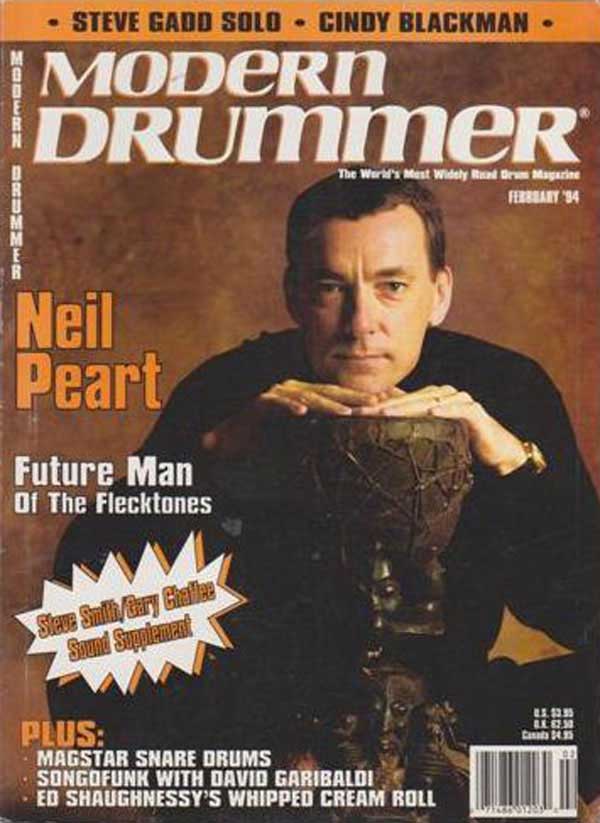

Neil Peart: In Search Of The Right Feel

By William F. Miller, Modern Drummer, February 1994

The Drum Master

Drumming has the power to unite people, no matter how varied their language or cultural background might be. On a recent trek through Africa, Neil Peart had a singular experience that proved just that. "I was in Gambia, walking through a small village, and I heard the sound of a drum. So of course I was curious! I looked into a compound and I could hear the drumming coming from a curtained room. I walked up to a woman doing laundry in front of the room. She could see my interest in the sound, so she waved me to go in. Inside I found a young, white missionary from a nearby Catholic school. Sitting across from him was the commanding presence of the local drum master. He was attempting to show the missionary how to play any kind of beat. The missionary was trying as hard as he could, but he wasn't having a lot of success."

After a time the drum master, frustrated by the missionary's lack of ability, noticed the other man who had come into the room. The master had no idea who this person was, but he thought to himself, "Why not see if he can play?" According to Peart, what happened next was fascinating. "The drum master gestured to me to try and play a rhythm. So we began playing together, and he started smiling because he could tell I had a rhythm - maybe not his rhythm, but a rhythm of some kind. We were playing and playing, building the intensity, and little kids started coming in, laughing at the white man playing drums. Then a few women came into the room, and everybody began dancing to our beat! The master and I even started trading fours. It wasn't a spoken thing, but he could tell that I would lay out and listen to what he was doing for a certain amount of time, and then he would do the same. It was just a magical moment." When they finished, a confused and startled missionary ran up to Peart and asked, "How can you do that?" Chuckling to himself, Neil politely responded, "I'm in the business."

World Inspiration

Neil's love of bicycling and travel is well known - it's almost the stuff of legend. While on tour with Rush he's been known to avoid the tour bus and bike to the next town and venue. When not on the road with Rush, he has taken his bike to the four corners of the globe, including Europe, mainland China, and Africa.

Upon entering Peart's Toronto home, one is immediately struck by the fact that this man has seen and experienced locales most people can't imagine. "Here's a prized possession of mine," he says proudly, showing a raw-metal sculpture standing about ten inches high and resembling a tribal version of Rodin's "The Thinker." "It's from Africa. It weighs about twenty pounds, and I had to carry it a hundred miles on my bike. but it was worth it." Neil's passion for authentic African art is obvious. Unique drums, with their rich, hand-carved elegance, are displayed in his home with reverence. Original Chinese gongs decorate a few of the walls. The decor hints at the fact that a drummer lives in the house, shouts at the fact that a word traveler resides there. Peart's love of travel is obvious, but does actually going to other parts of the world inspire him musically? "First of all, I think travel is very important for any person," he insists. "It's affected me enormously, and I'm sure it filters down to my work. Africa is not an abstraction to me anymore - neither is China. They're places I've experienced, places where I've met people, made friends - and just broadened my thinking.

"I've written lyrics that were directly influenced by my travels abroad. In a drumming sense, I've had some interesting experiences in different countries, experiences that may not directly affect the way I play drums, but that certainly inspire my feelings about drumming. And I've gotten very interested in hand drumming. Lately I've been working on playing the djembe."

One way Peart's wanderlust has directly affected the sound of his drums is through sampling. "One of the small drums I brought from China is an antique that's too fragile to play. So I took it and a few of the other delicate instruments that I own and sampled them - along with many of my other instruments like my temple blocks and glockenspiel. I've built up a huge library of sounds, and they've made their way onto our albums in many of the different patterns I play."

A particular pattern Neil has recorded that demonstrates the value of "world inspiration" comes from Rush's last album, Roll The Bones. "On that record we had a song called 'Heresy' that had a drum pattern I heard when I was in Togo. I was laying on a rooftop one night and heard two drummers playing in the next valley, and the rhythm stuck in my head. When we started working on the song I realized that beat would complement it well."

Premature Obituary

August 24, 1993, a day that will live in infamy - well, at least at the offices of Modern Drummer. It seems a radio station in Cleveland, Ohio made the announcement that Neil Peart was dying of colon cancer. For the rest of the day the telephones at MD rang off the hook from distressed Rush fans. How is Neil's health?

"You don't know how many times I've heard that rumor," Peart says, angrily. "Strangers have come up to me and asked, 'Is it true? Are you dying of cancer?' If it were true, imagine the insensitivity of someone asking you point blank if you're dying. Be that as it may, let me put an end to all of these rumors. I'm absolutely fine, and as far as I know I plan on living a long and happy life."

But why the rumors? It seems that, when Neil prepares for his trips abroad, he practically shaves his head for ease of maintenance. This presumably leads people to think he's having chemotherapy. "I think what also convinced people was that on our last tour I was wearing bandannas on my head," he says. "Even my daughter said I looked like a chemotherapy patient! But those bandannas did an excellent job keeping the sweat out of my eyes.

"It doesn't even take that, though," Neil continues. "I've been hearing these rumors for at least eight years. I came back from a bike tour of Europe, and my manager called me up and said, 'I just heard you were killed in an accident in Switzerland. I guess that isn't accurate.' There's no basis for any of this - it's absurd."

A Little Raw

For anyone who has heard the new Rush release, Counterparts, it's obvious that Neil, along with the rest of the band, is feeling very healthy. Counterparts is the heaviest Rush album in years. While there are moments of vintage Rush on the record, there's also a sense of further development by a band that prides itself on improving. According to Neil, "We try to stretch in several directions at once now. On our earlier records our learning curve was much steeper - we were changing and growing a lot. We seemed to concentrate on one thing at a time. We started with musicianship, then concentrated on songwriting, then on arranging, all as almost separate courses of a more organic, raw sound, and yet still have it be something that we would want to listen to," Neil explains. "It had to have a certain amount of refinement. By organic, we wanted to stress the nucleus of the band - guitar, bass, drums - and downplay the digital stuff, the sound processing and that sort of thing. As long-time listeners of music, I think we have pretty sophisticated tastes, so we weren't about to go in and make a thrash record. But we did want elements of that in our music."

According to Neil, the band had a carefully formulated plan. "We decided to use two different engineers, something we'd never done before. Normally we'd use an engineer for the entire process, right down to the final mixing. I always wondered why certain artists would bring in someone new, but we found that changing engineers really helped us get what we were after.

"We listened to literally dozens of engineers, knowing that we had to find the right guys if this plan of ours was going to work. To record the tracks, we chose Kevin 'Caveman' Shirley, whose work we enjoyed. He's known for raw guitar sounds as well as getting some very good drum sounds. When we interviewed him he had some very intriguing concepts, like putting bottom-end on the cymbals. And he was very concerned with mic' placement, as far as how it affects the drum sound, rather than just changing EQs or other board effects. He was determined to capture the natural sound of my drumset as accurately as possible. He didn't use any reverb. He wanted a purity of real sound, which was a unique way of working for us.

"The other engineer we used, Michael Letho, was brought in to mix the tracks," Neil continues. "His forte is mixing, and he constructed some beautiful mixes with instruments coming in and out, perfectly complementing each other. He brought a certain amount of refinement to the proceedings. If we had just used Michael, the record might have been too refined. Had we just used the Caveman, it would have been too raw. So we had the best combination of influences."

As well as their plan worked, there were some difficulties for the band with this new approach. "Using a minimal amount of reverb was hard for us," Neil says. "If the drums sounded a bit raw, we'd always just lay on that reverb and smooth everything out. Holding back on the reverb made this record a bit more difficult because the flaws were so apparent. If there was a 'bark' on the snare drum or a 'grunch' in a guitar note, it was obvious. But we kept them in right up to the final mixing stages.

"I also tended to listen to this record throughout the making of it much less than I normally would. With previous record we refined them as we went along. We would use one engineer and he would do rough mixes as the recording went along. When we'd hear those rough mixes along the way, they'd sound really good - almost like a record. Well, this time it didn't."

The Prize Drum

As for the drum sound on Counterparts, Neil made the decision not to vary it as radically as on prior albums. On 1989's Presto, for instance, Neil used a wide array of snare drums. "I didn't alter things as much for this record. I was quite satisfied with the up-front sound we were getting." Upon listening to the record one will immediately notice that Neil's snare sound is a bit lower-pitched than on the last several Rush releases. "I used some different snare drums, but for the majority of the record I used my Solid Percussion deep-shelled drum. In the past I used their piccolo drum, and of course my old standard Slingerland.

"I still have my arsenal of snare drums, but I didn't feel the need to use them all," Neil continues. "My prize drum is an old Rogers Dyna-sonic. It was my dream drum when I was a kid, so I had to have one! When I was fourteen or fifteen years old, a drummer using a Rogers Dyna-sonic snare had more impact on me than if he had two Rolls-Royces! Every time I look at that drum it gives me a spark of joy - but I just never use it. My favorite 'working' drum is still my old Slingerland. I've had it for years and it's never let me down. I thought when I got the Solid drum it would replace the Slingerland, but the Slingerland drum is just so versatile. That drum is a wonder - it's sensitive and aggressive." "My main attitude for this record was, I want the drums to sound like my drums," Neil says. "I didn't want the engineer to process them into something else. What I like them to do is take my sound and change the atmosphere around my drums to better help the sound work within a given composition. On a less aggressive song the engineer may smooth out the edges of my sound, adding a bit of 'air' to the track. On an aggressive number, the engineer will leave it raw. It's still my sound - my signature - yet it works within the given song more effectively. I like that approach because the differences are subtle."

Dangerous Waters

If you've ever attended a Rush concert you've undoubtedly seen many audience members "air-drumming" along with Neil. It can be an odd sight, especially when it's apparent that these fans know his playing note-for-note, right down to the fills. Neil's thoughts on his highly scripted drum parts may be changing. "I'm always listening to tapes of shows on the road so I know what's working and what sections need attention. I noticed on the last tour that, for the first time, the tapes were really a pleasure to listen to. I don't want you to think the tapes were flawless, but the quality of the performance seemed to be on a very listenable level. Our goal has always been to be able to accurately reproduce our studio work live. After so many years we finally started to realize that we can do it. It sounds small, but for us it was a big achievement.

"That realization gave us a lot of confidence to change arrangements live - stretching out songs and being more spontaneous in our performances. We were excited to be at a point where we felt we could have the best of both worlds: to be able to control our organized sections as well as have the confidence to stretch. There's no sense saying that music should be only orchestrated or only spontaneous. The only thing with spontaneity is that it tends to be less reliable!

"I remember talking to Mickey Hart during our last tour," Neil continues. "I had written to him after having read his excellent book, Drumming On The Edge Of Magic. So he gave me a call and that's how we hooked up. Seeing the Grateful Dead was impressive, realizing just how much improvisation goes on at their shows. Mickey told me that some nights a Dead show is dull; the improvisational thing just won't get going. Yet on other nights it's just magical. It's a risk that the band takes every night, and their audience takes that chance too. I respect the band for having the courage to do that.

"I've been pushing myself into those more dangerous, improvisational waters," says Neil. "It's both a quality and a flaw in my character that I prepare to death! I love rehearsing and getting better and better. I enjoy the process. Before we record an album I learn the new songs inside out, refining every little detail. And that's why I continued to play the exact same parts live as I recorded, because I spent so much time getting every element right. In Tim Alexander's Modern Drummer cover story [September '93 issue] he mentioned that he had never noticed that about me until Primus went on the road with us and he could see me perform every night. I'm glad to be able to play a song like 'Tom Sawyer' the same night after night, because it's so damn hard to play!

"With out newer material, though, I recognize that I don't like it sounding over-rehearsed. So in preparing to record the songs, I started leaving gaps in certain transitions or sections. I wouldn't let myself finalize a part, even up to the point when I would be recording the song. And that certainly added to the pressure for me. Then when I actually recorded a part and played what may have even been a mistake, with closer examination that mistake may have ended up bringing something magical to the track. Then I have to learn the mistake so I'll be able to play it live! But little by little that attitude of opening things up is coming into our music."

Finding The Right Feel

Counterparts is another solid showing for Neil's drumming. His drum parts consistently balance more standard beats with totally original patterns. Neil has a general approach: "When constructing drum parts I have to be sensitive to the songs, of course. I don't just play what satisfies me. You'll never hear me making noise under a vocal part. There's a certain level of respect you have to have. But on the other hand, when it comes to a guitar solo section, for example, to us that section isn't a guitar solo, it's a and solo. So all of us construct it as our own part. From an arrangement perspective those sections are free game. As long as what we're doing works and helps the track more exciting, it's acceptable.

"Finding the right feel for different parts of a song is always a challenge for me, because I hate to repeat things," Neil explains. "There are certain fundamental rock rhythms that at times work and need to be played and repeated, and I don't mind playing them. The same is true for a standard approach to playing a fill - going from snare to tom, for instance. To me they're like using the words 'so' and 'and': They're the articles of the language and to me there's no shame in using them. On the other hand I do want to explore fresh areas. I like to weld influences together to come up with something new. I don't pretend to think I'm inventing originality, but I'm hoping to create something original by combining previously disparate influences.

"For the opening track, 'Animate,' for instance, I used a basic R&B rhythm that I played back in my early days, coupled with that hypnotic effect that a lot of the British bands of the turn of the 90's had - bands like Curve and Lush. The middle section of the tune is the result of the impact African music has had on me, although it wasn't a specific African rhythm. I hear a section of a tune, and immediately I have to make choices, and many times those world influences I talked about earlier will come into play and contribute to my parts.

"Other songs on the record required me to find fresh ways to approach familiar, time-honored drum parts," Neil continues. "I think the nature of the songs on this album brought out a lot of my R&B background, and I don't think that's an area I'm known for. But all the first bands I played in were blue-eyed soul bands. I played a lot of James Brown and Wilson Pickett tunes, because in the Toronto area that's what was popular at the time. All of us grew up playing 'In The Midnight Hour.'

"R&B is a part of my roots, and as a band I think we all played it and enjoyed it. But as we developed we drifted off into the other styles of the 60's, and when the British progressive bands came along we went in that direction.

"The instrumental track on this record, 'Leave That Thing Alone,' is built around R&B bass/drum interplay. But to make it original I had to change up parts. In the second verse I go into a Nigerian beat, like something you'd hear on a King Sunny Ade record. Later in the song I go into a quasi-jazz pattern, and all these things are introduced for our own entertainment as well as to make the piece more interesting.

"When I hear Geddy and Alex's demos the influences are sometimes very clear to me," Neil says. "And I think we're secure enough to directly use those influences. If Geddy and Alex bring in a tune that has a section that sounds like the Who's Live At Leeds, I'm definitely going to put on my Keith Moon hat and go with it." (Check out the extended fills before the guitar solo on "Between Sun And Moon," from Counterparts.) "If there's a song with a '90s grunge-rock section," Neil continues, "we're secure enough to go in that direction. All of these things are amusing to us, but they're also available to us to try and create something fresh from their inspiration."

A song like "Stick It Out" proved difficult for Neil because of its fairly simplistic riff. "How could I approach that song properly and yet give it a touch of elegance that I would want a riff-rock song to have? I don't want it to be the same type of thing you'd hear on rock radio. So I started bringing in Latin and fusion influences. There's a verse where I went for a Weather Report-type effect. I used some tricky turn-arounds in the ride cymbal pattern, where it goes from downbeat to upbeat accents-anything I could think of to make it my own. That song verges on parody for us, so we had to walk a careful line. We responded to the power of the riff, yet still found some ways to twist it to make it something more.

"'The Speed Of Love' is kind of mid-tempo, more sensitive rock song," Neil says. "That song probably took me the longest to find just the right elements I wanted to have in a drum part. What made it a challenge is that I wanted the feel and the transitions between sections to be just right. I played that song over and over, refining it until I was satisfied. I don't think a listener will hear all the work that went into that track."

Accident By Design

While Neil may turn to many outside influences to help him create within Rush, there are some elements in his playing that are definitely his own. Peart concurs: "I think I do have certain signature licks that I play. And I don't mind a certain amount of repetition if it is indeed something that is my own. I suppose it takes a bit of repetition to make it my own! It does become hard to pick these things up, though, because they tend to be subtle, at least to me.

"I think what happens is, you'll hear a certain drummer play a great beat or fill, and then you'll practice what you think you're hearing. Many times the result of that effort ends up being something that is completely your own. Even if you can duplicate the exact notes, in a different drummer's hands it just won't sound the same."

Neil feels that a lot of what he plays is a reflection of his personality. "I do like things to be organized," he admits. "If something is well-organized, it has the potential to be something special. I tend to approach life the same way. If I'm going on a trip somewhere, like the bush in Africa, you'd better believe I've spent a lot of time figuring out what to take so I'll be prepared. I might be organized, but at the same time that's hardly a safe circumstance. Organization is not necessarily a conservative thing."

Neil's approach to music is certainly similar. "When we go in to record, I spare no self-flagellation of playing the songs over and over again until I've got them. And it's the same thing before a tour: I spend weeks just rehearsing on my own before we start as a band. But I know it's time well spent because that work gives me the confidence to step of into the unknown with some foundation.

"When I went into the studio to record my parts for Counterparts, I was prepared," Neil insists. "That's why I could record all of my track in first and second takes. We put together and learned the material, we worked with [co-producer] Peter Collins refining the material, and then I practiced for another week to get totally comfortable with the songs and the changes to those songs. I recorded all of the drum tracks on this record in one day and two afternoons-that's all it took because I was prepared.

"My whole approach to life is accident by design," Neil says. "Every thing I do has to be that well-organized, or I'm not comfortable with it. But at the same time, within that frame of organization, I'm really comfortable with contingencies, because I'm prepared. It's an interesting thing because a lot of people say it's better to be spontaneous, to breeze through and let whatever happens happen. What I find with those people is that they're not prepared to take advantage of the opportunities when they occur."

The Ultimate Involvement

With so many years of intense drumming behind him, you might that a certain amount of burnout might have set in on Neil. Quite the contrary. He still seems earnest about his deep feeling for drumming. "There are certain things about my playing that are just an honest reflection of me. I couldn't stop playing hard physically, because I love physical exertion in so many other areas of my life. And that actually came from drumming, because it was my first physical endeavor-my first sport, if you like. Before it I had never been involved in anything athletic. Drumming gave me the stamina to get interested in cycling, cross-country skiing, and long-distance swimming. So that comes out of my drumming naturally.

"I've had this fleeting thought over the last year or so, trying to think of any other human activity that so much uses everything you've got physically and mentally. For me, playing drums is the ultimate involvement. It's as involving to an athletic degree as a marathon run is, but at the same time your mind is as busy as an engineer's is, with all the calculations a drummer has to make.

"I have a quote from a NASA director who was a friend of ours," Neil continues. "He came to see us play, and afterwards he made the comment that I'm obviously using a great deal of mental energy. He thought it was funny that I would expend so much mental energy on playing drums-he said it with a certain amount of disdain-but that's what it takes! When you apply the standards I've described to drumming, it does become the ultimate expression both mentally and physically.

Peart On Congas?

If you've followed Neil's career, you've seen his kit evolve. Over the last few years he's done away with his second bass drum (opting for a double pedal), added a floor tom on the left side, and changed his overall tom positioning. For the new album, though, Neil did not alter his kit. "By adding the floor tom on the left and shifting my tom sizes down, which is what I did for the last record, that gave me a lot of possibilities. I think that change gave me a whole new starting point and made a lot of my fills just sound different. It drove me to change a lot of preconceptions about the fills and patterns I play. I think I'm still exploring it."

Neil did have a specific idea he wanted to try: "I thought of a radical idea for a kit that came about do to the interest I've developed in hand drums, which I really began exploring during our last tour. After staring at a computer keyboard for long periods of time, there's nothing better than sitting down and playing congas. It's a great release. So I came up with a setup where I could play congas and bongos with my hands, yet still trigger bass drum and snare drum sounds with my feet. I've been using my feet to trigger kick and snare sounds for a few years now on certain songs in our set. So I thought the concept was a little radical, but still very interesting and very possible. but there was one problem: The songs didn't really call for any bongo or conga parts! I was set up for a stylistic shift and prepared and interested to make it, but in fact didn't have a place for it. Maybe I'll be able to apply it next time."

What inspired him to get into hand drumming? According to Neil, "During our last tour, Primus was opening for us, and Herb Alexander and I would have jams in the tune-up room before the show. He had a PureCussion drumset in there, and I had some hand drums. We'd be jamming, and members of their band and our band would drift in and out of the room and join us in making some impromptu music. For the most part people would be using instruments that they don't normally play. Someone would pick up an accordion, and someone else would pick up a flute-that was primo! Somebody would be playing bass, and somebody would be playing on anything we could find to hit.

"We had some great jams with just found sounds," Neil continues. "I remember one in particular where I was playing a beautiful pattern on a bicycle frame against Herb's drumming on a garbage can, and it was happening! In Berlin, we had dressing rooms that were just little outdoor trailers. There were all sorts of metal grids from the arena stacked outside. We set up in this little shed-it was raining outside-and both bands were just jamming on found percussion and a few other instruments. It was a great escape from the day, and a good musical exploration."

Neil Also Waltzes

The backstage jam sessions also led Neil to new areas in his drumming. "At a later point during the tour, Primus were gone and we were out with Mr. Big. So I went out and got a PureCussion set for myself, because I really enjoyed Herb's. I set myself a course of study. It was getting near the end of the tour; you'd think I'd not want to even be thinking about playing drums. In fact, I found that playing something different was the cure for the usual boredom that sets in. I'd go into the tune-up room and play Max Roach's 'The Drum Also Waltzes.' It was such a good exercise for me, and it was so different from what I was playing on stage."

Neil also received some hints from Pat Torpey, the drummer with Mr. Big. "Pat's an accomplished drummer with a background in some areas of drumming that I'm not familiar with-Latin, for instance. He showed me some great patterns to practice. And I was just exploring any possibility I could come up with. I'd play an ostinato pattern and then try to get my other limbs to work over the top of it. It was an ideal activity for me to be doing before a show. It kept my drumming alive for me during the last part of the tour, when normally I'm feeling like I've been out for too long."

Rich Vs. Peart

The drumming community witnessed a rare event a couple of years ago when Neil Peart agreed to headline the Buddy Rich Memorial Concert, held in New York. Neil, who avoids performing clinics, made the exception due to the fact that his involvement would help provide a college scholarship for a needy drummer. But what was it like to go from a three-piece rock group to a sixteen-piece big band? According to Neil, "It was a major, major challenge. I vacillated a lot about accepting it, and I wished I had an excuse not to! I wished I could have said, 'Sorry, I'm going to be in Finland that day.' All kidding aside, I realized that year that I had been playing drums for twenty-five years, so I felt I should do it for myself to mark the occasion.

"I got the video of the first Buddy Rich Memorial concert, and I was just so impressed at how well everyone played...I had enormous self-doubt after seeing it," Neil admits. "But then I got inspired and thought, I'll do it like Buddy would have done it! I realized that all the other drummers essentially just 'did themselves,' as opposed to trying to play in a similar style to Buddy. I tried to learn what Buddy played on the songs I was going to be performing, exactly as he played them. I wanted to honor him by playing as much like him as I could. I even tried to figure out the stickings he used, as much as possible. I felt safe, in a way, following his example into what were unknown musical waters for me. It was such a challenge because I had to try and get into his mind. Wandering around inside Buddy's conception of things was amazing. To see how he would set up a fill and execute it, and even how he would view an entire arrangement, was very rewarding research for me."

Unfortunately for Neil, the evening wasn't as successful as he had hoped. "I did have a few problems with the event. I was the last drummer to rehearse with the band on the rehearsal day, and since it was late in the day a few of the guys in the band had to leave to play gigs. Steve Marcus, Buddy's long-time tenor sax player, had to leave. The pianist had to leave early, so that was a drag. The Basie and Ellington songs I performed were both founded on piano/bass/drums trio, and to not be able to fully rehearse with the piano made it difficult. The setup on the day of the concert wasn't well-planned, either. I was far away from the band, and it was very tough for me to hear them. The horns were inaudible to me! when I watch the video of my performance I can see myself straining to hear them. It's hard to play under those conditions.

"The performance came off okay, but I just didn't enjoy it. The next day I had a long drive from New York to Toronto, and the drive was the perfect therapy for my disappointment. I really got to think about it, and I got re-inspired to try it again. I want to be able to enjoy it and do the kind of job I know I can do. I hope to perform with the band again."

The Future Of Drumming

Rush has been around a long time. They've influenced a host of bands, some of which are almost direct descendants-groups like Primus, Queensryche, Dream Theater, Fates Warning. They all name Rush as a major influence. But does Neil feel as if he's passing the torch to these new bands? "On reflection, yes, I do think that passsing the torch is an accurate metaphor. I had a lot of reflections over the last couple of years about the nature of heroism, what a 'role model' is supposed to be, and the differences between the two. That thought manifested itself in a song on the new album called 'Nobody's Hero.' A role model is obviously a very positive example of what can be accomplished, and it's what I think, with all humility and pride, Rush has been-a good role model for other bands. We've done things the way we think they should have been done: on our terms, making all our decisions based on that and not on the market or what the record company told us we should do."

As for his own place in drumming history, Neil is quite humble. "I suppose I've set an example as a busy drummer: a guy who has played a lot of different parts over the years-and has still been able to make a living," Neil says jokingly. "But this brings me to an interesting point. A few years back drummers were being shoved down further and further in the creative process. I was really wondering what was happening to all of the young drummers. At that point most everything you heard on the radio had drum machines. the drummers you heard were just keeping a beat. It was considered very uncool to play drum fills-and God help you if you did a drum solo! In the '80s there was no place for a drummer to play. I was very concerned about the future of drumming.

"We got to the '90s," Neil continues, "and suddenly all sorts of bands came up with drummers who are playing. The recent bands coming out of Seattle and from across the States are revealing some fantastic drummers. Somehow, the torch was passed. These drummers were practicing and improving throughout the '80s, preparing for the time when they'd get the chance. I honestly feel this is a very exciting time for drumming. It's so gratifying to hear it come back, and come back with such a vengeance. Just a few of the newer guys I've been enjoying include Dave Abbruzzese of Pearl Jam, Matt Cameron from Soundgarden and Temple Of The Dog-I love his playing-and Chad Gracey from the band Live, who plays just what you want to hear."

It would seem that Neil Peart is now secure with the state of drumming. At this point no one can deny his contribution. "If nothing else, I did consider myself a champion of drumming as an art form. The people who I held up and admired from the past had always approached it that way, right from the first players I ever heard-Gene Krupa and Buddy Rish. I always championed the values of musicianship and of drummers who could actually play. all of that mattered to me and always will. A few years back it seemed as if those things didn't matter anymore, and I felt undercut and genuinely worried. But with this new generation of drummers coming up, I can breathe a huge sigh of relief. Everything's all right!"