Updating The Rush File - Rush Rolling Along On Low-Profile Fame

By Peter Howell, Toronto Star, December 13, 1991, transcribed by pwrwindows

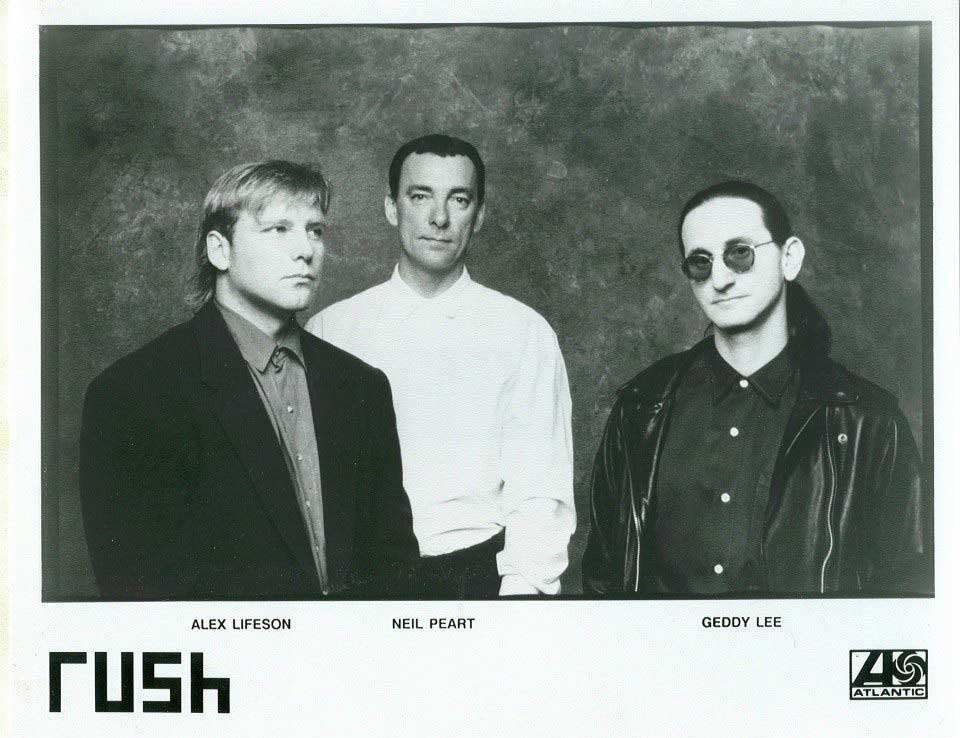

Geddy Lee, Neil Peart and Alex Lifeson. Just yer average Canadian rock hosers, guys who have been playing in the band Rush for so long, they don't know when to quit.

Right?

So then who are these superstar guys who have:

- Sold more than 30 million records in 17 years, a feat unmatched in the annals of Canadian rock?

- Seen their current LP debut at the No. 3 spot on the influential Billboard Top 200 Albums chart. It's the best debut in the band's history, and the highest Billboard entry this year for a Canadian artist, beating even the headline-grabbing Bryan Adams?

- Earned gold certification in both Canada and the United States for each of their 18 albums, and have also received many platinum and multi-platinum discs?

- Played two sold-out shows last week in New York's Madison Square Garden, winning the venue's prestigious Golden Ticket Award, which recognizes sales in excess of 100,000 tickets. They've also done two-nighters in Detroit, Cleveland and Philadelphia and there are two shows scheduled for Los Angeles?

The answer to the rhetorical question is the very same three chaps - Lee, 38, Peart, 39, and Lifeson, 38, the almost-anonymous Toronto musicians who have turned the phenomenon called Rush into one of Canada's most successful cultural exports.

Despite the band's to-die-for track record, the group has a public profile far lower than such Johnny-come-lately hard rock outfits like Guns N' Roses, Skid Row and Metallica, which have all recently had cover star treatment in Rolling Stone.

The Gunners also recently received major advance ink in the New York Times for their own two-night stand at Madison Square Garden, which followed the Rush two-nighter that the Times didn't advance.

Rush, which plays the hometown Maple Leaf Gardens on Monday, has never made the cover of Rolling Stone, and the group's albums - including the superlative new release Roll The Bones - are routinely trashed by rock critics who still labor under the prehistoric notion that Rush is a heavy metal band.

The latest slag came from People, which called the group "Rushosaurus" and recommended they "roll these bones into a museum - say, an FM oldies station."

The band has also had less respect and recognition in Canada than would seem its due. The group has been nominated for 35 Juno Awards since 1974 but has only won six and it has never won a cutting-edge CASBY Award.

Rush did well at the recent Toronto Music Awards, picking up trophies for bassist/lead vocalist Lee and drummer/lyricist Peart.

But while it was honored for having the best international success by a Toronto band, Rush wasn't even nominated for best Toronto group, even though the Tragically Hip - a band from Kingston - was nominated in both categories.

Then there's the slightly-less-than-spectacular ticket sales for Rush's big Toronto homecoming show Monday at the Gardens, where the band is playing for only a single night.

There are still about 2,500 tickets available for the concert, even though the Tragically Hip was added as an extra draw.

(The event will aid the United Way and the Daily Bread Food Bank. A minimum of $7 from every ticket sold will go to the United Way, and concert-goers have been asked to bring cans of food with them as a donation to the food bank.)

"It's a strange thing," says Peart from a Providence, R.I, tour stop, as he ponders why the band is apparently bigger stateside than in Canada.

"It's a little bit of that old Canadian apathy, I think.

"Times are tough in both countries, but American kids who are strapped for cash will say, 'I'm going to that show, even if I have to wash dad's car five times to get the money.'

"Canadians will say, 'Well, it's a bit too much trouble and I really can't afford it'."

But both Peart and Lee have long since grown past the stage where they fret about their public image, or why bands like Guns N' Roses dominate the rock press.

"We have certainly never dwelt in the mainstream, and continue not to," Peart says.

"We entered what a friend calls 'the aura of trendiness' back in 1981, when our Moving Pictures album sold so well, and our concert attendance doubled. Within a year it had died down to our normal level, and it's not likely we'll re-enter the aura of trendiness again.

"But the bands that I admire are not in the mainstream - bands like the Rheostatics, who are Canada's answer to R.E.M., but without the attitude.

"And it's the same of all art; it's never the mainstream that offers the thrust of things, whether it's music, or painting or literature."

Adds Lee: "Guns N' Roses are a lifestyle band, and we're not. There's different kinds of bands that work in different kind of magazines, like Rolling Stone and Spin, and it makes perfect sense to me that we're not that kind of act.

"There's a friend of ours in New York who's in with a circle of critics.

"And for years he's told us how unpopular it is to like certain bands, and we're one of them."

By "lifestyle band" Lee means Rush is not the type of outfit that is likely to touch off a riot, as the Gunners did in St. Louis this past summer when lead singer Axl Rose jumped off the stage to attack an obnoxious fan.

Lee, Peart and Lifeson, who are all married with kids and who all still live in Toronto, have never been ones for attention-getting rock star stunts.

In fact, when Peart and Lee are asked if there was ever a period in Rush's history when the band really tried to act as heavy metal monsters, the two have to figuratively scratch their heads to come up with a reply.

"I kicked a cassette player to death one time," offers Peart, warming to the recollection of an occasion when he yielded to the unfamiliar affliction known as Major Rock Star Tantrum.

"I had just had a bad show, on a night when the entire mechanical and electronic world seemed to be conspiring against me.

"I just wanted to come out to the bus and listen to some music and console myself.

"And the stupid cassette player wouldn't work. I thought, 'Okay, I'm going to kick the living s--t out of this thing.' I did, and I felt better."

As for Lee, he can recall a time in Rush's green years when the band "had to pay for a few hotel rooms" because of damage caused by heavy partying.

But, he quickly adds, that occurred because the trio was the opening act for such masters of mayhem as KISS and Aerosmith.

"We may have crazy-glued a few telephones down, but I don't think we ever threw anything out of windows," Lee says.

"I think we looked at ourselves more as pupils, watching people like KISS and Aerosmith, and trying to learn how to exist on the road.

"It soon became apparent to us after surviving on the road for five or six years that you have to pick and choose your times to party, otherwise you won't survive."

Peart's wrangle with his Walkman and Lee's telephone vandalism doesn't quite match the wretched rocker antics of Axl Rose heaving a piano through his own picture window, Elvis Presley shooting out TV screens or Keith Moon driving cars into swimming pools.

But it's the shortage of such stories from the Rush crew that explains why the band has survived for 17 years, in an industry that seems to conspire against longevity.

Moderation in all things is the guiding force that moves these like-minded musicians- cum-philosophers, along with the companion virtues of modesty, dependability, a keen sense of professionalism and a willingness to compromise.

Unlike many major acts, the members of Rush will stay at a hall from the time they do their afternoon sound check right until showtime, as a hedge against the possibility that one of them might get delayed in traffic later and keep the fans waiting.

The group also opts for long sound checks, both for itself and its opening act, because "we were an opening act for a long time, and we remember how it felt to be screwed by a headliner, and just be tossed onto the stage at the last possible moment," Lee says.

"To us, any other behavior than how we do it is unprofessional, and being unprofessional is the ultimate shame."

The most-asked question of Rush these days is how the band has managed to stay together for 17 years, along with their faithful manager, Ray Danniels.

In fact, the partnership between Toronto-born Lee and Lifeson dates back to 1968, a period Lee calls "pre-history," when they started jamming together in a Willowdale basement.

And the group's first album in 1974 featured John Rutsey on drums, although he left the band and was replaced by the St. Catharines-bred Peart before Rush toured with the album.

"It's something about our nature that keeps the three of us together," Lee reflects.

"All of us are involved in long-term relationship with our wives and families, relationships that are outside the band. So there's something in our nature that makes us unwilling to give up the fight, in one sense.

"There's also a lot of give-and-take. We share a lot of things together, and our sense of humor has grown together.

"In fact, I think our sense of humor probably has a lot to do with us still being together after all these years. We still have a lot of fun with each other, and I think that's something that's kind of underestimated in a friendship."

Rush has long been known for its musical efficiency and economy, even though its songs have on occasion strayed toward progressive rock pompousness.

Each band member has several roles: Lee on vocals, bass and synthesizer; Peart on drums, percussion and lyric writing; Lifeson on guitar, synthesizer and back-up vocals.

As composers, they work together so closely "it surprises us at how in synch we are," Lee says.

The one thing that chafes the band members is to still be tagged as "heavy metal," because the term ignores the fact that Rush has mixed everything from reggae and ska to funk and rap into its sound, as an early innovator of the now-trendy practice by bands to integrate musical styles.

Groups as diverse as Metallica, Living Colour and Primus have all cited Rush as an influence, and Lee notes with satisfaction that whereas Rush was definitely a male headbanger's band when it first began, "I look out into the audience now and see more and more women, which is really nice."

There are also lots of fans now who weren't even born when Rush first began.

The album Roll The Bones finds Peart in top lyrical form, with tautly written songs revolving around the theme of how so much that happens in life seems to involve luck - a roll of the dice, in other words.

Peart is firmly of the belief that good luck only follows hard work, a point that he stresses in his lyrics.

"There are no failures of talent, only failures of character," he says, reciting a quotation whose author he's tried in vain to hunt down for 10 years.

But Rush has enjoyed incredible good luck, say both Peart and Lee, especially in having loyal fans who have stayed with the band along its many musical paths, beginning from the time when Rush used to play Toronto high school dances to its current stadium-sized lights 'n' lasers extravaganzas.

"People say we're the soundtrack of their lives, and I really like that," Peart says.

"They say we have changed and grown as they have, and they're out in the world doing professional and ambitious things. We still remain relevant to them, and that's perhaps the highest compliment of all."