Prime Groover

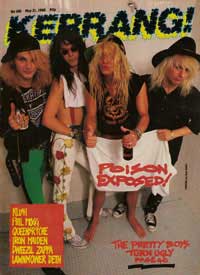

By Chris Watts, Kerrang! No. 188, May 21, 1988, transcribed by pwrwindows

Canadian trio RUSH have just completed a UK tour that was totally devoid of Metal Mayhem. What's more, drummer Neil Peart thinks rock 'n' roll should be treated just like any other job of work. CHRIS WATTS sat down to roll the dice and ask questions about the cerebral lyricist's trivial pursuit.

There are no naked girls in Neil Peart's hotel room. There are no mysterious capsules, broken television sets or recently abused serving maids. The room is spotless and Peart is dressed like any other casual Canadian in London town. Frankly, I'm a little disappointed.

I'm probably not the greatest Rush fan in this world. Sure I've heard the albums and the raving adoration of friends who know better. Oh God, they all moan Rush are just so...so...intense! Yesterday somebody even told me that in 1979 'Hemispheres' was a pretty radical album to own. I found his opinion wildly distressing.

Couple this to being warned by a tour manager that Neil Peart is wonderful, honest, down-to-earth and blah, blah, blah, but can be prone to walk out of interviews if pushed, and my day is just about complete. Who is this guy? Is he the drummer with a rock 'n' roll band or is he merely God?

As it happens he's a little of both.

At best Neil Peart feels uncomfortable with the European media. I was about to dismiss him as a spoilt rock brat waving his broken rattle, but found the truth is far more painful.

In the late '70s a British 'music' tabloid condemned Rush and Neil Peart in particular for glamorising the Nazi atrocities. When you learn that Geddy Lee's parents were both survivors of a concentration camp and that his father later died of the lasting effects, you begin to understand the resentment.

Rush are back in town with their fourteenth album, 'Hold Your Fire'. In 1968 they were paid 25 dollars for playing bad Cream covers in a northern Toronto coffee bar. In 1988 people will tell you that Rush own the world. For 20 years their name has been synonymous with thoughtful, lavish and progressive techno rock. The individual musical proficiency has become a yardstick for imitators and until 'Grace Under Pressure' left me Cold.

In 1984 Rush grew up.

"Suddenly I wanted the real world to be as exciting and bright as fantasy," Peart explains in his role as lyricist.

"The early '80s was a difficult time. A lot of my friends weren't working or were having health problems, marriage problems, and I was very moved. I wrote that album out of empathy because my life was doing pretty well.

"A lot of our early work was pure escapism and at the time it was right. We were teenagers growing up in the suburbs and we needed to escape. I really dwelled on Science Fiction and fantasy which I've now outgrown. I can smile at my naïvety but I can't sneer."

A leaner, less pompous Rush emerged with 'Grace Under Pressure'. For the first time in ages a photograph of Alex, Geddy and Neil appeared on the cover. They'd had their hair cut to celebrate the passing decade. I wouldn't say I became a fan but I still play 'Distant Early Warning' and 'Afterimage' when the mood strikes.

It's an album that, thanks to Peter Henderson's stark production, belongs in the 1980s. The original choice had been Steve Lillywhite (noted for his work with Big Country and U2) and Neil Peart agrees that the rumoured partners might well have been seminal.

'Grace Under Pressure' was followed in 1985 by 'Power Windows' and now 'Hold Your Fire'. Both the latter were recorded with Peter Collins at the helm (currently working with Little Angels). On 'HYF' as ever the sound is enormous. As ever the music is intricate and faultless. As ever it goes nowhere yet goes everywhere. I guess Neil Peart would take it as a compliment.

So how does an established rock act approach their fourteenth album?

"I'm always nervous," Peart says, "about approaching a new album with a blank slate. I'll have a few phrases, ideas just bits that I take in with me. We've never made too many plans though about what the album should accomplish. For the most part it's pretty much intuition. We generally use the last album as a launching pad. Listening to 'Power Windows' just before we started to record, my fresh reaction was that it was so dense. We wanted to strip the sound away a little bit.

"Lyrically I always go into the studio prepared for rejection. Sometimes I know in my own mind that the lyrics are wrong, and that's where Geddy is so helpful. It's a very fragile situation having to let people know that their work is perhaps not up to scratch. There's a quote from Sting who said, describing the friction in the Police, that telling someone their song was bad was like telling them their girlfriend is ugly!

"But none of us is so egotistical to imagine that something is great just because we've written it. All of us know when a song isn't going to work."

He sits hunched over as I ask my questions and frowns with thought. His eyes are piercing and restless, his brain rapid and concentrated. There is the temptation to emerge from a conversation thinking the man is some deep genius. At the end of the day he's an immensely likeable and informed talker who shuns publicity and takes his hobby of endurance cycling very seriously. He would like to be seen as nothing special.

"Yes, it does annoy me, when people glamorise the band," he says earnestly, "but also when they over trivialise it as well. I tend to see it in prosaic terms of getting up in the morning and going to work. I put in an eight hour day like anyone else. I'm at the venue in the afternoon, I soundcheck, and from that moment I do nothing but think of my work. Those two hours on stage are a part of a whole day spent concentrating on that time. It really can be condensed into that elemental reality. I would like to see it refined into much more of a work ethic than it is."

He shrugs and lights a cigarette. "Unfortunately you're battling against decades of people glamorising and trivializing it. That has been allowed to happen. For a lot of people that is the life and most bands don't take it as seriously as Rush. It is a strange situation for any normal person to be thrown into. That responsibility can be sobering."

Dangerous?

"Yes," he replies without hesitation. "Just in the terms of stress it's dangerous. I've read a lot about it and professional musicians are right up there in the Top Two with brain surgeons! Ultimately you have to pay a price for that stress but the rewards are great. Mentally, spiritually and physically it is harmful but the price you pay for the freedom to express your worth it.

"A example is Michael Jackson. Imagine if he'd grown up in the Detroit suburbs with his family and they'd all gone to work for General Motors. Do you think he'd be having an operation on his face every month? Would he be as weird as he is?

"Looking at the casualties is pretty sobering. People find it easy to dismiss all the people that have been killed by the poisons, the temptations and the unreality of their lives."

But people perpetuate the myth?

"Oh, sure," he says and searches for words. "People want their myths, their glamour. They want people to be larger than life as if it was almost a transplanted religious impulse. It goes back to people wanting something to dignify their existence, something that transcends stomach-aches and tooth-aches!

"People will not have the fact that triviality and glamour can kill people. Whoever you are, whatever you are, you've still got to get up in the morning and do your job."

In a bizarre twist then, people half expect you to play the part? In a bizarre twist, people would like Rush to die in a plane crash?

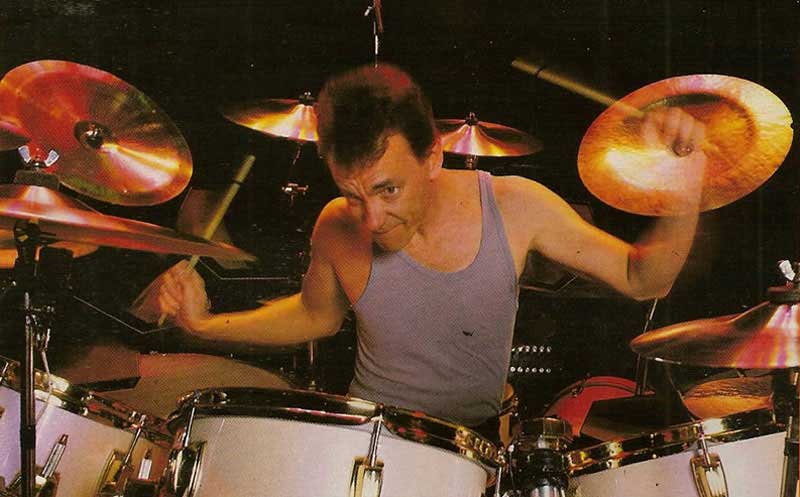

He leans back and laughs nervously. "Well, I thought about this quite a bit. How much respect did drummers like Keith Moon and John Bonham have before they died? Not much. They were drummers I admired very much but they were frowned upon by musicians of their time.

"Now everyone feels safe in lionising them. They're not going to come back and embarrass people by doing something artistically horrible. They're not a threat any more.

"What you're getting at here, apart from copy for your magazine, is true. When a band is alive and doing well they're a threat. You're also a threat to your admirers because you might sell out and do something that would embarrass them for liking you. That's happened to us all with people we've admired.

"It's like the Evangelists in America. People are giving them their money, their love, their tears, only to be betrayed when the man is found in bed with a prostitute! But people want to place that trust. I'm awestruck, totally amazed, that people can be so gullible. To be twice gullible in forgiving him is beyond comprehension."

Sometimes I fear that Neil Peart doesn't belong in rock 'n' roll. Yet Rush have proved time and again with heavy and extravagant tours that they belong in the arena.

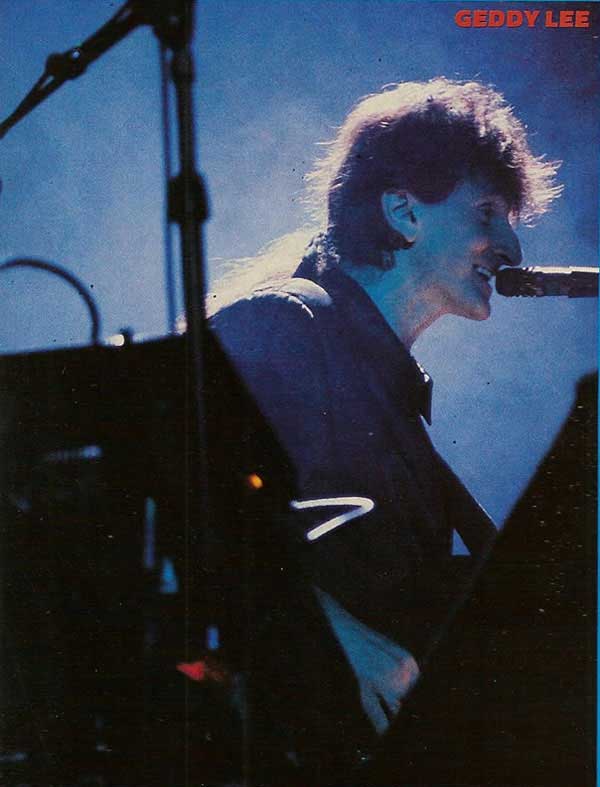

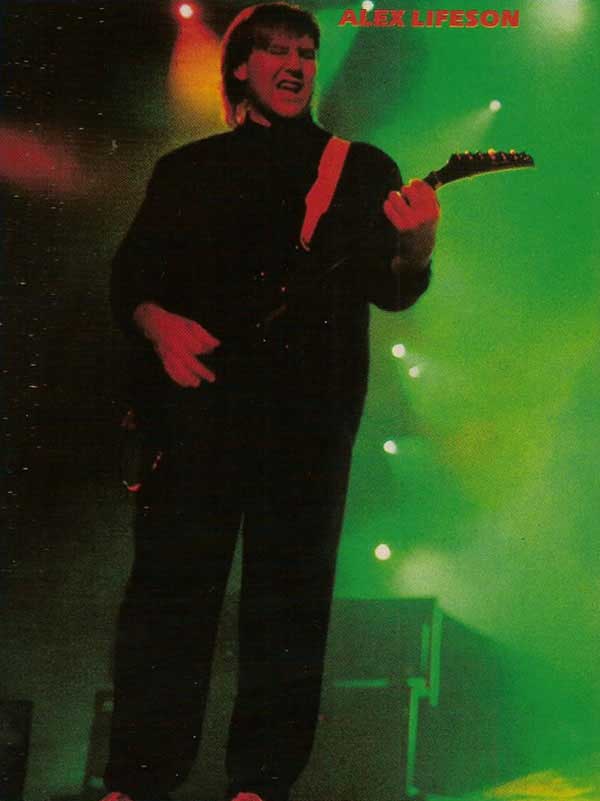

The 'Hold Your Fire' shows that have just swept the country have been no exception. Music controlled by computers, phantom keyboard players and a crystal wash of sound are my lasting impressions. Somewhere beneath the giant slide-show, 99 red balloons and sound-sensitive lights, I remember three little people.

I wondered what, for Rush's purpose, was the point of a live show?

"My fundamental responsibility," Peart says, "is to express our music. In North America we don't have Top 40 radio to let people hear it. Our music is only going to interest a small percentage of people who listen to music anyway, so touring is a way of giving new people a chance to hear us. In the broadest sense that's the purpose, but walking up the stairs to the stage is a different mentality.

"It's never so rational or reflective. At that time it's the challenge of knowing you have a blank slate on which to make an impression. It never gets any easier and it's something I never take for granted.

"Once I get complacent - bang! - I'll make a really stupid mistake. But if we do play a really good show there is a certain glow, a certain space between you and the earth that lasts for about a day.

"Our first show, or rather my first show with Rush, was in front of 10,000 people (as the support for Uriah Heep and Manfred Mann in Pittsburgh). We'd only had a matter of days to rehearse but I remember it wasn't a feeling of fear walking out to my kit. It was just an apprehension, anticipation, also exciting.

"Clich�s aside, it was truly awesome. That feeling is still with me. There is an intangible electricity about a hall full of people that starts to crackle around. The anticipation and excitement are brought in with the crowd when the gates open."

Does a stadium full of adoring people frighten you?

"It doesn't frighten me because I can't accept my superiority. Adulation presumes that superiority and I won't accept that. I don't feel comfortable with the mantle. Obviously it's nice to have respect for the work I do and that's the truth in those simple words. It doesn't allow for me to be larger than life."

He stares at the ceiling for a brief moment. "It's a double-edged sword I find intriguing. A lot of artists play down to their audience. They don't write what they want but instead write what they think their audience will accept. That again presumes a superiority and eventually that turns to cynicism.

"Rush have never seen the point in that. We've been criticised for writing over our audiences' heads but that's perverse logic. If we're capable of understanding it then our audience is as well. If we don't communicate with them then it's our fault for not being clear enough. It's not because our audience is stupid.

"If they don't want to care about the lyrics then that's fine. It's like expecting them to be able to play a paradiddle or put a three-part harmony together before they can enjoy our music. Why should they have to care?"

So why pay so much attention to lyrics?

"I guess if I had to justify my existence and say that what we do is important then nothing is important. It's entertainment. It has to be entertainment. If I'm forced to dignify it then I'd say that I have the leisure to sit back and assimilate my experiences, mysteries and relationships. I am professionally allowed to sit and think! People who get up and go to work may not have the leisure but they have the same thoughts and worries as me.

"More and more I want to grab experiences. I want to see more of the world and how people behave. I really feel that child-like sense of being such a beginner, like there's so much to see and learn. That's what really lights my fire."

Rush are the band every public schoolboy would like to emulate. They could take pride in flying in the face of fashion and deliberately create a limitless boundary in which to play.

With the possible exceptions of Pink Floyd and post-'Communique' Dire Straits, Rush stand alone. The only band who have the gall to still merge a bass solo with a revolving drum riser in 1988 are heading towards the '90s with quiet confidence.

"The '90s could bring anything or nothing," Peart says. "The '80s have changed so greatly with so many technological advances that people - myself included - tend to take them for granted.

"In the world of politics there are big bad things happening but also big good things. Even the East opening up a crack to the West is a major step towards something. In the world of communications the world has jumped. I hate rapid communications and tend to frown on telephones and faxes but the point about that stuff is that it's for real. For all of us as a band, computers have become a major part of our world.

"Yes, I'd say we're happy. The only future we've ever needed is to talk about another album and we are talking about that. So that's our future and, yes, there still is that drive.

"If the band weren't obsessive about what we do any more, then I think Rush would die. The compulsion as a drummer is still in me and my obsession with lyrics is still active, so to ask Rush when they'd cease to exist is a question that would never be asked by the band.

"Fortunately we reach a wide enough audience to ensure that our creativity can be self-perpetuating. We always take it that unless someone says otherwise we'll still be working for the next album and the next tour. That's all the future and security we've ever needed."

As I mentioned, I'm not the greatest Rush fan in this world. Even I, however, can see the point.