Grand Designs For The Future

After Talk Of A Breakup, The Canadian Trio's Vital Signs Look Good

By Philip Bashe, International Musician And Recording World, December 1985, transcribed by pwrwindows

Having just completed an album after four grueling months in the recording studio with nary a break, Rush's Geddy Lee is ecstatic. But it's not the new Power Windows that has him so tickled. At the moment the group's bassist/keyboardist is more concerned with hits on a baseball diamond than on the LP chart, as he tracks the progress of his beloved Toronto Blue jays, who are on the verge of capturing the American League Eastern Division crown in the waning days of the pennant race.

"You'll never know how good it feels," he smiles blissfully while fingering a plastic infielder's-mitt keychain. We're sitting in an office in Rush's headquarters, located in a four-story brick building in Toronto's Cabbagetown section. lf it weren't for the sundry gold and platinum albums adorning the walls, and the several Juno awards earned by the trio over the years, you might confuse this with a shrine to Canada's almost-national-pastime. Over there is a box brimming with unopened demo tapes, but hung conspicuously on the wall is an autographed photo of Dave Stieb, the Blue Jay's ace right-hander. And over in the corner is a seven-foot-tall cathode-ray tube-sent to the band as a joke gift-but a mitt and a ball rest on the window ledge, and two bats also hang on the wall.

Lee, dressed casually on this unseasonably warm day, adjusts his sunglasses. "They lost last night, so I was a little bit melancholy," he sighs. "I've noticed that my moods are definitely tied to the won-loss column."

Lee's moods are similarly affected by his band's most recently completed albums. He had some reservations about 1982's Signals, on which the group shifted toward a more keyboard-heavy direction. And 1984's Grace Under Pressure-the second in a trilogy from a band that's gone through more cycles than an automatic washer-left him with mixed feelings, its songs, he says in retrospect, underdeveloped. After 12 albums, the last 11 of which were recorded by the lineup of Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart (sounds like a potent double-play combination), Lee mused to one reporter that perhaps Rush had peaked, and that for the first time the group's demise was a clear-cut possibility.

That view was seconded by Peart as he was toweling off backstage at Madison Square Garden last fall. It was pretty incongruous: a band contemplating retirement after having just played an electrifying two-hours-plus show before a fired-up soldout crowd of nearly 20,000. Perhaps the band felt that having mastered its instruments years before, there was little room for development.

But there was. Though they'd always employed advanced recording techniques-utilizing 48 tracks at Quebec's Le Studio and using digital technology as far back as 1981's Moving Pictures-Rush were always self-governed by what Lifeson calls their "golden rule of not doing anything in the studio that we couldn't do live." That method of recording was antiquated by 1985 standards, where bands often assemble hit records under the direction of producers and engineers, and then first learn how to play together, or how to play, period.

For Power Windows, says Lee, "We decided not to hold anything back. We wanted to develop the songs to their fullest, so for the first time we just said, 'Let's make the record and worry about the live show later.'" The result is some novel techniques, such as the inclusion of double-tracked vocal harmonies from Lee, at the suggestion of producer Peter Collins.

A slight, bearded 34-year-old from Redding, England, Collins encountered only occasional resistance from the band, which specifically selected him for his capabilities in the area of arranging. Currently producing Billy Squier, Collins boasts a diverse list of credits, including Nik Kershaw, Musical Youth, Match-box and Air Supply. "Now, whoever thought," Alex Lifeson chuckles, "that Rush would be produced by the same guy who did Air Supply?"

At a stage in their career where, for most bands, self-production is almost a given, Rush actively sought a producer from whom they could learn, indicative of the musical inquisitiveness that has been the cornerstone of their ability to progress steadily over the years. And Collins is a meticulous producer in the conventional sense of the word, unraveling songs and examining their construction and melodic and rhythmic content, "and then maximizing all those elements," while ruling over the sessions. "My say is always going to be final," he says offhandedly.

Rush, determined to ward off creative atrophy, welcomed Collins's input, as it represented a refreshing reversal from what transpired with producer Peter Henderson during the making of Grace Under Pressure. That record was the first of the band's career without producer Terry Brown, and Rush were forced to settle on Henderson after a number of name producers-including Steve Lillywhite-pulled out of or simply turned down the project. Henderson, says the soft-spoken Lee, was more of an engineer ("and quite a good one") than an actual producer, as are, he feels, "about eighty-five percent of the producers out there today." It's not a healthy trend, he goes on to say with a trace of annoyance. "That's why there are so few really strong contemporary songwriters, because they're not being developed by song people, they're making records with engineers."

Collins's arranging expertise was one factor in Rush's newfound adventurousness on record. A contributing factor was the knowledge that with the advent of sound-sampling technology and increasingly sophisticated synthesizers, almost any sound-such as the real strings and choir on side one's "Marathon" -can be reproduced live. For the group's upcoming tour, scheduled to begin this month, the only problem forseen by guitarist Lifeson is "getting ourselves really familiar and comfortable with all the extra things our feet are going to be doing."

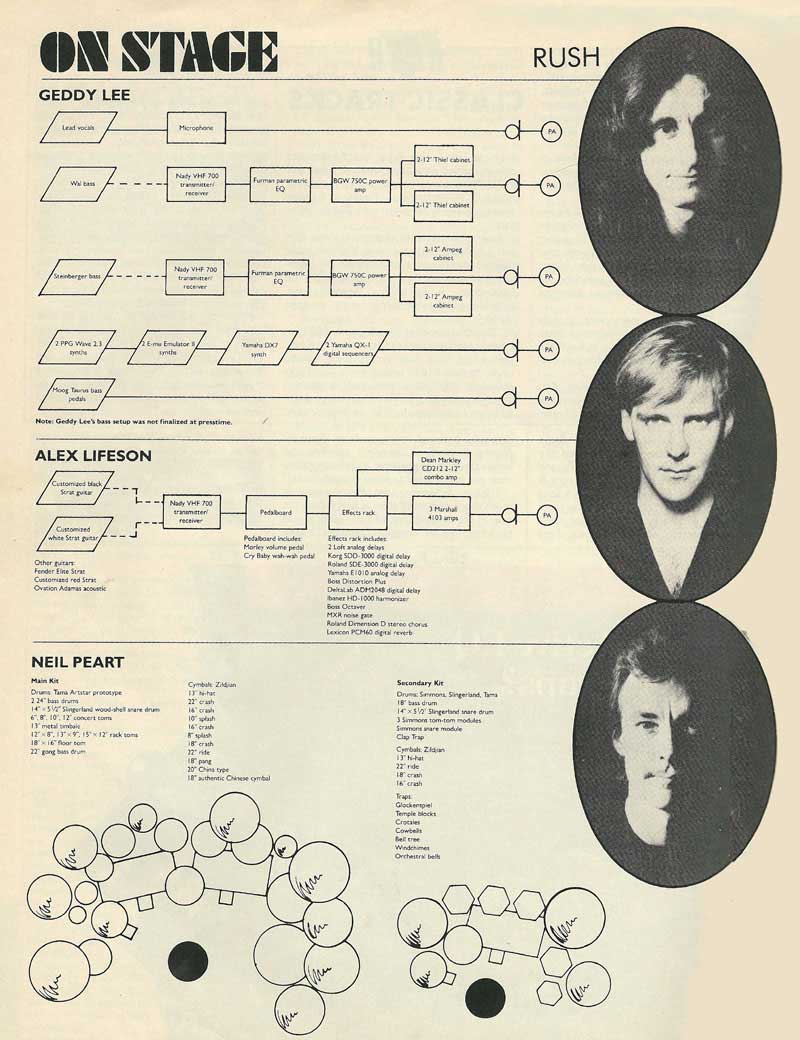

As it is, Rush busy themselves on stage with enough pedals to confound a group double their size. Lee generally stations himself rigidly at the mike stand, hands roving his bass while his feet sound out sonorous notes on his Moog Taurus bass pedals. Or he sings from a small sanctum of keyboards: for this tour, two PPG Wave 2.3 synths, two E-mu Emulator II sampling key-boards, two Yamaha QX-I digital sequencers and a Yamaha DX7 synth. Lifeson is likewise engrossed on stage right, while Peart fortresses himself behind 13 drums, 10 cymbals and numerous traps; you have a better chance of sighting a UFO than you do of the drummer during a show. Lifeson, who with his open, friendly face and stylish blond hair is Rush's closest thing to a matinee idol, remarks regretfully that their myriad duties live preclude the type of stage show one usually expects at a rock concert, though Rush do enhance theirs with an exceptionally inventive film and light show. It's either that or carry along additional musicians, and of all their achievements, Rush are probably proudest of the fact that their music has always been the work of just three pairs of hands.

Until now. Thanks again to Peter Collins, with Power Windows another rule was shattered, as nearly all of the songs include keyboard embellishments from Andy Richards, who'd worked with Collins previously and with Trevor Horn. "I was really nervous at first," admits Lee. "I thought, 'What's going to happen? Is he going to turn us into a new band?'"

But Richards, whose specialty is programming sequencers, won Rush's respect within a matter of hours. "He can program a bass part faster than you could ever play it," marvels Peart, adding that rather than feeling threatened, the group enjoyed "being able to sit back and produce somebody else on our music for a change."

Richards' setup consisted of a PPG Wave 2.3 synth MIDI'd to a Roland Super Jupiter synth module and a Yamaha QX-1 digital sequencer, as well as Roland Jupiter-8 and Yamaha DX7 synths. The orchestral section that opens the new album's "Grand Designs" is Richards on the 2.3, which is also the source for the clangorous figure on "Territories"'s third verse: a brass sample that's sequenced to Lifeson's guitar, fades out and returns as a clavinet sound.

Having so many keyboard sounds and tonal possibilities at one's disposal, however, can be as exasperating as it is liberating. Says Lee: "You have to be very organized and decisive when recording keyboards these days, or else you could sit there forever. 'What about this sound?'

"After a while," he continues, "you can't hear anything anymore, just digital noise, and it can be very frustrating. I think that you constantly have to go back to the song and ask yourself what you're looking for. Are you just jerking off-looking for a sound for the sake of a sound-or does the part really require it? That's the hallmark of a good producer, someone who remembers that and keeps bringing you back to the song."

On Power Windows, like Richards, Lee mostly relied on the PPG Wave 2.3, as well as the Jupiter-8, the Yamaha DX7 and an Oberheim OBX-a. Of the Wave 2.3, he says praisingly, "It doesn't sound like any other instrument. Plus, it really holds its own when you're recording, unlike, say, the DX7, which requires a lot of work to get it to retain its character once you put it on the track. It gets crushed easily, which the PPG doesn't."

He continues to use the venerable Moog minimoog, which, not counting his Taurus pedals, was the first synthesizer Lee ever purchased, nearly 10 years ago.

"It's still the ultimate triumph of form and content, like the six-and-a-half-ounce Coke," he says, laughing. "It has a lot of body-that's the main thing-and it's so simple to operate."

Lee's and Richards's keyboards dominate several of Power Windows' tracks, as per the concept first implemented on Signals. At the time, that presented something of a problem for Alex Lifeson, who saw his own instrument's role diminish-ironic in light of his initial enthusiasm for the new musical direction.

Lifeson concedes that he felt frustrated during the recording of Signals, and Lee says ruefully that the band consequently felt compelled to compensate on Grace, at times "enlarging the guitar's role even when it didn't really fit." On Power Windows, asserts Neil Peart, there's a better "time share" among the instruments, and Lifeson benefits not only from having more space but from the broad, incandescent sound achieved for him by engineer James Barton. His chordal parts, as on the album-opening "The Big Money," shimmer, and his solos blaze. After spending five weeks recording rhythm tracks, keyboards and bass at the Manor, in rural England (on two Studer A800 24-tracks slaved together and an SSL console), Rush, Collins and Barton flew to Montserrat's Air Studios for Lifeson's parts, using the two Studers in conjunction with a vintage Neve desk. (Vocals and mixing took place at Sarm East Studios in London, on Studer ASOO and A80 multitracks, an SSL console and a Sony PCM-1610 digital recorder.)

Recording the guitarist, says Collins, was painstaking work, requiring experimentation with various combinations of microphones and amps, as Lifeson had with him four Marshall 410 2-12" combos (with the built-in reverb disconnected); a Roland JC-120; a Dean Markley CD212, a 120-watt tube amp with two 12" Magnum speakers; and a Markley Spectra I 112A, a 20-watt model with one 10" speaker and switchable overdrive. Lifeson, who over the years has played through Traynors ("with Norelco speakers that sounded like Norelco razors"), BGXs, Marshalls, Hiwatts and then Marshalls again, is particularly delighted with the Dean Markleys' versatility. For solos he used the Spectra 112A, a Rockman, a Gallien-Krueger 250ML (speakers off) and two of the Marshall twin-12" combos, adding only slight changes in equalization through the console.

Effects were Loft analog delay "for chorus," Korg SDD-3000 and Roland SDE-3000 digital delays, Yamaha E1010 analog delay, Boss Distortion pedal, DeltaLab ADM2048 digital delay and Ibanez HD-1000 harmonizer. Lifeson used the latter for the exotic, sitarlike lines on "Territories," "one octave up, with a little bit of modulation for that oriental sound."

That was played on the most recent addition to Lifeson's cache of instruments, a Fender Elite Strat, of which he says, "It's the first guitar I've ever tried that had great sound, action and intonation and felt perfect right out of the case." Customizing is done by Ted Venneman of Venneman Music in Arlington, Virginia, who greatly modified Lifeson's red, white and black Stratocasters. All have necks made by an Ottawa, Canada, company called Shark; two stock pickups and one Bill Lawrence L-500; original Floyd Rose tremolos; and all have had the controls and switches altered for easier access.

The red Strat is preferable for lead work, claims Lifeson, describing its sound as "thick and bright, with a lot of sustain." He employs it live on songs such as "The Big Money" and "Middletown Dreams" from the new album. The white Strat, which is strapped on for songs such as "Tom Sawyer," "The Spirit of Radio" and "The Body Electric," has a cleaner sound with less sustain, and is additionally customized, the headstock bearing the logo "Hentor Sportocaster." Lifeson explains:

"lt was a nickname that we had for Peter Henderson while we were recording Grace Under Pressure-'Hentor.' I don't think we called him by his real name more than twice during the sessions, and 'Hentor' eventually evolved into 'Hentor the Barbarian.' So, I bought some press-type lettering and named the guitar accordingly."

Finally, there's the black Strat-Lifeson's main model-which is used for the bulk of the live set and has a rich, full-bodied tone. Lifeson, whose first guitar was a Kent classical purchased for just $12, uses Dean Markley strings (.009, .011, .014, .028, .038 and .048) and wields Kay nylon picks, which are manufactured in Wales and "are really hard to get."

Despite his acclaim as one of the top drummers of his generation, Neil Peart has, unexplicably, found it just as hard to get his recorded drum sound to match his talent-one of the first criticisms producer Collins raised to the group after watching it perform for the first time, in Providence, Rhode Island. "I told them that I thought Neil's drums always sounded a bit lifeless," says Collins, adding with a rare grin, "and that if they hired me, I guaranteed them a much better drum sound."

Collins delivered, though much of the credit has to go to both Peart's keen tuning abilities and his resonant Tama Artstar prototype kit, which he had custom built with thinner shells, conferring with company president Ken Hoshino. His rosewood-finish set was recorded in the Manor's stone room, and Collins says that once the initial drum sounds were established, recording Peart's parts ranked among the simplest aspects of producing Power Windows.

Peart, whose imagination is boundless, is particularly proud of the drumming on the LP closer, "Mystic Rhythms," for which no snare drum was set up. He and roadie Larry Allen drove to a percussion-rental shop in London, "filled up our station wagon with all of these African and Indian drums," sampled the sounds into an AMS digital delay unit and triggered them by way of Peart's Simmons SDS7 electronic drums. The resultant, unorthodox kit consisted of high- and low-pitched tablas, a talking drum, and "this giant Burundi tribal drum that we'd sampled, with me hitting it with a mallet as hard as I could."

It's a consequence of modern recording practices that many listeners will probably assume that the dexterous drumming on "Territories," to cite one example, is the handiwork of a drum computer. But there are no drum machines used on Power Windows, and precious few overdubs for the percussion tracks.

About the only "cheating" is a sung drum sound on "The Big Money" and "Territories," for which Peart sampled his own vocal impression of a drum and then triggered that with his SDS7. The tall, rangy drummer also recently acquired a Simmons SDSEPB digital EPROM blower, compatible with the SDS7, for making his own chip sounds.

On the 1984-85 tour, Peart played the Artstar prototype and a scaled-down Simmons kit with a Slingerland snare and Zildjian cymbals, the only brand Peart has ever used. He expects to take the same setup and the same revolving drum riser out again this year. Peart crowns his acoustics with Evans heads live "because they stay in tune and last for a long time," while in the studio he chooses Remo Pinstripes for their similarity in sound to the Evans's, "only they don't take as long to break in." His Slingerland snare takes a Remo Black Dot, which generally lasts, he estimates, about one week.

Peart, who doubles as Rush's lyricist, is responsible for Power Windows being the group's first concept LP about the various manifestations of power, from personal to global. The 33-year-old Peart is a modest but forthright intellectual (A cerebral drummer? Isn't that like an honest politician?), whose curiosity extends to subject matters rarely within the realm of most rock & roll songs. And he's not afraid to go out on a limb, as on the new record's "Manhattan Project," which takes the unpopular viewpoint that the scientists involved in the creation of the atomic bomb during World War II are deserving of compassion and were not necessarily monsters in white lab coats. One can imagine Sting wincing at the lyrics to this one, but it must be said in Peart's behalf that he does his homework before undertaking a historical subject. Prior to penning "Manhattan Project" during "writing camp"-in a pastoral Canadian farm town called Elora-he read several books on the subject. As on other such songs ("Beneath, Between & Behind" from Fly by Night), Peart studiously avoids the type of historical revisionism most rock & roll songwriters are guilty of. (After all, who's going to run to an encyclopedia to check?)

For Lee, who as the band's singer must voice Peart's thoughts, agreement on the lyrics is essential, and he, Peart and Lifeson frequently discuss potential topics: How they will be treated, as well as if they can be essayed effectively in a rock & roll song, which, Lee contends, isn't always possible. "lt's hard to bring up certain subjects without it coming out very dry, like a thesis," he says. "Like 'Countdown,' from SignaIs," about the launching of the Space Shuttle. "That was an interesting topic, but the song itself was horrible; an absolute failure."

Rush songs tend to pertain to Big Concepts. Surely if someone checked, Peart would be a candidate for entry into the Guinness Book of World Records: 12 LPs, and not one dreamy love song or ode to rock & roll among them. And just as rare is a song that sheds some light on the band-members themselves, who are notorious for their zealous protection of their privacy. Even atypically personal lyrics, such as those to Moving Pictures' "Limelight," concern the band's struggle to preserve its privacy: "One must put up barriers to keep oneself intact."

Lifeson, however, sees Peart revealing much more of himself than at first meets the eye. "I see an awful lot of him-and us-in his lyrics, like on 'Emotion Detector.' We're all in there, but Neil puts it in more universal terms, so that it doesn't seem too personally reflective."

The most recurrent Peart theme is individualism, which resurfaces on several of Power Windows' tracks, such as "Grand Designs," "Marathon" and "Territories." Asked what makes it the basis for so much of his writing, Peart reflects on his years spent growing up near Hamilton, Canada, which he describes as "very conformist. The high school I went to had only three guys with long hair and weird clothes and who were into rock music." Peart was one of the three, "and the jocks would hang around the radiator, laughing at us weirdos. It was individuality versus conformity.

"Plus, there was the additional social pressure from wanting to be a musician. It gave me very much a me-against-the-world kind of feeling."

Growing up in Toronto, schoolmates Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson shared the same feelings, which is why a song such as Signals' "Subdivisions"-with its line "in the high-school halls, conform or be cast out"-has special meaning for the band. So does a verse to a new Peart lyric, "Middletown Dreams," about a youth who yearns to grab his guitar case, climb aboard a bus and make his bid for stardom. "I thought," Lee says kiddingly, "he should have hopped on the bus with a drum machine and a sequencer.

"But I was very much like that kid," he continues, "That's all I ever thought of doing. At school I was a daydreamer-if you saw my report cards from back then, they'd all say, 'Daydreams too much, doesn't pay attention.'"

Lee and Lifeson met 17 years ago, when they were both 15, in the same ninth-grade class at Fisherville junior High School. "We used to jam together," recalls Lifeson, who was playing a $59 Conora, and before that strummed a pool cue along to Beatles records, "Usually we did it at his place, because Ged had an amp and I didn't. So we'd both plug into his amp and play mostly Cream songs: 'Spoonful,' and Jimi Hendrix's 'Purple Haze.'"

Neither received too much support from his parents, especially Lee. His father had died when he was young, and his immigrant mother "didn't understand what the hell I was doing," playing with Lifeson and drummer John Rutsey, a neighbor. The turning point for both came when their parents saw them on television for the first time. "They saw that," laughs Lifeson, "and figured, 'Oh, it's O.K. He's got a job.'"

After recording their debut, Rush, on their own Moon Records label, the bassist and the guitarist fell out with Rutsey, a competent but rudimentary player (who today, according to Lifeson, is a professional body builder). In August 1974, Peart auditioned, and both Lifeson and Lee remember it well:

"He was playing this small kit of Rogers drums," recalls Lifeson, "and he hit them so hard, it was unbelievable. It just lifted the music right up."

"Plus," chimes in Lee, "the more we talked to him, we realized he was into the same kind of music and had the same sense of hurnor-all these common denominators. It was just like finding the third piece of the puzzle."

Since that time, six of Rush's albums have gone platinum; three, gold. And at this point, there exists among them a rapport that Lee attempts to put into words but can't. Producer Collins calls it a brotherhood.

"It was very impressive," he says, "and very unusual. They have this kind of rap among themselves. If one of them is down, this rap sort of happens, and it picks the person right up."

"I've never seen our kind of relationship in another band before," contemplates Lee. "I was watching Sting being interviewed on TV the other day, and he was saying how he couldn't understand why anyone would want to stay in a 'gang' all his life. And I immediately started thinking about my gang, the three of us, and I couldn't look at it that way. We're such strong individuals, yet we're much stronger as musicians collectively than we would be separately.

"And," he adds, "it's fun."

Hardly sounds like a band getting ready to pack it in. Concerning Rush's future, Lee says that Power Windows was "a very pleasurable album to do"-unlike its two predecessors-and may have suspended temporarily the eventuality of a breakup.

"As far as a recording entity, yes, it's pushed the end of the tunnel farther away," says Lee. "Doing this album, becoming a little more daring in that area, has helped extend our lifespan.

"The problem for us right now is getting a balance between the band and other things in our lives," continues Lee, who's spent half his life in the same band. "You have to consciously make time for those other things instead of just saying, 'Well, one day,' because 'one day' never comes-the band never goes away. So at some point we're going to have to force the issue and start pushing for time to do those things; figure out a way to still be around and still have fun."

Touring will certainly be cut back. "We've done it for so long," says Lifeson, "you feel you're missing out on other things. Plus, you don't want to end up just some burnt-out touring musician...

"But," he confides, taking the last puff on a cigarette, "it's all so strange. When we were winding down this record, I thought, 'God, I could use about ten years off.' Well, I've been home for a little over a month now, and I'm really itching to get back on the road.

"It's just one of those pressures that you have to face and overcome."

Knowing Rush, perhaps the most autonomous, stable unit in rock & roll, they will.

With grace.

Geddy's Gear

Welcome, Wal

Au Revoir, Rickenbacker

Stick Around, Steinberger

Geddy Lee recording without his trusty Steinberger? Or his Rickenbacker 4001? That's like Ian Hunter without his shades, or Prince minus purple.

Rush's bassist fully expected to cut Power Windows with the Steinberger he'd played exclusively since the end of the 1984-85 world tour, at which point the 4001 was put into storage after a decade. Lee did, however, bring along to England some pre-CBS Fender jazz and Precision models as backups, and when it came time to record his parts, plugged in all of his instruments, "just to note what they all sounded like, for reference."

Producer Peter Collins handed him a Wal bass, of which Lee was only fleetingly familiar but was eager to try. "It sounded very good," he says, "and I found I could play very quickly and easily on it. It had definition, which is great for me because I've always been a busy player; I've always played too much.

"Which I like," Lee qualifies, laughing. "But sometimes my sound would get lost. With the Wal, and with these light-gauge Rotosound Superwound Funkmaster strings, the detail up high was excellent and really sat well with the drums, so I used it for the first time.

"Before every track, we went through the same process, and by the time we were about halfway done with the album, I just said, 'Fuck it. I'm going to use this.'"

Lee's model is a long-scale with two pickups, and he has a five-string on order from the small British company. He expects to take both the Wal and the Steinberger on tour, with pretty much the same amplification as last year: Nady VHF 700 wireless system, two BGW 750C power amps, Furman PQ-3 parametric equalizers, two Ampeg 2-I5" cabinets and two Thiel 2-15"s. In the studio, as good as the Wal sounded direct, Lee elected to record it both DL and through a Yamaha G100-212 guitar amp, adding further punch to the sound, which he effected with only a Roland CE-2 chorus "so that I could overdrive the amp a little bit and get some dirt in there."

Fans of complex, dominant bass lines will delight over such tracks as "The Big Money" and "Grand Designs," on which Lee executes nimble runs and negotiates turn-on-a-dime accents. One such fan is Neil Peart, who says that when it's time to record his rhythm-section partner, "l'm usually hanging over the engineers shoulder, going, 'Come on, come on, turn up the bass!"

"Yeah, Neil's the one I ask whether or not the bass is too loud," says Lee. "Even when it's screaming loud and smashing your face, nine times out of ten I still end up getting to turn it up.

"Which," he laughs, "may be why I value Neil's opinion so much."

Sound Check

Gear Used on 'Power Windows'

750D power amp, manufactured by BGW Systems, 13130 S. Yukon Ave., Hawthorne, CA 90250, (213) 973-8090.

BGW no longer manufactures the 750C, the nonmetered power amp employed by Geddy Lee both live and in the studio, but it can still be found in many stores for $1,399. The current model is the 750D, the features of which include: toroidal power transformer; Ultra Case power transistors-stronger than MOSFETS and twice as strong as the 750B's transistors; more than 1kw of clean audio power; for driving the most difficult load with ease; and improved thd of approximately 70 percent.

Suggested retail price: $1,499.

Rock-747 drumsticks, manufactured by ProMark, 10706 Craighead, Houston, TX 77025, (713) 666-2525.

The original 747s are made of Japanese white oak wood, but they are also available in American hickory which is about 10 percent lighter in weight. The 16.25"-long, 9/16"-diameter sticks come with either nylon or wood tips. Neil Peart favors the latter, and has his drum roadie, Larry Allen, sand the varnish off the butt ends. The tip shape is almost the same as a 5B's, while the neck, or taper, portion of the sticks is thicker and stronger than a 5A's.

Suggested retail price: $6.89 (wood tip); $6.99 (nylon).

Wal bass guitar, manufactured by Electric Wood Ltd., Sandown Works, Chairborough Rd., High Wycombe, Bucks HP12 3HH, England, (O11-44) 494-442925.

Not currently distributed here in the States, Wal basses are individually made by experienced craftsmen, turned out at the rate of just five per week. Features include six-piece laminated neck (rockmaple, hornbeam or Amazonian hardwood); 34" scale length; 21 nickel-steel frets; unique hand-rubbed and polished finish; Schaller low-gear heavy-duty machines.

Suggested retail price: $1,000 (for standard Wal bass, without case), plus $80 for freight charges as well as l4.5 percent import duties.

Classic Tracks

"Fly by Night" (from Fly by Night, 1975)-Lifeson: Gibson ES-335 guitar, 100-watt Marshall amp, 4-l2" Marshall cabinet, Maestro phase shifter; Lee: Fender Precision bass, recorded direct; Peart: seven-piece chrome-finish Slingerland kit with Zildjian cymbals.

Lee: "I eventually mutilated that P-bass; in a moment of insanity I cut it into a teardrop shape and painted it like a '57 Chevy. I apologize to it whenever I see it..."

"Closer to the Heart" (from A Farewell to Kings, I977)-Lifeson: Gibson Dove acoustic guitar, Gibson ES-355 guitar, Roland JC-12G amp, H.H. head, Hiwatt cabinet; Lee: P-bass, recorded direct; Peart: 11-piece black-chrome-finish Slingerland kit with Zildjian cymbals, glockenspiel, assorted percussion.

Peart: "The album opens with a little classical guitar/glockenspiel/minimoog intro that we recorded outdoors, live, at Rockfield Studios in Wales. Those are real birds tweet-ing in the background."

"Tom Sawyer" (from Moving Pictures, 1981)-Lifeson: Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion guitar, four Marshall 2-12" combo amps, Loft analog delay; Lee: Fender jazz bass, recorded direct and through Ashly and BGW 750C power amps, and two custom-made 2-15" cabinets; Peart: 14-piece rosewood-finish Tama kit with Zildjian cymbals.

Peart: "In terms of physical output, that and 'La Villa Strangiato' were the two most difficult songs we've ever recorded. My hands and feet were so sore from laying down the basic track. It was difficult mentally too, because of the rhythmic shifts it goes through."

"Subdivisions" (from Signals, 1982)-Lifeson: black customized Stratocaster guitar; Loft analog delay, four Marshall 2-12" combo amps, Yamaha E1010 analog delay; Lee: Rickenbacker 4001 bass, recorded direct and through Ashly and BGW 750C power amps, and two custom-made 2-15" cabinets; Peart: 14-piece red-finish Tama Artstar prototype kit with Zildjian cymbals.

Peart: "Geddy and I came up with that song one day while we were mixing our last live album, Exit...Stage Left. l'd already written the lyrics." (Peart, by the way, delivers the basso-profundo "subdivisions"on the chorus, not Lifeson, who's shown mouthing it in the song's video.)

"Distant Early Warning" (from Grace Under Pressure, 1984)-Lifeson: black Strat on verse, white Strat on chorus, four Marshall 2-12" combo amps; Loft analog delay, two Yamaha E1010 analog delays, DeltaLab harmonizer; Lee: Steinberger bass, recorded direct and through Ashly and BGW 750C power amps, and custom-made 2-15" cabinets; Peart: 14-piece red-finish Tama Artstar prototype kit with Zildjian cymbals.

Peart: "In the middle of working on that album we took off some time to play several shows at Radio City Music Hall in New York. Then we came back to the rehearsal hall, and there was such a fresh input from having played live. 'Distant Early Warning' was one of the songs that we wrote right away after we returned."