The Godfathers of Cyber-Tech Go Organic

By Perry Stern, Network, November 1993, transcribed by Meg Jahnke

In the music business, like the animal kingdom, a process of natural selection occurs that weeds out the old and tired while making room for the young and strong. As a result, musicians have the shelf life of an open carton of milk on a summer sidewalk in New Mexico. Rock is still such a relatively new art form that we, the consumers, sit in stunned amazement as anniversaries roll by (Woodstock was 25 years ago? No way!), heroes wither (Mick Jagger is 50? Get outta town!) and embarrassing fads make a comeback (bellbottoms - 'nuff said). Because it's so geared to youth culture, rock has a tendency to discard sounds, instruments, technology and people with the casual thoughtlessness of a toddler and his toys.

In most artistic endeavors age is equated with growing, improving and wisdom. In rock, aging equals dying. That's why Rush is beyond rock. As the most enduring proponents of progressive rock, a field once crowded by now - (or ought-to-be-) defunct bands such as Yes, ELP, Genesis and Jethro Tull, it should be easy to dismiss our homeboy power trio as a staggering dinosaur too big and stupid to know it's among the walking wounded. But it's not. As the band's peers fade to grey, Rush explodes into technicolor. Rush is the metarocker of the future. It couldn't have happened any other way.

As far as the three members of Rush are concerned, it's not a new or improved or even old Rush that surfaces on their (can you believe it?) 19th album, Counterparts, but simply another Rush - a Rush for the '90s. Harkening back to an earlier, rock-oriented sound before the clutter of synthesizers and drum machines, Counterparts reveals a lean, mean Rush that has come down to earth after almost two decades worth of apocalyptic, epic compositions. Cynics might charge that the band is conforming to the latest MTV-era fad of "unplugging" its sound, although the words "acoustic" and "Rush" have yet to (and still shouldn't) be uttered in the same sentence. The group hasn't unplugged its guitars, just all those bloody keyboards. After years of assembling musical monuments to technology, Rush has slipped back down the evolutionary ladder a few rungs to make its most organic-sounding release to date.

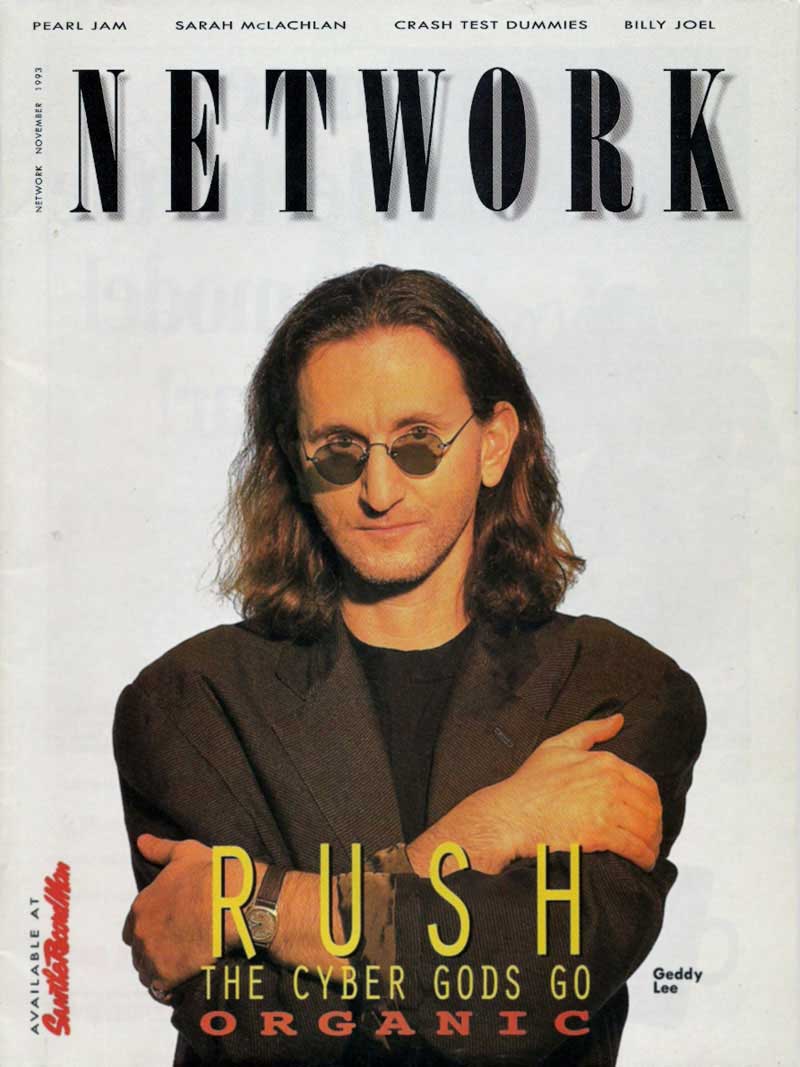

Sniffing into his handkerchief, a little red-eyed and ravaged by a late summer virus, bassist/vocalist Geddy Lee explains how the formerly distant, aloof Rush turned warm and fuzzy. "We've been moving in this direction over the last two or three records," he says, "slowly eliminating frills and trying to get a more rooted, more hard-hitting, basic sound." After years of pushing the outermost limits of the technological envelope, he asserts the new album is, in fact, "anti-technology."

"We feel like we drowned in it and now we're coming up for air," says Lee.

As befits an album made by adults (Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson turned 40 this year, drummer/lyricist Neil Peart is 41) Counterparts reveals a side of Rush that its members actively concealed for the better part of their career. There are love songs on the album, not the band's first, but certainly its most (oh, oh, here comes the "m" word) mature, most realistic love songs as well its most accessible commentaries on basic human nature. "I've been more comfortable with personal statements [and my] increasing ability to express them in non-cliche ways," lyricist/drummer Peart rather clinically declares over the phone from his home north of Toronto. "In 'Cold Fire' I have the woman speaking to the man and she's smarter than he is. It was a difficult technical challenge lyrically, but those are the kind of things that now, after all these years, you start to feel you have the craft to take on. I don't mind writing about love now, where I would have avoided that in the previous years just because of the inability to get beyond cliches."

Although the band blossomed in the '70s (with classics like Fly By Night, 2112 and Farewell To Kings) and flourished in the early '80s (Permanent Waves, Signals) Peart says, "the mid-'80s were difficult because music was moving so far away from our values. Musicianship suddenly didn't count. We had no respect from the critics and everyone else considered us kind of irrelevant." Everyone else but the loyal fan base that pretty well assured them platinum-plus sales and sold out concerts around the world.

Rush suffered an image problem. Hobbled by the perception that it exclusively wrote dungeons-and-dragons style epics or cyberpunk (before the word was coined) fantasies for nerdy 17-year-old boys, Rush found itself at odds with the way the music world classified it. "We were just as outside and experimental and idiosyncratic as Japan, Peter Gabriel or Brian Eno," Peart contends, almost defensively, "but certainly we never won that respect and were never perceived as having those intentions." This was a band that could have cleaned up selling pocket protectors along with its T-shirts at concerts.

But lately Rush can no longer claim to be the Rodnet Dangerfield of rock. If the "respect" illustrated by ticket and record sales wasn't quite enough for Lee, Peart and Lifeson, then two recent awards, given for vastly different reasons and by vastly different organizations, have helped assuage their moderately bruised egos. In early September the Arts Foundation of Greater Toronto announced that Rush would receive the 1993 Toronto Arts Award for Music for having brought "new standards to hard rock." Citing the band's sale of 30 millino records and six million concert tickets (including a record 22 dates at Maple Leaf Gardens) as an aside, jury head Denise Donlon (Director of Music Programming for Citytv/MuchMusic) says the award had more to do with the "international acclaim they've brought to the city," as well as the extraordinary generosity of their very "personal and very private" donations to local charities. Over the years the band has raised over $1 million for the United Way. "Beyond all the awards and statistics," the announcement stated, "Rush's music continues to excite, challenge and entertain."

The other award came in May from out of left field. With tongues placed partially in cheek, the members of the Harvard Lampoon (at 177 the world's oldest humor magazine) declared Rush the Musicians of the Millennium. At a black-tie reception in the mysterious Lampoon Mansion a secret ceremony was held inducting the three as honorary members, a distinction shared by such diverse luminaries as Winston Churchill, Bill Cosby, George Foreman and Robin Williams. The award isn't exactly a back-handed compliment by a bunch of elitists snickering behind their smiles at a band that takes itself too seriously. Steve Lookner, a former member of the executive board that chose Rush, explains, "They're very literate - one of the few bands that actually puts some humor into its lyrics and tries to make jokes once in a while. When there's a band that tries to be funny in an industry which doesn't have a lot of humor in it, we respect that."

"A sense of humor has kept the three of us together more than anything," Lee contends. "People attach this sense of severe seriousness to everything we do, but it's not like that. There's a lot of goofiness that goes into our material that's described as heaviness, which is kinda funny. And I guess there is a serious side to us, but it was a great relief to us to have the opportunity to go to the Lampoon and for them to recognize a lot of these stupid things we put in our songs. Here's this generation of young bright lights who will be making their way into comic writing and positions of leadership in the future and they got the jokes."

The "jokes" (as in older songs like "Superconductor" and "Red Lenses" that poke fun at pop icons and political perceptions) are few and far between on Counterparts, though. By shrinking the scope of his lyrics to personal rather than universal problems, Peart has verbally paralleled the down-sizing that Lee and Lifeson have accomplished sonically. But for both Lee and Peart what appears to be a simplification is, in fact, some of the hardest work they've done.

Where once it seemed all three players tried to fit as many notes or beats into a song as (in)humanly possible, now there seems to be a refinement of songwriting that resembles nothing less than conventional verse/chorus/verse three-minute pop song structure. "I guess the common word is 'retro,'" Lee says of Counterparts' sound, "but it's not, it's just simplified."

"That's the classic showbiz thing," Peart claims, "do a simple thing and make it look hard or do something hard and make it look simple. One is entertainment and the other is artistry."

"We've always written music to satisfy ourselves," Lee points out, "and we cross our fingers that there are enough people of similar sensibility that will appreciate our music. We don't have a target market, we just do what we do. Enough of our audience has stuck around and there's been enough interest among younger people that our audience is really 14 to 40. In some cities [the audience] is real young, in some there's even people my age!" he laughs. "It's pretty gratifying - we've turned into what the Grateful Dead are, for our kind of music. It's almost a cult thing."

But while Rush might be a "cult thing" elsewhere, it's about as close to a musical institution in this country as anything on this side of Gordon Lightfoot, Anne Murray and Don Messer's Jubilee. At one time the band might have been a guilty pleasure or an embarrassing footnote in some snob's music collection, but today Rush returns to the head of the class with a refined sound that puts bands half its age to shame.