1975, Rush entered Toronto's Sound studios to start work on the second Lp. It must have been quite a relief for Alex and Geddy not to have to record spasmodically, as they had done last time. When Fly By Night came out the following month, it was clear that they had benefitted from having the time to achieve the sounds they wanted. Many regard this as the first proper Rush album and the music had certainly progressed way beyond the limitations of basic hard rock.

Fly By Night evidenced the injection of a strong fantasy element, courtesy of Neil Peart's imaginative lyrics, and "By-Tor And The Snow Dog" was the first of many epic works. The characters in the sketch had been inspired by road manager Howard "Herns" Ungerleider and the drummer's story dealt with the battle between Prince By-Tor (Geddy Lee -- "Knight of darkness, centurion of evil, devil's prince") and the good Snow Dog (Alex Lifeson). Snow Dog eventually emerged victorious and the whole number was to become an integral part of the Rush live show.

The group had clearly realized that variety was the spice of life and consequently the LP contained a diverse selection of material -- another Zeppelin influence? While the opening cut "Anthem" (the title stemmed from the book by Russian authoress Ayn Rand) proved that the trio still possessed the ability to rock hard, the delicate "Rivendell" (a village in J.R. Tolkien's Lord Of The Rings) acted in total contrast. Other good songs included "Beneath, Between and Behind", "In The End" and the title track itself. Quite simply, Fly By Night proved that Rush had far more to offer than your average run-of-the-mill heavy metal band.

The overall response to the record was most encouraging. It went gold in Canada, sold respectably in the United States and also earned the trio a Canadian Juno Award as "Best New Band." Coinciding with the Lp's release, Rush embarked on a four-month American tour, opening for the likes of Kiss and Aerosmith. Subsequently they headlined their first major Canadian dates and attracted a 4,000-strong sell-out crowd at Toronto's Massey Hall.

The summer of '75 saw the release of Rush's third album, Caress Of Steel. Unfortunately, though, it turned out to be a miserable flop. Why? Well, there are several theories. Firstly, the group had recorded the LP only a few months after completing Fly By Night and the fact that they returned to the studios so quickly may well have had adverse effect. Secondly, they continued to indulge in mammoth storylines, this time devoting an entire side to "The Fountain Of Lamneth". It was widely felt that they had stepped out of their depth and become self-indulgent.

Whatever the reasons for its commercial failure, many fans have since found Caress Of Steel to be a highly entertaining package. The first side featured three relatively short numbers -- "Bastille Day", "I Think I'm Going Bald" and "Lakeside Park" -- together with the 12 1/2 minute tale of "The Necromancer", in which Prince By-Tor was to make a brief cameo appearance. "The Fountain Of Lamneth" was a classic opus and was divided into six different parts: "In The Valley", "Didacts And Narpets", "No One At The Bridge", "Panacea", "Baccus Plateau" and finally "The Fountain" itself. There were some marvelous mood changes and the overall instrumentation was quite superb.

Be that as it may, Caress Of Steel was hardly destined to do Rush any favors and their ensuing US dates soon became tagged as the "Down the tubes tour." Things certainly weren't looking good for the band and, as they played a series of small town clubs, their momentum appeared to have been lost.

Not to be deterred, Rush returned to Toronto's Sound studios at the end of the year, where they spent the cold winter months recording a new album. In the spring of 1976, they re-emerged with 2112, which heralded the turning point in their career. The group was extremely positive about the record and as Neil Peart later remarked: "We felt at the time that we had achieved something that was really our own sound, and hopefully established ourselves as a definite entity."

Although critics had previously slammed Rush for indulging in marathon pieces, the band adhered to its principles on 2112. The whole of side one was consumed by the ambitious title track! Once again, Neil had been guided by the late Ayn Rand's literary skills and the "2112" story was centered around the struggle of freedom against oppression in a futuristic society. Under the stern dictatorship of the "Priests Of The Temples Of Syrinx", the main character finds a guitar and makes music, something unheard of in his culture-less world. He takes his discovery to the priests, but it is immediately rejected and destroyed. Rush fanatics reveled in the tale and it was to become a major highlight of the group's concert performances.

The second side of the record comprised a further five winning cuts: "A Passage To Bangkok", "The Twilight Zone", "Lessons", "Tears" and "Something For Nothing". All in all, it was a very good album.

By June '76, Rush had sold 160,000 copies of 2112 in the United States alone and had also received gold awards for the Rush and Caress Of Steel albums back home in Canada. The group's obvious penchant for science fiction/fantasy works brought them to the attention of Marvel Comics' writer David Kraft. In fact, the March '76 issue of The Defenders was dedicated to the trio and the comic's villain, Red Rajah, actually quoted from the song "The Twilight Zone".

More importantly, though, 2112 helped Rush to build heavily on a strong underground following that was growing rapidly in Britain. Despite the fact that the album wasn't actually released there until 1977, import copies began to filter through and created considerable interest among UK rock fans.

In the fall of 1976, Rush issued the live All The World's A Stage Lp, which had been recorded over three nights -- June 11, 12 and 13 -- at Toronto's Massey Hall. The double record set opened with "Bastille Day" and the rest of the first side contained "Anthem", "Fly By Night", and "In The Mood". Part two continued with "Lakeside Park" and an edited version of "2112". Side three took us back to Fly By Night days and featured "By-Tor And The Snow Dog" and "In The End". Both renditions were infinitely better than their studio counterparts and during "By-Tor" there was a lively guitar/bass battle between Alex and Geddy. The final section of "Working Man", "Finding My Way" and "What You're Doing" brought the package to an exciting climax.

Due to the lack of overdubs, All The World's A Stage had a few rough edges, but nevertheless served as an excellent live representation of Rush's music from 1974 to 1976. Indeed, as the group's sleeve notes on the back cover read: "This albums to us, signifies the end of the beginning, a milestone to mark the close of chapter one in the annals of Rush."

Following the emergence of the live album, the band set off on another session of Canadian and American dates, which saw them moving into considerably larger venues. Rush finally celebrated the end of a hugely successful year with a show at Toronto's massive Concert Bowl. Such was the demand for tickets that they were forced to add an additional performance at the venue a few days later. At these two gigs, the trio played to in excess of 15,000 fans.

It had taken eight years, but there could be no doubt that Rush had finally arrived.

In The Limelight

Eager to capitalize on the triumphs of 2112 and All The World's A Stage, Rush launched into 1977 with another full-scale American tour. Yet, although they were now able to pack out midsize venues across the nation, the band still found it impossible to gain radio airplay. Consequently, staff at Mercury Records put together a promotional album, featuring a selection of material from 2112, Fly By Night and Caress Of Steel, which they sent out to radio stations. It was amusingly titled Everything Your Listeners Ever Wanted to Hear by Rush...But You Were Afraid to Play.

Meanwhile, due to mounting interest on the other side of the Atlantic, it was soon announced that Rush would be embarking on a series of European dates in June. The British leg would take in seven cities and, as soon as tickets were made available, box offices reported lighting sales.

On June 4, 1977, Rush made their debut appearance at London's hallowed Hammersmith Odeon and the sell-out crowd witnessed a truly memorable performance. The set basically followed the running order of All The World's A Stage, with the addition of "The Necromancer" and a new number entitled "Xanadu". The audience consisted of diehard Rush addicts and few left the hall disappointed at the end of the show. Sitting in the auditorium, it was amazing to see at first had the phenomenal cult following that Rush had created in the UK and even the band was surprised.

"We thought we might have a bit of a following in Britain, having received some fan mail," states Alex. "But basically we just expected small to average crowds. When we realized how strong the fan level was, we were totally blown away."

Upon completion of the British trek, Rush played selected dates in Sweden, Germany and Holland. Soon, however, the group was back in Britain to start working on a new album at Rockfield studios in Monmouth, Wales. It marked the first time that they had recorded outside their native Canada and the different environment brought about a definite change in their musical approach.

A Farewell To Kings hit the streets in September '77 and saw the band's material becoming more complex. Geddy had started playing synthesizers and one could sense that the trio was keen to expand its overall sound. Side one commenced with the title track, a fairly concise number, and was followed by the more adventurous "Xanadu", which clocked in at well over 11 minutes on record. The second half of A Farewell To Kings boasted three shorted tunes in "Closer To The Heart", "Cinderella Man" and "Madrigal", but was dominated by the epic "Cygnus X-1". At the end of the track, the hero of the story was left plunging into a black hole on his space ship Rocinante; the group promised to conclude the tale at a future date.

After recording in the peaceful Welsh countryside, Rush had mixed the LP at London's Advision studios and upon its release they returned to North American concert halls. By November, 2112, All The World's A Stage and A Farewell To Kings had all been certified gold in the United States.

Breaking their hectic US touring schedule, Rush played 14 British dates in February '78, after which they set off on a brief European jaunt. It was during this period that Mercury decided to re-issue the first three studio albums as a triple set titled Archives. In June, the band garnered the second Juno Award, this time as "Best Group Of The Year"; they had now accrued six gold and three platinum discs in Canada.

When the Farewell To Kings tour finally came to an end, Rush immediately returned to Rockfield studios, where they spent most of the summer recording their next Lp. Hemispheres was by far the trio's most daring effort to date and took a lot longer to complete than had originally been anticipated. "It was the longest time we'd ever spent on an album," proclaims Alex. "By the time we got to Trident studios in London for the mixing, we'd been in Britain for two and a half months, one month longer than we'd expected. But the thing is that Hemispheres was a different album altogether and it headed off in various directions."

True to their word, Rush completed the "Cygnus X-1" story in the form of the marathon title track, which spanned the whole of the first side. In fact, there were only three other numbers on the rest of the LP -- "The Trees", "Circumstances" and "La Villa Strangiato". The latter, a lengthy instrumental, basically served as a showcase for Alex Lifeson's finger- picking skills and was apparently inspired by one of his nightmares!

Neil Peart came up with the lyrics for the "Hemispheres" piece after reading the book Powers Of Mind. He wrote about the division of the brain into hemispheres, with the characters Dionysis and Apollo controlling the left and right sides, respectively. Cygnus arrived on the scene as the bringer of balance.

To be blunt, the whole concept got a little out of hand and it seemed that the direction of the music had become of secondary importance. When reviewing the LP for the British weekly music journal Melody Maker, I can recall pointing out that Rush might find themselves getting into a rut if they continued producing extended works, that were definitely becoming self-indulgent. They had more than proved their capabilities as techno-rock masters, but now it was time to come back to earth again. Judging by the nature of their ensuing outputs, Rush obviously felt the same way.

Following the album's October release, Rush began a 113-date "Tour of the Hemispheres", which kept them on the road for the next eight months. By December, 1978, Hemispheres had shipped gold in the US and, in the same month, the group enjoyed three sell-out shows at Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens, smashing all previous box office records at the venue.

As usual, concerts had commenced in North America and it wasn't until April '79 that Rush traveled to Britian. The UK gigs opened with a two night stand at Newcastle City Hall and continued through to mid-May, with old Canadian friends Max Webster supporting. The next step was to Europe and finally the tour came to a close on June 4, with an appearance at the Pink Top festival in Holland. Alex Lifeson was forced to struggle through that particular show with a broken finger.

Having spent the past two summers at Rockfield studios, the band members were glad to get back home to Canada for their 1979 vacation. Up until now, they had maintained a non-stop schedule of touring and recording and, at last, they were able to take a well-earned rest before entering the studios. Rush enjoyed a six-week holiday and then re-assembled at Lakewoods Farm to start work on Permanent Waves. They wrote and rehearsed in an old farmhouse and, after a few days, rough versions of "The Spirit Of Radio", "Freewill" and "Jacob's Ladder" had been put down on cassette.

Eventually, they moved on to Sound Kitchen studios in North Toronto, to lay down proper demo tapes, and then it was back to the road. Thus, they were able to 'work in' the new tunes, before commencing the actual recording of the album. This approach was to become standard practice in the future.

"You can't really get in shape for the studio by sitting in a rehearsal studio, like you can from playing a two-hour set, with soundchecks and everything," states Alex. "Ever since Permanent Waves, we've made a point of going out for at least a couple of weeks after writing and rehearsing."

Consequently, Rush headed off to England in September '79 and played two concerts at Stafford's Bingley Hall, where they attracted over 20,000 fans, turning away thousands more. Shortly afterwards, it was back to the studios. Whenever they had previously recorded in Canada, it had been at Toronto Sound, but this time Rush chose to work at Le Studio, which is located some 20 miles north of Montreal. They were swift to take advantage of the surrounding countryside, which encompasses some 250 acres of land and a private lake, by setting up microphones out in the open to capture the sounds of nature.

The basic tracks for five numbers were laid down very quickly, and the final song was originally supposed to be a medieval epic, entitled "Sir Gawain And The Green Knight". However, after a good deal of deliberation, the band considered the topic to be somewhat out of context with the rest of the material and finally settled on "Natural Science".

Permanent Waves was mixed at London's Trident studios and hit record stores in January, 1980. Gone were the "Cecil B. DeMille proportioned" epics that had dominated the past few albums and in came shorter, more direct songs. Neil Peart's lyrical approach had also taken a different turn and, instead of basing his ideas on science fiction and fantasy works, he appeared to be dealing with more down-to-earth matters. The drummer has since claimed that he considers Permanent Waves to be "our first album that was in touch with reality. It was about people dealing with technology, instead of people dealing with some futuristic world or symbols."

The first side of the LP featured "The Spirit of Radio", "Freewill" and the slickly constructed "Jacob's Ladder". There was a strong feeling of modernization about the music and, at times, Rush came across in quite a sophisticated manner. However, they managed to retain their hard edge and had definitely rolled in the 80's with a winner. Side two comprised three tracks: "Entre Nous", "Different Strings" and the masterful "Natural Science". Permanent Waves was an extremely colorful album and it was hardly surprising that it hit the #4 position on the Billboard charts.

From January to mid-May, Rush toured America, playing multiple nights in large venues in St. Louis (3), New York (4), Milwaukee (2), Chicago (4), Seattle (2), San Francisco (2), the Los Angeles area (4), Detroit (2) and Dallas (4). It's significant to note that they actually registered a profit on the road for the first time.

Rush had definitely established themselves as a major force in the rock world and, when they went to Britain in June, 1980, they were able to sell out five nights at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. They made tapes of all the UK gigs and originally inteded to follow up Permanent Waves with their second in-concert album. However, as more fresh material emerged during their soundchecks, the band decided to go for another studio Lp.

In July, the trio went to Toronto's Phase One studios and recorded the song "Battlescar" with Max Webster, which later surfaced on the Websters' Universal Juveniles album. From there, Rush retreated to a place called Stony Lake and began pre-production of their own record. By the end of August, it was back to Phase One for demo sessions. October saw a brief American tour, during which new songs like "Tom Sawyer" and "Limelight" were previewed. Rush then returned to Le Studio, where they spent the next ten weeks recording Moving Pictures.

Released in February, 1981, the group's eighth studio output was a rather more dark, haunting package than its predecessor, both from a musical and lyrical point of view, and required a good deal of intense listening to fully appreciate. The first track, "Tom Sawyer", was co-written with Max Webster's Pye DuBois. Then came "Red Barchetta" and the instrumental "YYZ", the title of which stemmed from the code lettering on Toronto Airport luggage tags. Side two contained four songs: "Limelight", "The Camera Eye", "Witch Hunt" and "Vital Signs". The latter echoed strong hints of reggae, which no doubt surprised many Rush fans.

The "Moving Pictures" tour of the United States enabled Rush to become one of the nation's top grossing live acts. Furthermore, they were the only band to score three US platinum discs (for 2112, All The World's A Stage and Moving Pictures) in 1981. The trio also earned a Grammy nomination for "YYZ" in the "Best Rock Instrumental" category.

The American dates stretched through until mid-summer, at which point Rush headed back to the Laurentian hideaway of Le Studio to mix tapes for an upcoming live album. Exit...Stage Left finally emerged in the fall of '81, coinciding with a series of European concerts, and at the time Neil Peart stated: "Such as it is, we're all very proud of this one. Everything has improved so much since our last, somewhat uneven live effort -- that was by a different group. Once again, it's a kind of anthology album; a summation of the live highlights of our previous four studio albums and a couple of older reincarnations."

Unlike All The World's A Stage, it didn't run in the style of a complete concert performance and, rather than selecting one venue to record, Rush had assembled tapes (about 50 rolls!) from a variety of places on both sides of the Atlantic. While the first live album may hold greater atmosphere, one couldn't fault the execution of material on Exit. It kicked off with "The Spirit Of Radio", after which came "Red Barchetta" and "YYZ". The second side featured "A Passage To Bangkok", "Closer To The Heart", "Beneath, Between And Behind" and "Jacob's Ladder". "Broon's Bane", a 90-second previously unreleased acoustic passage, introduced "The Trees", but the majority of side three was consumed by a lengthy rendition of "Xanadu". Finally, affairs were brought to a close with "Freewill", "Tom Sawyer" and "La Villa Strangiato". Wisely, Rush had avoided attempting to reproduce the complete "Cygnus" saga!

Asked why the band decided to make another live Lp, Geddy explains: "I guess there were a whole lot of reasons. One was that we felt our live sound had changed so much that we figured we needed to up-date it on record. I mean, All The World's A Stage was a whole lot different. But doing a live record is also a great device to get a sort of hiatus between albums and we really wanted that. We wanted to have a longer gap before going back in the studio so that we could do some writing on our own."

Mind you, Geddy isn't particularly fond of in-concert recordings and openly admits that he finds them a tedious exercise. "They're sort of historical and very painful to do because there's nothing really creative about them," he reasons. "You play the gigs and invariably whenever you're recording you stiffen up and it's not the same. I hate doing them and in some ways I'm almost sorry we did Exit.

Alex Lifeson seems to share the bass player's views and, when talking to American rock writer, John Stix, he declared: "Live albums are always a difficult thing. It's hard to get excited about them. In terms of a live recording, Exit is very good and I'm happy with it in that respect. As an example of our show, it's not as good as it could have been or possible should have been. Live albums give us some breathing space to cleanse ourselves and start on something fresh and new. When we were in the studio doing Exit, Geddy and I were in another studio working on "Digital Man" and "Subdivisions" from Signals. We were already geared up for another record. I think that had something to do with the fact that we don't go crazy over live records. I don't know if you'll ever hear another live album from Rush. We enjoy the studio recordings much more than we do the live ones."

And so, Exit...Stage Left closed another chapter in the Rush history. Since the release of All The World's A Stage, the band's popularity had grown by leaps and bounds. Happily, they had been able to maintain success without compromise and as the liner notes of Exit stated: "For reasons beyond our comprehension, we have become increasingly more popular, and hence stretched ever more thinly among even more people. If sometimes we can't give the time they deserve, to our friends and loved ones, we hope they will understand and forgive us. After all, we didn't change, everybody else did!"

Graceful Under Pressure

Although Rush had been extremely proud of Moving Pictures, they were determined to explore fresh territories next time around. According to Geddy Lee: "Recording became semi-automatic with that album; while it was difficult to make, we could achieve that sound real easy. And what we got was a sound that almost bordered on being slick, which is kind of dangerous for a band like us."

Evidently, there was to be a good deal of change on the ensuing Lp, for which the trio had started writing songs during the mixing sessions of Exit...Stage Left. The lengthy gap between studio albums allowed them the longest period they had ever had to assemble new material. Upon returning from the European leg of their 1981-82 tour dates, the individual band members went their separate ways and subsequently began writing alone, something they'd never done before.

"It was interesting because we'd usually go up north and hide away for a month or so when we started writing," said Alex. "This time, because we had the break, we worked more on our own. Geddy and I both have studios at home and we were in those for quite a while. We also had the tapes of soundchecks we'd been recording over the last tour, so we could sift through them and piece bits together. In the end, we had a lot to choose from, which had never really been the case in the past. And that allowed us to be a little more critical about what was being written.

"Previously, we'd tended to come across an idea, start working on it, thinking it was great, and then a few months later find ourselves feeling that it could have been a little better. This time we could pick and choose, combining two or three different ideas into one. I think it's a direction we'll follow -- doing more basic homework."

While this approach to songwriting has enabled Rush to be more selective in their final choice of material, one wonders whether it might lead to any frustration with certain compositions not being used.

"No, that's never been the case," claims Lifeson. "We're kind of lucky because it's a three-piece band and Geddy and I write most of the music. He and I work really well together and now, when the two of us write, we bounce off each other more than we ever did before. It's a lot more objective and you can look at what you've done and be honest and say 'That's really not that very good -- it doesn't suit that piece.' So there's never a problem with material being left out."

The pre-production stage for Signals lasted until the spring of 1982, at which point Rush went back on tour, playing a two-week series of dates in Texas. Although these gigs proved successful in enabling them to run through some of the new songs, by far the highlight, as far and the band was concerned, was a trip to Cape Kennedy, Florida, to watch the launching of the Columbia space shuttle.

"It was an incredible thing to witness," Neil Peart reflects, "truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience." The event actually inspired the drummer to write the tune "Countdown".

By the third week in April, Rush were back at Le Studio, where they remained until July 15. "We wanted to finish by the middle of June," explains Alex, "and we ended up losing a month of our holiday by carrying it through. That was a sacrifice, believe me! The reason it took us longer was because it was a whole different approach for us, both in the recording and the mixing stages. In the past, things were a lot different.

"Moving Pictures, for instance, was a very lush, full-sounding Lp, where the guitars were double, triple and even quadruple tracked. But with Signals we wanted to get a more angular sound, where everything had its place and there was a little more perspective to all the instruments. The focus was not so much on the guitar being 'here' and the drums being 'there' -- it was a little more spread out in different percentages. So that took a bit of experimenting, which in turn meant more time in the studio."

Rush released the Signals album in September, 1982, and, once again, it was far removed from anything they'd done before. Reggae/ska rhythms predominated, with keyboards and synthesizers taking a more prominent role. "Basically we didn't want to go in and make another Moving Pictures," Geddy asserts, "because that's kind of against everything we've ever done. So we made a conscious effort not to play it safe and try to experiment in order to change our sound. It was time to inject some fresh blood."

For the first time since Fly By Night, Rush had succeeded in delivering eight tracks on an album, the first of which was "Subdivisions". The rest of side one comprised: "The Analog Kid", "Chemistry" and "Digital Man". Side two opened with "The Weapon", the second section of a trilogy entitled "Fear" -- part three had emerged in the form of "Witch Hunt" on the last Lp. Then came "New World Man", "Losing It", on which Ben Mink from the Canadian band FM played violin, and finally "Countdown".

"New World Man" immediately garnered strong radio airplay, but Geddy reveals: "It wouldn't have been on the record if we didn't have four minutes space available. We tend to have pretty strict ideas on how long an album should be and basically it's just a matter of value. Our shortest albums are about 18 minutes a side and that's a pretty good value. I couldn't see us going below that; it doesn't make sense to me. But, at the same time, we're now recording digitally and so we do have certain considerations as to how the whole thing's going to sound when you cut it. There, you're dealing with quality, which is again down to value for money."

Aside from filling an open space, there was also another important factor behind the inclusion of "New World Man". Says Geddy: "I think what it really boiled down to was that we'd worked so hard getting all these slick sounds that we were all in the mood to put something down that was real spontaneous. In the end, the whole song took one day to write and record. It's good to put something together like that."

Signals saw the band employing long-serving producer Terry Brown (affectionately known to the group as "Broon"), with whom they had actually worked on every LP since the debut Rush album. Asking Geddy why they had continued to stick with him so rigidly, he theorized: "I guess it's because we've built up such a great relationship. We're not the kind of band that can have a 'producer'-type producer because we're very aware of what we want to do, and we're also very stubborn in that respect. I don't think we'd get on with the kind of guy who tries to be dictatorial; it just wouldn't work. We have to work with somebody who's flexible and whose opinion we respect.

"Terry Brown fits that category and we have very high regard for his objectivity and creativity behind the desk. One day we might decide to go for a change, but if we did it wouldn't be through any lack of respect for Terry. It would merely be a case of time and change. But I really don't know if that'll ever happen."

(As time would tell, that change was to come a good deal sooner than either Rush or Terry Brown expected.)

Throughout the group's recording history, their albums have always been presented with elaborate sleeve designs. The cover for Signals, however, was particularly bizarre. The photograph on the front featured a dog sniffing around a fire hydrant, while the back contained a map of an imaginary secondary school, named after Montreal Expo slugger Warren Cromartie. The whole concept was down to Hugh Syme, whose initial involvement with Rush stretches back to 1975, when he provided the graphics for Caress Of Steel. He has subsequently contributed his artistic talents to the entire Rush catalogue, as well as the design of their tour books. He has also earned keyboard credits on songs like "Tears" and "Different Strings".

In an effort to explain the Signals sleeve, Geddy states: "Well, we wanted the album to sound different and we also thought that the packaging should have a different feel. When we were talking about Signals, Hugh had this concept of taking the idea down to a basic human level -- territorial or even sexual. So that's how the design with the dog and the fire hydrant came about. The little map on the back features make believe subdivisions, with a lot of silly names and places. The red dots represent all the fire hydrants and basically the whole thing maps out a series of territories."

In the same week that Signals reached record stores, Rush embarked on a marathon Stateside trek. I was fortunate enough to team up with the group in Omaha, Nebraska (well, kind of fortunate!) to catch one of the early dates of the tour. It was my first opportunity to see the band in the Mid-West, a noted Rush stronghold, and I witnessed a memorable performance.

The show got underway with a vibrant rendition of "The Spirit Of Radio", which was followed by "Tom Sawyer" and "Freewill". Geddy then announced that the new record was in the shops and that most of it would be aired tonight. He did not lie and, aside from "Losing It", the trio performed the entire album. Best of the new bunch were "The Weapon", "Chemistry" and "Subdivisions", all of which were enhanced by clever celluloid accompaniment.

In recent years, Rush have employed quite a few films during their gigs and according to Geddy: "The basic reason we've got into using them more and more is that there are a lot of times now that the band is trapped behind gear and sometimes there's not a whole load of action from us. So it helps to add more visuals to keep the people interested."

The rest of the Omaha concert comprised material from Moving Pictures as well as the odd tune from Permanent Waves, together with "The Trees" and "Closer To The Heart". Old songs were confined to a medley at the end of the set, which featured "2112", "Xanadu", "La Villa Strangiato" and "In The Mood". All four were edited versions, but ran into each other extremely well. The sole encore piece was "YYZ". Overall, it was an extremely entertaining show that flowed smoothly without leading to tedium at any point.

"This set is paced well," declared a relaxed Alex Lifeson, as we chatted after the concert. "In fact, I think it's the best set we've ever done. It's a bit early to say, since we haven't been out that long, but the pacing is very 'up' and it doesn't seem to let down at all."

While agreeing with Alex, I could also envisage that a lot of Rush fans might be disappointed that there wasn't more older material. How did he feel about that?

"Well I can sympathize with people who want to hear us do more old stuff, but there is a limit to what you can actually play during a two- hour set. Nowadays, we want to play a lot more of the newer material from Permanent Waves on and it feels good doing the fresher tunes. To me, things are moving along much better now that some of the older, longer pieces aren't there anymore. Also the show itself has a totally different feel to it. The band has a different appearance, the sound has taken a step forward, everything is much fresher and, to tell you the truth, I feel really good -- almost re-born."

The "New World Tour" of the North American continent saw Rush playing to in excess of a million fans and, by the beginning of 1983, Signals had been certified platinum, both in Canada and the US. In May, the band flew to Europe, however Geddy told me that he now had mixed feelings about playing in Britain.

"I like it and I don't," he mused. "When we first went over, I really liked it a lot and I still enjoy playing certain places. But I find it a real grind. Sometimes, it seems that you can do no right in the UK. For example, every tour we've done has been pretty extensive for a North American band. We've played in a lot of the smaller towns and done multiple days in them because we've wanted to. We appreciate the fact that those kids have supported us. But, while that was going on, we got complaints that we weren't playing enough gigs because more people wanted to see us. So what do you do?

"We figured that if more people want to see us, then we'll play the bigger halls, although I didn't know all these UK halls are as bad as they are. (NB: The larger British venues have very poor acoustics.) We played three nights at Wembley, Bingley and Scotland, and still got complaints! I really felt hurt because it seems that you just can't win. What do you have to do to make people happy? Because of that 'no-win' situation, it's taken a bit of the edge off playing there."

Despite this apprehension towards British gigs, the UK shows turned out to be another unqualified success and climaxed with four consecutive sell-out concerts at London's 10,000-seat Wembley Arena.

Meanwhile, after Geddy's gushing praise for producer Terry Brown when Signals had come out, it was somewhat ironic that, during the final stages of the 1982-83 tour, the band decided to work with someone else on the next album. In no way dissatisfied with "Broon", they simply felt the need to seek fresh creative input. As a result, during the English dates, Rush met with various esteemed producers before reaching a unanimous decision that Steve Lillywhite, of Big Country, Simple Minds and U2 fame, was their man. It wasn't long, however, before a call came through from Lillywhite's manager, relaying the message that he didn't feel he was quite right for the job.

Rejected by the new wave, the group was forced to start basic pre- production unassisted. In September '83, their schedule was disrupted by a five-night stand at New York's Radio City Music Hall, which had originally been intended as a warm-up for the final recording sessions.

Months slipped by and, towards the end of the year, it began to look as though Rush might have to produce the entire album themselves. Fortunately, their quest for the "right man" finally ended, when they hooked up with former Supertramp producer Pete Henderson. Completing the LP still proved something of a nightmare and Alex told the Milwaukee Journal: "It was kind of like childbirth, but instead of 20 hours, it was six months of non- stop labor. It was difficult and took a long, long time to finish."

By March, 1984, the album was ready to be mastered and the band had come up with the appropriate title, Grace Under Pressure. In his highly illuminating "Pressure Release", Neil Peart wrote: "Our records tend to follow in cycles, some of them exploratory and experimental, others more cohesive and definitive. I think that this one, like Moving Pictures, Hemispheres or 2112 before it, is a definitive one of its type. Really, it defines its type. An indefinable thread, both musical and conceptual, emerges in a natural way and links the diverse influences and approaches into an overall integrity."

The protracted studio stint had certainly proven worthwhile and, in Grace Under Pressure, Rush delivered a near perfect album. While the white-reggae flavor lingered on, there was a sense of urgency to the songs, something that Signals had lacked. Side one comprised: the first US single, "Distant Early Warning", "Afterimage", "Red Sector A" and "The Enemy Within", the first part of the "Fear" trilogy. (Strange how they undertook this project in reverse!) The second side boasted "The Body Electric", "Kid Gloves", "Red Lenses" and "Between The Wheels".

No longer buried beneath a mass of keyboards and synthesizers, Alex Lifeson's guitar playing took a more up-front position in the mix. Talking with Guitar magazine, he observed: "That's exactly what we were going for. In retrospect, Signals tried to achieve a focus on the keyboards. We wanted the guitar to become part of the rhythm. I enjoy rhythm guitar very much and try to make the most of that genre. Unfortunately, somewhere along the line we lost it. On Signals we wanted to change things and, unfortunately, the guitar took a back seat. When we started on this new album we wanted to bring the guitar back into the forefront and strike the proper balance between all the elements."

Although the music was a good deal brighter, Neil Peart's lyrics appeared somewhat doom-laden and nuclear war, acid rain and technology were among the concerns expressed. The drummer had evidently been influenced by current news events and, in his "Pressure Release", he revealed that, during the writing stage, he would read the Toronto Globe And Mail over breakfast before starting work on his lyrics. "The topics of the day, especially as expressed in the editorials and letters to the editor, were necessarily on my mind," he admits, "and this circumstance affected the lyrics to certain songs profoundly."

Tying in with the LP title, the inner sleeve depicted an egg, held within the menacing jaws of a metal C-clamp. "The important thing is not to crack," said Neil to one reporter. Once again, the front cover artwork was designed by Hugh Syme, but the back sleeve photograph was taken by the 75- year old internationally renowned portrait lensman, Yousuf Karsh. The photo session took place in an Ottawa hotel room and, despite Karsh's impressive track record with royalty, presidents, astronauts and film stars, the end result was generally considered an extremely unflattering photograph of the band. However, Geddy told a critic from the St. Paul Pioneer Press: "I think the picture brings out our personalities quite nicely. But it also looks like a bar mitzvah photo, doesn't it?"

When Grace Under Pressure was released in April '84, record stores immediately reported strong sales. In the meantime, Rush had gone over to Britain to shoot videos for "Distant Early Warning", "Afterimage", "The Body Electric" and "The Enemy Within" using directors Tim Pope, David Mallet and Cucumber Productions. On returning to America, they hit the road for the first section of a two-leg US tour.

The onset of full-scale success has allowed Rush the freedom to pace road activity to suit their own desires. Rather than spending month after month living out of suitcases, their touring sprees are now limited to no more than two or three months at a time, with a steady balance of days-off in between shows. Aside from avoiding having to spend lengthy periods away from their families, it also prevents the stage performances from becoming stale.

"Touring eventually takes its toll," reckons Alex. "After three months you begin feeling run-down and can end up doing shows that you don't really enjoy. Sometimes you find yourself sitting in a dressing room before going on stage and all you really want to do is sleep or go and vegetate in front of the TV."

Asking the guitarist whether attaining their current high-ranking status has helped alleviate some of the pressure, he replies: "The pressure is different now. It's greater in some respects and less in others. We don't have to play nine days in a row anymore, with one day off in between. But, at the same time, the show has grown a lot since those days and there's a little more responsibility inherent in that. But, if you stay on top of things then it never gets to the point where it's a major concern. And if, by any chance, it does, then it's easily dealt with because everybody's basically on the same level."

A lot of water has passed under the bridge since the early days in Toronto and certainly Rush never envisaged that they would end up scaling the dizzy heights of mega stardom.

"I think every young musician can relate to this; you have this sort of dream about 'making it', but don't really know what that means," says Geddy. "You just go for this blind goal with your eyes closed, your heart wide open and let things happen from there. You've no idea what you're going for and what it'll be like when you get there. I don't think any of us realized how far Rush would go and I don't think we like to think about it either."

Who knows what the future holds in store for the band? During the 1984 tour dates, rumors began to circulate that a split might be in the air, but, then again, such gossip is inevitable with any group that has been around for so long. However, in his interview with the Milwaukee Journal, Alex did comment: "I really, really doubt if we'll be touring like this when we're 40 years old. I've got two boys, 13 and 7, and being on the road gets to be a grind."

In Rock Magazine, Geddy declared: "It's hard to say how long we'll stay together at this. There's a lot of things we'd like to do in the future, but if the three of us aren't happy and excited by what we're doing I don't see us hanging around."

Lee also told the Pittsburgh Press: "It's getting to the point now where you start thinking about going on to other things, but somehow you come back to this. The tours are getting shorter every year. It seems more difficult to stay on the road each year. There's so much else to life that you want to live and do."

Whether Rush will actually call it a day in the near future seems unlikely, since the three members still derive a tremendous amount of pleasure and satisfaction from working together. One would imagine that they will simply attempt to maintain a comfortable balance between group activities and outside pursuits.

We shall see.