Fire In The Hold

By Deborah Parisi, Music Technology, February 1988, transcribed by pwrwindows

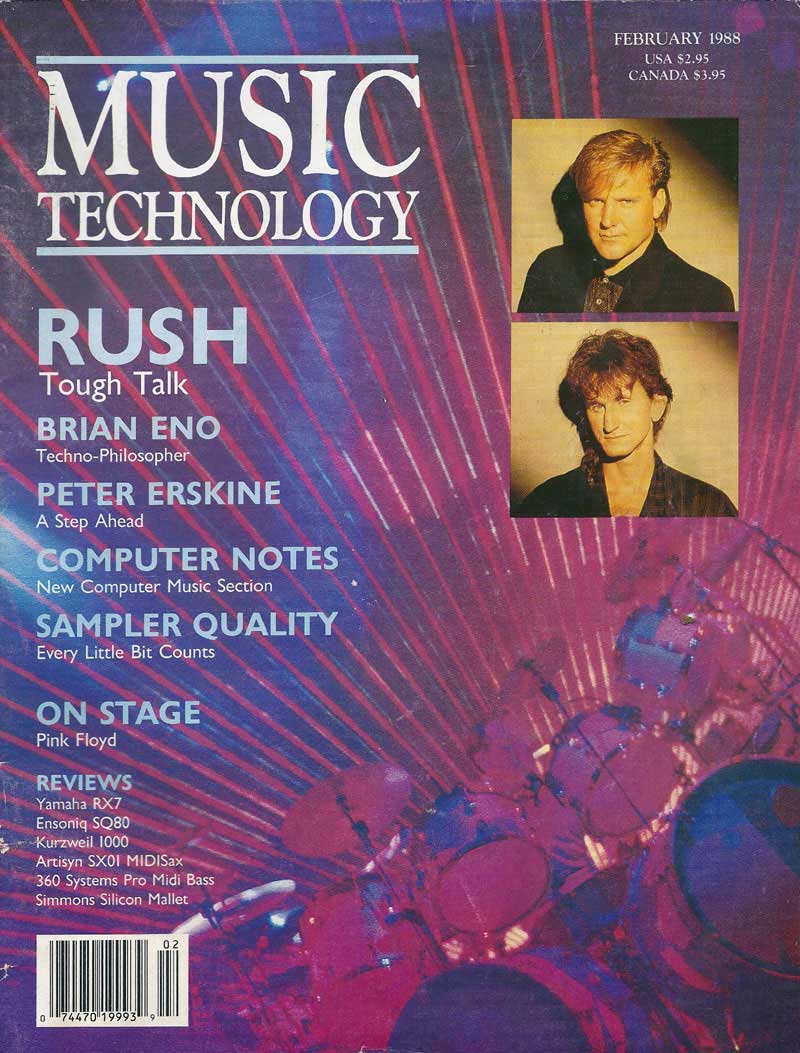

IN THIS ISSUE...Rush On the road again promoting their 12th album, this flashy progressive rock band forges on. Drummer Neil Peart and guitarist Alex Lifeson tell how they were saved by technology in the studio and on the tour.

With thirteen years and twelve studio albums, Rush is in the midst of yet another highly successful national tour. Drummer/lyricist Neil Peart and guitarist/inventor Alex Lifeson reveal the technology behind their setups and their shows.

HOLD YOUR FIRE. It takes a really good poet to give new meaning to an old saying. Although poetry - or, to avoid the austere gazes of the literary critics, popular poetry - relies on images that we can all relate to and understand, using a cliché to convey a central message is usually disastrous. It smacks of sell-out, burn-out and blow-out. Not a good idea.

But few critics are accusing Rush of any of the -outs these days. Their musical growth has progressed from screeching heavy metal through classification as "poor man's Yes" to a brand of technologically-assisted rock which is truly their own. Live performances have become increasingly polished and (not unexpected) glittery, with the production quality of their albums following suit. And the lyrics of Neil Peart have gained new insight, moving away from fantasy, futurism and science fiction to explore the primitive, the primal.

"I guess it happened by accidental design," Peart says of the poetic theme of Hold Your Fire (Polygram). "I realized that without really consciously thinking about it, I was into the world of instinct and the world of temperament, and subconscious kinds of things - Jungian things, certainly. And the only thing I could do was to go with it. It seemed to be where my muses wanted to take me. So the rest of the album indeed did follow that, and I broke it down into various subthemes beneath that common umbrella of instinct and temperament."

Although new songs like 'Force Ten' and 'Second Nature' display a social consciousness reminiscent of the Vietnam era, Peart doesn't see a general trend of '80s lyricists in that direction. "Every once in a while I get hopeful, and I think I see that trend. And then it goes, and a whole hunch of pap comes out, and people are just as happy with that. It became its own fashion, you know, throughout the whole Live Aid thing. The whole industry was like standing up on this pillar and saying, 'Look at me, look at me! I'm generous!' And it died... possibly because of the posturing that went with it and its essential hypocrisy. Like the punk movement, it had to collapse from within because you had a lot of people saying things that their day-to-day lives and the rest of their work just didn't back up. So I think that big wave - in spite of Roger Waters' hopefulness - I don't think the tide is turning. I just think it was like a tidal wave that came in and went out again.

"It is an old, old story, that goes back to politics, to baby kissing. It's just trying to make yourself look really good to the people down there and have them think, 'Gee, here's a regular guy. He's up there, but he's got a big heart.'"

Peart is just as candid in discussing his stance towards technology. "I'm not a pioneer by any means. I sort of take the Rolls Royce attitude of letting other people pioneer things and prove them and then adopt them - like Rolls Royce uses General Motors power steering because they make the best power steering. You don't have to pioneer if somebody else does it. You can still be just behind the leading edge but have the advantage of things that are reliable. And you avoid the trendy aspect of things like Syndrums, where in the early days every beer commercial had that sound on it, and you avoid having to wince about your past.

"When I finally figured that digital sampling had come of age and it was a tool that I really wanted to have and could no longer resist, I went to Jim Burgess at Saved by Technology [a Canadian company specializing in MIDI equipment and system applications] and said, 'Here's what I want to do, and here's what I don't want to do.' And he recommended a setup and worked with me a lot to get the gear and the library of samples from my older records. It's good to have someone like that to steer you in the right way."

Burgess "steered" Peart into a system which incorporates samplers, MIDI controllers, and pads. "All the pads are assigned through a Yamaha MIDI controller, the PMC1, into an Akai sampler, and that's triggered by Simmons pads and also by a footpedal. My left foot bounces around from hi-hat to bass drum pedal to triggering pedal - it does a lot of work down there," he laughs. "I also have a small home-made trigger which we affectionately call 'Sydney,' which is virtually a miniature Simmons pad. It's octagonal, but it's only about 3" across, and it allows me to trigger sounds from my front kit without having to take up the space that any of the proprietary pads require. It's something that we came up with ourselves - shock-mounted and very sophisticated now, but strictly a unique item."

According to Burgess, designing the system that the band has on the road was quite a challenge. "One of the problems we had was that the band didn't want to he restricted by playing to a click-track, so a hardware sequencer wouldn't really work," he says. The alternative was to sample sequences that had been used in the studio so that band members could trigger two to four bars of repeating phrases with the tap of a foot or key.

Geddy Lee, the co-writer, bassist, an keyboard player, uses an astonishing number of keyboards and modules for his performance. On stage, he has a PPG, Prophet VS, D50 and a Yamaha KX76 that are being used as controllers. In addition, he uses Korg MIDI bass pedals and Taurus pedals to send program change information. In "the pit," he has seven S900s, two Roland D55Os, one D50 and a DX7 with an E! mod, along with four of Intelligent Music's MIDI Mappers. Manning the pit is Jack Secret (an alias), whose job requires loading close to 100 disks into the various samplers at the appropriate moments. More than minor pressure, there; one wrong disk and a song could be ruined.

All of the controllers run into two JL Cooper MIDI patchbays, which are set up in a parallel configuration and modified with a custom-made A/B switcher from Hi Tech Music Systems so that patchbay #2 could take over if patchbay #1 went down.

"The other important part of my system is a KAT controller," says Peart, "and I use that for all keyboard percussion parts plus another triggering source, because it has its own Akai. So sometimes when all the other pads are full, I'll put the sound I need on the keyboard so I can just whack it and the sound comes out. In the past I used to have a glockenspiel over there, and a set of the little tuned cymbals that are called crotales (a Turkish bell cymbal), but those kind of things are enormously difficult to mic, and for the amount of space they take up they only offer you one sound.

"On one song called 'Mission'," he explains, "there's a marimba solo. On the record I used a syncopated snare drum matching in unison with the marimba part, and Geddy plays a bass part also in unison with that. So what I did for the tour was assign the sounds of both the marimba and the snare drum for that particular song, so that I can have both of them as I play the keyboard part. Within the same unit I have other straight marimba parts and glockenspiel parts and various other sounds, so it's been very valuable. I wasn't sure at first if I would use it live or how successful and reliable it would be. But since it has been good, now it has my faith.

"That's essentially it," he says, "from pads and triggers into a MIDI controller, and of course the KAT is a MIDI controller by itself. I use a couple of Alesis Midiverbs just to make these electronic sounds sound more like my acoustic drums do in the environment."

Peart is also an enthusiastic endorser of the new Zildjian cymbal mics. "I'm very happy with those. Again, as I described in respect of glockenspiel and crotales and wind chimes and that, all that stuff is so hard to capture in an arena. I was always haranguing our soundman with, 'Why can't I hear that little cymbal?' So now, combining those individual Zildjian mics plus the overheads, you get both. You get the overall picture of the air around the cymbals, but you also get a good individual capturing of that sound."

The Akai S900 has also become a trusted tool on the tour, bringing Peart's rhythms into the digital domain. "I have done quite a bit of sampling myself. In fact, on one of the songs - ironically I'm using Ludwig drums now - but I have samples of my previous Tama set. I took those samples and assigned them to the electronic drums for one of the older songs. So I'm playing an old song with an old drum sound. It's great.

"On one song on the album called 'Tai Shan,' I have an antique Chinese drum which is far too fragile and valuable to think about using live," he continues, "and I brought it into our rehearsal studio and sampled it. I have a number of antique, especially Oriental and African, musical instruments that the only way I can use them is to sample them. So it gives you all that freedom. That's what I like the most."

Using samplers in place of sequencers allows the band to have a greater degree of control over the triggering of sounds. "It's a blessing for a three-piece band and to me doesn't carry the same moral stigma as using tapes for backing vocals or rhythm tracks," Peart says. "You have to work it out yourself, and program it yourself, and trigger it yourself I find it less of a crutch and more of a challenge. When a loop comes in and out of a song, like on the song called 'Prime Mover,' right from the first beat I have to he so locked into the tempo that every time it comes along it fits. It lets us make our sound as big as possible and lets us reproduce the records as closely as possible, and is still a tremendous challenge in trying to make it work."

Peart is one of many who compares sampling other artists to stealing. "It's a very naughty moral question," he says, "and I'm engaged in a struggle with myself because in my drum solo I do use some samples that are like Count Basie Big Band shots. The controversy is strongest, of course, when you lift, say, a snare drum sound off a record and use it as a snare drum sound. A drummer learns over the course of many, many years how to tune that drum, and the engineer learns after many, many years how to record it to get that sound. The real pros...like Andy Richards who did keyboard work on our last two albums, he has classical things; but the way he uses them, they're all twisted and bent out of shape, and they bear no relation to their sources. So it does become a creative thing, and it's a long, long way from robbery.

"In a recording context," he continues, "I think it would give me more serious moral qualms. Live performance is frivolous enough that you don't need to take it that seriously. I allow myself the indulgence. Plus it's kind of a long-time ambition to play with Count Basie," he laughs, "so this lets me do it every night."

Peart has never used a drum machine for recording, but is thankful for its use as a songwriting tool. "Because of the fact that we work separately, where I'm working on lyrics and Geddy and Alex are working on music, it does all my hack work for me of keeping a beat while they work things out. And plus," he adds, laughing (albeit a trifle rudely), "Alex has a very extraordinary sense of rhythm which doesn't bear any relation to anything a drummer would do, so I have actually gotten some good ideas from strange patterns that he's programmed into the drum machine. It's sort of a humorous source of inspiration.

"It's the same as the way Geddy uses the Macintosh and the music software for that," he explains, "because he doesn't consider himself a keyboard player. It's just part of the load that he bears to contribute to the overall texture of our band. And consequently, he can work out all the parts he wants to play and then just say, 'Hey, Mac, play these!' It's just like having another member to do it, but you don't have to have the interpersonal chemistry changes of having a fourth member in the band."

ALEX LIFESON FIRST got together with Geddy Lee in 1969, five years before Peart joined them to create Rush. Although he is well known for his slashing, screaming, heavy metallic guitar, recent albums have revealed a rhythmic and melodic sensibility which transcends the abilities of most of his peers. Even a casual stroll down the musical trail left by the band over the past 12 years displays his and Lee's growth as the writers for Rush's tunes.

Writing the music for an album typically takes about four months of intense work. On Hold Your Fire, they started working together at Elora Sound near Toronto, which provided a quiet rural spot on a farm - the studio is actually located in a barn. "We set up the Teac 388, a small eight-track unit I have, in the studio. We had all our gear set up there, but we picked a little corner, put some nice lighting in, set up the 388, and plugged our direct bass and keyboards in," Lifeson explains. "A typical day would be up at around 10:30, breakfast together, discuss what was happening or whatever, and then Geddy and I would start working around noon in the studio. Neil would stay in the house working on lyrics. Then would come over about 5:00 and we'd spend an hour discussing arrangements, lyrics, and Neil would give us a critique on the musical end of what we'd come up with. Then we'd break for dinner, and after dinner we'd work together as a band on the songs. It developed to the point where after about a month, we could start recording into the 24-track and then start refining it. Working like this, we're totally prepared before we even go into the studio. We don't have to spend additional concentration while we're recording on rewriting something. It's very precise."

From Canada the band moved through four studios: two in England, one at Montserrat, and one in Paris. "We went to the Manor in Oxfordshire because we got good results there with the drums," Lifeson says. "It's a really good room, all stone and wood, and the ceiling is about 30' high in the drum room. There are movable panels on the ceiling that you can reposition to get it to sound like you want.

"After that," he continues, "we just went to places we wanted to go. We thought we'd take a chance, and it worked out great. The important thing is to keep yourself up and doing it in a different environment. The bottom line, if you're concerned about economics, is that it's not going to cost you any more to go into one studio for four months than it is to travel around to try other studios. And prices are usually a little bit less outside of North America - depending on the fluctuating exchange rates," he laughs. "England was a bargain because at the time the dollar was very strong, so the money spent on flying over there didn't work out to any more."

Recreating an album for live presentation is always a tremendous challenge, and Lifeson uses a wide array of gear to assist in guaranteeing a slick, professional show. "I just started using TC Electronics on this tour," he says, "and I have a couple of 2290s and 1210s. I really like them because you can really do a lot of things. You can adjust the panning any way you want, you can set the dynamic control, you can reverse it so that you only have repeats when you're playing. And signal-to-noise is very quiet. With all the additional software you can get for it, you can really utilize the sampler. It's really quite an amazing unit."

Lifeson continues through the list of gear being used on the tour. "I also have a Roland DEP5 and a Yamaha SPX90 as outboard gear, and I'm using a Yamaha MIDI programmer, the MFC1. That lets me scroll through my programs, and all of my equipment is MIDI. That's especially handy with the SPX90 because you can type in the name of the song or whatever information you want in the display, so for the 20 songs that I do, I just type them in and scroll them through. That's really important these days, because it's very, very busy on stage for us.

"It's always been a rule with us that we wouldn't do anything in the studio that we couldn't do live," he says, "and that was fine in the past. But with Power Windows [Rush's last album], we thought we'd expand...to make the record for the record's sake. That was fine in the studio, but then it comes time for you to tour and you go, 'What did I do?' Fortunately, technology is at a state right now where it's a lot simpler and much more convenient, I think. That's probably the biggest thing that the advanced technology has going for it... quality in production."

While Lifeson is obviously a champion of many of the benefits of technology, he is not nearly so warm on guitar synths. "I never really gave it much time, though," he admits. "I've tried a few out, but don't feel comfortable with it. I think you have to approach it as a different instrument - it's not a guitar, really, it's something else. I spent a few weeks with the Stepp, and I thought, 'Well, yeah, that's kind of neat,' but for the kind of money that it costs, I couldn't...I thought it was really crazy. But it requires a different style of playing and technique. I'd rather fool around with the guitar and effects.

"When you look at how they've developed keyboard synths," he says, "you get a better picture. Geddy's got this Yamaha - he started taking piano lessons this summer, so he lugs it around - but the touch on it is just like the piano. You know, like a grand piano would be. They've developed that, and it sounds fairly close to a real piano sound. They've developed it so that the touch is the same. But they haven't done that with guitar synths."

Lifeson is also a bit of an inventor ("An inventor by trade," Peart laughs. "You're talking to a musical scientist there."), but it happened almost by accident. "A few years ago I was using both electric and acoustic guitars on stage," he says, "but I wanted to make the change quick, and I couldn't find a decent guitar stand. So I designed one and had it built. A friend of mine owns a music store just outside of Washington DC, and he said, 'Hey, this is a pretty good thing. Why don't I just run it in my catalog and maybe we can sell a few of them.' He sort of laughed about it, and I said, 'Sure, why not?' I think we sold three or four hundred of them,' he laughs.

"We had to think of a name, so we decided to call it the Omega Concern,' he continues. 'The last word in guitar stands.' Then I designed the Omega Lyric Stand, which lets you pin the lyrics up and turn all the lights off in the studio, still giving a nice warm light. It's a rear projection light, and all you see is the lyrics on this opaque screen, and it's nice and moody. But it's kind of a joke," he admits. Lowering his voice to simulate a DJ's, he recites, "'Whenever you need something that no one else has, Omega will be there.' Or 'At Omega, we're concerned.' Our motto is, 'We have what you need. You have what we want.'" Hey, when you're hot, you're hot.

The liner notes on Hold Your Fire offer a fairly standard list of thanks, but with the unexpected offerings of gratitude to Patsy Cline and "all cowboys everywhere." What? A country influence on a prog rock band? "We just go through one crazy phase to the next crazy phase," Lifeson says. "When we went into the studio, they had a satellite dish. And late afternoon, they had The Big Valley, The Rifleman, and Bonanza all in a row. You know - Miss Barbara Stanwyck. So somebody went out and bought a bunch of cowboy hats, and we'd all sit around," he says, going into a heavy Western drawl, "talking like this. We decided when we went to England we'd take all this stuff with us. So there we were in England, in a 600-year-old house, and we'd walk through with spurs, satin cowboy shirts, cowboy hats, talking to the English housekeepers with 'Thank you very much for the vittles. We've got to be moving right along here.' And they thought we were crazy...this lasted for about three weeks. We'd play Patsy Cline every morning, and Ben Cartwright singing 'Ringo.' Do you remember that song?" Unfortunately, I do.

But all joking aside, Rush is intent on playing the kind of music they see as their own. Even if it means traveling to strange locations, learning new technologies or doing other sorts of strange things, the bottom line is holding the fire and staying true to their own musical ideals. It's an idea that they hope other young musicians will share. As Peart relates, "What matters to me is playing the music I like. So whether I make a living at it or whether I have to do another job to make my living, the point of honor is to keep the music good and pure. Straight from day one, young musicians have to make that decision in their own minds. And then they have to decide how hard they're willing to fight for it."

Rush has made the decision, fought the fight and won the battle. For them, the fire burns on.