The State Of The Art - Neil Peart

By Scott K. Fish, Modern Drummer, January 1986, transcribed by Terrance A. Stedman

HALL OF FAME: 1983

ROCK: 1980, '81, '82, '83, '84, '85

RECORDED PERFORMANCE: 1981, '82, '83, '85

MULTI-PERCUSSIONIST: 1983, '84, '85

PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTALIST: 1982

MOST PROMISING NEW DRUMMER: 1980

Like attracts like. As I've traveled about the northeastern portion of the U.S. over the last two years, I've run into Neil Peart fans in the strangest places. When I meet people for the first time, they'll usually ask, "What do you do?" "I'm a writer." "What do you write about?" I answer, "Many things, but mostly I write about drummers." These people generally excuse themselves in short order.

Neil Peart fans are different. One evening I was at a lecture, and I began a conversation with a busboy who told me that he was an aspiring writer. "What do you write about?" I asked. "Mostly poetry." "Which poets are your favorites?" "Well," he said, "I really like Neil Peart. He writes lyrics for a group called Rush."

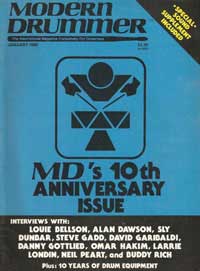

I could tell you about a handful of such encounters. One thing is for sure: Neil Peart has influenced, and continues to influence, a lot of young people. Surely he's no stranger to MD readers. He's been on MD's cover twice, he's won numerous times in numerous MD Reader's Poll categories, he's written articles for MD, he is continuously being asked questions in the Ask A Pro column, and he even gave his drumset away through the magazine!

This interview was done over the telephone. Neil had been home in Canada for a few days after spending several months in England recording the new Rush album.

Have there been any people, styles, or technological advancements in the last ten years that caused you to grow, or that changed your style of drumming?

Certainly there have been, although it tends to be less one person than it is the old "passing of the torch," where one drummer develops things to a certain extent, passes it on to someone, and so on. The progress of almost anything is very much like a relay race, but particularly in drumming, because it's such an interior field, restricted to the people who do it and to the people who really care about it. It kind of goes on behind closed doors, but that advancement is always moving forward.

In retrospect, the largest advancement over the last ten years is electronics. Love it or not, it is a major thing. The people who lead the field in that, to my mind, would be Bill Bruford and Terry Bozzio, in different ways. The explorations that these guys make work to everyone's advantage. I don't want to go as uncompromisingly electric as Terry Bozzio has gone, but at the same time, I can enjoy and appreciate what he is doing, and admire the courage and technique that it takes to really do it well. You can listen to electronic noise and know that it doesn't mean anything, but when you watch Terry Bozzio play electronic drums, it is exciting and essentially musical, because he has the technique to back it up. The same goes for Bill Bruford, with his more rhythmic, ethnic kinds of explorations.

Even a non-drummer like Thomas Dolby, for instance, uses a lot of electronic drums and drum machines, but as a musician, he has a great sense of rhythm. As a drummer, I find it satisfying to listen to. Peter Gabriel is another example of that. He's not a drummer, but he has a great sense of rhythm - what rhythm is and what it can do. Consequently, his music is very influential to me, even though he uses a number of different drummers and sometimes just drum machines. He has the ability to make it all have rhythmic integrity, which is difficult when you're drawing from ethnic sources the way he is.

Recently, I had a telephone conversation with a good friend. He's a well-known drummer who's very much involved and interested in drum electronics. He had played on the last 11 albums of a major artist. On the twelfth album, a drum machine was used instead. My friend's snare drum sound was processed onto a digital chip and used on the album. So he wasn't on the album, didn't get paid, and yet in a real sense he was on the album soundwise.

There's a real new morality that has to be developed for sampling. In looking ahead to the next ten years, the biggest thing that will be happening is the ability and facility to make your own digital chips - sampling any sound under the sun and having it as part of your drumkit. This is something that I'm moving into right now, and I'm sure I'm not the only one. It's so intriguing to have otherwise unattainable sounds. It's not going to come even close to replacing my acoustic drums. My drumset isn't going to get any smaller or look any different. But the electronic things that I use will be used in so many different ways.

The morality comes into it in just such an instance as you mentioned. I ran into that during the recording of our new album. We were looking for a particular sound, and somebody suggested that we take it off so-and-so's record. I said, "No, no, no!" It's that person's sound. The work involved in creating a sound is sometimes comparable to the work involved in coming up with an idea for a song. Stealing someone's sound is akin to stealing someone's song, as far as I'm concerned. You can't help being influenced by a sound. You may even try to imitate it, just as you may try to imitate a song. It's still not the same as out and out copying. For instance, we set out to get African sounds out of my drums. That's not the same as taking a sample off of someone else's record and making a chip out of it. It works both ways. I wouldn't be happy if it were done to me. I know what it sometimes takes to get a good snare drum sound, and the amount of work, experience, knowledge, and tuning ability that it takes - not to mention the engineer's ability to place the microphones and put it on tape properly. There are an awful lot of people's lives literally involved in that process. For someone to just swipe that off a record rubs me a little wrong.

My friend's reaction to it was a loss of enthusiasm towards drum electronics.

Yeah. Again, it can work both ways. For example, there is one song off the new album where we were playing all my Simmons drums with samples. I rented a whole pile of African drums - some big giant ones covered with some strange kind of skin - some Indian tabla drums, and all different things. We went through them all and chose the ones I wanted to make a drumkit out of. Two tablas, a talking drum, and a giant African tribal drum became my four tom-toms. I was able to play the instruments myself, make the samples from them, have chips made, and that became my drumset.

Our producer works in London all the time. He's become very jaded about the Simmons sound. He didn't really want to hear it, so we found other ways of getting around that. There were times when I vocalized a little single-stroke roll, and that's exactly what you hear - my voice doing a single-stroke roll. That was exciting - a very natural way of using electronic drums. The African drums are really the most primitive kind of drums there are, and I was using the cutting edge of electronic technology to reproduce them. When you take that further to where you can have the sound of cars being crushed, glass breaking, or garbage cans falling over - any one of these sounds can have the potential of being part of a percussion ensemble. That's where it becomes exciting - where it becomes honestly innovative and exploratory. Copying off other people's records is incestuous.

Drum machines have the same potential. I think they are starting to become less prevalent on records. More and more people may be putting things down with drum machines, but they have real drummers come in and make it feel good. Drum machines are for songwriters. As a songwriting tool, they're invaluable. You can't begrudge them. They help the drummer out by giving an accurate picture of what the songwriter really wants to hear. During the new album, these things came more clearly into focus.

Rush is a three-piece band where, basically, the other two guys write the music and I write the lyrics. A lot of times, when I'm off working on the words, they're working on the music. I'm not there to be a rhythmic part of it, but they can program a drum machine to give me some idea of how they're thinking. It becomes a springboard. I could never play a song the way a drum machine would, particularly because I'm a hyperactive player. But I certainly use it as a foundation, and often a very interesting one. Sometimes it points me in a way that I wouldn't have otherwise explored. Sometimes they come up with something on the drum machine that sounds deceptively simple, but it can be a springboard into interesting areas.

You're admired as both drummer and lyricist. Phil Collins is admired as singer/songwriter/drummer. Stewart Copeland has been writing movie soundtracks in addition to his drumming. Do you think that this role expansion by drummers is a healthy sign that we'll see more of in the future.

I would have to think so. It's difficult to know. I think that the ability to organize words is the same mental process as the mathematical ability to organize beats and subdivide time the way drummers do. For me, the transition to words is a natural one. From the first time I went to school, I was always in love with language. I tend to think that drumming does have a lot in common with words, but the two may not always go together.

If people are at least thinking of other things - certainly more drummers would think about singing through Phil Collins' work, or about getting more into composition and textural works as Steward Copeland has done, or about writing lyrics. All of these can contribute so much to a band. It seems to me that doing arrangements is the natural area for drummers to move into first. That's where I think I started to get a little more adventurous in music before I ever thought of writing lyrics. I liked to contribute arrangement ideas to the band - intros and outros - because they're fundamental things that a little imagination can help you communicate, and you don't have to develop your theoretical knowledge. There's probably a trend now - maybe you know more about this than me - for drummers to be better educated harmonically. They might start on or learn another instrument contemporaneously with drums, or they learn harmony in school.

In my optimistic moments, I agree with you. However, I see much evidence to the contrary, where many young drummers are asking, "What's the least amount of work I have to do, in order to get the most from my drumming?" Max Weinberg has a theory that we might be seeing people who strive to master the drum machine instead of the drumkit.

Drums are such a physical instrument though. That would already require a different mentality. One of the things that I liked about drums from day one was that you hit them. I don't think that will change in a lot of cases. A kid who gravitates toward the Linn, for instance, would probably otherwise have been a keyboard player or a computer programmer. That person's affinity for drums wouldn't have been the same as mine. Mine was very much a physical affinity. First of all, I very much related to the way that drums looked. The first time I ever saw a set of drums, I thought they were beautiful things. Second, of course, is that you play them by hitting them. It was a physical relationship that I responded to right away. I was a lot more interested in that than tinkling a piano, plucking strings, or blowing into things.

A person who comes into it with that same kind of approach would maybe go towards electronic drums. Electronic drums have a lot of learning advantages, really. As the pad surfaces become more perfected, which they seem to be, there will be no disadvantage in that. It will give you the advantage of being able to practice a lot, which I wasn't able to do, because of the loudness of drums. That's a limitation in a physical sense, too. Hopefully, drummers will study both acoustic and electronic drums, and hopefully things like touch, dynamics, and the subtleties of playing - that only real drums can ever give you - won't be lost. It may be that a person who can afford an inexpensive acoustic drumset will, instead of saving for another acoustic bass drum and tom-toms, be saving for a supplementary electronic set. They will get less and less expensive. All those types of machines do. It will be possible for a person to have a small acoustic set and a small electronic set, instead of expanding an acoustic set too quickly, or buying a lot of things for which the person has no use.

There's an aspect of the professional use of electronics that must be frustrating to young drummers. Your use of African drums on digital chips is an example. It seems that, unless young players have an awful lot of money, there's no way that they are going to be able to duplicate many of the sounds they're hearing pro drummers use on today's recordings.

It is true that the drumming of Terry Bozzio and Bill Bruford - especially the stuff Bill did with King Crimson - is really difficult to reproduce without some sophisticated equipment. It's still nothing like the nightmare the keyboard player faces. With drums, you can buy a Clap Trap for a couple of hundred bucks and get some interesting electronic sounds to play with. What you have to have nowadays to be even remotely on top of the leading edge in keyboard technology is frightening. Keyboards are getting smaller in size, higher in price, and greater in capabilities, which means that you have to learn so much more. How many years does it take to learn to play a piano properly? Then add the amount of knowledge that you have to further acquire to understand and explore fully the abilities of electronic instruments.

It's getting like that for drummers, too. I'm a little daunted by what I'm having to get into to do what I want to do right now. I don't have the kind of mind for which electronic things are immediately crystal clear. I have to spend a lot of time, sweating over the manuals. I've taken steps to acquire the latest Simmons E-Prom system, so I can make my own chips. I'm really excited by the potential of that. I wouldn't let myself not do it, but at the same time, I know I'm letting myself in for a lot of aggravation and headaches. Beyond the 20 years that I've spent trying to make myself a reasonably proficient drummer, all of a sudden I feel like I'm starting in kindergarten again.

Do you have a reaction to the flood of cosmetic drum products we're seeing now? In a recent MD article, one drum manufacturer was attributing the cosmetics to the rise in popularity of video.

I've always been into the visuals of drums. I've always liked a good-looking drumset. Video hasn't changed that for me. Since it's my work place, I like to have my drumset neat and looking nice. It could be that these cosmetic products are due to what I described, or it could be due to video. In many cases, you don't even see a drumset in videos. They either have a little token snare drum, bass drum, Simmons kit, or no drummer. Sometimes a drummer is hitting a piece of wood!

Are today's drums better made than the drums you played ten years ago?

There's no question that they are better. The standards of quality have certainly improved. I don't know if they sound better, and that has to be the bottom line.

Putting endorsements aside for the moment, is there any drumset you've owned that you felt was better than any other drumset you've owned?

I couldn't say that, but the first good drumset I had certainly meant more to me than any other could. That's only natural. I started out with a really cheap set of Stewart drums. When I went up to a set of Rogers, it was the greatest thing. How can I describe that? I don't know how they would compare soundwise to today's drums. The sound hasn't gotten worse, that's for sure.

Moving on to styles and influences, you don't seem to be influenced much by jazz.

Well, of course, my roots do come from jazz. I grew up listening to big band jazz, which my father loved - Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and the great drummers who played with them. Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett always had great musicians, and drummers like Gene Krupa and Kenny Clare influenced me greatly - such disciplined exuberance. These days, I must admit that I like the side of jazz that deals more with the thrust and organization of rock. When jazz lacks that, it tends to lack me. Heavy Weather by Weather Report was a very influential album for me. All the stuff that Bill Bruford did on his three or four solo albums was also really, really great.

I have to tell you that I recently got to play on Jeff Berlin's solo album. On one track, I got to play together with Steve Smith. Steve actually did most of the playing. I just came in on the choruses for that "thunderous double-drum effect." That was a lot of fun and a real exciting challenge. It was a major milestone for me to walk into a situation like that with no rehearsal. All I'd ever heard of the music before was a living-room demo with a beat box.

Isn't that the first time you've recorded with someone other than Rush?

No. I did a similar thing with a musician named Ken Ramm in Toronto. That record was released in Canada.

Who are some drummers who've influenced you, other than the ones you usually mention?

There certainly have been many, but they're always so hard to pull off the top of my head. Simon Phillips, Andy Newmark, and Stewart Copeland come to mind, as well as Jerry Marotta. I particularly like the work that Jerry and Phil Collins have done with Peter Gabriel. I like ethnic ideas. I listen to a lot of reggae, and the percussion on modern African music - like King Sunny Ade - has been very influential to me. I like Rod Morgenstein a lot; he's a good player and a lovely guy. Warren Cann from Ultravox, Steve Jansen from Japan, and Chris Sharrock from The Icicle Works do some interesting things. I'd also like to add Omar Hakim, Peter Erskine, and Alex Acuna to the list.

Regarding your own playing, some people I've spoken to feel that Rush's last two albums were more commercial than usual. Was that on purpose? Is the new album going to be more progressive?

Well, if we were trying to be commercial, we failed. It's the continuing stages of growth as far as we're concerned. The more we learned about technique, arrangements, compositions, and all that, the more we got involved with it, and the less important instrumental panache became. Once you've done it, it ceases to be important. Once you've done a few long instrumentals in 7/8, 9/8, 21/16 and what have you, there's never any point in redoing it. The fact is that we've done it, and it will always be a part of our music. There's a nice long workout in 7/8 on the new album, because we've found a new way to use an idea like that. On the last album there were dabblings in odd time, but it's become less important. That's all. We know ourselves that we can do it, and we've explored its possibilities.

We had to go on to something else, which for us was song structure. We took our technical ability along with us, and now when we go to arrange a song, nothing stands in the way of trying any kind of different permutations or rhythmic shifts. More and more you look for different ways of achieving texture, and different ways of using melody and computing song arrangements - where you place the verses and choruses, what kind of intro you develop, and how you work the instrumental sections into the pieces of the song. All of that has gotten really fascinating for us.

We think that the face of our music is changing from having been progressive to not being progressive. For us, we're progressing. That's all that progressive music can be, and it's just as difficult for us to think of and to play. To us, it's totally satisfying and progressive. Perhaps from the view of an outsider who judges only on the superficiality of technique, it might seem simpler. Believe me, it's not.

Looking ahead ten years, would you like to take a stab at what you might be doing, and what other trends and styles of drumming might emerge?

It's tough to play soothsayer. Electronics moving into the area of sampling, being able to make your own chips - this is a very important turning point. With the miniaturization and availability of these things to the average learning musician, the trend towards having both acoustic and electronic drums will grow. That's very healthy, but it always has to be good for a drummer to start on real drums. They have subtleties and tonalities that I don't think electronics will ever manage to imitate totally. They have become a separate thing unto their own. They've become a percussion instrument, really, more than a drumset. The potentiality, especially for percussion, of having your own drum chips of any sound at the hit of a stick or the tap of a foot pedal is an enormous growth. It has to be good. But the things I mentioned earlier are all percussion ideas. I don't think they're going to add to a fundamental drumset. They can't replace what an 8x12 tom-tom sounds like, any more than they can replace what a 24" bass drum sounds like. Electronics has really failed in its emulating sense, but at the same time, it has opened up so many doors toward different things that are really exciting.

Improvement in pads will be a very big road in the future. They definitely have to get better. Just about every year, a new design in pads comes out with better and more lifelike response. But it's still an enormous gulf between getting lifelike pads in response and lifelike pads in terms of sound reproduction. How many different sounds can a snare drum make? What an acoustic snare drum can produce is enormous. But is it possible to program each of those variables and each of those sound possibilities electronically? I think we're a long way off from that, if in fact that ever becomes possible.

So, you don't see the death of the art of acoustic drumming?

I'll be brave and say no. All the predecessors dictate the rightness of that. The grand piano isn't gone yet. The acoustic violin isn't gone. The acoustic guitar is still here, and look at the competition it's had! I'll take a chance and say that acoustic drums won't be gone either.