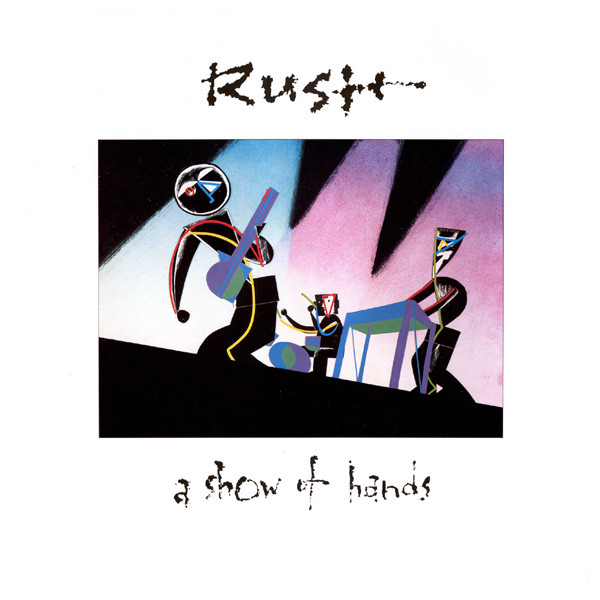

Geddy Lee: Rush To Perfection on 'A Show of Hands'

By Robert L. Doerschuk, Keyboard, March 1989, transcribed by David Copley

Three may be the lucky number for Rush. The trio's latest release, A Show of Hands, marks their third attempt to mix the excitement of concert performance with the cleanliness of studio technology. Their two previous albums left the band feeling unsatisfied: On All the World's a Stage, recorded in 1976, they considered the sound too raw, while Exit Stage Left, from 1981, seemed too slick and overproduced.

But now, according to triple-threat bassist/keyboardist/vocalist Geddy Lee, they've finally got it right. A Show of Hands [Mercury 836346] features the best performances from their last two tours, each recorded with crystalline clarity. "Spontaneity is the most elusive part of performing," he explains. "When you've got a tape machine running during a show, every little thing you do that might not be exact shouts at you and breaks your concentration. We tried to overcome that on this album by taping so many shows that after a while we were bound to get a good one."

Though they captured more than 20 concerts, the bulk of the double album was taken from the last of these gigs. "We played the last three shows in Birmingham, England." Lee recalls. "On the second night, we filmed a live video. It was a major shoot: 12 cameras, 60 people running around backstage. That made us so uptight that on the last concert, after they had been taken away, we felt incredibly relaxed onstage. It was almost like an off night. So we played very naturally."

Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson, and drummer Neil Peart exhibit their usual precision and finesse on Hands, running through a selection of their greatest hits like Michael Jordon icing the Miami Heat defense. Perhaps the most impressive single element on these cuts is Lee's seamless segues between bass guitar and keyboards. Planted behind his PPG Wave 2.2, with a Roland D-50 on one side, a Yamaha KX76 on the other, and a Steinberger bass dangling from his neck, he jumps from strings to keys, keys to strings, while tapping out additional lines on Korg and Moog pedals and singing those trademark stratospheric high notes. Despite the obvious disaster potential, Lee goes through this routine night after night with nary a slip.

"On our Power Windows tour, things got so complicated that I thought it would be impossible to remember everything," he laughs. "So I had color charts made up by a friend of mine. We assigned different colors to each block of the KX76, so when we did, say, `Big Money', I'd flip the chart, and there were these color-coordinated blocks of this synth or that sound. Well it turns out to be a lot easier to memorize than I thought it would be. If you can memorize a thousand notes in a song, it isn't too hard to memorize four different colors."

On some songs, such as "Force Ten," Lee's choreography is so intricate that he's literally dancing. With arms and legs flailing through Rush's typically ornate arrangements, it's obviously harder to play accurately. Fortunately, Lee's KX76 helps him cut down the clinkers. "If I'm going back and forth from playing very fast bass lines to throwing my hands on the keyboard to hit one sound, it's easier to assign that sound to three adjacent notes. That gives me a margin of error. I don't want to worry about being too precise if I'm just triggering a sample. Rather than trying to hit a C in the middle of a frenzied part, I'll assign the same event to the C, D, and E."

Along with his onstage setup, Lee marshals a powerful array of offstage synths and samplers in trying to duplicate the band's rich studio textures. Given the care he puts into orchestrating his parts on record, this is no simple job. On such songs as "Mission," from Hold Your Fire, the arrangements are largely built around synth textures, so approximating them onstage is crucial.

"That whole song was made up of some very complex pads, which added up to what seemed like a very simple sound," Lee remembers. "We had six or seven pads, each one slightly different. I had a choral sound from the [Sequential] Prophet VS, and a slightly higher brassy sound from the DX7. I think [studio keyboardist] Andy Richards added a couple of sounds from his Fairlight and PPG. Then our producer, Peter Collins, recorded an English Brass band playing those chords with their lovely muted sounds. In the final mix, we put all those things together.

"When we do `Mission' live, it's a sample of those chords in combination with three other keyboards I'm playing. It's a really rich sound, and you can hear the vocal quality quite well. Toward the end of the song, I raise it up an octave, and suddenly you can hear the different characters of each keyboard. That `Whiter Shade of Pale' organ sound becomes more prominent too."

Vocal samples abound on Hands as well. "That's an actual 30-voice choir on `Marathon,'" Lee notes. "We didn't want to just use a tape of a choir singing, so we divided the choir up into many different samples. I play a fairly simple keyboard part, but it triggers each segment of the choir sample when we need it. It's a very long chorus at the end, with two key changes, and at each key change the arrangement changes slightly. With the first one, an orchestra joins the choir. For the last one, it's the same choir mixed with some strings. And every three bars or so I'll change a note to bring in another part of the choir. That's a lot of sampling time, so for that tune we had to use three [Akai] S900s."

In past interviews, Lee has modestly quibbled with those who consider him one of the top keyboard players in rock, protesting that his technique has been too rudimentary to warrant serious praise. Now, however, that may be changing, as this fleet-fingered bass player has finally gotten around to taking piano lessons.

"I have to tell you, it's really boring," he admits. "I'm supposed to start each day by practicing the Hanon exercises, doing scales in contrary motion, and that kind of thing. But it's already helping me. The other day, as I was working with a friend on one of his projects, I noticed that my fingers were subconsciously falling onto the right keys for a change."

But why start studying piano now, in this day and age of rapid-fire sequencers? Lee shrugs and laughs. "Maybe it's a reaction to appearing in too many Keyboard polls."