A Port Boy's Story

by Neil Peart

St. Catharines Standard, June 24 & 25, 1994; transcribed by Jeff Robertson

Neil Peart is the drummer and lyricist for Rush, Canada's most successful rock band, who have sold more than 30 million records worldwide, and have performed throughout North America, Europe, and Japan. Neil grew up in St. Catharines, and lived in the area until 1984. These days, when not touring with Rush (or on his bicycle), Neil divides his time between Toronto and the Laurentians area of Quebec, with his wife Jacqueline and daughter Selena.

Written exclusively for The Standard, Neil offers some of his recollections of growing up in Port Dalhousie during the '50s and '60s.

MY STORY begins in 1952, on the family farm near Hagersville. Mom tells me they used to wrap me in swaddling clothes and lay me in a manger, but don't get me wrong - this was no Christmas story. They just wanted me out of the way while they did the milking. But the dimly lit barn, redolent of straw and manure, was an early imprint, and to this day a dairy farm always smells like home to me. Wherever I may travel, from Switzerland to Senegal, my deepest memories are triggered by ... cow dung.

Still, after a couple of years I became restless with country life, and convinced my parents to move to the big city - St. Catharines. My father became parts manager at Dalziel Equipment, the International Harvester dealer on St. Paul Street West (gone now, but I worked there too in later years, right before I joined Rush). Our little family settled briefly into an apartment on the east side, then into a rented duplex on Violet Street, in the Martindale area.

A year later, the stork brought my brother Danny, and sister Judy a year after that. They were nice enough siblings, but I really wanted to be an only child - I never liked to share.

We only lived on Violet Street until I was four, so my memories are few, but I do remember tumbling off my tricycle and falling headfirst into the corrugated metal pit around the basement window, crashing through the glass to hang upside-down, staring at my mother as she stood, drop-jawed, at the wringer washer. Miraculously, I wasn't injured - although in retrospect, I may have suffered a little brain damage. It would explain some of my behavior in later years. But it didn't discourage my early taste for pedal-power, or adventure travel, for 30 years later I would find myself cycling through China, many countries in Europe and West Africa, and around much of North America.

In 1956, we moved to a brand-new split-level on Dalhousie Avenue - then Queen Street, before the imperialist forces of St. Catharines invaded Port Dalhousie, in 1961, and amalgamated it (like Saddam Hussein amalgamated Kuwait, it seems to me).

Our new subdivision had until recently been an orchard, and four pear trees remained at the end of our yard (over the years we ate so many pears off those trees that I have never been able to eat them since). Just behind us was Middleton's cornfield, which occupied the middle of the block, and in late summer it became a cool green labyrinth, perfect for hide-and-seek in the long twilight hours.

My Dad built us a swing set and a sandbox, and with those pear trees to climb and the cornfield to run through, our backyard was nearly perfect. We needed a pool and a trampoline, and maybe a roller coaster. But life was pretty good.

In those days, we didn't know about day-care centres or nursery schools, but Grandma Peart lived in a house on Bayview - right across the cornfield - and often looked after us, especially when Mom started working at Lincoln Hosiery. Grandma played hymns on the pedal organ, baked amazing pies and buns, taught me all about birds from her little colored books (I have them now), made quilts with her friends from the United Church Ladies Auxiliary, and wore her hair tucked in flat waves under a net.

She was a classic Puritan grandmother: wiry and iron-hard, a stern disciplinarian - her chosen instrument was the wooden spoon, applied to my backside with enough force to break more than a few of them - but I also remember a million acts of kindness. And if she believed the injunction against sparing the rod, she could still "spoil the child" in other ways, and we also knew her innate softness, her pure gentleness of heart.

I remember staying at her house when I was small, and at bedtime she would emerge from the bathroom totally transformed: leaving behind the severe cotton dress, the hard black shoes, and the strict hairnet, she tiptoed into the dark room on bare feet, wearing a long white nightgown, her hair down in a rope of grey braid. She seemed so frail and girlish as we knelt beside the big wooden bed to say our prayers: "Now I lay me down to sleep..."

I STARTED kindergarten at MacArthur School, and the first time the fire alarm went off, I ran out of there and didn't stop running until I got home. I had much to learn about life.

From grades 1 to 5 I attended Gracefield School, at the other end of Port Dalhousie, which was still surrounded by fields in those far-off days, and a copse of trees which we poetically called "Littlewoods." Once I fell out of one of those trees, landing on a broken branch and tearing a gash in my inner arm, big enough that I could see the white bone.

An older boy from down the street, Bryan Burke, had the presence-of-mind to rip off his T-shirt, wrap it around my arm and get me home, so after Mom got me to the hospital and had it stitched up, the only permanent damage to my future drumming limb was a long, ragged scar. Thanks, Bryan, whereever you are.

Port Dalhousie in the late '50s was a magical time and place, perfect for boyhood. Quiet streets for ball hockey, the lake for swimming, skating on Martindale Pond, the library to feed my growing appetite for reading, and hordes of other "baby boomer" kids around to share it all.

We measured our lives not by the seasons, but by the ancient festivals - children are natural pagans. Winter was Christmas, spring was Easter, and autumn was the magic of Halloween: dressing up as Zorro, or a pirate, or a hobo, and wandering the cold, dark streets in search of flickering pumpkins at doorways where people would fill our bags with loot.

Whispered words were passed among the ghosts and goblins, and we learned which houses were giving out fudge or candy apple (no fear of needles or poison in those days - before people became so crazy. I blame the water).

Summer, of course, was a long pagan festival all its own. I would get together with a friend like Doug Putman, or my brother Danny, and we would hike or ride our bikes to Paradise Valley, out by Ninth Street, or farther, to Rockway and Ball's Falls. Somehow nothing was more attractive than "the woods" - a bit of leafy forest, a stretch of running water, maybe a shallow cave in the rocks of the escarpment. This was Romance and Adventure.

Sometimes we would ride to the railway crossing at Third Street, and just sit in the culvert all day, listening for trains and running out to watch them go by. Perhaps that sounds as exciting as watching grass grow, but for those apocalyptic seconds when we stood by the track and felt that power speeded by so close, so loud, and so mighty that the earth shook and the wind roared, it raised more adrenalin than any Nintendo game.

We could explore along the wilder parts of the lakeshore, maybe sneak into old man Colesy's orchard to pilfer some fruit (risking his fabled pepper gun), or just spend our days "messing around" down by the old canal, or over by the lighthouse on the "Michigan side."

We would often see old mad Helen walking fast across the bridges, a blade of nose, protruding teeth, and a thatch of grey hair racing ahead of her old overcoat and blocky shoes. Helen was always muttering to herself as she stalked along, and adolescent boys, hiding under the bridges to listen, could imagine as much profanity in her gibberish as we did in the lyrics to Louie Louie. But in reality, only our minds were dirty.

And no wonder - we lived in a dirty world. Like all that generation of Port kids, I learned to swim in Lake Ontario, at Mrs. Stewart's classes, and not only was that water cold on dark days, but what a cesspool we were swimming in - algae and dead fish washing along the shore in reeking piles, dotted with "Port Dalhousie whitefish" (used condoms). Aside from the cold water and the stench, we sometimes endured eye, ear, and throat infections, and indeed, this was only a year or two before the scary signs began to go up: "No Swimming - Polluted Water."

PERHAPS PEOPLE are more used to such things now, but to a 10-year-old boy in 1962, this was an inscrutable mystery. How could this happen? How could people let this happen? Everyone said it was because of the factories in Hamilton, and the pulp mills in Thorold, but of course the worst problem was fecal coliform - human sewage - just as it is today.

In any case, it wasn't the water in Port Dalhousie that nearly killed me - it was other kids. One time, at about the same age, I was swimming 'way out over my head, trying to reach a raft which was anchored a couple of hundred yards offshore. The bigger guys used to swim out there, and I'd done it once before, but I was not a strong swimmer, and shivering added to the exertion. Choppy waves broke in my face, and I choked a couple of times. When I finally made it to the raft, I was gasping for breath and my arms were heavy.

A bunch of the neighborhood bullies were playing there, wrestling and throwing each other into the water, and they thought it would be a good joke not to let me on. Exhausted and desperate, I paddled from side to side of the raft, but they would only taunt me, laugh, and push me away. I started to swim back to shore, while they lost interest and turned away again, back to their rough play.

I couldn't do it. About halfway I ran out of strength, and in a panic realized that I was going to drown. I couldn't move my arms and legs any more, and I felt myself sinking - even had my brief life flash before my eyes. I suppose I must have called out, for the next thing I know I was waking up on the beach. It seemed I'd been pulled from the water by two other kids from school - Kit Jarvis and Margaret Clare (and yes, I remember the names of some of the young brutes on that raft too, and since I've never again been comfortable away from shore, even though I've become a strong swimmer, I can tell you that those guys are doomed forever by bad karma and voodoo curses). On the positive side, I owe Kit and Margaret a lot - in fact, everything - and I've never forgotten what they did.

Nor have I forgotten the simple joys of childhood: riding in the back seat of Dad's red '55 Buick hardtop, squirming against Danny and Judy, all of us excited to be on the way to a drive-in movie (always pretending to be asleep when we got home, so Dad would carry us to our beds).

OR THE RAREST luxury - going out for dinner at the Niagara Frontier House, a diner on Ontario Street which was modest enough, but seemed like the Ritz to me. Red-upholstered booths, lights glinting on wood, Formica, and stainless steel, the Hamilton Beach milkshake machine, the tray of pies on the counter, and the chrome juke-box beside each booth, with those metal pages you could flip through to read the songs. Although the highest luxury of all was being allowed to choose from a menu, I always ordered the same thing: a hot hamburg sandwich and a chocolate milkshake.

Simple joys, and simple sorrows, yet felt as deeply as they will ever be. And sometimes they are both evoked just by remembering an old car. One time we drove out Lakeshore Road and up the lane to Mr. Houtby's farm, and Dad got out to talk to him. Next morning, I started my first summer job. In retrospect, I have to wonder if Mr. Houtby had some grudge against my Dad's farm equipment business, for I found myself sent out to weed a potato field - by hand - and after three days of crawling through the dirt on my hands and knees under the baking sun, I received the princely sum of ... three dollars. My faith in the work ethic was shaken, I can tell you, but it was later restored - first by a Globe & Mail route, then by a little set of red-sparkle drums. . . .

IN EARLY adolescence, my hormones attached themselves to music. Mom and Dad gave me a transistor radio, and I used to lay in bed at night with it turned down low and pressed to my ear, tuned to pop stations in Toronto, Hamilton, Welland, or Buffalo. I still remember the first song that galvanized me: Chains, a simple pop tune by one of those girl groups, with close harmonies syncopated over a driving shuffle. No great classic or anything, but as I listened to that song on my transistor, suddenly I understood. This changed everything.

Rhythm especially seemed to affect me, in a physical way, and soon I was tapping all the time - on tables, knees, and with a pair of chopsticks on baby sister Nancy's playpen.

At first Mom and Dad probably thought I had some kind of nervous affliction, but they decided to try occupational therapy - for my thirteenth birthday, they got me drum lessons. This changed everything even more.

Every Saturday morning, I took the bus uptown, and climbed the stairs to the Peninsula Conservatory of Music, above St. Paul Street. My teacher was Don George - someone else to whom I owe a lot. Don started me off so well: he emphasized the basics of technique (the famous 26 rudiments) and sight reading, but also showed me the flashier stuff, and was always enthusiastic and supportive. Coincidently, Kit Jarvis also studied drums with Don, and Don once told me that out of all his students, only Kit and I would ever be drummers. For me, that was heavy encouragement indeed, and he was fortunately not wrong - I wonder if Kit still plays? Last I heard he moved to Ottawa or something. But of course, that was almost 30 years ago.

I was totally obsessed with drumming and no one ever had to encourage me to practice - to the contrary: I had to be encouraged to stop! By this time we lived on Gertrude Street, and the Kyle family next door was very tolerant and pleasant about the racket pouring out of my bedroom window every afternoon after school.

My drumming debut took place at St. John's Anglican Church Hall in Port Dalhousie, during a school Christmas pageant (no, not as the little drummer boy). Four of us mimed to the Stones' Get Off My Cloud, only since we were supposed to be the Royal Bakers in the play, we changed it to Get Off My Pizza. Clever.

My next drumming appearance was at the Lakeport High School variety show. With Don Brunt on piano and Don Tees on sax, we were the Eternal Triangle, and we practiced nights at the school. (Don Brunt would drive us home in his Dad's '65 Pontiac, usually with a detour out to Middle Road, where he could get it up to a hundred).

For the variety show we played a couple of songs, including one original which was titled LSD Forever (as if we had any idea - the only drug we knew anything about was Export A!). My first public drum solo was a success, and I will never forget how I glowed with the praise from the other kids in the show (including, I've always remembered, Paul Kennedy, who has done well for himself on CBC Radio). To a kid who had never been good in sports, and had never felt like "one of the gang," this was the first time I had ever known "peer appreciation." I confess I liked it.

IN MY EARLY teens I also achieved every Port kid's dream: a summer job at Lakeside Park. In those days, it was still a thriving and exciting whirl of rides, games, music, and lights. So many ghosts haunt that vanished midway; so many memories bring it back for me. I ran the Bubble Game - calling out "Catch a bubble; prize every time!" all day - and sometimes the Ball Toss game. When it wasn't busy I would sit at the back door and watch the kids on the trampolines, and Mr. Cudney wasn't amused. I got fired. (Early on I had trouble with the concept of "responsibility," but I'm better now.)

And then there were all the bands. Guitars and Hammond organs by then, and five-piece groups with names like Mumblin' Sumpthin', The Majority, J. R. Flood, and Hush.

We practiced in basement rec rooms and garages, living for that weekend gig at the church hall, the high school, the roller rink, and, later, so many late- night drives in Econoline vans, sitting on the amps all the way home from towns like Mitchell, Seaforth, Elmira, and even as far as Timmins, as we "toured" the high schools of southern Ontario.

THEN THERE were the Tuesday night jam sessions at the Niagara Theatre Centre (our very own slice of Bohemia). Impromptu groups were formed among members of various local bands - whoever turned up with some gear, basically - and we played variations on the blues, folk songs, and meandering rock fantasies. This was great training for young musicians, and we got paid for it too - $10 dollars each - which was helpful because none of us made any money from our bands. (Any fees from those weekend gigs went to pay rental of public address systems, loan payments, or new drumsticks.) But the experience of playing all that weird music with all those weird people was, of course, priceless.

When I think back to my early musical influences, naturally I was inspired by many famous drummers, like Gene Krupa or Keith Moon, but closer to home, strangely enough I think of a series of guitar players - local guys I was lucky enough to work with who were such total musicians that they forever marked my vision of how this music thing ought to be done. Players like Bob Kozak, Terry Walsh, Paul Dickinson, and Brian Collins (The Standard's own) taught me to recognize quality and excellence in music, and set an example of total commitment and hard work to achieve these things. I still follow the road they showed me, though I'm glad to say the pay has improved. . . .

SO WHAT was it like to grow up in St. Catharines in those days? Well, as some of these stories will attest, it was a wonderful place to be a boy. I have since written that mood into songs like The Analog Kid and Lakeside Park. For a teenager, however, especially a rebellious and self-consciously different teenager, St. Catharines in those days was not so nice. I have written about that mood in songs like Subdivisions.

The Lakeport years were tough. No, I couldn't say it was hell - I had a few friends, and even a few teachers who could make English or history interesting enough to distract me from thinking about drums, drawing pictures of drums, and playing drums on my desk.

One science teacher and self-important martinet (he used to roam the hallways in a quest to eliminate the evil of untucked shirt-tails), was once disturbed by my tapping in class (as more than a few people were, including fellow students - a girl named Donna once threw a book at me). When I told him that I really couldn't help it, that it just "happened," he told me I must be "some kind of retard" and sentenced me to a detention in which I had to drum on the desk for an hour. Some punishment. I had fun; he had to leave the room.

In those high school hallways of the mid-sixties, the conformity was stifling. Everyone dressed the same, in a uniform-of-choice - Sta-Prest slacks, penny loafers, and V-neck vests over Oxford shirts - and at Lakeport High, the jocks and frat boys were king.

To be both a jock and in a fraternity was the ideal - to be neither, unthinkable. Even by 1967, in our whole school there were only about three guys who dared to have long hair (below the ears, that is), and in the hallways we endured constant verbal abuse: "Is that a girl?" "Hey sweetheart!" "Let's give it a haircut!" and other intelligent remarks. Outside it was worse - bullying threats and even beatings. All because we were "freaks."

Later, when I was out of school and playing full time with J. R. Flood, I went to band practice at Paul Dickinson's house every day, and had to take the bus over to Western Hill.

There were some charming characters on that bus, I can tell you - greasy- haired thugs with football pad shoulders and shoe-size IQs - and how I used to hate that ordeal. Of course, by then I was roaming around with a frizzy perm, long black cape, and purple shoes - but I wasn't hurting anybody. I was just different, and they didn't like it.

One time I went into the Three Star Restaurant, across from the former courthouse, and they refused to serve me because I had long hair (again, below the ears). Being naïve and idealistic, I couldn't believe what I was hearing, and I stood up and made a scene, called the Nazis, went and complained to the police and everything. Rebel without a clue.

And consider how narrow our world was, growing up in the suburbs of Port Dalhousie. Until I was in my teens I didn't know a single black person, or an Asian, or even an American. I didn't know what it meant to be Jewish, and I didn't think I knew any of them either. The Catholics were different somehow, with the Star Of The Sea Church, and I wondered why the kids were kept in a "separate school," but it didn't seem to mean much - we all played together in the streets. A half-Chinese family lived across from us, but my Mom had warned us never to tease their kids with remarks like (she whispered) "chinky chinky Chinaman." We had never thought of anything like that, but she must have heard other kids teasing them and wanted to be sure her children wouldn't. Well done, Ma! But really, I never knew about racism or homophobia or anything antagonistic like that - there was simply no one to fasten it on, because nearly everyone was the same. Or pretended to be . . . .

Like the town of Gopher Prairie in Sinclair Lewis's Main Street, people in St. Catharines in those days were nearly all decent, kind, and friendly - as long as you filled your part of the "social contract" by fitting in; as long as you weren't willfully different.

Non-conformity seemed to be taken as some kind of personal reproach by those bitter conformists, and they would close ranks against you, and shun the "mutant."

IN ANY CASE, my childhood in Port Dalhousie was a good one, and all those later experiences certainly "built character." My life, then and now, might be summed up by Nietzsche's motto: "That which does not kill me makes me stronger."

So I'm strong. As a rule, though, I'm not very nostalgic, and seldom even think about the past, but now that I take this occasion to look back on my early life, I am amazed at how many names and faces come surging up. Old friends and neighbors, of course, but more important: so many people who have made a mark on my life. Schoolteachers, drum teachers, life savers, guitar players, grandmothers, and even Mom and Dad.

And in a world which is supposed to be so desperate for heroes, maybe it's time we stopped looking so far away. Surely we have learned by now not to hitch our wagons to a "star," not to bow to celebrity. We find no superhumans among actors, athletes, artists, or the aristocracy, as the media are so constantly revealing that our so-called heroes, from Prince Charles to Michael Jackson, are in reality, as old Fred Nietzsche put it, "human - all too human."

AND MAYBE the role models that we really need are to be found all around us, right in our own neighborhoods. Not some remote model of perfection which exists only as a fantasy, but everyday people who actually show us, by example, a way to behave that we can see is good, and sometimes even people who can show us what it is to be excellent.

And if we ever get the idea that people from faraway places are all thugs, villains, or lunatics, we can stop to realize that we have those all around us too - right here at home. But I have found, in all the neighborhoods of the world, that the heroes still outnumber the villains.

Editor's note:

Neil was playing drums in 1974 for what turned out to be the last incarnation of Hush (a popular Niagara band with me and Paul Luciani on bass guitar and Gary Luciani on vocals) when the phone call came: would Neil be interested in auditioning for Rush, whose drummer had just quit? (As I recall, someone connected with the bad was from St, Catharines and remembered Neil from his J. R. Flood days.)

Neil actually had to think it over. He was working full time at his Dad's business, and had recently returned disappointed after trying to "make it" as a drummer in England. At the time, Hush members saw Rush as merely a Led Zepplin clone band - 'You're making a big mistake, Neil,' one of us sagely opined at a band meeting.

Of course, the rest is musical history. I like to think Neil served as the catalyst in what has obviously become a tremendous musical and personal partnership with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson. Neil - and the group - has continued to grow lyrically and musically through the decades. Neil, it sure wasn't a mistake.

- Brian Collins, Spectrum editor

Transcriber's note:

This article originally appeared in the St. Catharines Standard on June 24 and 25, 1994, and has been copied without permission. I hereby take responsibility for posting it to USENET (alt.music.rush) and uploading it to the archive at syrinx.umd.edu. Persons distributing it via other channels do so at their own risk. If this file is copied, please do not modify the text formatting (unless the file is being translated from ASCII) and the entire file with all notes is duplicated.

This article had several accompanying photographs:

1. Publicity shot of Neil at his kit, from the Roll the Bones tour.

Caption: "Neil Peart performs live with Rush during the 1992 Roll the Bones tour."

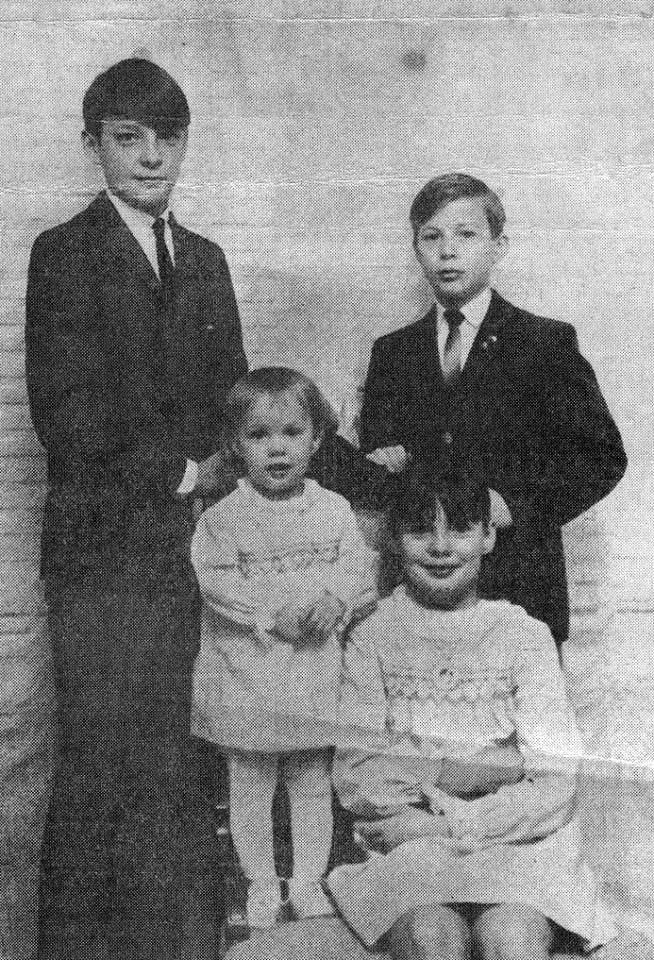

2. Family portrait: Neil, Nancy, Judy, and Danny.

Caption: "Peart and his siblings in St. Catharines, around 1965"

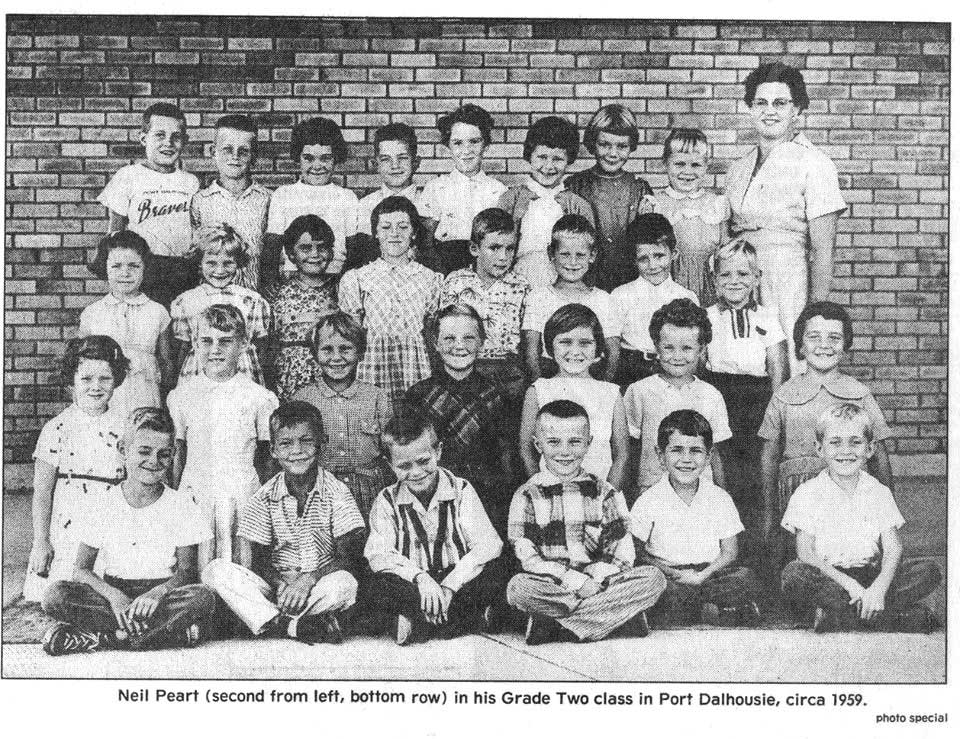

3. Class portrait from school.

Caption: "Neil Peart (second from left, bottom row) in his Grade Two class in Port Dalhousie, circa 1959."

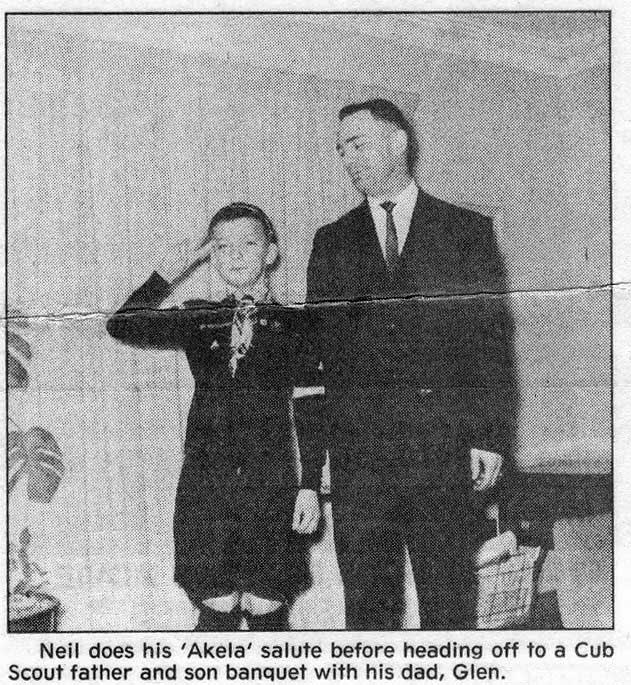

4. Family picture: Neil in his Cub Scout uniform

Caption: "Neil does his 'Akela' salute before heading off to a Cub Scout father and son banquet with his dad, Glen."

5. Family picture: Neil with his drumkit in his bedroom. (The walls have the standard Antique Car motif wall paper that seem a fixture of any boy's room at the time.)

Caption: "Neil Peart practices in his Port Dalhousie home when he was about 15. He had just added a floor tom and two cymbals (and pajamas?) to his first set of drums."

6. Publicity photo of the trio.

Caption: "Rush, Canada's most successful rock band -- Geddy Lee, left, Neil Peart and Alex Lifeson."

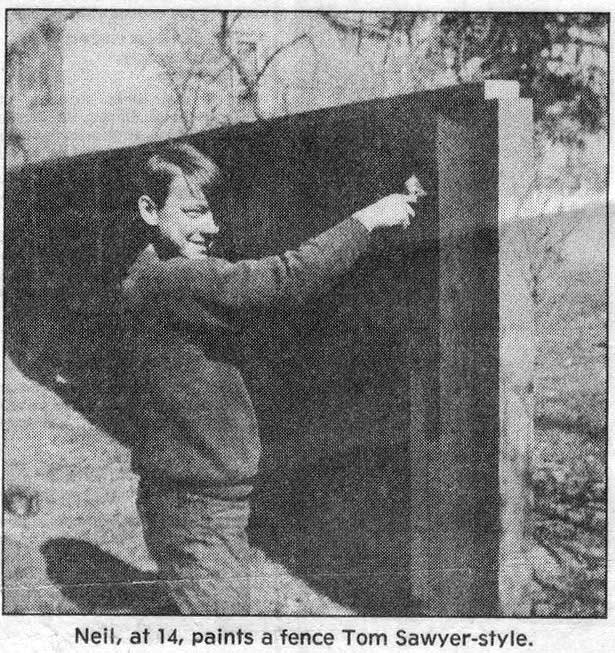

7. Family picture.

Caption: "Neil, at 14, paints a fence Tom Sawyer-style."

-- Jeff Robertson (jeffr@bnr.ca)

Rush Fan and Faithful Transcriber