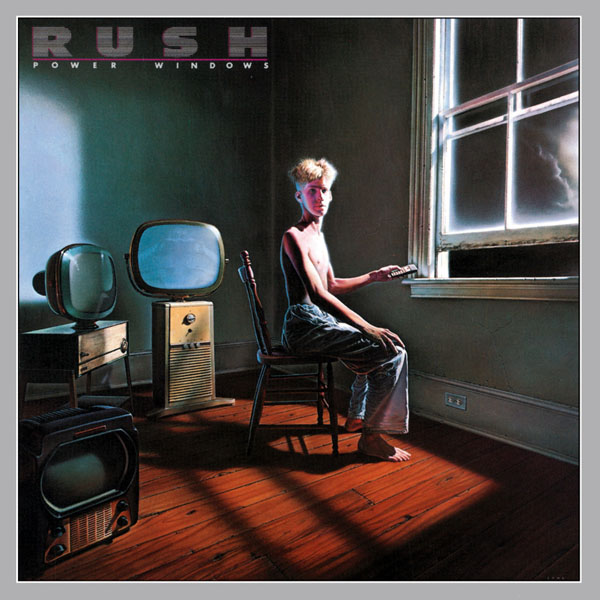

Rush Tunes Out Growing Temptation To Go Quartet

By Daniel Brogan, Chicago Tribune, March 20, 1986, transcribed by pwrwindows

To be three or not to be three, that is the question for Rush.

For 10 years and 12 albums, Geddy Lee, Neil Peart and Alex Lifeson watched their music grow beyond the limits of bass, drums and guitars. Lee began dabbling with keyboards, but until their current album, they had always resisted the temptation to make the trio a quartet.

With "Power Windows," Rush finally brought in a pinch hitter: synthesizer wizard Andy Richards. Richards added a creative spark to the "Power Windows" sessions and showed the Canadians tricks far beyond the capabilities of Lee's modest keyboard skills.

The end result is an album that at last succeeds in melding the disparate influences (everything from reggae to U2 to Led Zeppelin) that had muddled the band's most recent studio efforts.

But as much as the band enjoyed working Richards ("Andy was great, he really expanded our horizons," says drummer and lyricist Peart), Rush will still be a trio when they come to the Rosemont Horizon Friday and Saturday.

"Adding a fourth man is a specter we've had to face for 10 years," Peart says. "As soon as we began running up against the limitations of three instruments, we began talking about it."

But the bottom line, Peart concludes, is that "we like being a trio."

"There's a very good chemistry here," he says. "And we don't want to do anything that might upset what has been a very good balance professionally and personally."

That, however, doesn't mean that only three-quarters of the "Power Windows" sound is reproduced in concert. "Thanks to computers and digital samplers, we're able to store Andy's sounds and effects on floppy disks that can then be triggered and played through Geddy's keyboards," Peart says.

(Don't confuse digital sampling and simply playing along with a pre-recorded tape. Sampling involves recording an individual sound or effect and then assigning it an instrument, such as a keyboard or drum machine, which then is played in the traditional manner. For example, you could "sample" the sound of a car door slamming and then play a drum solo in which each beat was the sound of a door slamming.)

In fact, Richards' parts are the least of Rush's on-stage problems.

"Power Windows" marks the first time the band has recorded an album that wasn't tailored for live performance.

"In the past, whenever we tried something in the studio we stopped ourselves and said 'how will we do this live?' This album is the first time we've stepped outside that discipline," Peart says. "Our new producer, Peter Collins (Nik Kershaw, Musical Youth, Gary Moore), helped convince us that it was more important to give the songs whatever they wanted or needed, and worry about reproducing it later."

Reproducing the album's jumble of sounds proved to be a gargantuan task. Once again, the time seemed ripe for a fourth set of hands. And once again, computers saved the day.

"It took lots of preparation," says Peart. "In fact, we needed more time getting ready for this tour than any other. Geddy had to spend all sorts of time getting everything on disk and getting everything catalogued. But you'll see that we can pull it off. There are plenty of good reasons for going to four people - God knows we've considered them all - but making our own lives easier isn't one of them."

If it seems that technology is getting too good a rap here, let it be known that there are drawbacks. For one, off-stage technicians suddenly take on the importance of air tanks to a scuba diver. While the musicians are playing one song, the technicians are loading disks for the next.

"Your technician is no longer someone who just fixes something if it breaks, he's intimately involved in your performance," Peart says. "You've got to trust him a lot more than ever before."

But technology's biggest drawback is the spontaneity it robs from a show. With all those buttons to push, there isn't time for much else.

"When we're so busy doing things like programming and loading, it takes away from our freedom and it takes away from the mayhem that's supposed to be a part of rock and roll," Peart says. "There's no doubt about it, spontaneity can definitely be a casualty of the technological revolution.

"But the challenge is what makes it worth it," he adds. "It makes it fun in a different sort of way. We get to the end of the show and there's a certain satisfaction in knowing that just the three of us pulled it off. I think the fans appreciate that too. After all, that's always been our biggest challenge: to see what the three of us can do, not what four or five of us can do."