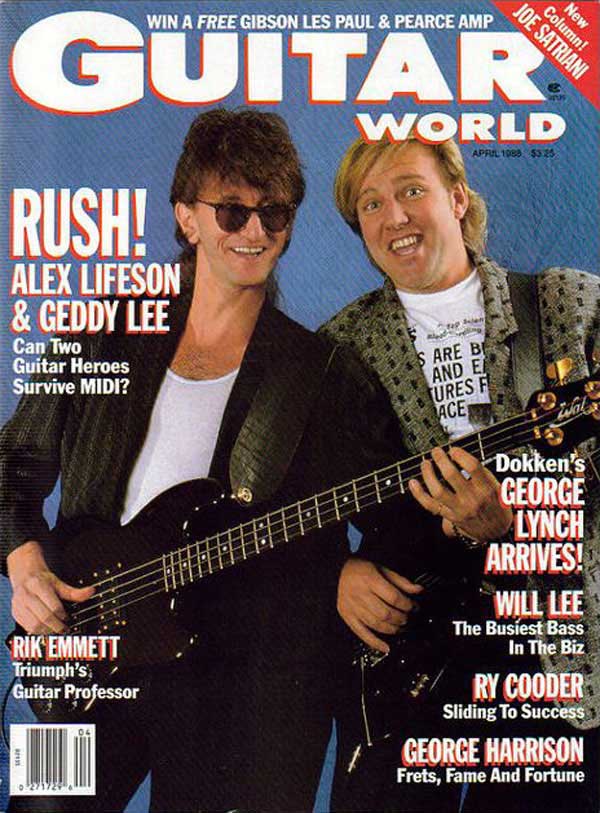

Alex Lifeson, Geddy Lee, Together Again in Rush

By John Swenson and Matt Resnicoff, Guitar World, April 1988, transcribed by Erik Habbinga

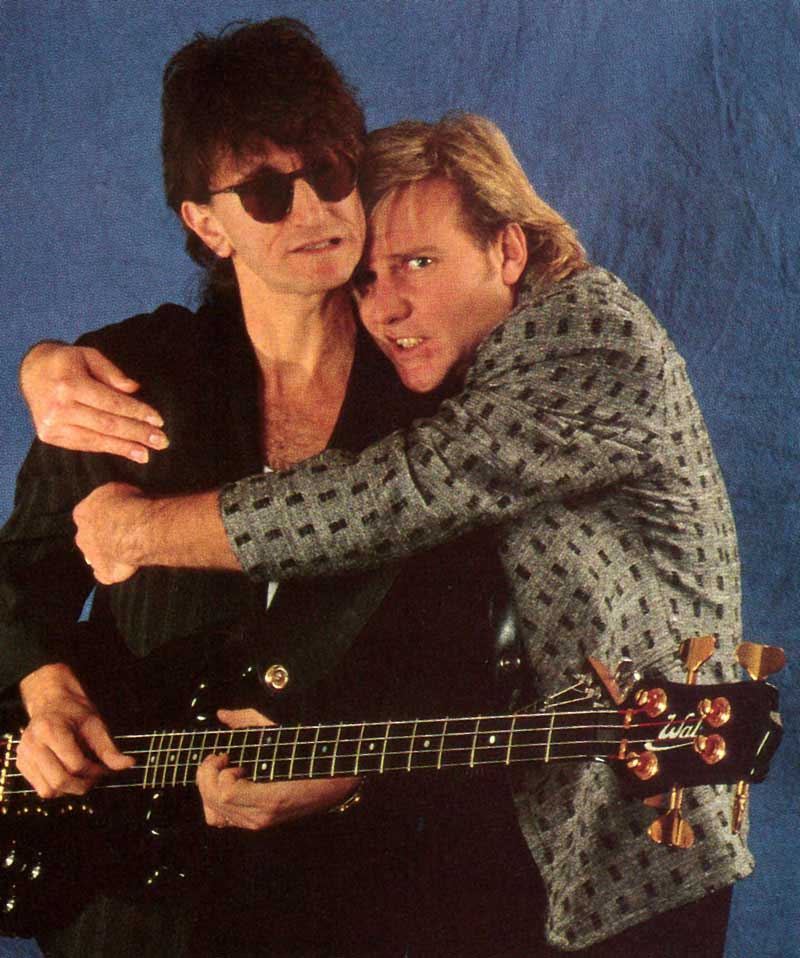

The power and the glory, ladies and gentlemen. We give you two-thirds of a power trio that continues to slay 'em in Sheboygan. But what's their musical bag these days?

The first snowfall of winter sweeps across Central New York driven by fierce Canadian winds, but it is another product of the northlands that entices rock 'n' roll fans off the farms on this blustery night to Utica's Memorial Auditorium.

Diehard fans of Rush, Canada's most distinguished rock band, mingle with newer converts in a minor league ice hockey arena turned rock festival for a night. After the McAuley Schenker Group completes an ear-splitting opening set, fans mill around looking for the best vantage point in the general admission house. Sightlines are important because Rush tours have featured filmed backdrop accompaniment for years.

Suddenly the house lights dim and a surprise intro - the Three Stooges theme, a zany variation on "Three Blind Mice"-blares over the public address system. The band launches into its set just as the theme ends and the crowd is on its feet for the better part of the next two hours.

The set is an intense. high-tech demonstration of the band's evolving arrangement strategy. The emphasis has moved gradually away from the power trio format that characterized early Rush toward densely arranged melodic slabs of sound played with surgical precision. Most of the set is drawn from recent albums. Guitarist Alex Lifeson plays with discipline and concentration despite the fact that his guitar sound is fluctuating wildly in the mix. On highlights like "Red Sector A", "Tom Sawyer" and several songs from the band's latest album, Hold Your Fire, Lifeson manages to slice through his technical problems with spirited playing.

Bassist-keyboardist-vocalist Geddy Lee is forced to concentrate even more. It's been a long time since Lee has been able to lay back and slam out bass patterns - he's doing three or more things in order to evoke the complex textures of the recordings. The rewards are there on such lyrical excursions as "Force Ten", "Time Stand Still", "Open Secrets", and "Turn the Page" from Hold Your Fire.

Toward the end of the set, when the band returns to material from earlier records, Lifeson and Lee kick out the jams on extended guitar-bass raveups fired by Neil Peart's most unbridled drumming. The audience goes nuts.

The crowd reaction doesn't help the band's spirit after the show. Lifeson, a musical perfectionist who's constantly tried to refine his sound over the years, has introduced a whole new series of effects for this tour and is irate over what he perceived as a system breakdown during the set.

"Last night it sounded 98 percent right," he laments, "so I thought another few minor changes might make it perfect. Instead, everything fell apart. After struggling through most of the set, I gave up and went back to the old setup."

Lifeson's sidekick, bassist Geddy Lee, is sympathetic to his partner's plight. "Getting the perfect guitar sound is a never ending quest," he explains. "No matter how good the sound gets, a guitarist will keep fiddling with it, looking for something extra. It's a frustrating process."

"The temptation for me is to make it better," Lifeson explains. "It's not just to keep up with the latest thing. I just wanted it to be better. Actually, Geddy started this whole thing with me. He said, 'Why don't you get an AMS? It sounds great, so throw out everything else.' The T.C. Electronics 2290's, I think, come very close to the AMS. The frequency response specs out pretty much the same. While they're not a fraction of the cost, they're certainly cheaper than an AMS, and in live application they're great."

"The problems that I'm having now don't really have anything to do with the equipment, the effects that I have, it's with the switching system. The great thing with the T.C. Electronic equipment is that it's quiet and it's true. What's coming out of the unit is the same as what's going in."

"Although there are lots of manufacturers of that kind of equipment, I don't think any of them comes close to achieving the kind of performance of these particular units. I used Roland for a long time and I really liked it, and Yamaha and all that, but they don't quite make it compared to what this stuff does."

Lee, on the other hand, has avoided changing his bass set-up for years. "I tried to change my bass gear around," he admits. "I've been using the same bass gear and amps for years now. My roadie, Skip, and I said we'd better compare it, because there's all these new kids in town, all these new amps and stuff. We brought 'em in and compared 'em, but the old dinosaur beat 'em all out [see Axology]."

"They all sounded good, but there didn't seem any point to change just for the sake of change. The big difference for me is using the Wal bass this year, which is a much easier bass to get the sound I want out of. It's really great to play, really rewarding. I just feel like I play better on it, like there's more definition to the notes." When Lifeson and Lee began playing together nearly 20 years ago, things were a lot simpler. At the time, the hot new sound was Led Zeppelin. Five years later, when Lee and Lifeson asked drummer-lyricist Neil Peart to join up, Rush was a power trio that bore more than a slight resemblance to that British quartet.

But now, 13 years into a career that has made the group one of Canada's best known cultural exports, Rush is nothing like the heavy metal kids they once were.

"It doesn't seem like we've been together for 19 years," Lifeson says as he leans forward on a metal folding chair in one of the backstage rehearsal rooms.

Lee points out that he could never have envisioned the current incarnation of Rush. "After we made Hemispheres (1978), we might have said, "This is the point we wanted to get to." But now, every record is a surprise to me.

Few bands have mirrored rock's stylistic changes over the last two decades as effectively as Rush. From the early seventies heavy metal albums Fly By Night and Caress of Steel, the band developed a Pink Floyd like space music for the science fiction concert albums 2112, A Farewell To Kings and Hemispheres.

Rush dramatically altered its style on the 1980 album Permanent Waves. All the arrangements were tightened up as the record moved away from the concept approach in favor of shorter, thematically unrelated songs with clever melodic hooks. Suddenly Rush was commercial - "Spirit of the Radio" was a hit single and is now one of the most recognizable anthems in the live show.

Then, with Moving Pictures, Rush began playing with more complex arrangements as the individual players adjusted to the sophisticated musical climate of postfusion rock, where ideas that would have been classified as jazz in the past are now routinely assimilated into rock arrangements. Rush sounds like nothing so much as a fusion group on Grace Under Pressure, Power Windows, and now Hold Your Fire.

"I don't know," Lee said. "I guess it's closer to fusion than anything else that's around. We just don't seem to fit into any category anymore."

"It's certainly closer to that," Lifeson added, "than Bon Jovi or Cinderella."

"I think it's more melodic," Lee continues. "I was listening to the opening act on the tour [Michael Schenker], which is sort of like a metal band, and I was thinking how far we've come from that. Just in comparing soundchecks."

"You hear all these melodies and all these vast arrays of notes that we're playing now and compare to the harmonically limited style of metal; that's when I feel like we don't fit into that category anymore, that's when I feel more closely aligned to something like fusion. If not so much the immediate sound of it, than the attitude, a search for notes. That's the most exciting prospect of being in this band, the compositional challenge.

"I think the writing stage is the most important, and everything else revolves around that. I don't think that was true 10 years ago. It was playing then, but now I look at myself more as a musician in the compositional sense than a musician in the playing sense. This is the part that makes it really worthwhile, why I still do this.

"I definitely wouldn't be doing it if it were still just Led Zeppelin takeoffs. As much as I love to play, if you're just gonna play, it doesn't have to be like this. There's a million ways to play. I love those two hours when we're onstage, but everything else associated with touring I don't really like that much anymore. But there's a great satisfaction when you walk offstage after a great show and the crowd is responding and you know you've played well enough to deserve that response. It doesn't always happen that way. It's a great feeling when it does."

Lifeson agrees with Lee that the songwriting process has become the most rewarding part of the band's routine. "The greatest feeling is to write a good song." he says.

Lee goes on to describe the band's painstaking method of constructing songs. "First, we all work on little bits and pieces on our own," he explains. "Alex and I have a writing complex which we use to save time. It's a matter of happenstance whether the music or Neil's lyrics come first. If he has lyrics, he gives them to us, otherwise we have the music first."

"It's become a lot more efficient in the last few years," Lifeson adds.

"Every year, we take more and more time to write," says Lee. "This year we took two months just to write the demos. We work every detail out before we go into the studio. The more records we make, it seems to make sense to do that. We have that time to concentrate on our songwriting and we realize how important that is to us."

"In the old days, we used to write on the road, in cars, dressing rooms, wherever we could get 10 minutes. We couldn't take two months off to record, or we wouldn't be able to survive."

Lifeson works out melodic fragments and ideas for songs on his own in a portable home studio. "I have this Teac eight-channel tape recorder," he said. "I set up a little studio in the basement. It's a good little exercise. You set up a drum pattern, and I have a guitar synthesizer so I can put on different lines, a bass line, a string line, and I have an Emulator down there which I try to use as well. I try not to get too caught up in the gadgets. I just try to get the basic ideas down, like bits of songs, a chorus or a verse - not whole songs."

"We work in so many different ways," Lee points out. "We record all of our soundcheck jams, and we jam at every soundcheck. At the end of the tour, I'll take them all home and catalog them. Whatever ideas I think might be good for verses, choruses, I'll develop. Instrumental, wild jams, a lot of them are just good for what they are; you can't get a song out of them. Some of them are just great spontaneous energy, and you can hear how pissed off you were that day, but a lot of them are really good starting points for songs. We write together, so a lot of our ideas start out together like that."

"A lot of times we'll arrive at different times for soundcheck. Once a tour gets going and the gear gets up quicker and quicker, you start coming in a few minutes earlier and just jam for 20 minutes or longer, them we'll do our regular two or three songs to check everything out. You get really frustrated playing nothing new by the end of the tour. A few years ago, we realized these jams were good, then it just sort of became a way of writing, now it's a matter of course, 25 cassettes at the end of the tour. We never discuss what we're going to play in advance - we just break into it, basically thinking out loud."

Several moments on "Hold Your Fire" originated in those soundcheck jam sessions. "Open Secrets' was like that," Lee says. "The main bass riff that opens up "Turn the Page" came directly from a jam. The main ideas are spontaneous. It's the final arrangement that you sort of hone and craft, but the initial burst is some kind of spontaneous energy."

Lifeson explains that those tapes form the first part of the songwriting process, but are soon eclipsed by a more hands-on approach. "We spend a couple of days going through the tapes, but a lot of it is just Geddy and me sitting down together, playing for about an hour, and the ideas just come out. We say, "Let's put that on tape", or "Let's develop that.""

"I like going through tapes," Lee agrees, "if were stuck or if we're looking for something specific, but I like to start fresh, especially if we have lyrics to work with."

Lee sees Hold Your Fire as a potential turning point for the band. "I feel really good about the album," he claims. "This album says something different to me from the last few albums. It marks a point to me that almost says we are a different band than we were. Every once in a while we do a record that says to me we're evolving into something. This is an arrival record, like we climbed up a hill and now we've gotten to the top and we have to decide where we go from here. At the time we did Power Windows we thought that was the kind of record that was, but it never felt like it afterwards. We learned a lot; it was an arrival in terms of production, but not in terms of songs, and I think this record is, in the same way that 2112 and Moving Pictures were.

"There are very few records that sound really cohesive, and this one has that," says Geddy. "I think that's because we've put so much effort into our songwriting. To me, it's a miracle every time I can sit down and write a song with Alex and Neil -yesterday it wasn't there and now it's there. I just feel so proud that we can do something that's worthy enough. At this stage when we work on something hard enough, and it's a part that's good, we all know it's good. I just feel really rewarded, like it's what I'm here to do. This is the part that makes it really worthwhile, that makes me want to keep doing it."

When Lee and Lifeson began playing together nearly 20 years ago, they were taking their first steps not only as ensemble players, but also as individual musicians on the threshold of cultivating highly recognizable playing approaches. Time has seen that virtuosity meld into two highly complementary musical sensibilities. "I guess my first real bass influence was Jack Bruce," recalls Lee, "just his aggressive style. Very rarely did he have your basic, standard, mellow bass tone. His sound was very aggressive, almost distorted, and as a result he stood out when he would wander around the neck; there was constant action on the bass. Being in a three-piece, his role as a bass player was to be very busy and take up a lot of space. Then came John Entwistle, who's very bright and toppy, and had an aggressive style that was very important to me as well."

While many contemporary lead-bass players rely in great part on thumbing and snapping, Lee remains faithful to his rather singular fingerstyle, using three right-hand fingers to blend percussive snaps with powerful and complex lines. "When I snap and pop my strings, I don't use my thumb, I use my fingers. On the right hand, I use three fingers a lot of the time and if I do want a brighter, harder sound, then I'll use one finger, and I'll use my fingernail to get a little more edge on the string. I know Entwistle used a pick from time to time, but I never felt comfortable using one - I just used my fingers. Everyone used to say you can't get that bright kind of snappy sound without a pick - not true. That's my sound, the style I went after. I think Entwistle wasn't using a pick on some of the better things he was doing anyway, but his influence held me until Chris Squire came along."

"In the last few years, the person I admire most as a bass player is Jeff Berlin, whose is quite a different style. The kind of fusion he plays stands because he's got a rock sound. He can play the jazziest lick, but he'll play it very aggressively, and I think that's what all those players have in common, and what has helped me develop my style of playing." One of the biggest problems posed by the increasingly complex song structures developed by Rush is reproducing the material on stage. Since the band is a trio, the interlaced synthesizer parts have to be triggered during the performance.

"Mostly I play the keyboards and synth parts," Lee says, "but what happens is that by the time you get to the tour, there's usually such a heavy workload of synths and sampling and triggers and sequences that I can't handle it all. There are moments when Alex doesn't have that much guitar to play, so he's doing more and more of it."

"There's two schools of thought," Lee explains. "You can look at the arena as a different interpretation of the same song, or you can try to interpret it as accurately as possible. That sort of haunts us, because the challenge now is 'Can we pull it off?' At the same time, it's limiting because you can be trapped by all these pedals and sequencers."

"I prefer the song as it was recorded," Lifeson notes, "but as Geddy says, it can become restrictive. You're standing in one spot, and both feet are going." When Geddy goes for the keyboards, Alex keeps the bass line going on foot pedals.

"It's a real concentration game," Lee says, "a real choreography in a way. When there's a song where you don't have to do that you can really let it all hang out. You can run all over the stage."

"That's the great thing about the end of the night," Lifeson laughs, referring to the encore section, where seriousness and arrangement are thrown to the wind, and the lads do a lot of fooling around on stage. "The last few songs we do are all old songs, there are no synths, and we go mental. We have fun, laughing, singing stupid lyrics."

Although the trio has enjoyed the loyalty of a rather diehard following that discovered the band through the sophisticated guitar/bass/drum interplay of their early to mid-seventies work, a number of the band's critics have yet to come to terms with the transmutation of their sound. The chorused, spacious guitar splashes against Lee's obese synth-bass foundation are a far cry from their gritty, odd-time excursions of yesteryear. The change sits well with the band, but not that well, as Lee explains. "I'm constantly torn between being a keyboard player and a bass player. I don't really consider myself an accomplished keyboard of any kind, and keyboards have always been sort of a necessary evil for me. I enjoy playing them, but they've always detracted from my bass playing, and I consider myself a bass player first. Arrangements in the past have always been such that wherever there was a keyboard part happening there would usually be a bass pedal part, and when the keyboards stopped, I could jump in with my bass. Usually I tried to overcompensate by being as busy as I could [laughs]! On the last record, we said, 'What the hell,' and we had the bass almost consistently through, with the keyboards as well, and we dealt with it. Alex is taking some of the keyboard responsibility from me onstage, and this frees me up to play a little more bass. But as far as our style of playing goes, that type of riffing we used to do, I think its just a natural evolution. We have that ability to throw in those kinds of riffs when we need then; by no means have we forsaken that style of bass/guitar duet kind of riffing. There's always room in our music for that kind of thing to come back.

"You go through phases of learning about yourself as a writer," Lee continues, "and compositionally, this where we're at now, using those spacious chords and that type of arrangement. I think it's very important for an artist/musician not to limit himself at something even though he does it very well. He has to push himself into different areas and learn how he plays in that style, and discover what benefit that is in his compositional repertoire."

The years may have given Rush perspective, but not a clear distinction between album and album, tour and tour. "It starts to run together after awhile," Lee admits. "It's sort of been a gradual change. This tour feels different. The selection of material is more new-sounding Rush and a lot of the older things, a lot of the older vocal styles particularly have fallen by the wayside. It's getting a more relaxed feel to it this tour. Musically, it feels richer. That's one thing I've been feeling about the last few gigs."

Rush has been around long enough and changed dramatically enough that the band has lived to see a host of copy groups playing on its past glories. "We hear about them all the time, and it's weird," Lee says. "There's a band back in Toronto that claims they sound more like us than we do. It's just such a weird thing to say, a weird thing to think about. I think they're called Void. They play the older stuff. Their attitude is they're more faithful to our sound then we are.

"It's like these bands come out, on the first and second record you can hear a sound developing, then on every record after that, they seem to be imitating themselves. That's real disappointing. It's like athletes talking about themselves in the third person. I've never gone into the studio and said, 'I need a Geddy Lee sound for this part.' There are certain things that do repeat, and that's what a real style is - instinctive repetition. But when you're making a concerted effort to repeat yourself, that's when things go bad."

Geddy's Chain:

According to Skip "Slider" Gildersleeve, bass technician with Rush for almost 13 years, Geddy Lee's rig remains "pretty basic." Lee is currently operating two systems, Systems B and C, and either's selection is dependent upon the bass needs of a given moment. System B runs a four-string Wal bass through a Telex wireless unit and into a Furman preamp. That signal is processed through an API 550 unit and fed into a custom switching box which directs it to Geddy's choice of two BGW amplifiers driving an Ampeg B4B bass bottom and a miked Tiel double 15 cabinet. "The Ampeg cabinet is the oldest thing on stage," Skip notes. "On this system, a Boss eq pedal is used as a boost for solo sections, but only about three times during the set, for when he goes up the neck."

Lee runs the Steinberger four-string bass through System C, which - except for the lack of a Boss eq - is identical to B. "if he breaks a string on System B," Skip explains, "all I do is hit system C, pass him another bass, and he's off and running." On both systems, DI's are taken right off the pickups, between the wireless and the preamp.

Although both systems are fully operable and accessible, Geddy has relied on System B, the Wal system, almost exclusively for the Hold Your Fire tour. He finds that minor adjustments in technique, combined with the inherent qualities of the Wal instrument, afford him the most control over his sound. "You get a stronger, tighter, twangier sound," Geddy explains, "if you pluck back by the bridge, and you get a different kind of top end when you play over the pickups, and I've found that that's very important to me, moreso in live concerts than on records. I'd rather play around with that than change eq's drastically onstage."

"I like both Steinbergers and Wals a lot," he elaborates. "The Steinbergers with the new eq's are really good, and it was a very difficult choice for me as to which bass to use for this tour. When I started using the Wal, I used it almost exclusively on the last record [Power Windows] because the recording engineer I was working with found that he could get a great sound with it very easily. When it came to playing live shows, I wasn't sure which bass I was going to use. I started playing the Wal, and our concert sound engineer said the same thing, that there's something in the midrange sound of that bass that makes it easy for him to get it to sit in the mix. Plus, the width of the neck is a little greater, and somehow, I was playing a little quicker on it. I fully intended to use the Steinberger during the show, but what's happened is that I've just gotten so comfortable using the Wal, and I've got so much on my mind during the show as far as keyboards go, that I can't be bothered to change. It's also quite a change from the big Wal neck to the slimline neck of the Steinberger, so right now I'm using the Steinberger as a backup, but not because it's the lesser of the two." Lee also owns a five-string Wal which he played on the track "Lock and Key" [Hold Your Fire]. "It's a very difficult bass to play," he says, "and it's not something I plan on using a lot because it's really heavy and cumbersome, although it enabled me to get quite a different sound on that track, and get a different perspective on the bass."

What happened to System A? "That used to be a stereo Rickenbacker system," Skip notes. "Part of the reason Geddy abandoned it was that it was stereo, and we didn't want to bother with stereo transmitters. Also, the Steinberger was not only a good bass, but also good for portability, for playing around keyboards and three mic stands."

"I loved the sound of the Rick for years and years," Geddy recalls, "but I think I got a little bored with it, and that's why I started using the Steinberger. The sound of the Steinberger really impressed me, and at the time I was starting to use more keyboards, and the Rick was very awkward onstage. I just grew away from it, into a slightly more complex, warmer sound. Now, with the Wal, I've got a combination; the twang of the Rick, but with a warmer, almost funkier lower midrange and bottom end."

Every two gigs, Skip replaces the Wal's Funkmasters and the Steinberger's La Bella Hard Rockin' Steels with custom-gauged sets measuring .030, .050, .070 and .090, high to low. "New strings are Finger-Eased, heavy duty, with a towel, so that they don't squeak."

Although Lee operates an extensive keyboard set-up onstage with Rush, Skip keeps a safe distance, concerning himself only with the bassics. "The bass stuff is easy, and Alex's guitar stuff is kind of complicated, but the keyboard stuff is unreal. They've got nine Akai samplers, some [Yamaha] DX7's, MIDI routing...I call the bass system the 'dinosaur' because I've had it for years and years. We've had parades of amps come through rehearsals; all kinds of stuff came and went, but we stuck with this."

Plus ca change...

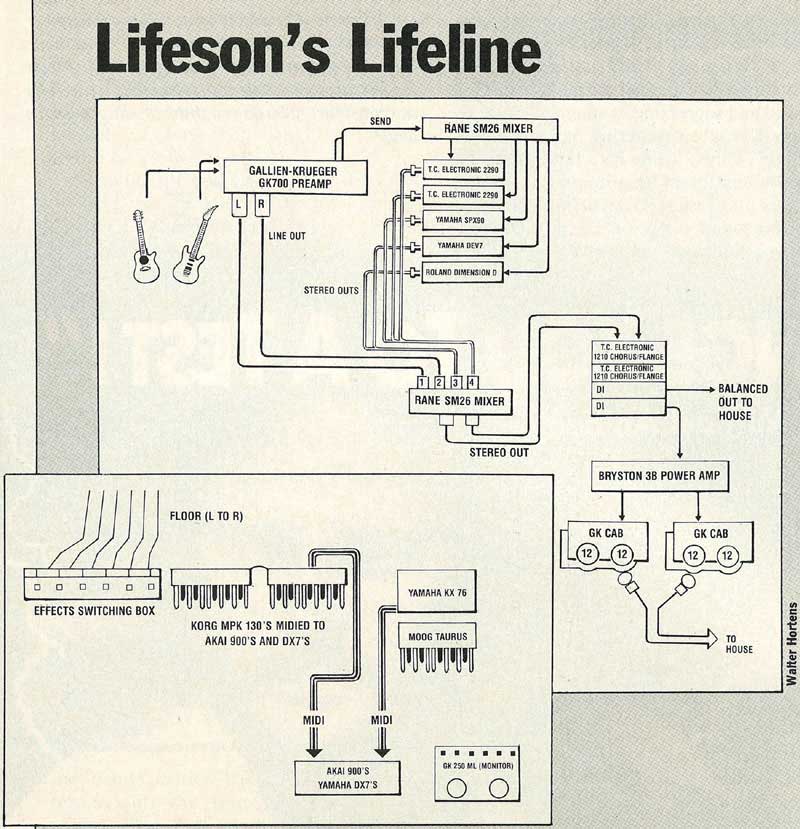

Lifeson's Lifeline:

Alex Lifeson is carrying only five guitars with him on Rush's Hold Your Fire tour. His four solid bodies are custom made by a Canadian company called Signature, and each is equipped with three active single coil pickups and a locking tremolo system. One of the Signatures is tuned up to F# for the set's opening song, "Big Money," and an Ovation 1985 Limited edition six string acoustic is mounted on an Omega stand for the intro to "Closer To The Heart."

In their quest for the optimum guitar sound, Alex and guitar technician Jimmy "J.J." Johnson have been experimenting with a variety of effects. Alex's current guitar setup finds his signal transmitted from a Nady 700 wireless system to a Gallien-Krueger 2000 preamp. The preamp's send signal is split five ways by a Rane mixer and fed into two T.C. Electronics 2290 digital delays, a Roland DEV 5 and Dimension D and a Yamaha SPX90 effects processor, which are controlled by an SES switcher. The preamp's line out, along with the effect's stereo outs, feeds another Rane mixer, where the wet and dry signals are channeled into stereo. That output is choursed and flanged by two T.C. Electronic 1210s, and D.I.ed to both the house and a Bryston power amp. "It's probably unique that a guitarist would use one of these amps," J.J. observes, "as it's used in a lot of studios as a recording amp." That amp's parallel input drives four GK 2x12 cabinets, two of which are miked by a Sennhheiser MD 421.

Lifeson operates his two racks with a custom pedalboard which includes an on-board switching system for the GK preamp's chorus, compression and gain functions. His floor system revolves around a set of Moog Taurus pedals and a pair of Korg MPK 130 pedal units which are MIDIed into an offstage bank of Akai 900 samplers and Yamaha DX7's. These samplers are also accessed by a Yamaha KX76 MIDI controller keyboard, which, along with a second set of Taurus pedals, is removed from the stage after the song "Time Stand Still." A GK 250ML is placed far stage right and serves as the technician's monitor.

The Signature guitars are strung with Dean Markleys, gauged.009, .010, .016, .028, .038, .048. The Ovation uses Markley medium light bronze. Like Geddy, Alex is a fan of Finger Ease string lubricant. "Cases of it," laughs J.J. "It's all he lets me use."