Interview With Neil Peart

Rag, May 1994, transcribed by John Patuto

There are many great feats in life, not the least of them is staying together for 20 years in the mercurial world of rock music without a personnel change.

So even if its progressive music, which explores the interiors of our world and outer worlds happens not to be what you embrace; Rush deserves to be embraced in a congratulatory moment for its accomplishment.

Twenty years. Two decades. An eternity in rock'n'roll. And still new fans join the fold of these Canadian hard rockers who have forged their own art out of power and intellect.

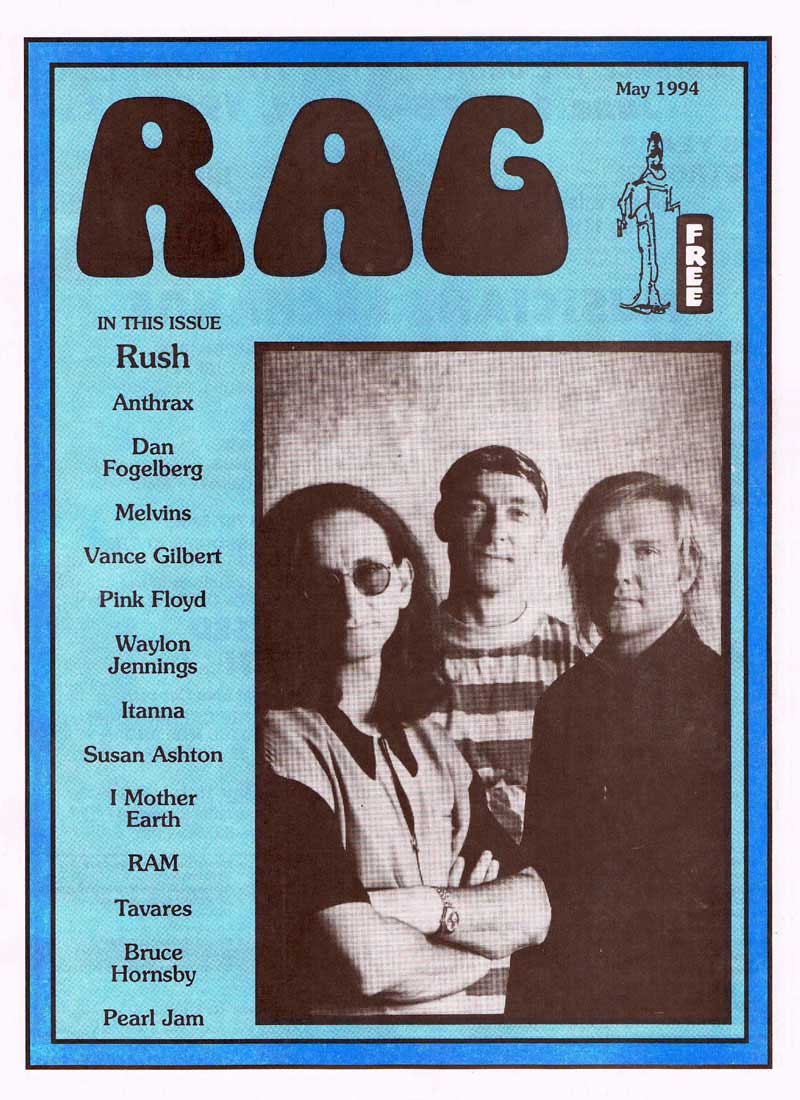

Through the '70s, the '80s and now the '90s, Rush has been Geddy Lee - he of the voice for which a taste must be acquired - on vocals, bass and synthesizers; Alex Lifeson, electric and acoustic guitars; and lyricist Neil Peart, drums.

"I don't think we necessarily have brought anything new to rock," says Peart, 41. He prefers to cite what he calls "The torch bearer analogy. It's passing the torch down to another generation," he explains. "Rush has held aloft musical values through the dark days of the '80s," he says.

That's why Rush is often cited as an influence by so many '90s bands, he adds. "We were one of the few bands through the machine-made music, days that were totally programmed and controlled by record companies, that resisted that. Suddenly in the '90s we're not alone. All these other bands now are emphasizing good musicianship and songwriting again. That's very affirming to us. We just held the torch through the '80s and gave young musicians an example of the way it could be done."

All of which might explain why Rush, in addition to longtime fans, finds itself popular on college campuses too. The band has fought "long and hard" for developing new audiences, Peart says. "It's no accident. The credibility we have is genuine and very hard won. In the '80s, there was a lot of posing by other bands and doing exactly what an A&R (artist and repertoire) man says. For us, it hasn't been that. That's why younger people can sense that it is real for us. With a lot of bands, you wonder if they are trying to be good or popular. It's implicit in our music that we are trying to be good.

The 19th attempt at that arrives in Counterparts, Rush's new album - 11 new songs with music by Lee and Lifeson and lyrics by Peart. Returning as co-producer with Rush for this album is Briton Peter Collins, who co-produced Rush's Power Windows (1985) and Hold Your Fire (1987). Collins, says Peart, "is dedicated to the song above everything else."

The goal for Counterparts was "to get ourselves excited," Peart explains. "That's a crucial thing when we first go in (a studio). 'Presto' (Rush's 1989 album) and 'Roll The Bones' (the group's previous album in 1991) set us in the direction of accentuating the guitar more, especially in the songwriting end. It gives a different character to the tonality of the record. The important thing from the songwriting end is writing with a guitar approach (in mind)."

Rather than one theme, the album, suggests Peart, is "an umbrella title" over several subject areas. "There is relationship: between the sexes and among the races addressed there," he says. "And homosexuality to transcending life's dark experiences, and there's the issue of heroism, the dualities of counterparts." Dualities such as gender or race are not opposite but true counterparts, he says, the same and yet different, and they should not be competitive.

Pretty heavy stuff for rock'n'roll, perhaps, and likely a reason that Rush has been thought of in some circles as a "thinking person's rock band." That description is "kind of elitist," says Peart, "which I don't like. But it's certainly true that we think about what we do. Our music is a reflection of our interest. It is made by thinking people for thinking people. We never talk down to our audiences. I presume they are as smart as we are."

"Stick It Out" and "Cold Fire," two cuts from the new album, already have spent time on the national album rock charts. Peart says "Stick It Out" is both a plea for fortitude and forbearance.

Peart says he appreciates being able to address some of the heavy questions of life. "Yes, I have the luxury of time (between albums) to sit and look out the window all day and feel I'm doing my job (compiling material for lyrics). There's a curiosity about life and interest in life and desire to have more. It's a luxury that I'm allowed to be contemplative. There are common interests and excitements I can take time to articulate for people. That should be our role."

Peart says he still employs considerable Biblical imagery in his lyrics "which I picked up as a child. I just encouraged my daughter to sign up for 'world religions' in high school. You should know those things. It is some people's solution to a problem."

Peart's background is Protestant. He implies that he no longer is involved with organized religion. "If there is life after death, I'm prepared for it," he says. "I think I've lived a good, responsible, moral life. But at the same time, only in service of my own idea of that. I think we are self-contained units of life and have to make the best of what we have here. Your job is to live a good life here and now. I hate the excuse 'it doesn't matter what your actions are here.' Spirituality is often a way of problem solving for people. They have needs or questions they can't answer and they accept religion to help them."

The source of creativity for Peart, one of rock's most intriguing lyricists, is excitement. "I get excited about things. The joy of creation is a small little spark," he says. "Suddenly you realize it's going to work. That's the joy you get - that it's going to work. Then you have to make it work. That takes another few days of craft. The little spark gets me interested."

There is a spiritual dimension that is part of this creative process, he says, "but not in a religious sense. I'm conscious of the gray zone between conscious and unconscious ('Double Agent,' on the new album, explores this gray zone). A lot of my songs talk about that moment between sleep and waking. If there is a spirit and soul in between the conscious and unconscious, mysterious connections come about. That's probably where we must reside. I've had my subconscious make decisions for me."

Ultimately, Peart wants listeners to take a sense of optimism from Rush's music. "Absolutely," he says. "One of the fundamental things is the self-accentuation principle, transcending the tragedies of youth."

Peart is intrigued by the process of creativity. It's about "enjoying the mountain while we're climbing it," he has said. "I like both the process and the results," he says. "My favorite kind of job is one that is finished. But I do love the process of it." Still, he says, the best part of a long bike ride (and he is an avid cyclist) is when it is done."

After 20 years, he says it can be "the little things" that continue to keep it all fresh for Rush. "Drumming is a perfect example. Riding little things, new techniques that spark my interest for months even after all these years. There are still fresh, little things that turn up. I do quite a bit of prose writing too."

The pursuit of happiness continues to be the "little victories, the small victories of everyday life" that make you happy, he says.

This business of music comes with its own dualities. There are the joys and there are the negatives such as the erosion of privacy, he says. "The only thing worse than touring is not touring," Peart suggests. The way to come to terms with it all is deciding what to do in any given situation, he adds.

"It's another example of a kind of morality," he says. "It has to be done well. The drive is there. It's good for me as a person despite how unpleasant it can be at times. It's the right thing to do to keep this band viable and exciting and under test. There is nothing more challenging than walking up on stage in front of an audience and delivering."

Audiences this time around can expect surprises, he says. "It's quite a remarkable new production. We scrapped a lot of the old production." It is starting to approach Broadway proportions, he says.

Performing in an arena to 10,000-12,000 people is not a time to pretend you are in an intimate setting, Peart says. "You just make it the best show you can and try to bring out the nuances in songs perhaps visually or in other ways," he says. "When you see the songs live, it really reaches you in a way the record didn't. There is a possibility of going beyond what people have already gotten out of your music. It is so satisfying now watching this show come together and the level of sophistication and detail work."

Concert audiences reflect a mix of ages. Peart senses that the perception of the band "is kind of strange. People who are aware of us are people who like our music. We don't get much publicity beyond that. There is a certain perception by people who are aware of us and who don't like us. Our fans for the most part are the ones who pay attention to what we do. We established such a track record. Anyone who knows us should have the perception that we work hard and enjoy it. We pay attention to the real details. We take care to imprint our set of values on it. The same values that apply to our music extend through our organization."

One reviewer wrote that for him Rush captures the sense of adventure in a song. "Those things shouldn't be remarkable," Peart says. "There is a sense of adventure about what we do. It's setting on an adventure. If something happens we adapt to it."

Music can be a powerful force, he suggests. "There are levels on which it can touch you emotionally and physically. My response to Italian opera is emotional, but it feels physical, like a physical thrill through my body. Rhythm is like that. It makes me start twitching. It produces a physical response. In the same way, a good book or really good movie gets me excited."

Art, he says, is "kind of like travel. Travel broadens you, it absolutely does. Music and art in the same way, does expand you. Any good art can do that. It expands your experience of humanity. More people understand that is a very important thing in the modern world. That's why I'm interested in the gender and race questions (as treated on 'Counterparts'), apart from the political aspects. I want to think and write about them in a responsible way. I did some travel in Africa and I really do understand Africans now."

In the final analysis, the members of Rush are doing what they always wanted to do, he says. "It was our dream as kids to be in a rock band making records and doing tours," he says. "We are still living that dream. At the same time there are other places I want to travel and other skills I want to learn about. I've studied German and French."

Success, when it comes down to it, is no more nor no less than the pursuit of happiness, Peart says. "It's a very underrated principle of life," he says. "Life is a process and happiness is too. All these things I've mentioned are part of the process. I know a lot of people are living lives that are much lower profile than mine, but are none the less happy. It's inspiring to see that. Happiness is not about economics, that's for sure."