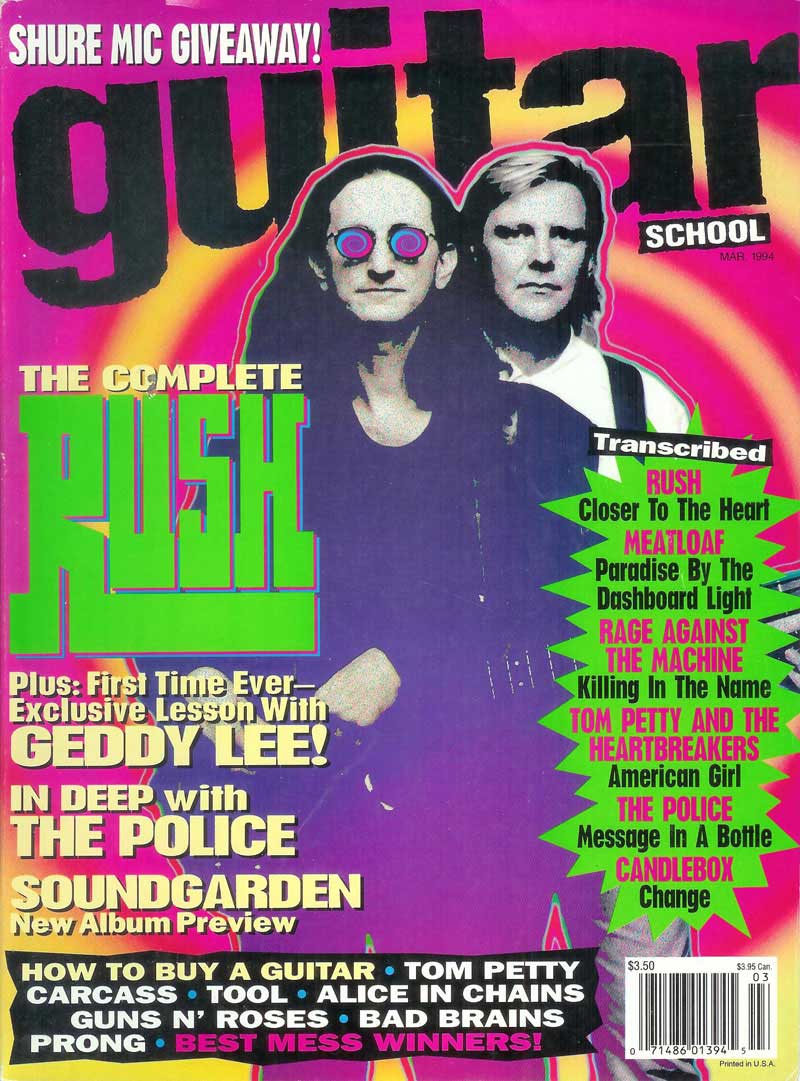

Back To The Future

Alex Lifeson And Geddy Lee Return To Their Roots With COUNTERPARTS, Rush's Nineteenth Album

By Matt Resnicoff, Guitar School, March 1994, transcribed by pwrwindows

Even if the "progressive" tag no longer hangs on Rush as easily as it once did in the '70s, the word is still an accurate description of the band's attitude towards creating music: Geddy Lee has no problem juggling two or three instruments in the course of a single song, Alex Lifeson spends days on end communing with his guitar in his subterranean digital studio, and drum guru Neil Peart memorizes hours of blindingly complex parts, and then records them flawlessly, usually in one or two takes.

With so much input shaping each project, it's not hard to imagine why the bond has taken some measurable changes in direction. "We decided the guitar should really come up and lead again," laughs Lifeson. "It feels like Geddy a Neil are standing in front of Neil's drums, the way we used to do. We wanted to make Rush like it used to be, when we didn't have to think as much."

Counterparts, the group's nineteenth album, reveals as much about Lee and Lifeson's compositional growth as about lyricist Peart's state of existential and polyrhythmic turmoil. The focus is back on Rush as a power trio; parts that several years ago would have been played by Geddy's keyboards are now firmly back in Lifeson's domain. And new tunes like "Cold Fire" and "Between Sun & Moon" enjoy a Marshall-stack nastiness that comes closer to sneering at the highly processed guitar tones reminiscent of Rush's most recent albums. The bass lines are as melodic and aggressive as ever, and as Lee continues to develop facility in what he calls "slapping without slapping," the bottom end of rock's most enduring trio moves into its most groove-oriented position yet.

But have all these changes affected the bands ability to play its old songs? "They come back pretty quick," Lee chuckles. "But the first couple of days are usually hilarious. You think you know a song, but you start playing it, and it sounds terrible. The first day of rehearsal we sound like a lame garage band trying to play Rush songs. After a couple of days we start sounding like a Rush clone band, and then in the second week or so we start sounding like us."

GUITAR SCHOOL: It's interesting that in the '80s, when rock guitar was evolving toward new standards in soloing, Rush went in the other direction and Alex played more texturally.

GEDDY LEE: Alex loves gadgets. He's a scientist, this guy [laughs] I can understand that, because some of these devices create a whole dreamy background; it feels like you're being accompanied without being accompanied, and that gives many guitar players confidence. Alex is such a good player, and there was a period when all that stuff was great because it was fresh and new. But I think he got a little dependent on it, and some of it actually clouded up his brilliant guitar playing.

ALEX LIFESON: There was certainly a competition between the guitar and keyboards on those albums. A couple of times, out of scheduling necessity, keyboards were laid down before guitars and overwhelmed the recording. We actually had to thin out the original keyboards for Power Windows and Hold Your Fire! We got off on layering them, but it became difficult to fit the guitar in. There was something fundamentally wrong with that concept of this band. I know I've been a catalyst to move away from records like that.

LEE: Well, we like to let Alex think that. [laughs] Realistically, our writing has just been getting more streamlined. Also, there were tracks on previous records that we felt should be more powerful. That point was really driven home when we listened to our live versions: they had a heavier attitude we hadn't captured on record.

Engineers would say to Alex, "If you want this sound to be in your face, you've got to bypass these effects." But Alex has a very complex mind. He wouldn't compromise the unique sound he'd developed. The new approach had to be proved to him, and to myself and Neil as well. So yes, he wanted to have his guitar more up front, but he always has wanted to have his guitar more up front.

GS: Geddy, how have you changed your bass playing to compliment this new approach?

LEE: The big change was realizing that as much as I liked the sound I was getting on the last records, our overall sound had gotten a little polite. I decided to go back to a more aggressive sound. When I look back on the way my sound has changed over the last ten years, I think I got bored every couple of records with the bass I was using. On this album, I went from pre-active electronics to my old [Fender] Jazz Bass. In the demo studio I go into a direct box, straight through a Palmer speaker simulator; that combination gives me a pretty aggressive sound. When we got to the studio, I was going to use Trace Elliot amps, but one of the assistants had an old Ampeg head he had literally pulled out of the garbage and repaired, so we drove the Trace Elliot cabinets with that. It was completely overdriven, almost to the exploding point, but we got a great sound. So we'd use a balance; some songs we'd only use the amps, some songs we'd only use the direct box combination.

Another part of the reason my sound had gotten polite was light strings - that and the Wal, which is a very clean-sounding bass. So I thought, "I'll go completely in the other direction. I'll use a Jazz Bass and heavier strings and get a more substantial bottom end." I'll still use the Wal live, and the Jazz. And I was given a Palladium bass by Jeff Berlin, which he designed. It's gorgeous. Jeff set up the neck for me and did an amazing job. It's like butter.

GS: Alex, was your outlook affected by touring with Eric Johnson, Steve Morse and Primus' Larry LaLonde?

LIFESON: I admire Eric and Steve on a personal level. I get stimulated by what they do, not like "How can I play what he played"?" but, "How can I play what I play a little differently'?"

Steve was always playing. I normally put the guitar down for a few months after finishing a record or tour. He made me feel guilty. I asked Eric recently, "Do you ever put your guitar down for more than a day or two'?" He said, "Man, alter we finish a tour, I won't play for a month." I felt like, [clenches fists] "Yes! Excellent!"

To me, Larry's a genius. The stuff he plays is off the wall, but he plays it every night, and I really got off on how he thought about it. You should hear him play the clarinet.

GS: What would you say are your bandmate's strengths as players?

LIFESON: Geddy has fantastic rhythmic sensibilities. He's so tuned into Neil - even during soundcheck jams, they would start playing something I'd never heard, and they'd be so locked in. They wouldn't even be looking at each other and they'd know where things were going. Geddy is very, very tight in the rhythm section. Stylistically, he's unique and it's great that his sound has become more aggressive.

LEE: Alex's great strengths are his ingenious chord structures. He's very underrated because so much of what he does is one guitarist playing a two guitarists' role. On record it sounds like two guitar players overdubbing. I don't know if there's anybody on the planet who can play arpeggios as well as this guy; they're always so original and melodically interesting. And they're quite internal, so you have to really listen to appreciate the complexity.

GS: You guys are still toying with the rules: The new instrumental "Leave That Thing Alone" has a bass melody over a funky guitar pan, as opposed to the other way around.

LIFESON: Geddy had this little keyboard thing for the choruses, and I had this clean verse thing kicking around from the last tour. As the song developed, we thought, "This is cool, it's not a big stage for showing off like so many of our instrumentals" - it's a song that goes through many moods and creates very nice colors. The solo was from my original [Alesis] ADAT [a digital tape recorder] version: just a solo I threw on, but it fit. It has an almost Celtic flavor.

GS: Are instrumentals still essential to Rush? Do you consider them indulgences, or something that is expected of you?

LEE: All those things. They are indulgences, but they are also, in some ways, our most natural state. They're the easiest things to write and the most joyful things to play. It's our reward. It's like, "If you get through all these eight songs, there's a little instrumental waiting for you at the end." So it's a way of answering the incredible amount of restraint and "taste" you have to have when you craft a four-and-a-half-minute song; when you get to the instrumental you can throw all that out and really enjoy yourself.

LIFESON: And they are spontaneous. That's the thing I love about instrumentals. We throw them down, then we give them to Neil and he figures out drum parts.

GS: Alex, are you still in love with Telecasters for the studio?

LIFESON: I find it very valuable when you layer Telecasters with other guitars. The combination I used for this record was a Paul Reed Smith, a Les Paul and a Tele. I combined the three to come up with one fat sound. I'll usually lay down the Paul Reed Smith first because I find it the most comfortable, and it has the smoothest sound - a really nice low end, very nice mids, and the high end isn't too shrill. Then I add the Les Paul to get thicker, lower mids; and the Tele brightens it all up.

GS: Is it tough to match up the parts cleanly when you use such a present sound?

LIFESON: Well, I've had a lot of practice. [laughs] I've already done it five times before I put it on record. I layer way more guitars on my ADAT than on the records, so I've already gone through the nuances. In the past I was very anal - it had to be dead, dead in, but over the last couple of records I've realized there's no mileage to gain from that. You're better off going with whatever feels good.

GS: Does the PRS's eveness change your amp needs?

LIFESON: I'd been using the Gallien-Krueger MPL100 into twin Celestion-GK cabinets, and that worked for a few tours. For this record I used a [Peavey] 5150 and a Marshall stack; I also pulled out a [Roland] JC-120 for a couple of small things. The idea was to benefit from the tube front and back end. There's something about tubes that plugging any of those guitars into it is a step up. I also just got a DigiTech multi-effect unit with a tube preamp front end, so I can get a really nice sound and still have all the effects.

GS: Geddy, is your home studio as sophisticated as Alex's?

LEE: No. I have no interest in having a full-blown studio. I have a sound-proofed writing center where I have some basic equipment: a good monitoring system and a small computer setup that I can record into quickly. It's geared to be simple and to concentrate on ideas, as opposed to technology. I don't really want to be an engineer, I just want to get my ideas on tape.

GS: How do you feel working through your ideas in a home studio, away from the band?

LIFESON: I like working in there. The studio is in a sub-basement in my home, so I can crank it up without disturbing anyone in the house. Before we started this record I spent a month messing with ProTools and Cubase [music software], and I finished a couple of cassettes of ideas and fairly complete songs. It was nice to go into the writing stage with that material. When we finish this tour I'm going to have a big chunk of time, so I'm starting to toy with the idea of a solo project. The last few times I've committed myself to just messing around, I've liked the results. They're quite different from what we do in the band, which in the past wasn't the case.

GS: You have a very low-key, practical manner. Docs that help you focus?

LEE: For me it's a necessity. When I'm doing a Rush project, it's so intense and all-encompassing that I ignore other things in my life. The trick to being able to stay in a band for a long period of time is to have a balance between career and home life and intellectual pursuits. These are the things that make up a happy life - not just being obsessed with music 24-hours-a-day.

Bass Clinic: The Bottom Line

In this rare lesson, Rush's GEDDY LEE shares the secrets behind his classic bass lines as well as some of the most thunderous moments on the band's latest album, COUNTERPARTS.

AS THE BOTTOM END of one of rock's most celebrated power trios, Geddy Lee has elevated the role of the bass guitar to new heights. His distinctive sound, characterized by driving, single-note grooves; busy, melodic fills; percussive, Flamenco-like flourishes; and harmonically rich lines, has established Lee as one of progessive rock's greatest innovators. Geddy recently agreed to sit down with us, bass in hand, and talk about what makes his lines tick.

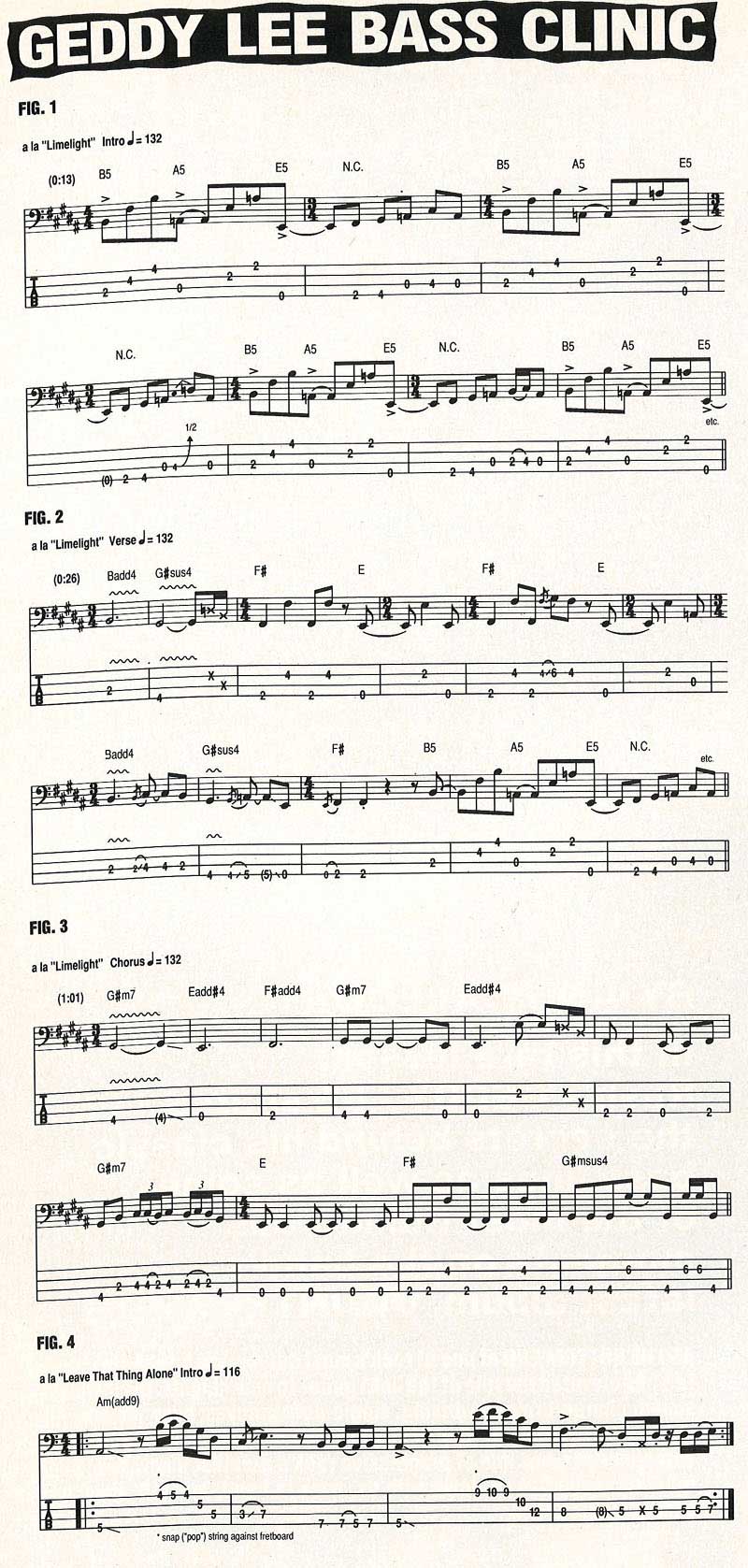

GUITAR SCHOOL: One of the heaviest, most recognizable bass parts in the Rush catalogue is the line from "Limelight." Part of its uniqueness stems from the persistent "three against four" feel during the intro and verse sections.

GEDDY LEE: The intro figure is a bar of 4/4 and a bar of 3/4, alternately. This is how I play the line now [see Fig. 1]; it has evolved a little over the years. And I play the riff in the 3/4 bar a little differently each time.

The second two-bar phrase of the verse [see Fig. 2, bars 3 and 4] goes from a bar of 4/4 to a bar of 2/4, which is the same number of beats as two bars of 3/4. I use octaves all throughout this section, as I do in the chorus [see Fig. 3], starting in bar 5, and in bars 9 and 10. I play the chorus a little differently now, too.

Some of the changes I've made have been unintentional, and I've funked up the chorus part a bit. I don't even know how I originally played it! Most of those performances [on record] from 14 years ago were "one-offs," anyway. Even during that year's tour, I didn't play the song exactly as it is on the record. Fourteen years later, songs mutate into something else. People don't realize how much of a record is made up of fortunate accidents, or spontaneous composition, like "Oh, he went to that cymbal there, so I'm gonna go with him." It's never a case of sitting down and writing it in stone.

GS: Are you against spending months, even a year, making an album, as you might unintentionally iron out some of those "accidents?"

LEE: I think there's a danger there, yeah. But it all depends on the type of music, and how much "life" it has. Some of the stuff that people spend three years on is really pop-oriented, so there's not much room for playing in the sense that we like to play. It's all craftsmanship to a particular goal, and that goal is creating music that will be digested over the radio in the right way. When putting a song together, you've got to be flexible; you have to look at the song and say, "What is this song all about?" If the song is driven by the lyrics, or the vocal melody, or a particular feel, our job as the rhythm section is to not smash that up. Your goal as a musician may be to playas much as you can, and make everything as difficult as you can for yourself-which is very much Neil's attitude [laughs]-but there are songs that you just shouldn't step all over. I guess that's where taste comes in. Sometimes I say to myself, "Ten years ago I would have stepped all over this song, but now I'll wait 'til the guy stops singing before I start doing my little thing." [laughs]

GS: Do you guys occasionally have disagreements about what constitutes "stepping on" a song?

LEE: It happens from time to time, but usually Neil and I are great at working out the rhythm section stuff together. Very often, that stuff is worked out after the song is structured on a demo so that we have the vocal, the chorus, and we know to a certain degree what the guitar is going to be doing. The rhythm section works its way around that.

I keep the bass very simple when I first write a song, so I can just pedal through it to show Neil the changes. It gives us a chance to look at the song in its simplest form. After that, it's easy to say, "How can we add a bit more funk to it?"

GS: Are songs ever born in the midst of a jam session?

LEE: Oh, yeah. That happens a lot. Alex and I record all our jams, and many times those happy moments, where we really start grooving, get dissected and transformed into songs.

GS: Is "YYZ" a song that came out of hammering out riffs in a jam?

LEE: Yeah, and the same is true of nearly all our instrumentals. Jamming is really a recess: "There's no vocal melody, there are no lyrics, WEEE-HA!" I think the instrumental on the new record, "Leave That Thing Alone," is the best thing we've ever written. Its intro goes like this ... [see Fig. 4]

GS: There's a lick in that tune that reminds me of Jethro Tull, from the old Glen Cornick days of Stand Up and Benefit.

LEE: Really? I love Tull. Thick As a Brick is my all-time favorite; it'd be at the top of my "desert island" list - Passion Play, too, which is not a very well-liked record, but I loved it!

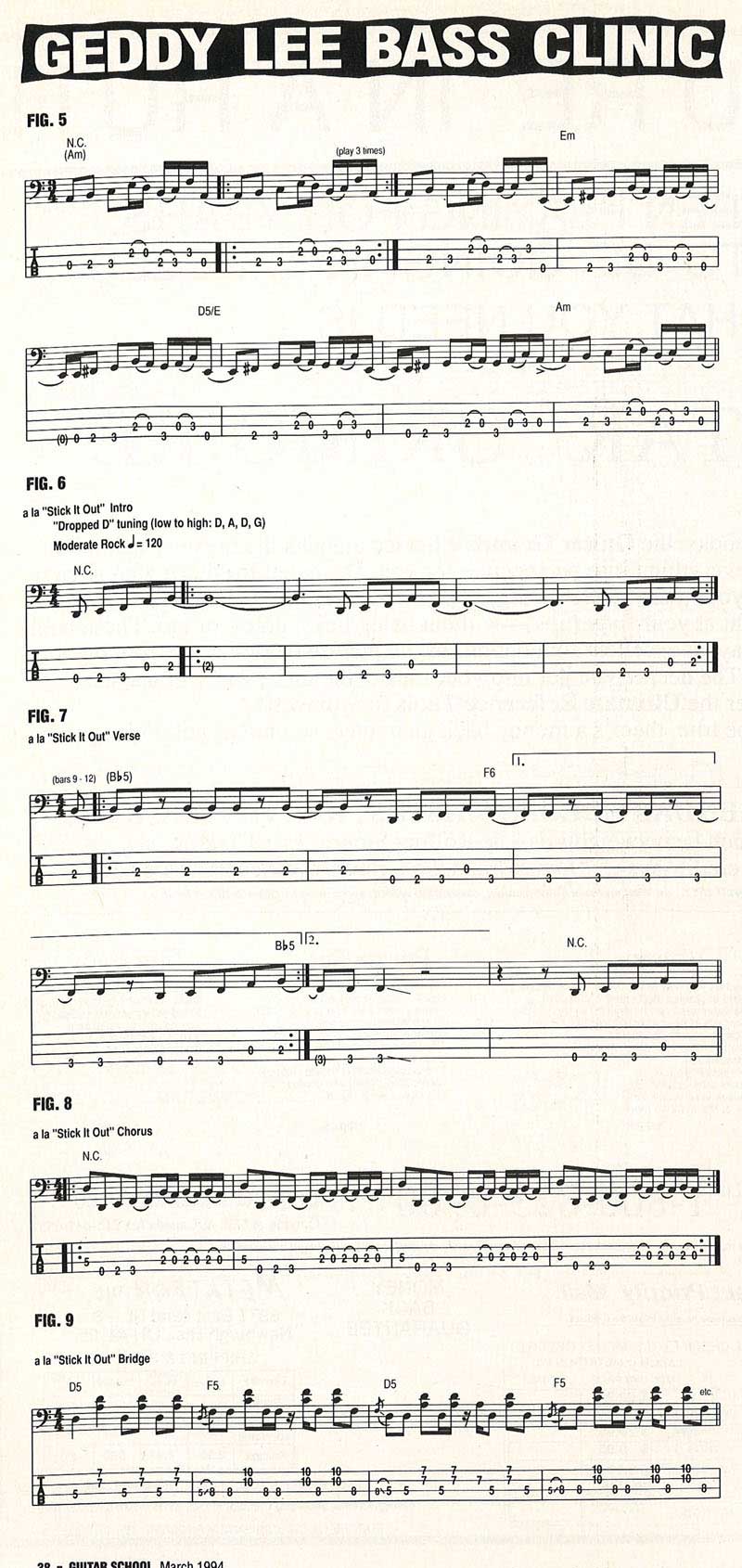

This is probably the line that reminds you of Glen Cornick. .. [see Fig. 5] It's in 3/4 too. The figure over Em [bars 6 and 7] is slightly different than the figure over Am.

GS: "Stick It Out" also sounds Tull-inspired, especially in the "Aqualung"-like opening lick.

LEE: You think so? I had the E string tuned down to D for that one. The intro is a little deceptive, rhythmically [see Fig. 6], because it's a little hard to tell where the downbeat is. The line becomes clearer in the verse section [see Fig. 7], after the drums establish time. Then the chorus "hook" riff follows ... [see Fig. 8]

The middle section is built on these chords [see Fig. 9, which illustrates root/fifth chords, is heard behind the lyric, "Each time we bathe our reactions ... "]. I'm already playing this a little differently on stage from the way it is on the record.

GS: On "Red Barchetta," there's a section following the first verse where the guitar plays a low F to low E repeated figure, over which the bass plays low A to low G, creating a weird, dissonant effect.

LEE: I know which part you mean. It's really demented. The two notes we're playing against each other are intentionally dissonant, and it's supposed to give you an upset stomach! [laughs] After we recorded it, we turned it up really loud, and the notes were vibrating against each other in a really nasty way. We loved it!

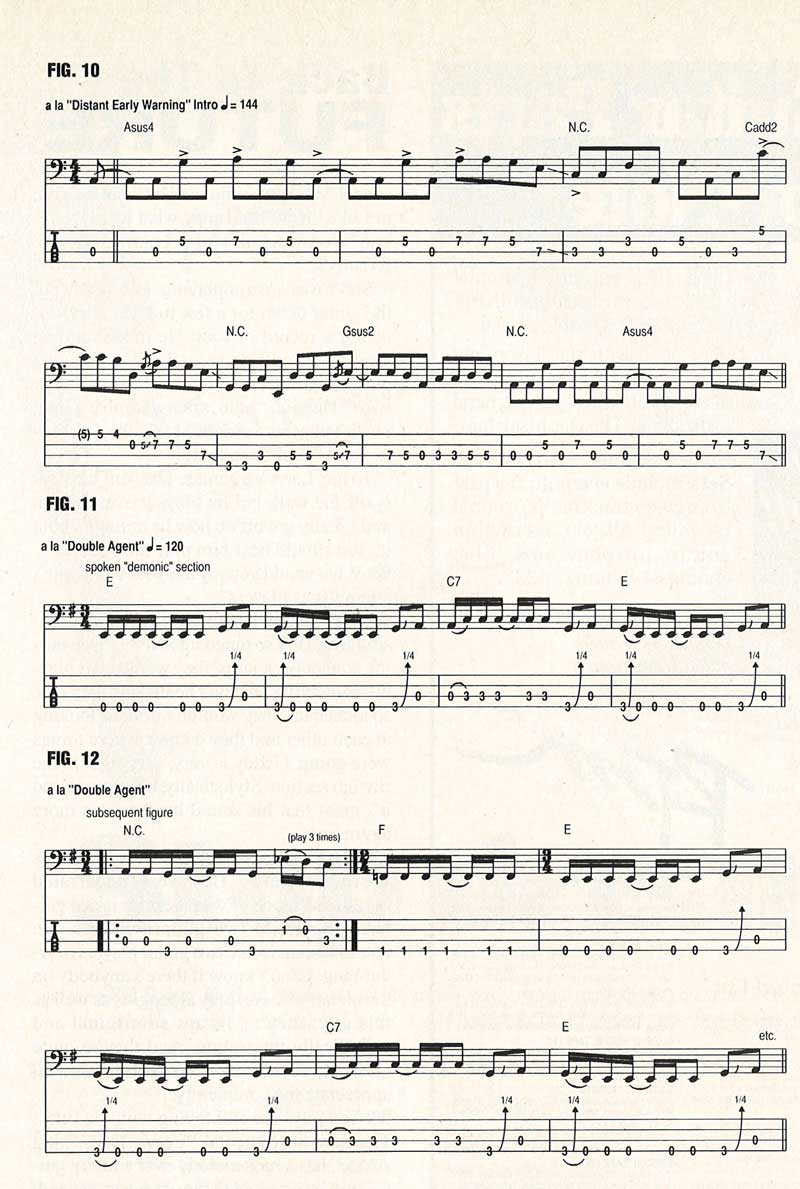

GS: The "Distant Early Warning" bass line is, to me, a prime example of the "Geddy Lee concept." Those shapes show up in a variety of other songs.

LEE: Here's the intro figure ... [see Fig. 10] You'll find a similar chord structure in "La Villa Strangiato."

GS: One thing about Counterparts is the near-exclusion of odd time signatures. Was that intentional?

LEE: No, it wasn't, and now that you've pointed that out, I'm upset! If someone would have said something to us before we finished the record, we would have gone back and thrown some odd-time bars in! [laughs] Just when you feel comfortable listening to a song, we like to drop a beat someplace, hopefully causing you to hurt yourself. On the new record, there's a weird pause, some odd-time thing, on "Nobody's Hero."

GS: Another great bass line from Counterparts is the one you play on "Double Agent," behind the spoken section.

LEE: Yeah, that's another one in 3/4 [see Fig. 11]. When we get to the end of this figure, we like to switch hard into the next part. [Behind the lyric, "Bound up and wound up so tight ": See Fig. 12]. You feel like you're going back around again, but just before you do, you get onto something else! This song will give you another upset stomach! [laughs] We saved a lot of the weird stuff for that song. Those hammer-ons and pull-offs on beat 1 of each bar are examples of getting inside the beat and pushing it along. It's a good way to get it to groove, even though it's an uncomfortable number of beats. It's got an internal groove.