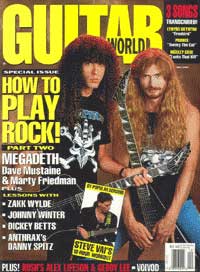

Alex Lifeson & Geddy Lee: Flesh And Bones

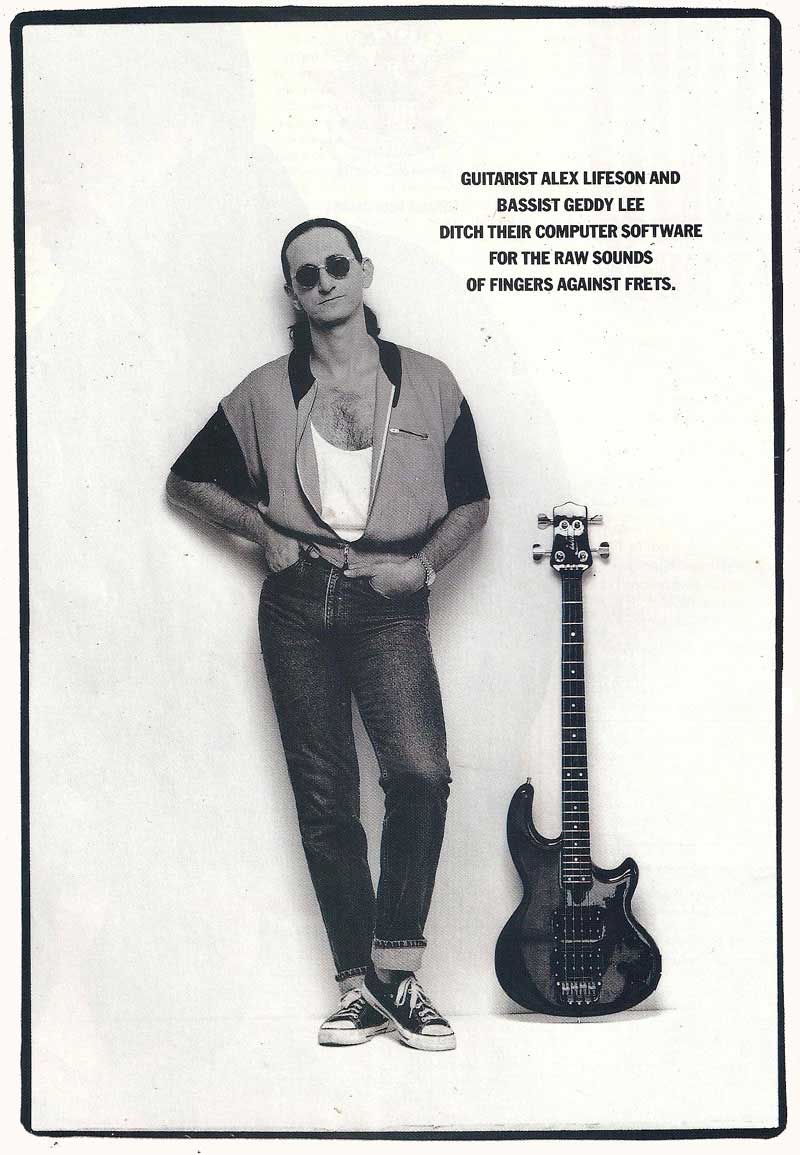

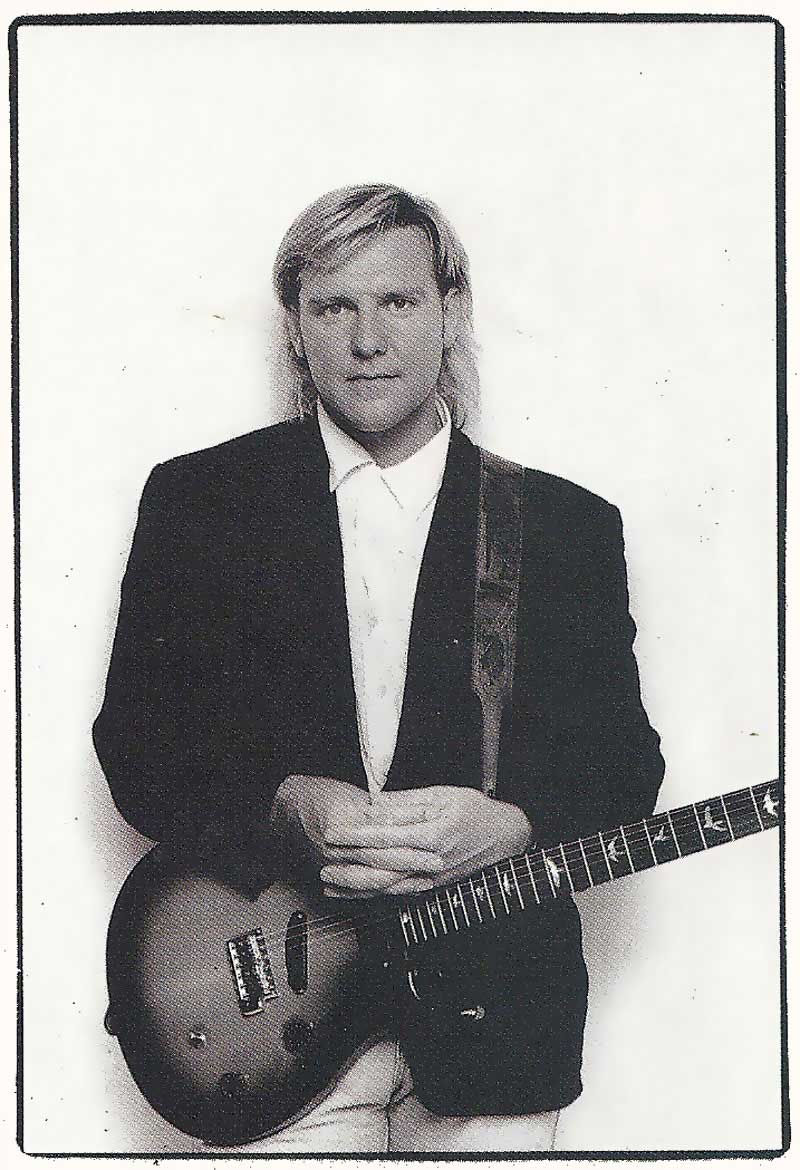

Guitarist Alex Lifeson And Bassist Geddy Lee Ditch Their Computer Software For The Raw Sounds Of Fingers Against Frets

By Mike Mettler, Photography by Andrew MacNaughtan, Guitar World, December 1991, transcribed by pwrwindows

"I'M A CLASSIC TINKERER," says Rush bassist Geddy Lee. "At some point, somebody has got to come up to me and say, 'Let go of this song, Geddy - now. It's finished.' Otherwise, I'll fiddle forever."

Fans of the band's classic, late-Seventies guitar-driven format will be relieved to discover that Lee focused his Mr. Fix-it obsessions primarily on his vocals and Wal bass rather than his Macintosh computer. Roll The Bones, Rush's 14th studio album, reaffirms the group's unstated policy of distancing itself from the lush keyboards that dominated its mid-Eighties sound.

Getting out of its mini-MIDI slump was no cakewalk, but Rush was in good hands. During the band's 1989 Presto sessions, producer Rupert Hine and engineer Stephen W. Tayler helped Lee, Lifeson and company return to their roots - the power-chord heavy arrangements that originally made the band great.

"We wanted them to loosen up a bit, and roughen up their sound," says Tayler. "Basically, we wanted them to sound like a three-piece rather than a three-piece with a sequencer."

Presto's harder edge proved to be such a success, yielding the hit single "Show Don't Tell" and the supercharged "Superconductor," that the band decided to again solicit the services of Hine and Tayler.

But before the production team arrived, the trio convened for 10 weeks of pre-production at an isolated studio located on farmland in northern Ontario. Lee and Lifeson toiled over the music while drummer Neil Peart penned the lyrics. Lifeson arrived with tapes of ideas he had demoed on a Tascam 238 eight-track in his home studio. These included several home-grown solos that actually made it to the final mix, including those on "Bravado," "Ghost Of A Chance" and "Roll The Bones." Not surprisingly, he is particularly proud of those solos.

"Maybe I should work on my own a little more," Lifeson muses. "I think those solos reflect the freedom that comes from being behind the console myself. For instance, on 'Bravado,' I achieved a very different sound. It's almost countryish - definitely not a hard rock sound. I did that on my Telecaster. Whenever I applied a little vibrato, you could hear the string rubbing against the fret and the fingerboard. That's a very real, honest sound which appealed to me. And the background music provided a great emotional platform for me to solo over."

The many "emotional platforms" that crop up throughout Bones, created enough appropriately varied musical moods to convey Peart's often profound, occasionally ambiguous lyrics. Lee's vocals, oft-maligned for being a bit too grating, display a similar emotional range. During the last few years, he has worked hard with his voice, developing a knack for writing true vocal melodies. In the process, he's made quite an admirer out of Lifeson.

"In the early days, it was a trademark of the band for Geddy to be a screamer," Lifeson says. "But it was a terrific strain on his throat to sing like that. Now he wants to be more of a pure singer, and he's worked hard at it. His sense of melody and harmony have really developed over the last few records. On Bones, he sings in a lower register than he has before, and he is more controlled. And this has changed the way we write songs. We used to just tack on the vocals as afterthoughts, but now I'm aware of the vocal melody a lot earlier, and can react accordingly to it with my guitar parts."

Lee's bass sound has also warmed considerably, courtesy of a modified red Wal bass he discovered during the Bones sessions, which now shares duty with the black Wal he first employed on Presto. "The body shape is different," Lee says. "It has a bit more of a horn on top and it really does have a bigger, slightly deeper and warmer sound. When we started writing this album, I fell in love with the sound of the new Wal; it gave us a slightly different sound, replacing my usual clanginess with a warmer bottom end."

"Dreamline" is one song that benefits from the black Wal's distinctive twanginess. "I play a lot of chords there," Lee says, "especially during the bridges, so that the bass takes on the characteristic of a rhythm guitar, making it even harder to pick out the individual notes."

Yet another unexpected development emerged from the Bones sessions: Alex Lifeson, master of chords and chorus, can play the blues. Though this funkier side of him hasn't been in much evidence on his previous recorded efforts, Lifeson says the blues come naturally to him.

"Believe it or not, that's where my roots are. I played the blues when we started out on the bar circuit. But that style never sneaked into Rush's music as much as I would have liked."

For evidence of his blues prowess, listen to the solo on "Ghost Of A Chance," in which he coaxes a fuzzy, grunge-laden tone from his signature Paul Reed Smith. Lifeson says this moving solo was originally recorded as a throwaway on a second-take demo.

"I just played that to fill space in the allotted solo section. It was the last thing I had to do for the day. It was very late, we were very tired and the lights were all turned down. And it just worked - everything clicked. Neil picked up on some of my triplets - he later went back and based his drum pattern for the whole song around my demo solo - and his playing really set me off.

"Then, when it came time to cut the real solo, I wanted to duplicate that demo - and I just couldn't do it. First of all, I wasn't able to recapture the demo's tonal quality because that Tascam has a specific sound that's hard to achieve anywhere else - just in the way the EQ runs and the compression is on that strip of tape. Furthermore, it's almost impossible to duplicate an unplanned moment where everything comes together. So we used the demo solo, and all those elements provided it with a very distinctive feel. I love that solo."

Lee concurs that "Ghost" is a grabber. "It's one of my favorite guitar songs on the record," he says. "That song's solo and outro are among the best things Alex has ever played. It's just very expressive guitar playing."

If "Ghost"'s emotional content will raise a few eyebrows, then the title track is certain to turn heads with its funky groove. Throughout the song, Lee's red Wal bounds tightly over Peart's booming bass drum. "Plus," adds Lee, "at the bridges it becomes very frantic and difficult to play - just what we love to do. The choruses have a nice texture, which is created by the way the vocals and acoustic guitars all come together. And that whole middle section is way outside - that was a lot of fun to do."

That "middle section" is the techno rap that suddenly pops up after what is a typical Rush chorus. This inner city-flavored departure from Rush's usual thang is sung by - whom? Neither Lee nor Lifeson is talking. "It's a mystery, dude," Lee says with a devious smile. "All I'll say is that it was from within the band."

Tayler, at least, supplied the technical particulars: "The mystery vocal was processed through an Eventide UltraHarmonizer to make the rapper sound bigger and blacker than he actually is. Though the rap sounds very up-front and very electronic, the music sections around it are quite ambient, with real bass, real drums, and real guitars. It was made to sound very organic."

Bones offers some more surprises. Old line Rushophiles will be pleased to note that "What's My Thing?" is the first instrumental jam offered up by the band since "YYZ," from 1981's classic Moving Pictures. "Thing" is a quirky workout with rata-tat keyboards and uplifting choruses.

"A friend of mine said it reminded him of a really perverted version of 'TelStar,"' says Lee. "I really like it, but it almost didn't make it onto the record. Though it was a lot of fun, it was also very difficult to get together. Every time we started writing it, it turned into another song. I usually keep extra lyrics lying around while I'm writing the music. If I get into a great groove I'll look at the lyric sheet and realize, 'Hey, this lyric really fits with this music,' and poof, there goes the instrumental.

"But Neil finally said, 'You've been promising me an instrumental for two years. I'm not giving you any more lyrics until you cough it up.'"

"Rather than making 'Thing' just a showcase for our playing ability," adds Lifeson, "we came up with a genuine song that has a verse section, chorus and bridge. It's got a theme that's answered by the guitar, which makes it quite majestic. I also like the passage, near the end, where the organ echoes the melody of the guitar solo. And there's a good heavy section where I throw in the extra note to throw off the time signature - something I have to do. My solo is more atmospheric than anything else."

"Atmospheric" is a good way to describe many of Lifeson's recent solos, as the band has progressed beyond the seven-minute crunchers of its "Working Man"-days. "Remember, I'm not 22-years-old anymore," Lifeson says. "I'm 37. To repeat things I did 15 years ago is not my aim. It's nice to be reminded of certain moments of the past, but I want to move ahead."

Lee feels the same way. "Alex is a great soloist, and a lot of people want to hear him wind out every time. But you can't repeat yourself constantly and still feel satisfied about what you're doing."

What this signifies for the Rush of the Nineties is a dedicated quest for fresh new sounds and fresh new instrumentally dedicated approaches. One such update, says Lee, is Lifeson's thick, sustained tone on "The Big Wheel." "He tried something - a finger-picked solo - that was very subtle, texturally. That isn't very easy to do, because it's not as obvious as a screaming solo."

A change in approach can sometimes be something as simple as picking up a different guitar. For "The Big Wheel," Lifeson used a modified Strat with a Shark neck and a Bill Lawrence L-500 bridge pickup, which makes it "sustain for months."

Despite its progressive mindset, Rush has no plans to totally abandon the approach that has sustained seventeen years of rock and roll success. "We're the kind of band that likes to evolve," Lee says. "But we'd feel uncomfortable if we dropped our hard-rock roots. Believe me, when we want to get tough, we still can."

Constant evolution, Lee adds, has been vital in keeping Rush together after all these years. "We like to see how many textures we can add, different ways to explore sophisticated vocal approaches, keyboard techniques, unusual chord inversions, or textural moments. There doesn't seem to be anybody else trying to develop the hard-rock sound, except for maybe Metallica. So we do what we can - especially on our albums. In concert, there's very little room for improvisation - I've got two Virgos in my band who are neatness freaks, and they like their sets to be highly organized - but there's a reason why 'Closer To The Heart' has remained in the set for so long: when we get to the middle section, we have no idea what we're going to do next."

Lifeson readily admits that he prefers to faithfully recreate the sounds captured on the band's recordings on stage. "Personally, I was always disappointed when I went to see bands live and didn't hear things the way I remembered them from the record. The thing that makes it different is the added bonus of the energy and excitement that surrounds a live show.

"Our last few albums have become a lot more complex, and it takes hard work and even harder concentration to achieve the goal of sounding like the three-piece band we are on record. But we've always made our records with the intention of playing them live. So we're heading out there again."

In concert, Lifeson plays the Paul Reed Smith EG4 that he used throughout Bones. "It's based on a Strat," the Rush riffer says. "And it's just a great guitar. It's got a humbucker and two Strat-like single coil pickups and melds the Gibson toughness with the Fender clarity."

Such flexibility allows Lifeson to change sounds without switching axes. "I can go to a clean pickup for quiet, arpeggiated passages - or anything that needs to be clean - and then I can immediately go to something very heavy and grungey without having to step on a myriad of distortion pedals."

On the acoustic front, Lifeson split his Roll The Bones work among a Washburn, a Gibson Dove and a Gibson G-55. "The Dove has a very soft, compact sound," he says. "And the Washburn is loud and jangly. Combining those two and adding the G-55 in a Nashville tuning on top is really nice; it's 12-stringish, but not overwhelmingly so." In concert, however, Lifeson plays his Ovation, which he calls "the most easily controlled acoustic."

He says that on this tour he will stick with the Crown amplifiers he began using several years ago. "I switched from Mesa/Boogie because they were a little too dirty for me, and I was sick of having to change the tubes all the time. In going to the solid-state Crown Macro Series, I found the top-end was cleaned up. I also have found the Crown to be very dependable."

Other features of Lifeson's rig include a GK preamp, two t.c. electronic 2290's, a t.c. 1210 for chorus, a Roland DEP-5 for reverb, a Roland GP-16, and a Digitech IPS-33 for 12-string effects and harmonizing.

While Lifeson continues to try out new gear, always expanding and altering his rig, Lee is much more static in terms of equipment: his idea of change is adding the red Wal to his black Wal.

"Geddy's had the same setup for years," Lifeson says with a laugh. "And now that he's paid it off, he'll never change."

"It remains the same," Lee confirms. "The same pair of BGW 750 power amps, a couple of Furman PQ-3 preamps - the usual." Lee's usual also includes a Telex wireless, API 550 EQ, an Ampeg V4B bottom, and a Tiel double 15-inch bottom. Custom switching allows Lee to move from the Furmans to the API for different tones.

Lee maintains that no matter what he does, his onstage amps don't make much of a dent in Rush's live wall of sound. "A lot of what people hear out in the audience has absolutely nothing to do with my amps," he says. "They've become almost just a monitor for me. A lot of the sound is the EQ the house engineer puts on, and mostly what you get is a straight Wal sound with a bit of amp grunge mixed in."

Lee pauses before revealing his secret fantasy: "At this point, I could probably get away with just using a tiny little GK amp."