Visions

The Official Biography

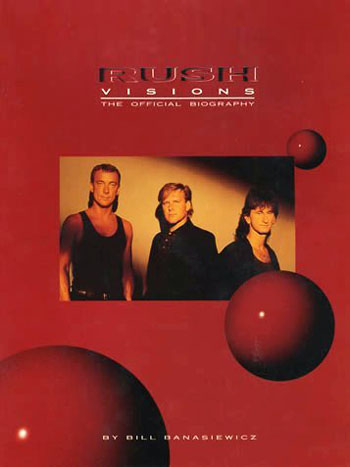

By Bill Banasiewicz, 96 pages published April 4, 1988 by Omnibus Press, ISBN 0.7119.1162.21988

"Over the course of 16 albums and thousands of concerts throughout the globe Rush have established themselves as the most popular heavy metal and progressive rock trio in the world. Their unique blend of power rock and intelligent lyrics has won them a following as devoted as any in rock.

"This first and only official biography follows the career of Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart from their earliest days as a Toronto bar band performing cover versions of sixties rock to their most recent LP 'Hold Your Fire'. Along the way Rush have faced critical indifference with an uncompromising stance that has justly increased their popularity."

Chapter 1

© Bill Banasiewicz

Reprinted by Permission

All Rights Reserved

In 1968 psychedelia ruled. Flowers and guitars, protest and imagination, dominated the airwaves and the headlines. While students around the world tried to change politics, musicians expanded the way people listened. Along with the gentler strains of The Beatles, Donovan and The Byrds, another type of music was making itself heard. Bands, mainly from England, sang about young men's blues, strange brews, and being experienced, over the sounds of bass, guitar and drums. Groups like The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Who and Cream all shared a mixture of speed, aggression and feedback.

Thousands of kids in basements from Great Britain to the United States and Canada were occupying their time trying to emulate these new sounds.

To a 14-year-old boy who played in the basement of his house on Pleasant Avenue near Yonge and Steeles Streets in the Northern Toronto suburb of Willowdale, many of the events of the late 1960's were far away, but the feedback was as immediate as the nearest amplifier.

Alex Lifeson, the son of Yugoslavian immigrants, had been playing guitar for two years. He was given a $13 Kent Classical for Christmas in 1966 and the strings felt natural to him because he had already practised with a viola and a neighbour's guitar. The first tune that emerged from his guitar was the jingle to a Noblesse cigarette commercial.

Born in the mountain town of Fernie, British Columbia, just north of Glacier National Park, his family soon moved to Toronto, into one of its many ethnic neighbourhoods.

When his good friend John Rutsey, who lived across the street, began banging around with the drums, the two started playing together. At first John used a rented kit, but eventually his parents relented and bought him some battered second hand Slingerlands. They shuttled back and forth between each other's basements depending on whose parents were willing to put up with the noise that week.

Other area kids soon joined in. Basement bands were formed. There was a whole bunch of kids who would hang out together, listening to the music and carrying equipment when needed. The first band formed by Alex and John in the Spring of 1968 was called The Projection. By the end of the summer that band had broken up.

In August, Jeff Jones came in as bass player and lead singer and a formal line-up of John, Alex and Jeff was formed. They spent their evenings and weekends trying to learn the hard rock songs of the day and scheming for an opportunity to play outside their basements.

The boys were soon able to work out an agreement to play in another basement, but this time they would be paid. Their salary was $25. The gig consisted of playing on Friday nights at an oddly named coffee-house located in the basement of an Anglican Church. The Coff-In served coffee, doughnuts and music to local teens for 25 cents a head.

The band was excited, but they had a big problem. While they had been dreaming of playing, they had neglected to come up with a name for their group. So a few days before the gig they sat around in John's basement trying to come up with an appropriate monicker. They weren't having much luck when John's older brother Bill piped up, "Why don't you call the band Rush" and Rush it was.

The Coff-In was one of many so-called drop-in centres sprouting up in Canada at the time. By telling friends and acquaintances about the gig they were able to draw in nearly 30 people for the show. They were received pretty well, and with one live performance under their belts, the members of Rush were ready for a return performance. Well, at least two of them were.

The following Friday saw their new-found careers almost come to a halt. At around 5pm, just a few hours before they were due to perform, Jeff called and cancelled because he wanted to go to a party. It was time for some quick thinking, so Alex called up another bass player he had jammed with a few times.

"Often I would call Gedd up to borrow his amp. When I called him up this time, right away he thought, 'Oh, he's going to want my amp', and I said, 'Do you think you could come and play with us, because Jeff isn't coming, we don't have a bass player, and we have this gig tonight. We'll just play the songs'."

The songs consisted of half a dozen Cream tunes that most of the neighbourhood players thought they knew by heart.

Alex later told Geddy that he would have to sing. Geddy was not thrilled about this, but as the new man on board and with lead singers hard to find, he didn't have much choice. Alex had first met him in a history class at Fisherville Junior High. Their history teacher, Mr. Bissle, remembers Alex as being "very likable, fun, outgoing and level-headed. I always had Alex sit right in front of me where I could reach him. Gary (Geddy) was more quiet and studious. He had his feet on the ground and was soft-spoken. The two of them would sit around the school playing their guitars all the time."

Geddy was excited if a little surprised by the request. He had never met John. "Alex used to borrow everything," says Geddy. "He borrowed my amp regularly and one day he called up to borrow me."

Gary is from a family of Polish Jews who survived the war and moved to Canada to start a new life. The name Geddy comes from his mother calling him Gary in a heavy Yiddish accent, which of course sounds like Geddy, and the name has stuck ever since.

Geddy had started out on guitar, an acoustic with palm trees painted on it. The first song he ever learned was 'For Your Love' by The Yardbirds. He switched instruments when his first band lost its bass player and the group elected him to lose two strings and fall into the rhythm section.

Geddy's debut with Rush in September of 1968 was solid. When they had exhausted their repertoire of the half dozen Cream songs they knew, they played them again, and then again.

After the show the trio split the $25 and went out to eat. At the restaurant they decided Geddy was in, and Jeff was out. Their first rehearsal was set for later in the week. Jeff was already playing in another band (Lactic Acid) so his dismissal was not that big a deal at the time.

When the new version of the band assembled for practice they had a rather motley collection of equipment. Along with borrowed amplifiers and other gear, they had a few things of their own. John had his Slingerland drum kit, Alex a Conora guitar. He bought the Japanese solid body for $59. Geddy also had a Conora.

"I painted my Conora bass myself. It had all these beautiful colours on it. In those days, Cream were my heroes, and Eric Clapton had this guitar that was beautifully painted, so Alex and I thought we'd paint our guitars."

Rush rehearsed as much as possible. They slowly expanded the number of cover versions they did, and tunes by Jimi Hendrix, The Who, Jeff Beck, The Rolling Stones, Blue Cheer and Elvis joined the original set list of Cream songs. Perhaps the most unusual song in Rush's sixties repertoire was Presley's 'Jailhouse Rock' sung in Yugoslavian! The band also began writing original material. The tunes usually didn't even have names; they were mostly 12-bar blues, simple in structure, almost glued together with plenty of room for solos and hollering.

The first composition that got a name was titled 'Losing Again'. Geddy and Alex wrote most of the music with an occasional contribution from John. The lyrics were made up on the spot.

"On 'Losing Again' Alex and I kind of hammered it out," John remembers. "I had an idea, and I didn't play a melodic instrument, so I kept repeating to Alex verbally what it should sound like. I had this song running through my head and I couldn't play it. We worked it out together and finally it sounded like it did in my head. That was our first song."

But with most of the songs, "Gedd or Alex would come in, have an idea and they'd start playing," says John. "They'd have a riff, or a chord, or a few bars of something and we'd all go 'That sounds good'. It would then be practised and we'd stop and say, 'Let's put this little bit in here'- that sort of thing. It was not unusual that somebody would have a complete concept of a song, a beginning, a middle and an end. The first song someone had totally written out was 'In The Mood'. Gedd came in and said, 'I've got a good idea for a song' and played it from beginning to end."

Rush continued playing with borrowed equipment at the Coff-In. For one show Alex managed to convince his friend Nancy Young to borrow her brother's Gibson Firebird guitar. Her brother Lindy came along for the November Coff-In show. Everyone was quite impressed as Lindy began fooling around on the piano. He met Alex, Geddy and John and eventually started hanging out with Rush and their friends.

Rush began to gig at other drop-in centres and high school dances which could pay as much as $40 for one night's work. But a lot of the band's playing was still confined to each other's basements.

Geddy's brother Allen says, "The rehearsals could have an unintentional comic note. My grandmother would be yelling about the noise and the band were playing so loud they couldn't hear her. They just kept jamming while she kept yelling and cooking."

Since volume was as important as skill, the band could be heard for blocks around. Allen would catch neighbourhood kids sitting outside the basement window and chase them away. Many of these kids would later show up at the Coff-In.

On Christmas Day 1968 Alex phoned Lindy Young and asked him to join Rush as keyboard player. He agreed and they rehearsed at Geddy's house every day during the holiday break.

"Rush was not a heavy metal band," recalls Lindy. "We were more like a blues/rock band. Geddy was singing in a low register and had not even thought of singing falsetto."

The four-piece Rush debuted the first week of January 1969 at the Coff-In. The show featured cover versions of songs by Traffic, Willie Dixon and Ten Years After. The band was beginning to evolve with Lindy's electric piano and vocals, according to John Rutsey.

"Lindy was a real good musician. In addition to keyboards, vocals and guitar, he played harmonica and drums on the side. He was a fine musician and the band evolved musically with his addition. We were really trying some different things for the time. We were getting into early Grateful Dead and things of that sort."

Throughout February 1969 Lindy began playing more guitar and singing with Rush. 'You Don't Love Me' by John Mayall which Rush covered, featured lead vocals from Lindy. The band were on a roll into March and April. They were the main band at the Coff-In and Alex was really coming into his own on guitar. The future seemed bright even at this early stage. Bright that is, until John convinced the others that Geddy's spotlight should be turned off. So in May Geddy was kicked out of the band. Alex, John and Lindy got Joe Perna to play bass and sing and the name Rush was changed to Hadrian.

Hadrian practised in Lindy's basement with a new admirer looking on, someone who would prove crucial to Rush's later success. Ray Danniels had frequently stopped by the Coff-In to hear Rush, so when he heard of a new band formed from Rush he insisted on booking them. He was 16 at the time and already an aspiring rock mogul. He even had a small booking agency named Universal Sounds. He produced shows at local high schools and drop-in centres.

"Ray was enthusiastic, talkative, a salesman type of guy," remembers John. "He asked us if we had an agent and we said, 'Of course not.' So we went in with him and he started to get us a few jobs here and there."

Ray soon became Hadrian's manager. "They were a part-time band playing in basements," he recalls. "But even then they were writing original tunes. That was the thing that separated them from the rest of the bands at the time."

In June Geddy founded a rhythm 'n' blues band called Ogilvie. He was actually having more success with his band than Hadrian. Gedd will never forget going to a Hadrian gig to help Lindy out with the words, since he now had to sing lead on most of the songs. He went to the Willowdale church instead of going to see the last Toronto performance of The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

During July Ogilvie changed their name to Judd. Ray Danniels was also booking shows for Judd, but unlike Hadrian, Judd were getting lots of work. In that same month Lindy quit Hadrian and joined Judd. Hadrian's last gig was at the Willowdale United Church. Joe Perna didn't play all that well, so when Lindy left they disbanded.

Geddy and his band Judd continued working hard right through the summer, while Alex and John were in limbo. They didn't know what to do. Finally in September Judd broke up. John phoned Gedd and asked him to reform Rush. Gedd agreed. Lindy was beginning studies at Seneca College so he didn't rejoin. He was also tired of performing; while he liked playing at parties, he was not as serious as the others, and they were now very serious.

During the autumn of 1969 while hanging out at Al Denokowski's house everyone was blown away by the first Led Zeppelin album, especially Alex, Geddy and John. They were amazed at the sound Jimmy Page achieved on a recording. Zeppelin, the prototype heavy metal band, built on the hard rock sounds of The Yardbirds, The Jeff Beck Group and Cream, but they managed to make their music thicker, harsher and louder than anybody else. The style entranced Rush and they soon began trying to emulate Page's unique style.

By November 1969 Rush were playing heavy rock, Alex with a stack of G.B.X. amplifiers, Geddy with a double stack of Sunn amps. He was also starting to sing like Robert Plant, developing a piercing falsetto.

Lindy Young jammed with Rush in their basements once again, but this time they were playing so loud he couldn't hear his electric piano. "If you want to be in this band, " said Alex, "I think you're gonna need a bigger amp." Rush were obsessed with heavy music and even their original songs took on more of a Zeppelin-like tone. Ray Danniels began dreaming of Rush as the next Led Zeppelin.

Alex, John and Geddy resumed gigging at the Coff-In where their playing improved and more people began to take notice. Orme Riches, who ran the Coff-In at the time, later told Toronto's City Magazine about the way the band built up its audience. "At first there was just 40 or 50 kids, but as word on Rush spread attendances soared up to 300 in a space that could comfortably hold half that number. Kids from all over the city came to see Rush swamping out the locals."

This success backfired because the ever increasing number of people coming to the shows eventually caused the Coff-In to close. Church officials thought things were getting out of hand.

Ray worked hard at getting other shows for Rush, but it was difficult to find work for a power trio that did so many original songs. Sometimes at high school dances they found that their brand of hard rock did not go over well with teenagers eager to dance to the latest Creedence Clearwater Revival single. Kids would shout out "Play some rock 'n' roll." John remembers screaming into the microphone, "We're not playing fucking jazz!" One song in particular, a Rush original called 'Child Reborn', almost always drew a hostile reaction for its complex tempo changes. The band even threw a bit of 'Hava Nagila' into the number.

"You can imagine how this sort of thing went over in front of high school kids wanting to hear Top 40 tunes. It got rough at times," says John.

So the band took on odd jobs to support themselves. Alex pumped gas and worked with his father as a plumber's mate, while Geddy worked in his mother's variety store and as a part-time painter. Alex and Geddy were also still going to school. John had dropped out. All three were under pressure from their parents who were beginning to suspect that their sons might actually be planning to make music a career, not just a hobby, which was something they could not accept.

Ray's efforts at getting them gigs began to get more successful, but occasionally these shows would be some distance from home. "They'd get out of school at three o'clock," says Ray, "and drive like hell to get where they were going. They would play high schools in Sudbury, North Bay, Cochrane, Kirkland Lake, London, Deep River and Windsor, Ontario. These cities and towns are anywhere from 200 to 500 miles from Toronto, so it was a pretty hectic schedule for kids who were going to school."

But for the guys in the band it was anything but a chore. Alex couldn't wait for the school bell to ring on the days when they were going to play. "I remember it being great!" says Alex. "We'd finish school and everyone would make their way to where the band was leaving. Doc Cooper lived across the street and most of the time he would drive us to gigs in these old beat-up limousines. We also had another guy, Larry Bach, who drove his car, and we'd put a U-haul trailer on the back with all the gear in it. We played all over Ontario and we loved it."

Rush usually played by themselves at these shows. The performances consisted of two one-hour sets or three 45-minute sets. The band played original compositions such as 'Number 1', 'Keep In Line', 'Run Willie Run', 'Mike's Idea' and 'Tale'. Also thrown in were the ever-present Cream, Hendrix, Who and Zeppelin covers as well as other hard rock hits.

As many as 200 or as few as a couple of dozen people would come to the shows. John was the band's front man, although he didn't sing. He would introduce songs and talk in between them. The stages were usually set up in high school gyms.

"There were some gigs we played in Northern Ontario where kids were lined up against the wall," says Alex. "At other times only 35 or 40 people would come to a dance, pretty dismal! Around Toronto we did pretty well, selling out to 150 or 200 people. Up north it took a couple of years before the band really got going."

Throughout 1970 Rush continued gigging and working on original material. They composed 'Sing Guitar', 'Morning Star', 'Margerite', 'Feel So Good', 'Love Light' and 'Garden Road' during this first year of the new decade.

In February 1971, the group again gained a fourth member. Mitch Bossi joined as second guitarist. Bossi, later told City magazine that he was a mediocre musician who was more interested in having fun and wearing flashy clothes than in making music. He only stayed with the band a few months. He told the magazine that he quit because the others took it all so seriously. He added, "I didn't see too much future in the band. They were a different kind of people to me. They didn't worry about security, they thought everything would turn out all right." They were right.

During the late spring the band was helped by a new provincial law. The Province of Ontario lowered the legal drinking age from 21 to 18. This opened up a whole new range of possibilities for Rush. They could now legally perform in bars, although it wasn't easy to find a place that would hire them.

"I remember the first bar gig," says John. "It was really something else. We were suburban kids. None of us had really gone out drinking in bars. Ray got us a job at the Gasworks. I was petrified because this was playing for grown-up people. Everybody in those days had really lame equipment when you come to think of it. Terrible stuff. Cornball lighting, Christmas tree lights like you use in your front yard. Ian Grandy and the other roadies would painstakingly put it together. That guy did a lot of work for the band. He also helped us out at that first gig. We played really low because we thought the audience would throw beer bottles at us. We got a kind of muted reaction during the first set. Ian came up to us and said, 'Turn it up'. I was really shocked. So the second set we took his advice and went over pretty well."

The band's insistence on playing original songs caused problems for Ray. During the summer of 1971 he was able to find them only three gigs. They later called those months 'The Dead Summer'. It was during this time that Mitch was thrown out of the band. It was particularly tough for Alex who had left school and was living away from home with his girlfriend Charlene.

Ray kept on trying to convince Rush to play more cover versions. His booking business was expanding through the success of his other acts, and for a long time Rush were the most unpopular band on his roster. He'd get club owners to take Rush as a favour for having given them a more popular act.

Ray's biggest success at the time was one of the first rock bands to cover just one group's material, Liverpool, who specialised in Beatles' songs. Ray managed to set up contacts throughout Canada and in parts of the United States because of their success and was later contacted about using the group for the original production of Beatlemania, but the band members refused to wear costumes and cut their hair to look like The Beatles.

Rush used their spare time to develop their music and identity as a band. They continued practising and writing new material. It was about this time that they wrote 'Working Man'. Perhaps the song reflected the jobs the guys had to take to keep going. The sound of the group still echoed Led Zeppelin, but the distinctive interplay between Alex's guitar and Geddy's bass, still a band trademark, now began to emerge. One song, 'Slaughterhouse', even had a slight political tone. "It was a hard rocker," says John, "about what was happening to the environment and the animal world. Whale and seal hunts and that sort of thing."

Things picked up in the autumn and by the end of 1971 the band were regulars at the Abbey Road pub, a bar located on Queen Street in downtown Toronto. They could pull in as much as $1000 a week for six evenings of five-sets-a-night gigs. Most of the income went straight into new equipment.

As 1972 got under way they found themselves getting work in a whole series of southern Ontario bars, places like Larry's Hideaway, The Piccadilly Tube and The Colonial. They were performing many songs that later made it on to the first album, including 'Working Man' and 'In The Mood' (still an encore song).

A two-man road crew carted the equipment around in that staple of aspiring rock bands, an Econoline Van. They had amassed a fair amount of gear. Geddy was playing a Fender bass with two Sunn twin 15-inch cabinets, Alex used two Marshall four-by-twelve cabinets, with a 50-watt head and a makeshift pedal board incorporating a phaser, echoplex and crybaby wah-wah. John would bash away on his blue Gretsch drum kit: two bass drums, two tom toms, two floor toms and a snare.

Ian Grandy, the main crew member for Rush, mixed sound and set up the drums and lights for the band. He saw them start to build a loyal following of older fans and later recalled that some even started to request individual songs like 'Fancy Dancer' and 'Garden Road', both bar-room favourites never released on record. As their club gigs gave them more money Alex expanded his musical horizons by studying classical guitar for about six months with his friend Eliot Goldner. The lessons were cut short when Eliot cracked up his motorcycle and landed in hospital.

During the early 70's rock music began to fragment. Trends that had somehow seemed to be part of post-Beatles rock began to be separated into soft rock, exemplified by singer/songwriters Carole King and James Taylor and harder types of music - heavy metal - as played by Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath.

Other bands took a more experimental route, incorporating elements of free jazz, classical and folk music into something that was called art rock. Pink Floyd, Emerson, Lake & Palmer, Yes, Genesis, King Crimson and Gentle Giant all mined this musical terrain. While heavy metal was still the main source of inspiration for Rush, Alex's classical guitar lessons and Geddy's interest in some of the pioneering art rock bands, signalled the direction the group would take in the future.

Alex, Geddy and John often made amateur recordings in each other's basements and at various shows, and in 1972 they were able to record in a primitive studio at Rochdale College. According to Alex it was, "More like a place to buy drugs than a school. "

Bill Bryans produced in the tiny two-track garage facility called Sound Horn. "It sort of made you feel like it was the real thing," says John, "even though it was a small rinky-dink studio ... it was a good feeling that we were getting to the point where we could actually put something down."

Unfortunately the tapes were later lost.

End of Chapter 1 - Buy Used Here

Special thanks to B-man for sharing the first chapter with us.

Chapter 2

By the time 1973 rolled around Rush had five years' experience of playing in bars, high schools and drop-in centres, and managed to win over audiences in each of these performing situations. Ray and his newly acquired partner, Vic Wilson, knew that for the band to continue gaining momentum they would have to record professionally.

However, they were not having much success interesting record companies, and studio time and producers cost money, a commodity neither Rush nor their management had a great deal of. Ray and Vic knew that the only way the band could afford to record would be with an unknown producer in a small studio, overnight when studio time was cheap. Ray thought if he could get the Rush sound down on tape he would have a good chance of landing a contract with a major Canadian label.

Their first professional recording was done at Eastern Sound Studios in Toronto with David Stock producing.

The plan was to come up with a strong single. Taking the advice of record company A&R men, they recorded their first, and to this day only, cover version, a hard rock rendition of the old Buddy Holly classic 'Not Fade Away'. The B-side was a Lee/Rutsey composition entitled 'You Can't Fight It'. 'Not Fade Away' didn't have the edge of many other Rush songs of the period, although it does feature an amusing chipmunk-on-speed vocal performance from Geddy. The B-side showed more of the band as it sounded at the time and through the first album.

Once the single was completed, Ray took it around to just about every record company in Canada. But nobody would listen to it. In the early 70's few Canadian artists got record deals and those that did generally had a softer sound. Labels were looking for artists like Gordon Lightfoot, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young and Anne Murray. A heavy metal trio was about the farthest thing from these artists that could be imagined. The best offer Ray received was from London Records who told him they wouldn't sign the band but that if he formed his own label they would distribute the single. So for the cost of $400 and getting a record company logo made up and registering the company, Rush became a band with a single to their credit.

The disc, featuring a Moon Records label, sold a few copies in Toronto, but received no airplay. Ray and Vic thought the single would pave the way for a major record deal. They were wrong.

To make matters worse, during the summer of that year John was forced to leave the band through illness. He was also starting to question whether a career in rock music was right for him. Alex and Geddy continued playing with a pick-up drummer, but when John began feeling better they asked him to rejoin. He agreed.

With the single bombing and no record company willing to bankroll any recordings, the band hit a roadblock. Rush were doing well in the clubs around Ontario, yet they were strictly local heroes. Ray and Vic decided they would have to take a big risk. They would put up the cash to record an album and then go out and try to sell it. If the worst came to the worst they would then press it themselves and see if London Records would distribute it as they had done with the single. With the prospect of recording an entire album in front of them, Alex, Geddy and John began to think of ways to improve the songs.

John thought that the lyrics particularly were lacking. "I was going through a real struggle at this time with the band," recalls John. "I said to myself, 'I feel like quitting.' I was just a mixed-up kid and I began writing all sorts of additional lyrics for the songs, because most of the lyrics we had at the time were just whatever rhymed, whatever fitted in, 'cause we never really spent much time at all on the lyrics. So then finally we said, 'We've got to get some decent lyrics. This is silly, just saying whatever pops into your head and then trying to remember it the next night.' So we made a conscious effort and I started writing some lyrics.

"I was really having a hard time with myself and what I wanted to do with the band. I was very mixed up, I'd written a lot of lyrics and then I tore them up and never presented them. So when we went in and did the album all the old lyrics were sung. It's funny, because to this day I still can't remember why I did that. All I can attribute that to was that, at the time, I was just very confused about what I wanted to do. I really regret it because it was an incredibly selfish. stupid thing to do. But when you are young, unfortunately you do things like that. My mood would change from day to day, I had spent a lot of time on them and some of them were decent. Anyway, that's what happened."

Meanwhile, Ray and Vic calculated that the only way Rush could afford to record would be for the band to use the cheapest studio time available, down time, in the middle of the night. So the album would be laid down late in the evening after the group finished playing club dates. Shows of up to five sets which could stretch out to one or two in the moming. The band knew that they had no other choice.

Liam Birt who helped move the band's equipment and would later become Rush's stage manager, witnessed the sessions.

"Most of it was playing in a bar from nine at night until one in the morning, packing up the gear into a van, driving it to the studio where we'd work until the wee hours of the morning. Then pack it up again, go home, get a few hours' sleep, and just keep repeating the process. It was a crazy schedule."

Geddy remembered it as a really hectic period, but since everyone was so excited about being in the studio, they were able to summon up the enthusiasm to continue. On occasions they would go in because they just had enough time to record a guitar part or a vocal. Since John never delivered the lyrics, Geddy had to sit down and write the words he had been making up off the top of his head. When the record was finished everyone gathered round to listen. They were not happy with the results.

"David Stock did a lot of commercial work, a lot of jingles and he really took the edge off the music. We realised we had to get somebody to punch it up," says John.

So Ray and Vic rounded up more money and called Terry Brown. Brown, or Broon, as he is known to his friends and co-workers, owned a competing recording facility, Toronto Sound. An English expatriate, he had worked on recordings by Bill Cosby, Procol Harum, Thundenmug and Everyday People, but had never even heard of Rush until Ray called him up.

Ray, hardly a greybeard himself, explained that he had some kids in the studio who needed help. A meeting was arranged. When Terry got together with the band they hit it off right away and arrangements were made to work on the tapes the following week. Money was so tight that only two days were scheduled to straighten out the album. Two songs were re-recorded, 'Here Again' and 'Need Some Love'. 'Finding My Way' was added in place of the band's failed bid at a commercial single, 'Not Fade Away'. Four other tunes were remixed. The total cost for the sessions was $9000.

The band were impressed with the results of the two extra days of hard work. Ray, with new tapes in hand, began knocking on record company doors once again, this time confident that a company would sign a band with an album already recorded. There was also the added factor of Bachman Turner Overdrive's popularity in the United States and Canada, but despite the success of this Canadian hard rock band, Ray found record companies were not interested in signing another. So Ray was forced to approach London Records about distributing another Moon Records release. This time though, it would not be a single, but an album to be titled simply Rush.

The record kicks off with 'Finding My Way'. A prime example of early seventies hard rock, with prototype Rush guitar and bass attack, it features another highlight in Geddy's screeching, 'Sang some sad songs.'

Next come 'Need Some Love' and 'Take A Friend'. Neither ages well, but whatever the limitations, 'Here Again' which closes the first side, shows the band trying to stretch out a bit. A slower tempo, and an effort to bring the dynamics of the song up, down, and then up again, works. It is a sign of things to come.

Side two opens with 'What You're Doing', a strong all-out rocker. The lyrics sound as if they were written in 15 minutes, but that's part of the fun. It's followed by what became the trio's second Canadian single, 'In The Mood'. When performed as part of the band's encore, it still gets the crowd to its feet. The great hook was a little too rough to become a hit, but with a line like 'Hey baby it's a quarter to eight and I feel I'm in the mood,' how could you go wrong?

'Before And After' is the key song on the album to understanding where Rush would go next. What sounds like an acoustic guitar dominates a long instrumental introduction, before Geddy and Alex have some fine moments playing together. That and the extended introduction show a different side of the band, even if the song is a great Led Zeppelin rip-off.

Finally, the album explores territory to which Rush never really returned, with the only song the band ever recorded which deals with blue collar workers, a subject which dominates the work of Bruce Springsteen and Bob Seger. When Rush returned to contemporary characters many years later, they wrote about the suburban kids they once were. But no matter what you do for a living, 'Working Man' is a great song to play loud after a bad day at work. It was always popular with audiences and stayed in the live set for many years.

The first album stacks up pretty well for a debut. There are only two duds on the record and even these songs had some merit at the time they were put on tape. The disc still works because it is obvious that it was exciting for Alex, Geddy and John to be making a long-playing record. It has the raw, youthful energy of most good first albums, there are some great guitar solos. and Geddy sings with piercing youthful passion. Control would come but at that time it was good enough to kick out the jams.

Some of their earliest fans still swear by the record and say Rush were never able to muster up the same amount of energy again. But it does have major faults: no developed signature sound, Geddy sounds like Robert Plant, and Alex plays like Jimmy Page. The pair would have to sound like themselves if they were to have a long and successful career.

London Records agreed to distribute the album, and Ray and Vic decided to take another risk. Instead of pressing the minimum amount of copies (1,000) they shelled out money for 3,500 discs, a demonstration of faith that the band would remember for years. With their limited means, the pair were betting on Rush in a major way, but the shoestring budget still showed. There was almost nothing left over to pay for the design of the album cover, so the Rush logo was placed on top of what looked like an explosion. In Canada, the colour of the logo was red.

Before the album hit the stores, the band went on a short jaunt that could be called 'Rush Times Three'. The Ontario area performances featured a triple bill of Rush, Mahogany Rush and Bullrush.

Ray and Vic also booked a co-headlining show featuring the band and the proto-punk/glam rock New York Dolls. Rush went over well with a wasted audience at the October 27 gigs at Toronto's Victory Burlesque Theatre. They literally blew the Dolls off the stage. It was a major confidence builder. For the first time they realised they could hold their own, and then some, playing side-by-side with a name act. The hall held 1,200 people for each show and it was a bittersweet victory for Geddy who felt that playing such a large hall was nerve-racking. He would have to get used to it.

The album was supposed to be released in December, two months after the Victory gig but OPEC intervened. When the oil cartel created the first energy crisis, it also had a side effect on the recording industry since vinyl is a petroleum byproduct. The shortage of oil meant a shortage of vinyl, which in turn meant a delay in the album release date. Eventually it came out in January 1974.

Local radio began to pick up on the record. One local DJ said he decided to play it because he was always seeing ads in the newspaper for Rush shows at local bars. To the band it was something else. Geddy said he will never forget hearing himself on the radio for the first time. "It really freaked me out when DJ David Marsden played 'Finding My Way' on CHUM-FM."

Marsden got an unusual phone call that day. "My request lines were ringing and I believe in talking to the people, so I picked up the phone with Rush playing and the voice said, 'David, how are you doing? It's Alex calling.' My reply, 'Okay Alex, what do you want to hear?' and Alex said, 'No, I just wanted to thank you for playing our record. It's the very first time I've heard it on the radio.'"

CHUM-FM continued to play the disc. It also got air time in Montreal, but that was about it for radio. Still, to Alex, Geddy and John, just having a record released was a thrill.

"At the time we were one of the few Toronto bands to have an album out," says Geddy. "It was a big step for us. We moved up the ladder a few notches. Our shows began to contain almost all original material. We played bigger halls and clubs, and sales were respectable in Toronto. It (the album) still has some sort of appeal in a raw sense."

Bolstered by the release of the album and the results of the gig with The New York Dolls, Ray and Vic began going after bigger shows. But it wasn't until a month after the Canadian release of 'Rush' that the group's future would open wide.

The road to success for Canadian bands in the early seventies was either to build up a loyal audience in the Great White North, and thereby attract attention in the States, or to move to the US and be marketed as an American act. Ray had other ideas.

"Canadian managers would send their acts 1,400 miles to Winnipeg," says Ray "not even considering that New York City was only 500 miles away. My theory was the reverse, why go 1,400 miles to Winnipeg when you could play in Cleveland or Detroit which were just a few hours drive from Toronto."

The first gig Ray was able to get in the States for the band was a non-event pop festival in East Lansing, Michigan during the early spring. This outdoor festival was not Woodstock. Only 1,300 people showed up on a rainy day at the concert site... a drive-in movie theatre. The audience was not familiar with the band's material and they received an indifferent reception.

With their first battle for recognition in the States a draw at best, Danniels was eager for another engagement. A favour from a friend and a pair of receptive ears would give him a triumph.

Donna Halper was Programme Director at WMMS in Cleveland, Ohio. She often listened to Canadian music and was always looking for a new sound to give her station the edge in the rating wars.

"Bob Roper, who was an A&M of Canada representative sent me this record by a group that I had never heard of. It wasn't an A&M record, so this aroused my curiosity. I picked it up, and it had a really ugly cover, and without knowing a thing about the band, I dropped the needle down on the longest cut ('Working Man') and I knew immediately that it was a Cleveland record."

Cleveland, a working class city has always been a stronghold for hard rock bands. Halper told one of her DJs to play the song that night on his show to see how it went over.

Denny Sanders found that 'Working Man' stirred quite a reaction from the blue collar audience. Many of the callers thought the song was from a new Led Zeppelin album. "They were asking about where they could get the record, and of course they couldn't - there was only one copy," Halper says. Halper phoned Ray and Vic the next day. They worked out an arrangement to have a box of Rush records sent south to Cleveland. The albums were placed in a local 'Record Revolution' store. The box sold out in a few days and it became a big deal to own a copy of the album. Ray and Vic immediately went to Jem record importers to keep the Cleveland area supplied with Rush albums. The first few shipments sold out. But this wasn't enough for the pair: Rush were selling in the United States, and they wanted another show.

"It was very important for me to get the band there," said Ray. "I felt they could do well live. So I pulled a few strings and got a date opening for ZZ Top at a 3,000 seat theatre."

The show was scheduled for June 23. Also on the bill was an obscure Hungarian band, Locomotive G-T. Halper was there to greet Rush.

"They were all nervous when they came down," she says. "They had been playing in small places and all of a sudden they were about to play to a few thousand people. For the show I stood at the back of the hall, and Vic Wilson came up and said, 'Believe me Donna, we won't let you down.' And they didn't. They put on a really good show. Even then they had the beginnings of real professionalism. It was obvious to see. It was also nice to see people in the audience knew their songs. I can't lie and say everyone was immediately won over by Rush, they weren't, but even then there was an actual hard core. Fans would shout out song titles."

Alex remembered the band getting an even better reception than Halper did. If his memory is a little rosy, it's understandable.

"I remember flying down and being all excited about it. The show went off great. We'd been getting a lot of airplay down there and we were extremely nervous. We heard we were doing well, but we had absolutely nothing to gauge it against. We opened with 'Finding My Way' and the crowd went crazy. They obviously knew the material. We got an encore, and before we could go back up for a second encore, somebody ordered the lights turned up."

The radio airplay and word of mouth about the Cleveland show began to stir interest among US record companies. Rush were close to signing a deal with Casablanca Records. By this time the debut album had sold about 5,000 copies. 3000 were bought in Canada, the rest were sold in the States.

US booking agency American Talent International began talking to Ray and Vic about scheduling live shows. The pair also got Ira Blacker of A.T.I. to help them negotiate a record deal. After Blacker left A.T.I. he became Rush's American co-manager, a relationship that ended in a dispute eventually settled out of court, which cost Rush $250,000.

Cliff Burnstein worked in the national album promotion department at Mercury Records. "It was a Tuesday morning just like any other," says Cliff. "When Robin McBride's (head of A&R and responsible for signing acts) secretary came into my office and said, 'I've got this record for you to listen to by a Canadian band called... Rush.' I said, 'You mean Mahogany Rush, don't you?' she said, 'No, just Rush. Robin said it was important that you listen to it'."

Accompanying the album was a letter from Ira Blacker. Burnstein put on the record and began listening. 'I was immediately blown away with Finding My Way'. The letter from Blacker stated that WMMS in Cleveland was playing the album. So I called up Donna Halper, having heard side one. Donna said, 'We are playing the record and it's getting a great response 'Working Man' is the song.' I told her I hadn't heard it yet... she said, 'Wait until you hear it.' I hung up the phone, put it on and sure enough it was a motherfucker."

Burnstein knew the band should be signed. With word spreading about the trio, he did not want Mercury to lose Rush. So that very day the deal went down. Burnstein, Mercury President Irwin Steinberg and Blacker negotiated their terms via a telephone conference call. The advance was $50,000 plus $25,000 towards future recording costs.

A.T.I. and Mercury then arranged for a five-month tour that would begin on August 14. The record was set to be rush-released so it would hit the stores exactly two weeks before the tour, a mere three weeks from the signing date of the contract. There was just a few cosmetic differences from the original Moon Records' release. Basically, the label name, several acknowledgements and the colour of the band's logo on the front cover were changed. The Moon cover was red but it must have hurt someone at Mercury's head, and was changed to pink. An ugly cover gets uglier.

Chapter 3

With an album out and a tour booked, it might be said that the band had hit the big time. However, they now had months of touring, mainly as the second or third billed act in front of them. This was something John did not want to do. He was unhappy being in a rock band, and there were also arguments about what kind of music they would play. John announced he was leaving Rush again. This time the split would be permanent. With his diabetes a strong argument against touring, the musical and personal differences closed the case.

"I was into a sound very much like that of Bad Company," says John. "At the time, Alex and Geddy envisioned the band going into other areas. I also just wasn't enjoying it any more, and that's just the first tell-tale sign. I wasn't looking forward to it. I could tell I was straining the friendship with the other guys. It's just a hard thing to explain. I've never been able to pin it down accurately myself. I would sort of drift off and spend more time just talking with the roadies. I knew I had to do something. If you can't go out there and enjoy yourself you know it's time to get out."

Alex talked about the musical differences and some of the personal problems involved. "He was into the basic rock thing, and Gedd and I wanted to get a little more progressive. Our relationship was also not the same as it had been. He and I were friends since the age of eight, playing street hockey, but at this point the musical differences were happening and we didn't hang out as much as we used to, outside of working, whereas Geddy and I would hang out together all the time. So it really was a combination of his illness, our musical differences combined with the way we were growing as three people together."

With their debut US tour little more than two weeks away, the band began looking for a new drummer. A mutual friend set up an audition with the drummer of a St. Catherines area band called Hush whose name was Neil Peart. His group played the Southern Ontario bar circuit, where Neil's wild style of playing came in handy when he took on the task of playing Keith Moon licks on his Rogers kit. Most of 'Quadrophenia' was covered by Hush. Neil started out playing piano but his interest in pounding out 'Chopsticks' soon took on a more literal form. When he was 18 he went on a musical odyssey that took him far from home.

He later told Modern Drummer magazine: "I went to England with musical motivations and goals. But when you go out into the big world, as any adult knows, you're in for a lot of disillusionment. So while I was there I did a lot of other things (besides playing music) to get bread in my mouth."

He ended up working on Carnaby Street hawking trinkets to tourists at a store called Gear. He also told Modern Drummer: "When I came back from there, I was disillusioned basically about the music 'business'. I decided I would be a semi-pro musician for my own entertainment, would play music that I liked to play, and wouldn't count on it to make my living. I did other jobs and worked at other things, so I wouldn't have to compromise what I have to do as a drummer."

He had one consolation while he was in England. He found a copy of Ayn Rand's book The Fountainhead on the London tube. He found Rand's tales of fierce individualistic characters struggling to maintain their integrity inspiring. It must have seemed at the time that he had his shot at the big time and failed. He would get a second chance.

Before they heard Neil, Alex and Geddy had already listened to several other drummers. None of them had really impressed. Neil cut a strange figure coming in an old car with his drums packed into garbage cans.

"Neil came down the second day of auditions," says Alex, "and he looked really weird. He had really short hair with shorts on. He was working in a parts department, selling tractor parts. So this weird looking guy comes down with this small kit of Rogers drums, and he played them like a maniac! He was really an intense drummer! I had reservations, however, I wasn't really sure. Neil was the second or third guy we tried, so who knows. Maybe there's going to be three or four others as good. It was a bit weird. We sat down and talked a lot. Geddy and Neil talked mostly. I had these reservations. I wasn't sure. "

While Alex stood on the sidelines, Geddy was immediately won over. "After I heard Neil play, there was no one else who could come after the guy. I was convinced that he was the drummer for the band."

Neil was convinced that the audition was a disaster. "It was funny because Geddy and I hit it off right away. Conversationally we had a lot in common in terms of books and music... so many bands that we both liked. Alex, for some reason, was in a bad mood that day. So we didn't have much to say to each other. Playing together, we did what eventually became 'Anthem'. We jammed around with some of these rhythmic ideas. I thought 'Oh this is awful'."

After Neil left, Geddy tried to convince Alex that the strange looking guy was the man for the job. The argument was settled when the next drummer came in and politely played to charts he had written for all of the songs on the first Rush album.

Neil officially joined Rush on Geddy's 21st birthday, July 29, 1974. On the 30th they went out to buy equipment for the tour. "We got this big advance from the record company," says Neil. "We went down to the music store with all of us sitting in the front of the truck with Ian. Just going wild. We ran into Long and McQuade Music at 459 Bloor Street and Geddy got his first Rickenbacker (the black one). I went downstairs and picked out my Silver Slingerlands. Alex got new Marshall Amps and a Gibson Les Paul Deluxe. It was a Babes In Toyland kind of day, total fantasy. All the way home we were screaming and yelling up the highway. It was fantastic...'

With all the new equipment, the band went to work. They had less than two weeks before they had to start off for their first date. The one advantage they had was that since they were the opening act, the set would be short, 26 minutes to be exact.

Their first full U.S. tour began on August 14 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, warming up the stage for Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann before 11,642 people at the civic Arena. The fear factor was very high. Neil's first performance with the band thus took place in front of more than 10,000 people. After seeing the crowd enter the hall Geddy had a ceremonial shot of Southern Comfort because he believed that's what 'Rock Stars' did to warm up. He was wrong.

Neil: "It was both testy and fabulous at the same time. It was the big time, and a very big gig at that."

The brief set included 'Finding My Way', 'Working Man', and 'In The Mood'. The Professor--as Neil was christened--also did a short solo, a major element of the band's live show to this day.

This concert of firsts also introduced road manager Howard Ungerleider to the scene. Howard worked for A.T.I. and he was along to shepherd the lads through their first major tour. Also accompanying the band were Ian as drum roadie and sound man, Liam, who lifted Geddy's equipment and called lights, and Dave Scace who worked as guitar roadie for a few weeks, soon to be replaced by J.J. Johnson.

Howard took over the lighting after a couple of shows. Liam never had enough time to look after them properly, and Howard was glad to take the job off his hands. One of the reasons for the change was all the new equipment. "The first show we did with Uriah Heep was with almost entirely new gear," Liam says. "There was no chance to work any of the bugs out at all. So the first few weeks were frantic. It was a matter of ploughing through and persevering as well as we could, and we pulled it off."

Alex, Geddy and Neil travelled by car with Howard. Ian, Liam and J.J. used a 12-foot G.M.C. box truck to cart around the equipment and themselves. Within a few weeks, Neil began to feel like a member of the band, instead of just a last-minute replacement. His drumming skills added to the band's sound. He was soon able to give them a tightness they never had with John. "The songs were the same, but with Neil they had a different treatment," says Alex. "A really good feeling was established between us."

Once the equipment problems were sorted out, the band and crew found they had plenty of free time on their hands. Since they were an opening act, they rarely played for more than half an hour, and there was not that much set-up time, since the headliner brought the lights and sound system. Often Rush had no time for a sound check if the main act decided it needed to tune up. It was very different from playing five or six hours a night in Toronto bars.

While the crew used the extra time to see the US, the band spent hours writing new material. According to Alex much of the work was done "sitting in hotel rooms, writing heavy metal tunes on acoustic guitars."

The long hours of travelling between gigs may have been hard on a more experienced group, but for the members of Rush, their first major tour was a dream come true. "It was so exciting," says Alex. "You couldn't wait for the next day to start. Travelling... going where I never thought I would go. We all felt like that. It was a little rough on the back, travelling by car, but we could deal with it."

On one of those rent-a-car runs, 'Making Memories' was written with Alex in the front seat strumming on a guitar. The song captures the time. 'There's a time for feeling as good as we can/ The time is now and there's no stopping us.'

But no matter how enjoyable the tour was, there were at least some memories in the making that did not seem funny at the time. The band had just played St. Louis. Howard pointed the car, which was engulfed in pot smoke, in what he thought was the direction of Cleveland. Three hours into the trip as they neared Memphis, Tennessee, Howard realised he was going in the opposite direction and it was no time to stop by and meet Elvis. Alex, Geddy's and Neil's singing turned into screaming. In response, Howard turned the car around and tore off to Evansville, Indiana where the band could catch a plane. They pulled into the airport parking lot just in time to see the Delta jet 'fly by night' departing.

Rush opened for many bands during the tour. Besides Uriah Heep they warmed up the crowd for Rory Gallagher, Hawkwind, Blue Oyster Cult, Nazareth, Kiss, P.F.M., Billy Preston, Wet Willie, The Marshall Tucker Band and Manfred Mann. Gallagher always treated the band well, and in later years Rory would open many a show for them.

Rush also played a handful of headlining gigs in small clubs. At these dates the trio would play most of the first album and several early songs from their bar band days like, 'Fancy Dancer' and 'Garden Road' along with a few cover songs done a la Rush.

In September the band recorded a Toronto concert that was aired on The King Biscuit Flower Hour. On October 9, 1974, the trio taped a Don Kirshner's Rock Concert. Neil broke a bass drum head during the shooting of 'Best I Can' on ABC Television's In Concert series. That was aired on December 6, 1974. The band also appeared on quite a few local television shows during the period.

Just before Christmas Cliff Burnstein set up an important radio concert for the group in New York City. Rush's gear was set up in Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland Studios. The show was broadcast live over WQIV to Big Apple rock fans.

Cliff hoped that the concert would help break the band in New York. They had received very little airplay in the States' largest city, but if the band could get a following in the media capital of the country, success in the smaller towns would be easier to achieve. For, despite heavy touring and that initial burst of airplay in Cleveland, radio was a shaky proposition for Rush. The strategy, according to Ray was "If you were not a hit singles act, you had to tour. So that's where we started and as a result of where we played we'd end up at least getting token airplay. Record sales would go with it. We just built up territory by territory. Rush almost never received airplay before they played in a town."

Besides giving the group radio time in New York, the show gives a good sound picture of the band, just a few months after Neil joined and before they hit the studio for the second album. The guys played much of the first album, along with Larry Williams' '50s rock song (covered by The Beatles) 'Bad Boy'. Several tunes from 'Fly By Night' made an early appearance. 'Anthem' sounds much as it did on the record, but the title track is very different. Part of 'By-Tor And The Snowdog' is tacked on to the end of 'Fly By Night'.

Even at this early date you can hear the power of Peart's drumming. Geddy's singing is loose. He hasn't learned all the lines to the new songs, and he does not have the control over his voice he was later to attain. Alex sings back-up on 'Best I Can'. His guitar work is sharp. As an ensemble the group's playing is a little rough around the edges. Still, there is a powerful passion to their performance.

With much of what would become the second album already written, it was time to head back to the recording studio. Neil had taken over most of the lyric writing. Neither Geddy nor Alex really took to lyric writing, so when Neil began writing, the pair encouraged him. "Gedd and I weren't into it," says Alex. "On the first album Gedd wrote most of the lyrics, all but one song ('Here Again'). With 'Fly By Night' we figured if Neil wanted to do it, fine. Especially since when you're writing music it's difficult for a drummer to take a strong hand in the melodic writing of a song. So Gedd and I did that and Neil took over the lyrics. '

The first Rush song with lyrics penned by Peart was 'Fly By Night'. He had worked on a few songs before he joined the band, but he became the lyric writer for Rush by default. "Basically it was because nobody else wanted to do it," says Neil. "And I thought, well, I've always been interested in words. I've always loved to read. So why not give it a try. I wrote a couple of songs and showed them to Alex and Geddy. They liked them. So I continued. It later became an obsession."

The material for 'Fly By Night' was formulated during the period Alex, Geddy and Neil were really becoming acquainted with each other. A chemistry was starting to develop between the three that had not existed when John left the band. "We were pooling our creative resources," Neil later wrote, "and exploring each other's aptitudes and personalities. A real unity of purpose was beginning to develop."

In many ways it was a different band assembled in Toronto for Fly By Night. Neil's effect on Alex and Geddy and their effect on him would cause a burst in their collective creativity.

Terry Brown was once again behind the board. For Terry, the second album, recorded and mixed in 10 days, was "A bit of a panic... but we made it. In those days it was strange because you had nothing really to judge it by. All we knew were the tunes and the direction we wanted. So it was just a question of working ridiculous hours. I mean you just start with day one and make it to day two, and so on. There was no discussion of 'Is it okay', 'Do we need to remix anything', or 'Would you have rather done this or that'. When it was done, that was it. There was no time for discussion when the album was finished. We rushed out, cut it and pressed it."

No matter what the time constraints, just the fact that they were getting a chance to record a second album signalled to the band that they had staying power. As it turned out, a lot more than they could have ever imagined.

Hectic understates the last minute nature of the way the record was completed. Alex said, "It was 8 o'clock in the morning, and we had just finished mixing when Vic Wilson came down to pick up the tapes. We had worked most of the previous day and night and then on the final night straight through until the morning. After all this we went to the airport to catch a 10:30 a.m. flight to Winnipeg for a gig. We were so tired we barely made it to the airport. I remember sleeping for an hour and a half on the plane, getting there, waking up, and it was freezing cold. We had a horrible day. It was snowing and it felt like minus 530 degrees. I'll never forget trying to get it together in the dressing room before the show. A crazy day."

The hard work resulted in a large step forward for the band. Putting aside for a moment the songs themselves, the playing sounded as if the revamped trio had been together for years, not months. Neil was already showing that he was a great rock drummer but the improvements were across the board. Before, the distortion had covered up the fact that only three people were playing, now it was the group's chops that did the trick. All three shared leads and rhythms. Geddy and Alex's trademark bass and guitar riffs are in full evidence. Even with Neil's first appearance on vinyl, he has his own style. You can hear the manic fury of a Keith Moon, but there is an added control that is strictly Neil Peart. 'Fly By Night' showed that the three musicians could sound like five or six.

The straightforward, hard rock of the first album was still there. Yet it was tighter and more focused. Quieter passages were brought to life by Geddy and Alex's playing of acoustic guitars. Neil's battery of percussion toys brought new textures to many of the songs. In comparison to 'Rush', 'Fly By Night' is almost symphonic rock.

The album opens with 'Anthem', a tough tune with tough subject matter. Neil had interested the other members of the band in the philosophy of 'objectivist' writer Ayn Rand, and the title is taken from a novella of the same name in which Rand wrote about a world where individual initiative is forbidden, and all is done collectively. To Rand, this was the ultimate horror. Having expenenced the Russian Revolution in 1917 at first hand, she believed that all of man's great achievements were accomplished by individuals and that collective actions were often destructive; in many cases destructive of society's most outstanding figures. To the band her uncompromising position was a model for many years for it seemed to mirror their determination to do things their own way. Paradoxically Rand would probably have been horrified by the group. Although they went their own way, they did so collectively, and Rand railed against long-haired hippies and rock music on several occasions, most notably in a collection of essays on the Woodstock Generation.

'Best I Can' comes next, a Geddy/Lee [sic] rock composition like 'Beneath, Between And Behind' which follows.

'By-Tor And The Snowdog' marks the beginning of a Rush tradition of extended story songs, in this case a battle between By-Tor and the Snowdog. The song has bite, in more ways than one. Howard actually came up with the title one night at a party at Ray's house. "Ray had these two dogs," says Howard. "One was a German Shepherd that had these fangs, and the other was this little tiny white nervous dog. I used to call the Shepherd By-Tor because anyone who would walk into the house would get bitten by him. Ray would go, 'This dog is trained fine, don't worry about it.' Well the night of the party we were sitting down eating our steaks when the Shepherd started biting my leg. I started screaming and calling the dog a By-Tor. Now the other dog was real neurotic, constantly barking and jumping all over you. And since he was a snow dog, I started calling the pair 'By-Tor and the Snowdog'."

The second side opens on a high note with 'Fly By Night', a really potential hit single, followed by 'Making Memories', a tune which captures Rush's early experiences on the road. Next is 'Rivendell', inspired by the ever-popular J.R.R. Tolkien, whose tales inspired a series of early '70s rockers including Led Zeppelin. 'Rivendell' is the name of a city of elves mentioned in the Lord of the Rings trilogy and other works by Tolkien, a paradise on earth. Geddy's keening vocals suggest the beauty this imaginary refuge had for him and Neil. Incidentally, Tolkien's influence could also be heard on 'By-Tor And The Snowdog' and several later songs by the band.

The album closer, 'In The End' opens quietly, much like 'Rivendell'. But then Alex kicks in with a killer guitar riff followed by Neil and Geddy before a classic Rush tempo change.

'Fly By Night' hit the record racks in February 1975. By that time the band were already back on the road, opening shows for Kiss and Aerosmith, with the occasional headlining gig on the side.

The dates with Kiss were particularly memorable. Kiss were on their way to becoming one of rock's biggest bands. Their mixture of extreme theatrics, painted faces and bone crushing hard rock made them a tough act to precede. Their fans expected a spectacle and Rush managed to hold their own. The members of Kiss were friendly to Alex, Geddy and Neil, and much fun was had on their tour.

Gene Simmons, the long-tongued bassist of Kiss, said "We've always had great bands open for us. We believe in exposing good talent to the people. We liked Rush for their Led Zeppelin junior approach. Very straightforward kick-ass rock."

Neil described the final show Rush played with Kiss to a writer from Circus magazine. The date was in San Diego. "We were going to dress up as them, put on their make-up, and go out and do our set as them, but what finally happened was an onstage piefight that happened in front of 6,000 screaming kids. They caught us at the end of our set by surprise, and the whole stage was covered in shaving cream and whipped cream. Then it was our turn at the end of their set. All their guitars and drums and machines were completely buried in shaving cream, so their encore sounded just great!" "The end of tour party," said Geddy, "was one of those great all-nighters with stuff being thrown out of the hotel windows."

In between tour dates Alex married his long-time girlfriend, Charlene, on March 12, 1975. They had been seeing each other since Alex was 15. The honeymoon was a little unconventional. "On our honeymoon," says Charlene, "he was playing up north and I had to go by myself. He had a couple of shows to do, so he came down and met me later. I thought, hmmm! This is a sign of what it is going to be like (laughter)."

Also around this time Ray wanted to change the name of Moon Records. Rush made some suggestions and eventually they came up with the title and theme of Anthem so he used it as the new name for the company. He also liked it because Anthem sounded like a great name for a record company. "It was tied in with Rush but it didn't mean we couldn't put another act on the label," says Ray.

The second tour saw the band begin to pick up pockets of loyal fans across the United States. The gigging paid off with limited airplay, mainly in the Midwest, where the band began to sell out small gigs as a headliner. While Rush were treated very well by Kiss, not every group they opened for was so kind.

On April 13, the trio played a sold-out show in front of 4,500 fans at Detroit's Michigan Palace. Another show at the Agora in Cleveland was a tour highlight for Alex. "We ended up going to cities two or three times in the space of a year. In Cleveland we did that show with ZZ Top. Then we came back and did one with Uriah Heep. We got a real strong response the second time around, so we were booked into the Agora two weeks later. It was a hot, sweaty, sold-out night. Lots of electricity."

Donna Halper was the stage announcer for the Agora show. "Rush had worked their way up from being the third act on the bill to the point where they could take an entire show themselves in Cleveland and just command the performance. Fans were fighting for tickets for days. The concert was then rebroadcast on WMMS."

While on tour with Aerosmith in Michigan the band received a phone call from a very drunk Ray Danniels. He was ranting and raving about Rush being the best new trio around. It took Alex, Geddy and Neil a few minutes before they realised what he was trying to say. Rush had won a Juno award for the most promising new group, the Canadian equivalent of the American Grammy Awards. The trio promptly went out and celebrated on their own. Rush had never won any kind of award before, so a few dozen drinks seemed to be in order.

The band closed the 'Fly By Night' tour with a short Canadian jaunt. But before they could begin the dates in their homeland there was the little matter of a rental car they had hired for the tour. They told the rental company they were only going to use it for a short period of time. Eventually it was returned a few months later with 11,000 additional miles on the clock, no hubcaps, no rear-view mirror and a broken radio. Alex later told David Fricke in an article for Rolling Stone magazine that the vehicle was ruined. And that the people at the rental agency "were quite surprised."

On June 25, Massey Hall in Toronto held 2,765 Rush fans as the band blasted their way through a sold-out show. Max Webster warmed the crowd. Alex was blown away by the way the fans seemed to know the words to every song. Neil could hardly believe he was playing at Massey Hall. He had always dreamed of playing at the venue and there he was pounding away as part of a successful rock band, and in top form too. His solo spot utilised speaker panning and a phase shifter that filtered the sound of his snare. To Geddy it was the culmination of seven years of hard work.

'Fly By Night' was out-selling the first album and was not unheard of on radio. The second half of 1975 would see a longer album, extended songs, more complex arrangements and lyrics, constant concerts and a serious testing of Alex, Geddy and Neil's commitment to make music their own way.

Chapter 4

The 'Three Men Of Willowdale' returned to Toronto Sound in July of 1975 to begin work on their third album. Terry Brown was once again producing. With the success of the first two efforts, the band were in a confident mood, and their steadily increasing popularity had heightened the trio's resolve. In Neil's words it "helped to reinforce our belief in what we were trying to accomplish, and we became dedicated to achieving success without compromising our music, for we felt that it would be worthless on any other terms."

As with 'Fly By Night' most of 'Caress Of Steel' was written on the road. The new material was a real stretch for the band and with only 12 days budgeted for the recording and mixing of the record, it would prove difficult to get the sound they wanted down on tape.

The main factor in their favour was that much of the material had been worked out beforehand. Alex remembers how the album's musical and lyrical patterns were developed. "Neil wrote the lyrics for the 'Fountain Of Lamneth'," says Alex, "and he thought it would be kind of nice to try to incorporate a very loose concept by having a starting point, and an ending point, which would cover a whole album side. It would be a complete story but broken up so that they could be taken as individual songs, that unless you looked closely wouldn't necessarily relate to each other. That was how we approached it. It was also important for us to continue the By-Tor thing on the album with a piece that was eventually titled 'The Necromancer'."

But the band had bitten off more than they could chew. The time and care needed to work on such a complex undertaking was not possible with less than two weeks in the studio. In retrospect Terry agrees with this assessment, referring to the album as an ambitious project that did not quite come off. According to Terry, the production is too loose, and a few more weeks of work would have solved many problems. But he thinks that the musical ideas were very strong. Still, the record is probably the first where Rush were conscious of developing an original sound. While they do not quite achieve their own sound, they go quite a way towards doing so. The sessions laid a firm musical base for what was to follow.

The album begins with a bang, with 'Bastille Day' one of the finest hard rock songs ever recorded. It is a song of the French Revolution with music to match angry words, reaching new levels of complexity and ambiguity. Clearly influenced by Charles Dickens' riveting description of the terror in 'A Tale Of Two Cities', Neil expresses both the savagery of the mob, and the reasons for its behaviour. While at other times in the band's career Neil's mistrust of people acting en masse would bring out a palpable loathing of such collective action, on this song you can't quite tell which side he is on. This impression is reinforced by Geddy's passionate vocal. After all, the band now had the experience of playing in front of thousands of excited people and seen both the positive and negative aspects of communal experiences.

A complete change of pace follows. 'I Think I'm Going Bald' opens with an echoed shriek from Geddy that sounds as if he has just seen what he is about to describe. It is about waking up, looking in the mirror and thinking that you are going bald. The song has an amusing closing lyrical prophecy; 'But even when I'm grey I'll still be grey my way.'

'Lakeside Park' evokes lazy summer days and nights. The kind of life that the band had given up in order to 'make it'. Geddy's vocal has a poignancy that shows that at least part of him misses those carefree days. It's the kind of song to which just about every listener can relate because most of us have a Lakeside Park of our own.

Next comes a continuation of 'By-Tor And The Snowdog' in 'The Necromancer'. The strangest introductory vocal about 'three travellers, men of Willowdale' was created by treating Neil's voice with special effects using a digital delay unit and slowing the recording speed. It expands on the tentative art rock experiments of 'Fly By Night'. A whole bevy of effects are employed to heighten the sonic experience of the piece, or actually pieces. 'The Necromancer' is really three movements strung together as one, united by the battle between By-Tor and the Necromancer. The song shares with several tunes from the previous album a heavy J.R.R. Tolkien influence with its talk of wizards, wraiths and tower fortresses. It is also the first time Rush extended a concept from one LP to another.

The second half of the album contains Rush's first side-long composition. On the cover of the record, six individual songs are listed, but even a casual listen reveals they are meant to be taken as a whole. There are several recurring musical and lyrical motifs, and the tracks all melt into each other. The epic appears to be about a man's compulsion to see and taste the world, and if possible to understand what these experiences mean. The traveller finds that the key, the end, the answer, is that there is none. The suite's highlights, a drum showcase for Neil on 'Didacts And Narpets', 'Bacchus Plateau', 'The Fountain' and 'No One At The Bridge'.

Even with the strict time limits, you can hear how the band is developing its compositional skills. The playing is solid with definite signs of improvement, but it is not as noticeable as the leaps in technique made from the first to the second album. As events turned out, 'Caress Of Steel' would come in for quite a drubbing, but the record, if far from perfect, contains much of what Rush would become, and more than that stands up today as a whole, something that only parts of 'Rush' and 'Fly By Night' achieve. As a matter of fact, just like the first record it has a small, but devoted band of fans who think it is the best thing Rush have ever done. Although critical of his own production, Terry Brown is one of those who 'loves' the record.

Rush played down the disc in later years, but Terry says that, "At the time they were very happy with it. Not many others shared this view. Right from the beginning it was not going to be a very big record (laugh), everyone who heard it sort of went 'Um, yes, oh, a new direction'. From an outsider's point of view it was very difficult to get into 'Caress' quickly. But there are some great tunes on it."

Neil talked about the attitude of the band while they were recording the album. "We went in serene and confident, and emerged with an album that we were tremendously proud of, as a major step in our development, and featuring a lot of dynamic variety and some true originality."