Presto Change-O

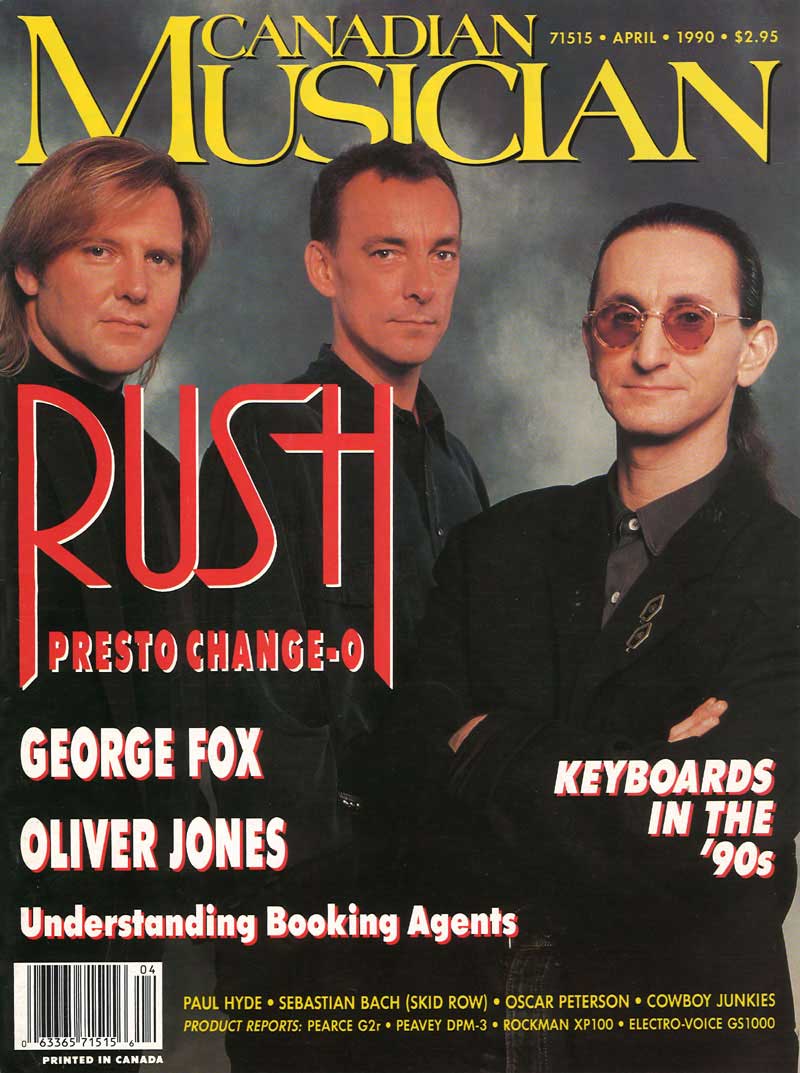

By Nick Krewen, Canadian Musician, April 1990

Is it a coincidence that Rush's best-selling album is a back-to-basics masterpiece that was written and recorded with "real" instruments and relies on traditional elements like melody and feel? The eighties, doomed to be remembered as the age of technological overkill, really are over.

Oh, those wascally wabbits that adorn the cover of the latest Rush album, Presto. They're everywhere they shouldn't be.

After escaping the confinements of a magician's chapeau - curiously suspended in mid-air - the bevy of bunnies is having a grand old time, munching grass and generally sniffing out new territory.

It's no mere coincidence that the same parallels connotated by the Hugh Syme cover art can be drawn to the lengthy and successful career of Rush, Toronto's megapower rock trio, whose superconducting of intellectual analysis within the designs of contemporary rock concepts has been nothing short of revolutionary.

For compatriots Geddy Lee, Alex Lifeson and Neil Peart have seemingly had to pull rabbits from their hats and wave their magical wands in order to overcome obstacles placed in their paths - from reluctant radio programmers to resistant rock critics. Through inexhaustive toil and spirit, relentless determination and a touring schedule that would stunt hair growth and promote curvature of the spine under normal circumstances, Rush has captured the unwavering loyalty and well-earned respect of music lovers around the globe - to the point where their worldwide sales for sixteen albums over a recording profession spanning seventeen years has topped the thirty million mark.

More significantly, some of those defiant ivory towers that once stood immobile to the band's musical overtures are now teetering and crumbling. The reason? Presto.

Buoyed by new North American distribution agreements with Atlantic Records in the U.S. and CBS in Canda, Presto's sales figures have been skyrocketing since the starter pistol's been fired. Even radio has been cheering: the lead-off track, the put-your-money-where-your-mouth-is anthem "Show Don't Tell", topped the persnickety Album Rock Tracks chart of music industry bible Billboard as the most played rock radio song in the northern Hemisphere for a couple of weeks.

But just the general feel of Presto is enough to allow Geddy Lee, the shrill-voiced multifaceted architect who manages to co-ordinate bass playing, lead vocal and keyboard duties without imploding, to wax optimistic.

"Presto is kind of a renewal to me," says the Toronto-born Lee, thirty-six. "It's a renewal of energy and a positive outlook, in musical terms and in personal terms, both in my place in the hand and my feeling about recording."

Recorded last summer at Le Studio in Morin Heights. Quebec, and McClear Place in Toronto - and mixed at London's Metropolis Studio with coproducer Rupert Hine (Tine Turner, The Fixx) Lee said the focus of the album was decided within the seeds of its creation.

"From the word go, there was an emphasis on strong melodies and rich choruses," explains Lee. "We wanted it to be more of a singer's album, and I think you'll notice that the arrangements musically support the vocal."

Neil Peart, the professor of polyrhythms and Rush's resident prosemaster, also notices a difference about the new record.

"Presto doesn't have a thematic message," he states. "There is no manifesto, although there are many threads and a strong motif of looking at life today and trying to act inside it."

Humanity and the different aspects of human nature have formed the basis of several Rush albums - A Farewell To Kings and Grace Under Pressure among them - but rarely has the listener been able to make the connection so clearly with the introspective nature of "Scars"" or the ecological alert Hashed by "Red Tide".

"Neil's lyrics to me are a lot more heartfelt," acknowledges Lee, who with his counterparts have been nominated for a Juno Award for Producer Of The Year. "Presently, they're experience-oriented. I think they deal with living, and I find them inspirational because I think they're still ambitious. Whenever he's written something good, I feel it's more emotional."

The Hamilton-born Peart, 37, has blazed a literary path for Rush since he joined the band in '74 after original drummer John Rutsey departed for health reasons. Ironically, his talents as a wordsmith were largely undiscovered - even by Peart himself.

"We had no clue whatsoever that Neil would be a lyricist," said Lee, speaking for himself and guitarist Alex Lifeson. "He joined the hand strictly on his percussive skills. He was in the hand less than two weeks before our first U.S. tour. It was as we were getting to know each other on the road that Alex and I noticed a few differences.

"Alex and I were teenage idiots together, but we didn't know who this strange creature was. We did notice his incredible appetite for books and for reading.

"He also spoke English better than anyone we knew - in fact, better than anyone we had ever met," recalls Lee.

Geddy maintains the duo suggested Neil try his hand at writing, but Peart has a different recollection.

"I don't think anybody ever asked me," he said." I think I became lyricist by default. I saw a vacuum and worked on a couple of things that I submitted and were accepted."

Inspired by socialist author Ayn Rand, Neil Peart became the catalyst for establishing Rush as master musical interpreters of literary giants, and for teleporting certain ideas into the stream of rock consciousness.

Further adaptations of Rand's work - as in Caress Of Steel's "The Fountain Of Lamneth" suite and the futuristic sci-fi fantasy epic 2112 - were creative forays that expressed a thirst for knowledge. Cliffhanger adventures like those of "Cygnus X-l". which was begun on A Farewell To Kings and concluded on Hemispheres, challenged the imaginations of fans who were tired of well-worn rock cliches.

"Initially, lyrics were never that important to me, internally or externally," confesses Peart. "But dealing with words changed the way I read, and introduced me to some new worlds.

"It's also important that you see different points of view. I've read a lot of American literature from the '20s and '30s, and what was interesting was that all the authors of the time - Hemingway, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald and Faulkner - saw it all so differently. yet they manage to strike at some universal theme.

"It's important to be conversant with other people's views, even if you don't agree with them."

Notwithstanding Peart's gift with words, Alex Lifeson's fabulous fretwork and intricate bass playing from Lee, Rush's self-confessed baseball fanatic. Geddy also feels that the band's personal objectives played a large part in their early success.

"We had lofty ambitions," notes Lee. "I think, at that age, you have visions of rock glory. Neil's lyrics dealt with things that appealed to our sensibility - a noble kind of rock 'n' roll. It was always a bone of contention that there was a kind of integrity about them that was great to stand behind.

"It feels very good as a young band to feel you're doing something important. It's a motivating factor."

When it comes to composition, Lee says he and Lifeson split responsibilities, but balance each other out.

"The two of us take on many different roles," Lee explains. "If Alex has a strong idea that's very complete, I will act as the producer/editor. For instance, with 'Show Don't Tell.' Alex came to me with a guitar riff that didn't need to be touched. I contributed the chorus and we worked on the verses together.

"We each have our own different strengths. It works both ways and it's like a puzzle. Sometimes Alex and I even forget about writing the music ahead of time. A song like 'The Pass' needed to be written to the lyrics, which we used as a script."

Lee says the most satisfaction he gets from working on Rush albums these days is as a composer.

"Most rewarding to me is the writing," said Lee. "It's the single most interesting thing I do. Everything else is downhill after the song is written. It's really the challenge.

"There used to be a lot more emphasis on the playing. but now it's very much the writing and arranging. It's a tremendous challenge and one that never grows old. You always think you have a better song in you than the one you just wrote. And there's always the tremendous fear of what if nothing comes out? What if the well goes dry?"

Lee admits he's satisfied with Presto but then cautions that "You always feel much more positively about the last one you did."

Specifically for Presto, Lee said Rush decided to streamline the sound and steer away from synthesizers.

"We wanted to stay away from keyboards for this album," acknowledges Lee. "They can be quite a passive writing tool, and we wanted something more forceful and less pastoral. I wrote a lot more on bass, which reminded me of the old days when there was nothing more to write on.

"This album was a real reaction against technology in a sense. I was getting sick and tired of working with computers and synthesizers. Fortunately, so was Rupert. We were united in our rebellion, and decided to use a more organic approach. We made a pact to stay away from strings, pianos and organs - to stay away from digital technology. In the end, we couldn't resist using them for colour."

Lee also underlined the importance of Rupert Hine's involvement during the Presto sessions.

"He felt very strongly about the material," Lee asserts. "He didn't feel it necessary to force any of his ideas on us. He very much operated within the philosophy of 'if something works, don't fix it.'"

Apparently an extra set of ears were also appreciated in the studio.

"Very early in the writing, Rupert pointed out a few tendencies we had as writers which later proved to be important. Sometimes all you need is to be shown where you're going, by someone objective, just to remind you that you have millions of options.

"Because we're players - when we record we tend to go after perfect performances. That's not an area Rupert feels is important. We have a tendency to be so precise. It was very easy for us to get into a machine-like mode. We get so perfectly tight in synch that when we fall short, it hits our ear like an error."

Peart - who often sketches ideas out in a notebook before bringing them into the studio during preproduction - says he's unwilling to improvise for an album without being prepared.

"I'm not ready to do it," he confesses. "It took me so long to develop confidence and facility. Luckily, I'm not forced to publish or perish. so I always like the situation of refining what I have."

He refuses to cast a critical eye on his past efforts, although he admits he isn't perfect.

"There are tons of little bits I can't listen to without wincing," says Peart. "But there are no big mistakes in integrity or ethics, so you can't reproach yourself. They all fed something, and as long as you're satisfied with your current work, its purpose has been served. I don't think everything we've done is great."

Rather than name favorites, Peart feels his best lyrics are songs that have been landmarks as creative achievements.

"'Vital Signs' was a pivotal point in Rush's career," said Neil. "It was the first time we tried a new style, which worked. 'Subdivisions' marked the first time I could be graphic and autobiographical. 'The Analog Kid' was my first attempt at non-fiction. For the longest time I stepped into characters until I had my own confidence and technique to be able to step outside them as a writer."

"For 'Show Don't Tell' I adopted an attitude and character," Peart reveals. "I took a stance and a good attitude and developed it. I think it's just a sense of growing power in my own confidence and ability. I hope it reflects growing technique. I find a trend for us since Grace Under Pressure has been cutting off abstractions.

"The song 'Presto' reflects me and life as a theme, although I invented the scenario. Irony is also a tool I used on this album. Most times I was careful not to dramatize the situation. When you step into true fiction, you use the fiction to explain the truth and reality."

Currently in the midst of a North American tour that hits Canada in May, both Lee and Peart feel the question of Rush grinding to a halt is an obsolete one.

"There are a lot of challenges left," said Peart. "I'm still learning how to say personal things in an effective way - and I see this vast ocean in front of me."

Lee states that the only thing that will stop Rush from continuing is public demand.

"I don't see there being any reason to stop," Lee declares. "I think the age barrier in rock 'n' roll has gone. I think the bottom line is whether or not you sell records. If you stop selling, that can hasten the demise of any creative outfit."