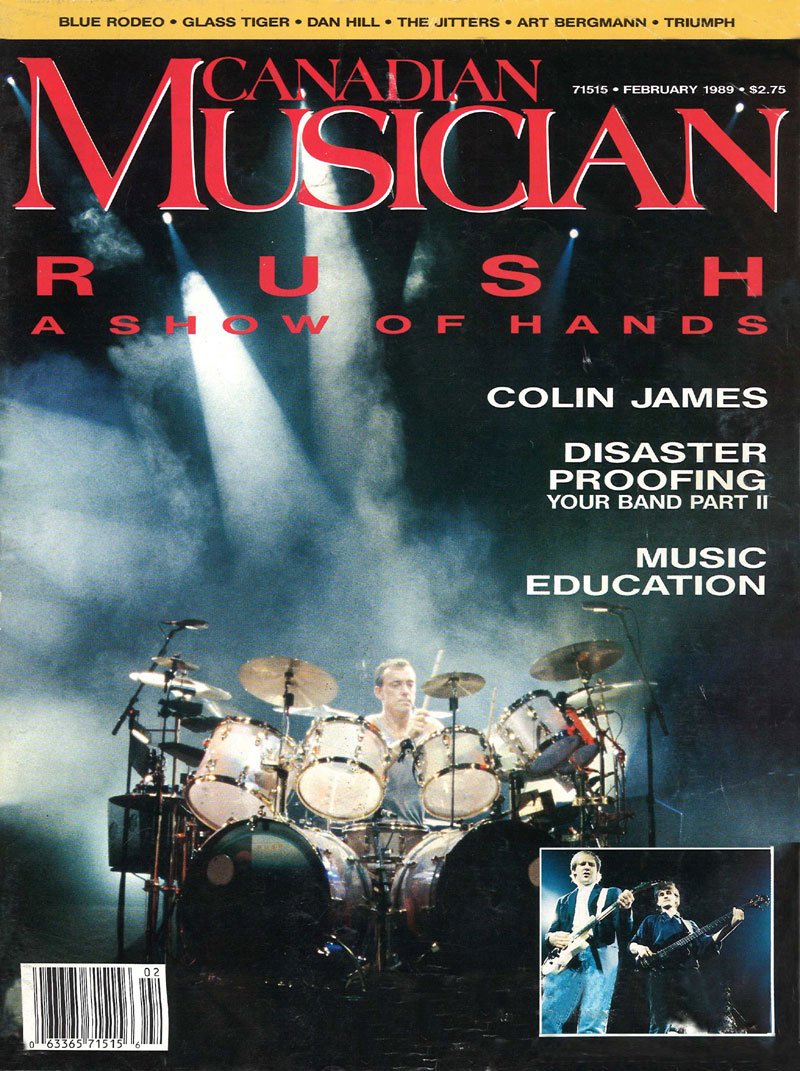

A Show Of Hands

By Bill Reynolds, Canadian Musician, February 1989

Rush is the band with the attitude, 'I've got licks and I'm gonna use 'em!' From their early days as an extreme hard rock trio to their pre-eminence at the top of the heap in the eighties, they've always delivered to their loyal fans music that will never bow to top 40 tastes. Their albums have become increasingly melodic, but they reserve their right as players to 'strut their stuff' as often as possible.

Rush's mastering of technology over the years, along with the desire to overcome the pretentious stigma of being 'composers' has resulted in a series of more sophisticated and melodic recordings, culminating with Hold Your Fire in 1987. As is their custom, every fifth LP is live, and A Show of Hands, the third such release of their career, is out this month.

Bassist, singer and reluctant keyboardist Geddy Lee, who has never spent so much continuous time at home as he has these last six months, stopped by the Anthem record offices to discuss where the band has been, the making of both the film and the record of the last two tours, and to hypothesize on the future prospects of a band that has worked hard to deserve the respect and success it has received, a band that shows absolutely no signs of flagging in the stretch.

Lee is a quiet and thoughtful kind of guy. He peruses questions carefully before providing articulate answers that usually get to the root of his, and his band's, mindset at any given point in their musical life. If it seems slightly indulgent to release a third double live album, Lee points out that it's a formula which has served to provide a spell of rejuvenation for the creative juices of the band.

"It makes sense to us because it buys time from the rigours of touring, and it's a historical update. It's appropriate every once in a while to record how your sound has changed and evolved over the years. It's also very instructional, because it can be very painful listening to live tapes. All musicians are infinitely more hypercritical of themselves than would be the general public. But eventually you get past that stage of noticing the little mistakes and start thinking about the stuff you're really proud of. It's like taking stock of your abilities as a player."

Rush completed their Hold Your Fire tour last winter, but work on the record hadn't even begun. They had 40 hours of tape to sift through, and what began in the minds of the Anthem people as a quick two-week exercise quickly ballooned to six. The live recordings were spread over the last two tours, including Power Windows in 1985. The band made the decision to tape as many shows because of their experiences with the last two, All The World's A Stage (1976) and Exit... Stage Left (1981).

Lee says of the first live recording, "It was very raw. Our sound was like that in those days anyway, and we did very little fixing up or knob twiddling. We were growing so fast that by the time it came out we thought we could have done better. As a consequence it was very difficult for us to listen to, even though it was immensely popular."

Onward to 1981: when they decided to redress the balance for Exit... Stage Left, they convinced themselves that it would be appropriate to eliminate the ambience of the crowd in favour of technical accuracy. The lack of audience involvement made it too sterile for the effect intended. Lee says, "We were trying to keep every hair in place. We were being naïve and missed the point."

With A Show Of Hands, Rush feels it has achieved the happy medium -- a live document that is technically impressive to listen to, but at the same time retains the buzz of the crowd. To achieve the vibrancy they were so badly searching for, they reasoned that if they recorded dozens of shows, they would find a few moments that transcended the uptightness of having the tape machine on. "We were trying to find those comfortable takes. We were splitting ourselves into two, playing for the tape and the audience. If you make a tiny mistake, in your mind you feel you've blown it, and you get uptight. It's a very psychological thing."

Ironically, after hours and hours of taping, the loosest gig was on the last night of the Hold Your Fire tour. They played three nights running in Birmingham, England, the second of which was being filmed for a simultaneous release. Lee explains, "We had 10 cameras around the stage, big cranes, guys all trying to be discreet, but in no way being discreet. Talk about being uptight! Worried about the recording? Forget it! You got cameras stuck in your face."

The next night the whole band was completely relaxed, because the camera crews were doing only longshots, and they couldn't even see them. The tape was running, but they were just happy to be without pots in their face. In the end they went with their instincts in choosing final versions, reasoning that any serious mistake could easily be corrected in the studio, whereas essence was a more difficult quality to come by.

SRO-Anthem V.P. Val Azzoli says the band was very concerned about paying attention to CD technology with this LP. They wanted to give fans a break because it's a live recording, so they put the double LP on a single CD, filling all but 12 seconds of the 74-minute physical restriction. He says, "everybody was freakin' out about that. 'You can't do this!' Why not? 'Well, it's never been done before.' So what? They wanted two CDs so they could charge $40 instead of $20. They were just being greedy. It was like, 'Stop already! It's a live record! Let's give 'em more for their money.' that would have been pure profit for the record company and the retailers, profit which we wouldn't have seen, but we won that battle."

With the LP mixed and ready to go, Lee figured it would be a breeze to finish the movie soundtrack, but instead he was slaving away for another four weeks getting that second night in Birmingham up to snuff. "I naïvely thought we could use the same takes from the LP, but as consistent and automatic as we sometimes are, it wouldn't work." Azzoli wants to see the concert film released in conjunction with the record to selected repertory cinemas in North America for a limited run. It will eventually find its home on the video racks, like the other films.

Rush's shows are usually 130 minutes, but the film gives a slightly condensed version at 95. While the LP draws mostly from material on the last couple of records, the film is a real concert with a definite beginning and end. Howard Ungerleider. Rush's wizard lighting director, used a few tricks, like adding a couple of white spotlights, to provide more clarity with background silhouettes. Because there is so much trouble with transferring the colour red from live to film, and especially video, special precautions had to be taken. Lee thinks Rush finally has been captured in its essence onstage. "It's a new experience for me because I've never really seen the show, but we tried very hard to get the atmosphere and wonderful moods Howard creates."

The incredibly complex procedures required to execute Rush's stage show have developed because the band heartily embraced technology many years ago. It all began innocently enough, with their desire to have Lee play rhythm guitar while guitarist Alex Lifeson performed solos. They introduced the bass pedals in the seventies to facilitate Lee playing two instruments simultaneously, and since then have never looked back. As Lee says, "It's like the little thing that grew. We became addicted to the idea of having an extra member in the band without having an extra member. Now almost every limb I have is connected to something."

Lee says at times he feels very constrained by the banks of keyboards, sequencers, sampling devices and MIDI control devices, mainly because he'll always consider himself a bassist first, a singer second, and a keyboard player a distant third. "I consider myself, if anything, a synthesizer arranger, almost a choreographer. I do a lot of writing on the keyboard, and then I use the Performer software with the MacIntosh computer. Before any other instruments are put down on tape, the keyboard arrangements, except for the subtleties, are final. But with live performances it's a whole different story."

Jim Burgess of Saved By Technology convinced Lee that the complexities of a Rush studio recording could indeed be recreated live. Offstage someone will set up the samples for the songs, but Lee triggers them himself. "It's very important for me to do that. and not someone else. It's a fine line, but I still have to be in the right place at the right time. If I hit a sequencer late, it's my fault. That way, I'm still in control, and my organization and rhythm have to be impeccable."

For Lee, the restricting aspect of being in charge of so many split-second decisions is that it takes him away from his natural role as 'the player'. He is pleased to still be able to write aggressive tunes like "Force Ten" on the bass guitar and know they couldn't possibly have been written on his keyboard. It's then that he realizes the true usefulness of the keyboard as an arranging device. "That technology is amazing because it's like having 30 extra colours to work with, but at the same time we maintain a central idea of what we want at all times. Rush is a constantly evolving concept of what a hard rock band is how many people we can pretend to be at the same time."

With the ever-present use of keyboards comes texture and the inevitable richness that accompanies it. Lee is surprised when the word mellow is used to describe Rush's music now in comparison to a few years ago, mainly because he can't see working with Lifeson, whom he describes as a ferocious guitar player, in a mellow band. But he does allow that Rush has become preoccupied with melody over the years.

He considers the first stage of Rush to be raw and energetic. "The temperament was 'I've got licks to play that I want people to hear.' It was a cocky, strut-yourstuff attitude, and my singing was extreme too because I had to cut through that. But I don't have a desire to belt it out like I used to. The older you get as a person, the more you get to know yourself, and you want to use those things. And so here we are, the same band 15 years down the road -- a rarity in itself -- and we're not opposed to letting our growth as people and the new music that's around influence us.

It's important for Lee to make sure he writes a good melody for his voice now, one which can highlight the various moods and effects of which he's capable. It may be a sign of maturity, or it may simply mean the band has the luxury to stretch out and spend more time on each project. In the early days Rush never recorded demos.

Whenever they had three weeks off between tours they'd get in there and see how much they could lay down before heading out again. The band now works as hard as ever, but more energy goes into the process of recording rather than busting their asses to break the American market.

Azzoli says the band doesn't necessarily agree with him, but he thinks the change in the group over the last few albums is radical. He says, "The lyrical content and the music reflect their lifestyle. They used to grind it out doing 200 dates a year. Now their families have grown a little, and they've become more reflective of their surroundings.

Lee says the original impetus was to 'cement' a pile of riffs together and get out in front of people. They considered themselves players and wouldn't be caught dead calling themselves anything so pretentious as 'composers'. But with more experience (and more success) they can now afford the time to indulge in something they weren't nearly as concerned with originally, the art of songwriting. Lee says, "It's something we want to excel at. It has really shifted our focus, spending more time doing sketches before the final painting."

Of course, this is Rush we're talking about here, and Lee is at pains to remind everyone that they are still a trio, with all that extra room to get all the licks in. "That's our biggest connection with our hardcore fans, and why we never make top 40 radio. We can write a conventional song, but inevitably there comes that weird part in a strange time signature, or what Andrew Jackson, the respected English arranger who worked on our last album, calls 'the nutty bit'."

What goes around may come back again, surmises Azzoli, because apparently Rush is getting antsy from hanging around the house for so long. They've discovered they don't much like what they're hearing on the radio in their spare time. Azzoli says, "This is the first time Ged's been home for six months straight in 20 years. That's a long time. I dunno what this new album, which will be due out at the end of the year, will be like, but Ged's saying stuff like, 'God is this radio now? Come on! No one's kicking ass anymore! "'

With Lee getting his frustrations pent-up by not touring them out of his system, and Lifeson experiencing a flashback to his past through producing another Anthem act, Clean Slate, the time may be ripe for Rush to shed some of that orchestral skin, now that they've wrapped up the last five years with A Show Of Hands.

Azzoli explains Lifeson's producing role this way: "I wanted him to get back to, 'Hey listen, we got eight dollars to make this record. We can't record in Monserrat and Paris and Istanbul. We got a dingy little studio at 40 dollars an hour. Ya got three weeks. You're not gonna sleep... Remember this?' By doing that he realizes all he's got is a guitar, an amp and a lotta coffee, just like the old days in between tours."

Azzoli says Lifeson got really pumped up with the streamlining of the production process. "He's now in the mood of, 'Hey I got an idea, fuck the outboard gear, I'm back to guitar and fingers!' And Ged's in that mode too, because he's gone back to writing on bass which is, by definition, brasher."

Whichever direction Rush decides to take when they return to recording late this winter, it won't be toward the snoozerama of so much of today's radio. Putting on his fast-talking, record company gunslinger persona, Azzoli moans, "Right now we're in this homogenous zone of the most boring fucking music I've heard in my life. Radio is not listening to the kids, which is a fundamental mistake society is making as well. A 35-year old mother dresses the same way and listens to the same music as her 15-year-old daughter, and that's not right. It's just one big happy consumer group, all sitting around in Polo looking hip."

It's not all doom and gloom, however, because Azzoli figures that the archetypal guitar-bass-drums rock 'n' roll band will never leave the spotlight. He says that this particular concept of music has stood the test of time. "Three guys playing their instruments and expressing their discontent with society will never die, because those three instruments have always been perfect for that emo tional and physical release."

Over the years Rush has pretty much be come an institution, or least a paragon, of the ideal power trio format. Looking back, Lee, says it never even occurred to him that he had a career until a friend pointed it out to him as recently as a couple of years ago. "We always looked upon it as a long term thing, but I never connected that with the idea of 'career' then my friend said, 'You know, you do have a career. A lot of bands break up after a while.' But I guess we're like Sammy Davis Jr. (laughs). He didn't get into it to make couple of records either. That's not to say we'll always be in the public eye, or always be a touring band, but as long as the collaboration between the three people is rewarding, we'll keep at it."