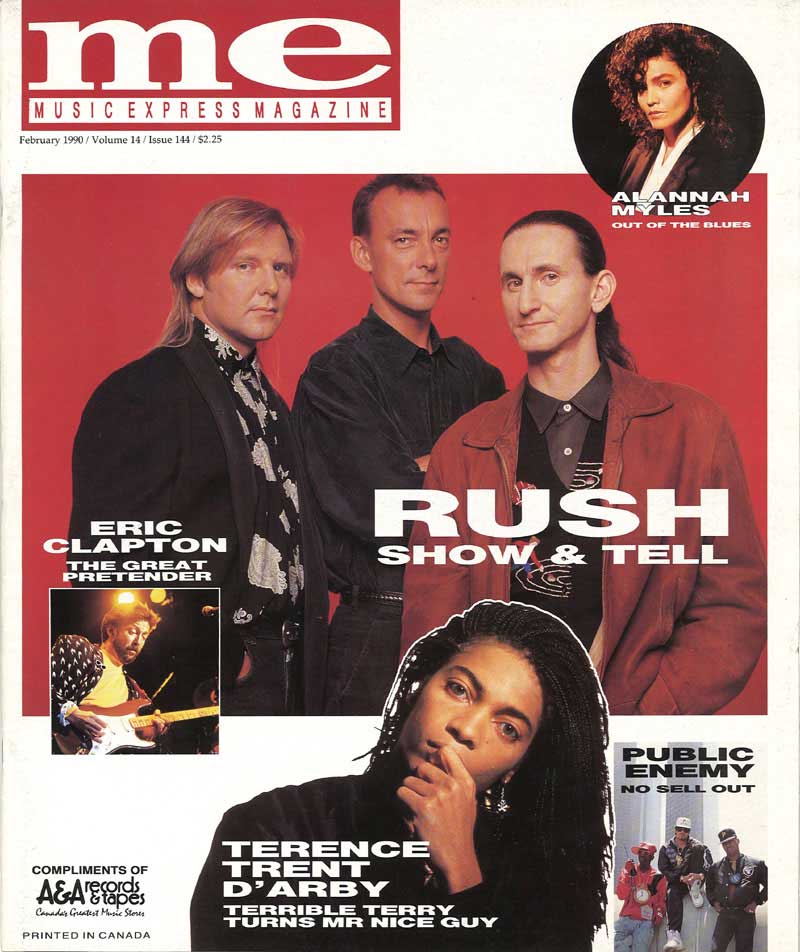

Something Up Their Sleeves

By Keith Sharp, Music Express, Vol.14, Issue 144, February 1990, transcribed by pwrwindows

There's nothing magical or mysterious about the longevity of Rush. Their professional creative approach and insistence on a satisfying life outside the band are paying off as they attack the '90s with a strong album and renewed vigor.

Like the magical implication of its title, Rush's latest release, Presto, has flashed into the U.S. charts with almost stunning swiftness -16 with a bullet after just three weeks. Ironically, though, there was a time when doubts lingered as to whether this, or any future Rush albums for that matter, would ever be recorded.

It was a momentary, almost fleeting time of indecision, and both drummer/lyricist Neil Peart and guitarist Alex Lifeson now downplay the severity of the situation. But in the summer of '88 there was definite skepticism about the trio's future plans.

"I was the most concerned I'd ever been," explains Lifeson as he lounges comfortably amidst the splendor of his majestic mansion, set on a two-acre estate in an exclusive north Toronto suburb.

"We'd just come off tour, we were doing the live album, A Show Of Hands, and everybody was caught at a down point. There seemed to be an air of uncertainty as to whether we were properly motivated to record another album."

From the study of his equally palatial Toronto manor, Peart recalls being less pessimistic about the group's future.

"We had left things in limbo for a period of time after the live album. We agreed not to make a decision and to leave things up in the air," he explains. "It was an open period of our career, our contract with Phonogram had ended, we had no more obligations or deadlines to fulfill. So we decided to get together at my house at the end of December and ask each other, "What do you want to do?"

Since its 1970 inception, Rush has never operated like other bands. From an early stage, they realized that the only way to achieve longevity was by putting their career in a proper perspective. This meant establishing a meaningful and productive social life outside of the band.

As Lifeson has said previously, "Geddy [Lee], Neil and I get together and decide if we want to do a record or a tour. If the answer is yes, then we get on with it. If the answer is no, then we don't. And if we decide one day that there's other things we'd rather do, then no one feels any future obligation to each other."

On a cold, wintry dy in December '88, the trio had come to terms with the band's fate. As Peart remembers it, all three were in good spirits and it soon became obvious that there was still life in the Rush machine.

"We all agreed that we wanted to make another record and from that point everything just flowed naturally," he says. "On the day we were supposed to start writing-we started writing."

"It was amazing how smoothly things went," agrees the blonde-maned guitarist. "Writing and recording albums is usually a tense, stressful period, but this one went amazing well. We were so well prepared that we had the album written, recorded and finished a month ahead of schedule, which for us is unbelievable."

Writing Presto followed the same path as most recent Rush releases. As A Show Of Hands hit the store shelves, the trio ensconced themselves in a rural farmhouse studio, Peart filing through his ledger for lyrical ideas while Lee and Lifeson collaborated on the instrumental arrangements; the trio meeting at the end of the day to see how their individual ideas were matching up.

Peart had previously suggested the title Presto for their live album, but had lost out by democratic process. "So I went and wrote a song called Presto and knew at that point that we had at least an album title to work with."

Unlike some of the heavy-handed lyrical missives of Grace Under Pressure, Power Windows and Hold Your Fire, Presto seems to be a little more diffuse with no overriding theme or message. If anything, the lyrical content is more humanistic and emotional, a return in some ways to the spirit of Permanent Waves and Signals. "Yes, I was conscious that maybe a couple of the last albums were a little on the heavy side, lyrically speaking," allows Peart. "With Presto I took a little looser approach to things. These songs have their own stories and messages without necessarily being linked buy some overall theme."

There is the token ecological in Red Tide but for the most part, the subject matter deals with humanistic matters like cynicism ("Show Don't Tell") and sensory perception ("Available Light"), an ode to Peart's travelling adventures.

"If there is an identifiable lyrical trait here, it's my use of irony, which is injected by acting a character out through the lyrics", Peart says. "For example, in "Hand Over Fist" there are two people walking down the street arguing, and the lead character is saying things which are supposed to be ironic."

The image of Rush clocking in to methodically write new material seems somewhat calculated and mechanical, yet Peart rails at any question of the band's artistic integrity.

"We can't be more creative that locking ourselves away in a farmhouse. I know there is such a thing as inspiration, but I know how to take advantage of it. When we're not rehearsing or writing, I collect ideas and prepare myself for when we do start writing. By the time we're ready to work on a new album, I'm fully prepared. I've got pages and pages of notes to work from."

"Call us efficient, call us mechanical. The point is, when we have to get something done, it's done. That's the only way we know how to work. Maybe we're exceptional in that way. To our mind this is simply being professional."

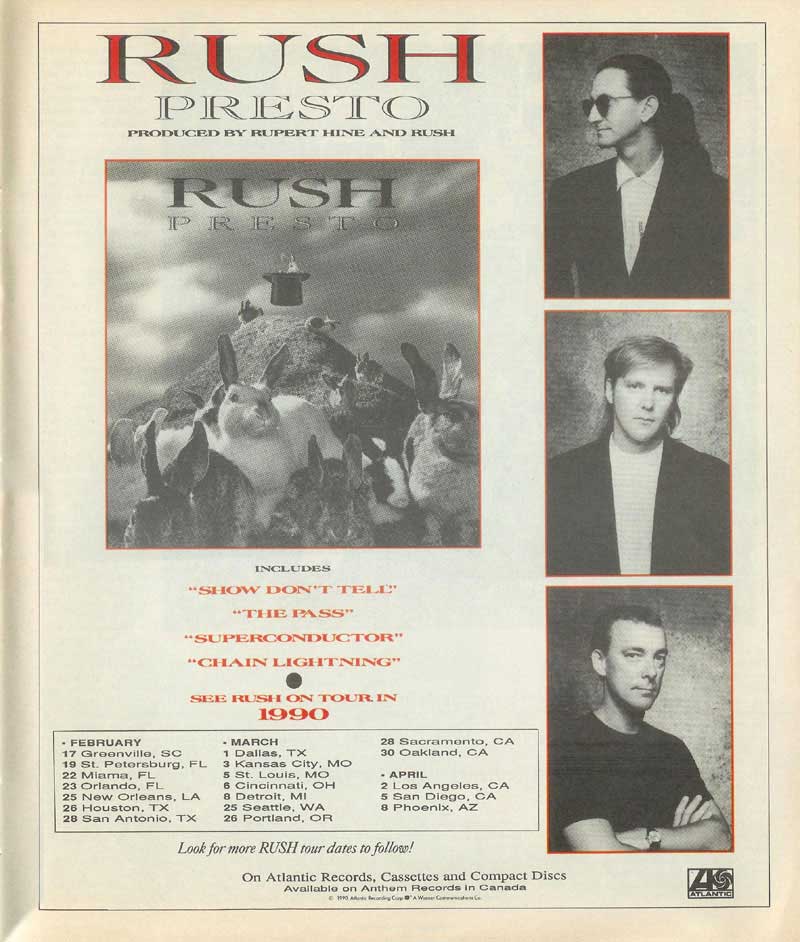

Peter Collins, the producer of the band's last two studio albums, passed on this project, leaving them to seek out a new recruit-Rupert Hine. Hine had initially been approached at the time of Grace Under Pressure, but while he was unavailable for that assignment, he made up for it this time around.

With Rush deciding to record the bed tracks at Quebec's Morin Heights facility and the overdubs at Toronto's McClear Place, it meant Hine and his engineer cohort, Stephen Tayler would be working outside of their England recording base - a rarity for Tayler who's known to be a real family man.

Recording in Canada instead of England, the site of their last two sessions, was a concession the band made to their families. "We're kind of like schoolteachers," declares Peart. "We like to work in the winter and spring and take the summer off with our families. So when we realized we'd have to record during the summer, we set up the sessions so we could at least spend the weekends at home."

In Hine and Tayler, Lifeson and Peart both agree the band couldn't have made better selections. Aside from credits with The Fixx, Howard Jones and Tina Turner, Hine has recorded several of his own albums. His strengths are vocal and keyboard arrangements, elements that aren't exactly band trademarks.

"Our usual practice is to allow one day for the pre-production of each song," explains Lifeson. "So we counted on about 11 days going over the tracks with Rupert. So the first day, we start playing the demos, and he's laughing. We're going 'What's going on?' Rush songs aren't supposed to be humorous! But he said he was laughing because he thought there was nothing for him to do. We went through all 11 songs in one day."

According to Lifeson, Hine developed some interesting vocal arrangement concepts for the band and implemented some strong keyboard elements while actually de-emphasizing their prominence.

As for Tayler, Lifeson calls him "simply the best engineer in the universe. He was so smooth and so efficient, it was incredible. I kept waiting for something to go wrong, but nothing ever did. Because of this, we sailed through the sessions in no time."

As for the end result, Lifeson feels Presto caps off an expressive period that started with Signals, and is a more basic rock album that other recent efforts. "We've probably gained a lot of new fans and lost some of our old ones with the last couple of releases," he says. "With Presto, I think we'll get some of the old ones back."

On a strictly commercial level, Lifeson's observations seem to be correct. With new U.S. label Atlantic making Presto a high-priority item, both the single ("Show Don't Tell") and the album itself are riding high on the U.S. charts-a positive prelude to their next North American tour, which starts this month.

One strange quirk about the new album is that the first side is much longer than the second, forcing Rush to instruct their fans to play the A side much louder to compensate for sound loss.

"You'd think with CD technology that we wouldn't run into these problems, but we still do," bemoans Peart. "We had problems with A Show Of Hands because we wanted the tracks to fit on one CD. That meant we had to leave some tracks off the release, which upset some of our fans. Because of CDs we can now comfortably write longer compositions without having to worry too much about time restrictions. However, a natural running order tends to develop with our albums. This isn't a problem with cassettes, but with albums you're restricted to the time on each side and with CDs you've only got a certain amount of time to play with. So with Presto, the only way we could keep the running order the way we wanted was to put more material on side one than on side two. This means the sound level on the first side is lower that on the second."

As for Presto's immediate impact in the States, Peart and Lifeson are naturally enthused but are adapting a cautious, wait-and-see attitude. They have seen Rush albums fly out of the starting gate only to fade after a couple of weeks.

"That was the main complaint with our previous label," Lifeson notes. "After the initial euphoria when all the hardcore fans were buying the album, the label would never take that extra step to push it further. As a result, sales would drop sharply after the first five or six weeks. This time, though, our new label has something to prove, and I genuinely feel Presto deserves this attention. It's the right album to push Rush into the '90s."

A new album means the inevitable tour, something Lifeson in particular endures more than relishes. It was primarily this factor that put the continued existence of the band in doubt. It's not the actual playing that causes the problems. All three members love the challenge of presenting their new work live to their fans. It's the mind-numbing boredom of the time off-stage: the airport terminals, hotels, concrete arena dressing rooms, the monotonous grind of travelling from one gig to the next.

"We could tolerate it when we were younger and we had to play 300 gigs a year to survive," recounts Lifeson. "But now that we've all got families, it becomes so much harder. It's not so bad for Neil; he's started to work on his travelogues and he goes for a 60-mile cycle to relieve the boredom. For Geddy and I, we try to play tennis or go to a movie or a car show if there's one in town. But it can be really difficult at times. When you're stuck in a place like Topeka or Des Moines and there's nowhere to go, you get a real feeling of helplessness."

Peart and Lifeson say they're mentally up for this tour after taking time off to engage in some exotic exploration. Peart, a known travelholic, has just returned from a cycle tour of West Africa while Lifeson had recently been hiking and scuba diving in Paupa New Guinea.

"They say you go to East Africa for the animals and West Africa for the people-and the people of Togo, Ghana and The Ivory Coast were incredibly friendly," Peart enthuses. "We stayed in the huts with the village chiefs and got to know the people in a way you never could if you were just touring with a band. They thought it was quite a novelty to see a white man playing the drums!"

Lifeson's exploits took him on hikes with people who 20 years ago would have eaten him for breakfast, as well as on reef dives amongst killer sharks.

"You realize that man totally misunderstands the creatures of the sea; I've developed a whole new respect for them," he says. "Sharks actually aren't that dangerous if you respect them. It got to the point that we were actually disappointed if we went on a dive and didn't see something six or seven feet long."

Of significance is an announcement that Rush will court a suitable corporate sponsor for this tour, providing it fits the band's "image". "Like Canadian Tire or Home Hardware [Canadian department stores]," laughs Lifeson. "Yeah, I could have a lot of fun in those stores. Or how about Fred's Plumbing or Bill's Bowling Alley - a totally anti-corporate sponsor? That would be more like us."

Peart, however, is much more somber when broached on the subject. "Corporate sponsorship is a vulgar, abhorrent concept," he says, "which drives up a show's production costs by hundreds of thousands without reflecting the band's true demand.

"There was a time when the onus was on the record companies to provide tour support to break entry-level bands. Now that they have to spend an extra $125,000 or so on videos, the labels are trying to pass the responsibility of sponsorship on to the corporate entity, and that's where things really get dangerous.

"Suddenly the sponsors only want the top-level acts and the ones that are prepared to wear their t-shirts and endorse their products. The entry-level bands don't stand a chance. It's a dangerous situation that's getting worse all the time."

Peart claims Rush has avoided such pitfalls by recognizing their own limitations. They don't play summer football stadium concerts because they know they're not a big enough headline act to pull 50,000 fans - and, besides, it's not conductive to their music. They also don't play countries that don't warrant their interest.

"For us to play places like Eastern Europe, Japan and Australia would be totally self-gratifying," notes Peart. "We know the fans aren't' there, so why bother? And besides, I'd rather see those places on my bike. It's a lot more intimate and a lot more fun."

Both Peart and Lifeson profess dismay at the recent trend towards nostalgic super concerts which have seen the likes of Pink Floyd, The Who, The Rolling Stones and Paul McCartney dominate box office receipts.

"When The Who did their farewell tour in '83," says Lifeson, "I thought, wow, that's a classy way to finish. But five years later it's like, 'Whoops, lads, we're short of money. Let's do another farewell tour.' Same with the Stones. They're not out there for the music. They get their satisfaction from making $60 million."

Nostalgia isn't a tag that can easily be pinned on Rush. Their most recent albums have been even more adventurous than ever and, now that they've survived a mini internal crisis, they seem even more determined to push their music well into the '90s.

"We've been lucky to create a personal chemistry that's lasted so long. Look at any band that's lasted so long. Look at any band that's broken up and it's usually because of personal problems," analyses Peart. "As long as we get that creative gratification from working together, we will continue to produce albums. So long as the band isn't all-encompassing - none of us could ever tolerate that."

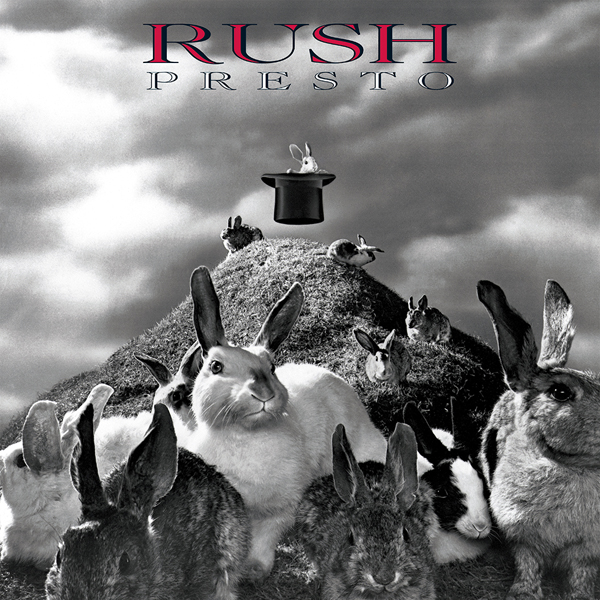

RUSH: Presto

(Anthem/Atlantic)

It's gotten to the point that you don't know what to expect any more from Toronto's favorite trio. In the beginning they were this strange aberration of a heavy metal band with a drummer whose mindset was on Tolkien fantasies (who could forget "By-Tor And The Snowdog") and abstract Ayn Rand doctrines. Later albums would deal with more worldly subject matter and feature more divergent production values. From Signals through Grace Under Pressure, Power Windows and Hold Your Fire, their sophistication and maturity has reached new vistas. No longer a power unit whose lead singer sounded like he'd got his privates caught in a vice, Rush have shown a willingness to take chances and ex-plore new sounds. With producer Peter Collins (Power Windows and Hold Your Fire), the band went to England and utilized Anne Dudley and The Art Of Noise. Vocalist Geddy Lee even dueted with Aimee Mann on "Time Stand Still" (Hold Your Fire's lead-off single). This time out it`s Rupert Hine and his engineer wiz, Steven Tayler, behind the board. The subject matter is less heavy-handed and more concentric, devoid of Peart's usual thematic stamp. Under Hine's direction, the cause and effect experimentation of previous albums has been edited down to its basic elements. What's in place are strong vocal arrangements, powerful percussive and bass underlays, imaginative yet underscored guitar breaks with keyboard fills that bridge the gaps without cluttering the crispness of the individual tracks. Add this to some of the most accessible songs the band has ever created and you've got - dare I say it - arguably the finest piece of work Rush has ever produced. Heady praise, you say'? Well check out the clean simplicity of "Show Don't Tell", the unabashed power of "Superconductor" and Lee's vocal tour de force performance on "Available Light". And yes, Rush have learned to rock again. This may not be Hammersmith Odeon circa 1978 but Alex Lifeson has that metallic bite back in his guitar and Peart's drumming has rarely been so precise and uncluttered. At a time when nostalgia reigns, it`s refreshing to know a band of Rush's stature is still prepared to take chances and pull a platinum album out of their hat. Magic indeed!

K.S. ****

(four stars)