Confessions Of A Rush Fan

Bob Mack Justifies His Love For Canada's Prog-Rock Pariahs

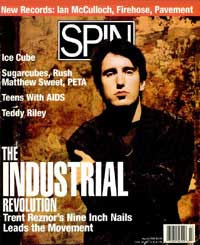

Spin, March 1992

Rush?

Yes, Rush. Not the movie or the B.A.D. II song. Certainly not "Rush Rush" by Paula Abdul or "Rush Street" by Richard Marx. And not even Frank Marino and Mahogany Rush. Just plain ol' eternally unfashionable, the-guy-with-a-high-voice-singing-scary-songs Rush.

So what in God's name is it doing in SPIN, a publication nominally devoted to alternative music? Well, I could go on about how Rush really is an alternative for lots of suburban loners, at least in the context of classic-rock overkill. About how it is the ultimate punk band for people who thought punk was bogus. But basically the bottom line is this: Even though you may think Rush is uncool, it's influenced a lot of the bands and artists that you probably think are cool.

Not the old fogies like Randy Newman, Nick Lowe, and Billy Joel (who apologized to Geddy Lee for missing the band's L.A. shows a few years ago). And not the cheeseball metal dudes like Queensryche who, for example, now employ Rush's former producer, lighting director, and video director. We're talking about some of the more critically praised and commercially successful groups of our era.

It all started a couple of years ago at the same L.A. shows that Billy Joel missed. Vernon Reid of Living Colour told Neil Peart that Rush had shown him that "a band could make it the way they wanted to." Peart was profoundly flattered because, he recalls, "I was so worried five years ago that we wouldn't leave any mark, that it was all for nothing."

Pretty soon anybody who played smart hard rock was being compared to the Canadian power trio: Metallica, Voivod, King's X, Faith No More, Jane's Addiction, Fishbone, Primus (Rush's current opening act), and even Guns N' Roses. Hip cartoonists Los Bros Hernandez created a kid drummer in Love And Rockets who wore a NEIL PEART IS RAD T-shirt; alt-rock goddess Kim Deal of the Pixies often wears her Rush tour T-shirt on stage. Flea of the Red Hot Chili Peppers even got his start in a band called Anthym (probably taking its "y" from the first name of Ayn Rand, individualist author of Anthem, which became the title of a 1974 Rush song).

While it's almost understandable that fellow musicians have come to give drummer-lyricist Peart, bassist-vocalist-keyboardist Lee, and guitarist Alex Lifeson their due, it's nothing short of a miracle that the critics are starting to come around, too. When I wrote my first defense of Rush for Village Voice in 1985, I was responding to colleague Chuck Eddy's slurs on the band. By the decade's end, Eddy had come around, calling it "the secret rock critic influence of 1989-90" and adding Sinead O'Connor, Midnight Oil, and Megadeth to the list of disciples.

And yet, if 1991 was the year that Rush returned with an album, Roll The Bones, that entered the Billboard chart at No.3, tour dates that sold out during a depression, and an updated sound that included a rap that wasn't half as goofy as Michael Jackson's or Michael Stipe's, I still couldn't help feeling a bit ambivalent . . .

"Neil, I hope you realize that your face is dangerously close to a pair of Damn Yankees promotional panties," I say.

Neil Peart, who is sitting in my sparsely-furnished apartment, laughs and launches into a good-natured anecdote about the band. In addition to ambivalence, I feel guilty about how lucky I am to have the lanky drummer over to my pad. Rush fanatics would give their eyeteeth to me in my sitch, and there I was trying to play it cool. It is the night off between the band's two shows at Madison Square Garden last December. Nursing a cold, Peart is nonetheless in good humor, especially while imitating a typical girlfriend at a Rush show. "Sometimes, you see this [exaggeratedly feigns sleep]. Sometimes this [tugs on sleeve]. But the other day Geddy and I saw this one girl literally hitting this guy."

With this in mind, I take the cutest young intern I can find at our office to the next night's show. She enjoys but doesn't love it and is amazed at how "well-behaved" the audience is. She is, however, impressed by how "real" Peart is when we meet him backstage. The only celebs present are John McEnroe and Tatum O'Neil. O'Neil says, "I really liked your drum solo" to Peart, who smiles and mumbles some pleasantries while I whisper, "Excuse me, but I've got to go call the gossip columnist at the New York Post." He hits me.

After spending the entire day in his hotel room reading the Sunday Times, Peart orders two glasses of dry sherry, tells me how he's practicing to records recorded by a Brazillian drummer named Milton Banana these days, and puts on Maceo Parker's 11-minute instrumental version of "It's A Man's World", retitled "Children's World."

Peart is seen as the ogre of the group, and granted, Lifeson (his pastimes are golfing and Pearl Jam) and Lee (rotisserie baseball and Nat "King" Cole) are far less intense; but it's Peart who wanted to do the rap, and who is able to drop trendy names, like Massive Attack into the conversation. Even so, he's still Neil Peart, whose rugged individualism makes Metallica's James Hetfield seem like a Commie in comparison.

I had set out to really grill the guy, but from the outset he takes control of the conversation. First he lays down the premises: Peart believes in "standards of quality" and "progress, though not linear"; for the most part, "there are no failures of talent, only failures of character"; it's also true that "first we must acquire the virtues and then eliminate the vices." He then quotes Duke Ellington's dictum that "there are only two types of music -- good and bad."

Eventually, though, we get more specific. Talking about the situation in Eastern Europe, the man who wrote "Free Will" concedes, "If I had been born in Bulgaria, no matter how much free will I'd have wished to apply, it would've been worthless." It is this hopelessness, which Peart also finds in the AIDS situation, that fills him with enormous resentment. "My response is always anger. It's so gratuitous. There's no reason, no fault, no blame."

I wondered if this cosmic capriciousness frustrated his white, Western, male, middle-class, and middle-brow nature. "The basic questions I ask in Roll The Bones -- 'Why are we here?' 'Why does it happen?' -- are the wrong questions. It's 'What can we do about it?'"

The Maceo jam climaxes, and I tell Peart that when I saw the sax master recently in concert he said that funk was "happy music." In those terms, where does he see Rush's music fitting in?

"At it's best, it's inspiring. Who's that guy in Seattle that pitched a no-hitter? He'd played his drums that day and when he was out there pitching, he was thinking of Rush songs. When I was writing 'The Pass' [a 1989 song about teen suicide], some kids told me that people who are truly suicidal listen to Pink Floyd. Rush is seen as hopeful music."

For the many who see Rush's music as hopeless, the pyrotechnic sticksman has a surprising tolerance. "It's fine for people to say they hate us -- our music is too busy, too self-absorbed elevated. Or they hate Geddy's voice. Fine. That's a taste thing."

Actually, it's more than a taste thing. After all, as the Duke would ask, "Is it good or is it bad?" At this point, Peart stops backpedaling and defends his honor. "Rhythm is the basis of a lot of musical styles. To Rush, it's just an element. That's why we're accused of being too busy, too convoluted, too far-reaching. Yes, we're restless, and yes, our work is uneven -- but no one can ever question the sincerity of the attempt."

No one was questioning the sincerity of the attempt, at least not in this room. I just wanted to know if Rush's '70s-style eclecticism was still relevant. Back in high school, it certainly had been. With its mix of power pop, barroom piano, and mock reggae, "The Spirit Of Radio" had been the prefect antidote to the skinny-tie ska geeks and anemic new wavers. But is the funk, folk, and rap of "Roll The Bones" just as effective in 1992? Peart, unflappable as ever, is free of doubt.

"'The Spirit Of Radio' is a valid musical gumbo, even now. The concept was to combine styles in a radical way to represent what radio should be. I think we really nailed that with 'Roll The Bones' as well. And it's happening on the fringe of pop music -- like Faith No More. They're not afraid to head off in a strange direction within a song. But it's still unacceptable in the mainstream. There's this strange intolerance among music fans."

Valid musical gumbo? I'd still buy that for a dollar.