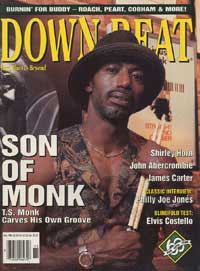

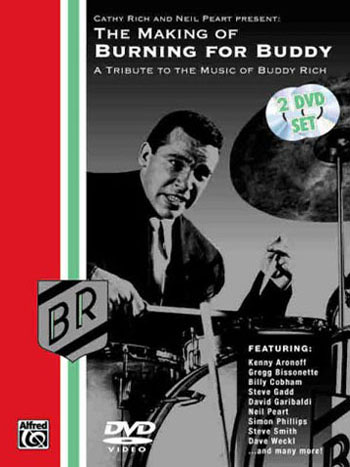

Burning For Buddy

Seventeen Drummers Tackle Big-Band Charts In Tribute To Buddy Rich

By Jim Macnie, Downbeat, November 1994, transcribed by pwrwindows

Teeth and tenaciousness: two things liable to pop into some one's mind at the mention of Buddy Rich. They're part of the literal imagery that surrounded the virtuoso drummer most of his life: that great set of choppers (with which caricaturists had a field day) and that irrepressible verve that sparked every musician within rim shot. The latter dramatically shaped the bandleaders sound, but both remain apt metaphors for the music Rich created. It was gripping and resolute.

"When Buddy let loose, it was 'look out world!"' declares Max Roach. From "Traps, the Drum Wonder" (his nom de Vaudeville, circa 1920, at the age of two), to powering the Tommy Dorsey Band during the early '40s, to lifting up Charlie Parker during New York stints around the time of the jazz at the Philharmonic gigs, to leading the splashy battalion he called a big band from the '50s on, Rich kept his virtuosity front and center. Every move he made was italicized. His music is the essence of emphasis, pulsing with certitude and display Put them together and you've got a very entertaining notion of pride. "It takes a lot of confidence to play as aggressively as he did," muses Billy Cobham.

That being the case, the knockout performances by the 17 drummers on Burning For Buddy, Neil Peart's new tribute to the bandleader stay close to the esthetic that inspired them: They all kick ass.

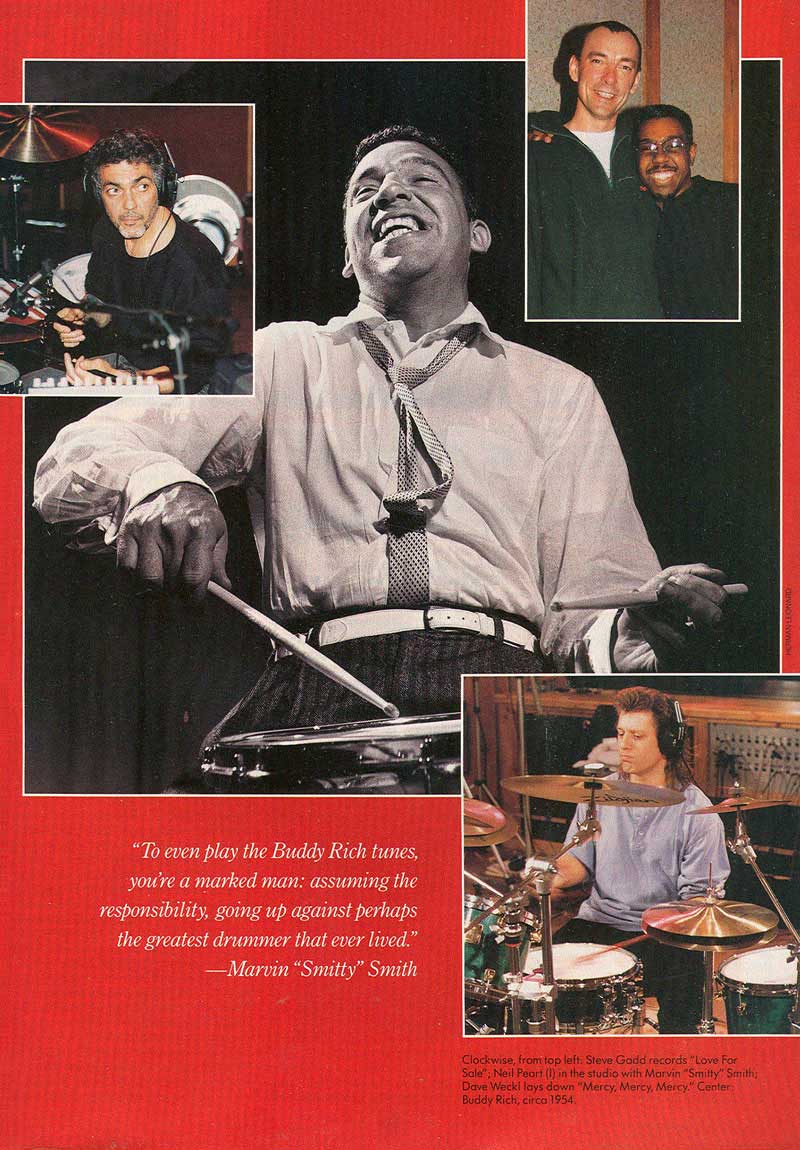

"Buddy was a guy who put out incredible amounts of energy" says Peart. "All of the performances we captured definitely reflect that." From Steve Gadd's "Love For Sale" to Ed Shaughnessy's "Shawnee," he's right on. With the broad span of percussionists invited to participate (besides Peart, Roach, Cobham, Gadd, and Shaughnessy the list includes Kenny Aronoff, Manu Katché, Steve Smith, Omar Hakim, Joe Morello, Simon Phillips, Dave Weckl, Matt Sorum, Rod Morgenstein, Bill Bruford, Marvin "Smitty" Smith, and Steve Ferrone), there's an intergenerational, pan-stylistic breadth at work. For a few weeks last winter, New York's Power Station had a virtual revolving door through which breezed rockers, funkers, and jazzers. All were juiced about tackling a Buddy Rich chart.

"The feeling of commitment and attitude was palpable in the air" explains Peart's coproducer and Buddy's daughter Cathy Rich. "People would come into the room and immediately ask, 'What's going on in here?' The vibe was unmistakable."

Some players knew the material cold. "I am a Buddy fanatic," confesses Weckl. "To be honest with you, when I was 14, I practiced to his version of 'Mercy, Mercy, Mercy' all day long." "Smitty" Smith had a head start on the competition as well. He did a mini-tour with Rich's big band a few years ago. "The last gig was near the local college of my hometown, and by that time we were killing. So when I got to this session, it was simple: 'What do you want me to play man?' Bam. All done."

Peart himself was a bit more intimidated. "Make that enormously intimidated," he amends. "It takes a while to get the feeling of swing to sound natural."

For the last 20 years he's been the drummer for Rush, a band of Canadians that combines rigorous structural designs and a performance derring-do that has sated those who like their prog-rock cerebral and gutsy. He isn't the first rocker who wanted to sit behind the throttle of a big band (the Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts beat him to it). But, along with Cathy and her husband, Steve Arnold, he's put together a vital, well-rounded record that spotlights individuality while genuflecting to a hero. "One reason the record's a hoot is because Neil was so enthusiastic," accounts Roach.

It's an album that brings up the question of whether rock drummers have an aptitude for jazz. Rich's music contained the kind of animation that could crumble walls, full of chatter and blurts out of nowhere. He was an accent hound in the guise of a pressure cooker who, at any given moment, might flam the audience into next week. Rockers should be used to that, but raising the roof in a different musical language remains a daunting task; lessons must be learned, skills developed.

Peart knew the feeling firsthand. In '91 he participated in a concert for the Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship Program, playing with the highly regarded Buddy Rich Big Band (who, Roach reminds, "are a hell of a band" and make this record what it is). There, he didn't really feel his performance of "Cotton Tail" was up to snuff. "Neil's meticulous about everything he does," offers Cathy. Peart's chance to right the situation came when Rush took a hiatus due to a birth in the band. "The studio is a much more controllable atmosphere," he chuckles. "Let's just say I got much closer to really playing 'Cotton Tail' this time around."

On November 6, there's yet another chance for some of the Burning For Buddy drummers to address their tunes. Weckl, Peart, Ferrone, Aronoff, Morgenstein, and Sorum will play at this year's Buddy Rich Memorial Scholarship concert at the Manhattan Center in New York City.

We spoke to some of the participants of the Burning For Buddy project, which will have at least one more edition released somewhere in the future. ("Volume Two is more swing-oriented," explains Peart. "I call it the 'cruise volume`: just put it in the car [stereo] and drive on.") Memories of Buddy himself dominated the conversations, but the topics also leapt to a drummers duties, the hows and whys of personal style, and the rigors of competition.

Max Roach:

Buddy's band was one of the few left after the demise of the big-band period. [Count] Basie's, Duke [Ellington]'s, Woody [Herrman]'s ... only a few lasted through the heavy expenses of road travel. They were the only ones making noise. Plus, that's a great band. So I think we all were involved for the same reasons - out of respect for Buddy's contributions, and what he did for people.

Buddy and I had plenty of wars together! One of the most memorable was when I started to win the polls in the magazines, "the youngster from New York," you know? I was invited to Southern California, and was escorted by Clark Terry. It was Buddy, Gene Krupa, and Louie Bellson. Me, Dizzy [Gillespie], and Bird [Charlie Parker] were the talk of the town, and I felt good, really strong. But I knew who I was up against. Buddy was strong that day but the guy who took out everybody was Gene. He razzle-dazzled the shit out of us. Buddy and I were competing with each other and we learned a real lesson from Gene that day. Play to the audience. He had them rolling in the aisles. Ha! It was a lesson in show biz that Buddy never forgot.

He was more than just a natural, he was a phenomenal technician, too. Shit, he knew the instrument inside and out. He took some really hip solos. I grew up watching him develop "Quiet Please." He was one of the guys who helped bring percussion out to the front. You know the old jokes: "Who's in the band? Three musicians and a drummer." Some guys really believed that. We had to endure a lot of that crap. So Buddy's talent, and that of Chick Webb, Gene Krupa, and a few others turned that around. It's much more than just keeping time for everybody.

Marvin 'Smitty' Smith:

Cathy Rich set up five or six gigs with me and the band back in February of '92, and it was cool. When we went on the road, the guys in the band liked me because I really dealt with the music. I was talking to [saxophonist] Steve Marcus, and he explained that some of the other drummers who sat in when they were trying to keep the band going [after Buddy's death in 1987] - well, it was painful sometimes. They didn't deal with the music in a sincere manner. There was too much Buddy in them, or too much something else, I don't know.

I had a firm foundation regarding the concept of big band, plus a positive demeanor with the guys. It was, "Lets do this right, and when it comes to the very first note, lets burn." Be there for the main cause, the music.

We want to show people we're serious. I think that's a great attitude. It made it fun. Great experience to play the band book. Hearing the sound of the big band is great - all that power around you! And it feels great knowing that you can support it. I tried to do it justice, and not to play like Buddy - that would be the downfall.

To even play the Buddy Rich tunes, you're a marked man: assuming the responsibility going up against perhaps the greatest drummer that ever lived.

Dave Weckl:

I grew up playing big band - it's always been fun for me. You have to be ... you're responsible for 15, 16 guys, depending on the band. The key for me, and what I always admired about Buddy is trying to get it to the point where you can be as free as possible creatively and still make it work. He could play exactly what he was thinking without worrying, "Hey am I playing something the band can follow?" Buddy played what Buddy played, and the group trusted him and followed. That's my goal, too. Especially in a big band: Live in it with the freedom of playing the way I want, but with the understanding of the rules. You've got to set up the guys.

Buddy's band wasn't like Mel Lewis' or Basie's band. There, it was cool to lay back a bit. The horns would lay behind and that was part of the feel. That would never work with Buddy's group. I prefer it when the horns have the same kind of time as the drums. I used to get into this with high-school pals, analyzing the time-thing of big bands when I was a kid. The band responds to the way that the drummers time feels. At the Power Station sessions, I was trying to play in the spirit of Buddy.

Neil Peart:

I really wanted to carefully present the record to a modern audience. Accessibility was always in the forefront of my mind, knowing that many listeners are unfamiliar with the feel of swing.

I always recall the way reggae was first heard in popular music: people were so funny because they didn't know how to dance to it until they got used to the knee action. Swing is like that for some - if you don't know how to react physically it can leave you sort of cold. So the sequencing was crucial. I carefully added hints of swing with each track, and waited until "Cotton Tail" to fully introduce it.

I was like most people of my generation with Buddy. I saw him do "Dancing Men" and "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy" on the Carson show and they stuck in my mind. They're so dynamic, they'll nail you immediately. People around the project who weren't familiar with jazz responded to them right away during the sessions. It's a matter of presentation. I'm determined to take it beyond the regular audience of Buddy fans.

Honestly, I think this project would have been a lot harder to get done if I didn't have a track record with the company already. [Atlantic Records co-founder] Ahmet Ertegun came down to the studio; he was very interested in it, and in a sense he first planted the seed for this. When Rush signed with Atlantic about six years ago, he came up after a show and pointed his finger in my chest, saying, "I've got to get you playing some jazz." So he predicted it.

This kind of project can be enormously intimidating for drummers, especially if you're unused to the feel of the music. Some stayed in the funk or rock-oriented tracks. But two of the purer rock drummers, Kenny Aronoff and myself, both dove into the most trad-swing stuff we could, because we wanted to make as far a leap as possible. That carries its risks, of course. There are elements of big-band drumming that I just didn't know and you can't necessarily learn them by dissecting the pieces.

There was a great deal of teamwork and unity. The horn players were startled to be asked their opinion! After a take, I'd ask the guys, "How was it for you?" I can't dissect the playing of 15 different musicians as they're wailing. I sat and listened to the horns a lot, even tried ignoring the drummers a bit by sitting in a place where I couldn't see them. I had to forego those free drum lessons.

All the drummers in my generation started from two sources: Either they saw The Gene Krupa Story, which was my route, or they saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show and wanted to be Ringo. You can listen to most drummers and figure out immediately which is which. There's a major difference.

Joe Morello:

I guess most people think of me as a small-group drummer, so it was fun to play against type. With small-group stuff, it's interplay thats crucial. When you're working a big band, it's holding the band together, cuing the brass that's important. I love it because you can hit the drums a little bit harder, keep the horses going down the right path. "Drumorello" is a thing that was written for me way back. It's just a set-up for the drums.

Buddy's reputation as a hothead came from being a perfectionist: He used to argue with Dorsey, and Tommy was a perfectionist as well. There have been so many stories about him being a rough guy but he was always a gentleman with me. If we were in the same town, he'd always call up and invite me over to his gigs. I think the reason he liked me was because I didn't play like him. There are several guys from my generation who tried to ape Buddy doing all the solos and battles. But no one will ever equal what he did in that style, not the way he played it. These guys had great facility, but you have to be original to have the spark.

I think I was one of the few guys who practiced with Buddy. One time in San Francisco, we were at the Shrine Auditorium and he was in Oakland with Harry James. We went back to the hotel, and it was late. He'd just got some new cymbals from Zildjian. It was 3 a.m. "Look at these," he says. Crash, crash, splash! I said, "Hey man, you're going to get us thrown out of here, Buddy" "Screw 'em." Then he started pounding out some beats on the wall, and I'm thinking about jail. He takes out some sticks, "Whaddya think of these?" and all of a sudden it's 6 a.m. and we're banging out rolls. It was great. He'd say to me, "What do you think of so-and-so's playing?" I'd say "Yeah, he's okay" Buddy would say "Oh come on, he sounds like he's rumbling down the staircase? I'd laugh and laugh at his honesty.

Billy Cobham:

Going into the session, I tried to figure out what was expected, recall the Buddy Rich concept, think of how he projected his ideas through music.

Buddy would call upon his band to reach a certain level that he imagined, and sometimes the band couldn't provide it. I can see how frustration would set in. But he asked that of himself, too. And even his own body couldn't always provide that level. The mind had it, he heard it. But it was physically impossible. You try to do the best you can, and aim high, knowing that you might not achieve your goal. You aim for the horizon and figure if you get 500 yards out, you've made it. It's a heck of a lot better than standing on the shore your whole life. He aimed for things understanding that they might not be achievable. And he came real close.

There are people who provided major incentive for me, and Buddy was one. He played my instrument, I played his instrument. I had a guide in him, Max, Louie Bellson. They gave me a way to go, a path. These are the kinds of cats who lead bands whether it's their band or not. They lead by simply playing. That aggression was an important factor for me enjoying him.

A drummer wants to sit behind the band because of practicality. It's an effective place to be - giving the band security while still projecting yourself. But you don't just support the weaknesses of others. You try to provide an overall musical statement so that there is no doubt that without what you did, no one would play as effectively on either an individual basis or as part of the group. You're the spoon that stirs the soup. That's what Buddy did, and that's what I learned from him.