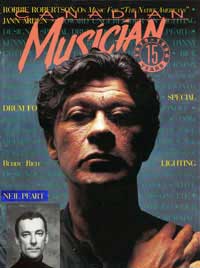

"From Power Trio to Big Band: Neil Peart Talks About Burning for Buddy"

"Bashin' Smashin' Crashin' & Splashin': Drummers Noise Off on Drums"

"Spotlight on Lighting Design"

Articles by Jeff Salem and Howard Ungerleider, Canadian Musician, December 1994, transcribed by John Patuto

From Power Trio to Big Band: Neil Peart Talks About Burning for Buddy

By Jeff Salem

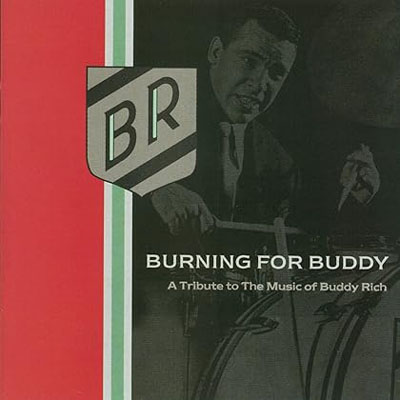

Neil Peart, one of the great masters of power trio rock drumming, recently took on a big challenge. Inspired by a new interest in big band jazz (which he relates to because it's 'architectural' and 'well-organized') and a great love and respect for the drumming of the late Buddy Rich, Peart assembled some of the greatest skin-beaters in the business and produced a tribute album entitled Burning For Buddy. The all-star set features the Buddy Rich Big Band accompanied by Peart, Steve Gadd, Dave Weckl, Billy Cobham, Bill Bruford, Max Roach and many others.

It's a drumming tour-de-force and a musical celebration of the big band sound; and though it's not lacking in swing credibility, it may attract as many rock fans as it will jazz aficionados. Matt Sorum of Guns 'N Roses is one reason why; his contribution, "Beulah Witch", succeeds in applying metal attitude and muscle to the big band format without either disrespecting the genre or compromising his own style. Kenny Aronoff's rousing rendition of the standard "Straight No Chaser" has a similar effect. The marriage consummated by Peart's production is evidence that there's more common ground between the worlds of rock and jazz than many might think. After all, Rich was always open to new musical styles, inviting players like bassist Tony Levin (King Crimson, Peter Gabriel) to play on his albums- and many of the contributors to this tribute, including Rod Morgenstein (Dixie Dregs, Winger), Omar Hakim (Miles Davis, Sting) and Steve Smith (Journey, Vital Information) are equally respected in the rock and jazz communities. As one of the most lively and progressive drummers ever, Buddy Rich would be proud. In fact, he may be jamming in drum heaven with John Bonham and Keith Moon at this very moment.

How did the Burning For Buddy project come about? Have you always been interested in big band music?

"In 1991, Cathy Rich (Buddy's daughter) asked me to be part of the Memorial Scholarship Concert, and though I knew it'd be really scary, I committed to do it. Subsequently, I woke up the next morning and thought, 'why did I say I would do it? I can't do this!' I'd never played the music before and I was going to play with Buddy Rich's band! I mean, it was absurd, really. A foolish thing to dive into but I did, and it worked perfectly because we [Rush] were just finishing the recording of a record and getting into overdubs, so I had the time to rehearse for it and spent a lot of time analyzing what Buddy played and why. I had to I use him for my guide of how to play big band music; and there's nobody better than Buddy- except that I ended up analyzing everything that he did and figuring out all the fills and breaks and stuff, which was a monumental task. But that became part of the challenge for me. It was okay, I'd been doing 'myself' for a long time. I figured, why not analyze how Buddy thought, how he divided up a drum break, all that stuff. It was really interesting to explore. But then, of course, given that it was a live concert with six drummers, the rehearsal time was limited to none, soundcheck was chaotic, the monitors were chaos and I couldn't hear the horns at all. So I was a little bit disappointed, but still, I wanted to do it again.

"So when I found out that Geddy and his wife were having a baby and our tour was going to end in May instead of June, I thought, 'Oh, I've got almost two months off, what'll I do?' and started just playing. That luxury of time seldom comes our way, so when we get two months of time that isn't committed, it's a big opportunity to do something - I could have gone to Timbuktu or across Australia but I thought; no, I really want to play with a big band, so somebody should produce a big band Buddy Rich tribute, and I could play on it! I realized that no one else was likely to come up with it before May - this was January already - so I thought, 'I'd better do it, then'. So I got in touch with Cathy and asked her what she would think of an idea like that, and listed her as executive producer. She contacted the other drummers and all the band members and brought in various people from the Rush organization to cover different jobs for the project. So fortunately, I did have the infrastructure to draw on there. Then we just set it up for the beginning of May, two weeks of recording with eighteen drummers.

"For me to produce something like a Buddy Rich tribute and to play some big band jazz was really the only other style of music I was interested in playing. It has so much in common with our (Rush's) music because it is structured, but it has all the freedom inside for you to treat it how you will. An arrangement of one of Buddy's tunes might be set up a certain way, but Buddy didn't read, so he played it his way, there was no drum chart. And any of the other drummers that came in on this project, they played the arrangement, but they played it entirely their way.

"By the end of our two weeks at the Power Station, we had recorded no less than thirty-nine tunes, or about three hours and twenty minutes of music, and it became apparent that this was not going to fit onto one CD - or even two. Not wanting to put it out as an expensive multi-disc set, we decided to release three individual volumes, hoping that this might entice more people to check out this wonderful music for themselves."

How did you go about selecting the drummers for the album?

"Well, Cathy and I did. She had a list, and the ones she had worked with in the concerts before that had been good, we stayed with. That included several of the guys that I worked with on the '91 show: Steve Smith, Marvin 'Smitty' Smith, Omar Hakim - guys that we just knew were right for it - and guys who had been on previous ones, like Steve Gadd. Gregg Bissonette will be on Volume 2, his tune suited the mood of the second volume more. He's got so much background in the music, he did a superb job.

"Other guys we took a bit of a shot on; Matt Sorum, for instance. But I knew his studio history with The Cult before Guns 'N' Roses, and I knew that he was the guy that bands like that would hire for a good job, fast - the same reason I wanted Simon Phillips. Matt Sorum, to me, was like the American Simon Phillips, the hired gun to do a great job fast. So both of us thought he would probably be good - and he was, he was superb. Some of them, like him, were kind of out in left field stylistically, but basically they were chosen for excellence, and then for appropriateness. They had to be appropriate for the music, you know, they had to be able to do it, essentially!

"I know how much of a struggle it was for me, and guys like Kenny, too. Both of us came from a strong rock world, where that's really all we've ever played, and so it was interesting to me that both of us chose the most radical, complex swing arrangements that we could - the one he did was 'Straight No Chaser', the Thelonius Monk one - instead of doing a rock or funk one, which would have been a much easier reach. Both of us dove in all the way. And it's hard! He was saying there's one little figure that he does in his tune that's the simplest little thing, where the bass drum and snare drum hit a little kick together. It's just two beats and nobody else notices anything of it, but as soon as I heard it, I thought, 'oh, that's gotta be hard...' I talked to Kenny, and sure enough, he'd rehearsed it for days, because it's just this classical thing that rock guys would never do, just a little 'pooh, pooh!', you know? I noticed right away that it would be hard to get and he told me what he went through to get it. And then the single-stroke snare drum break that he does on that tune is also the same thing - it sounds so simple, there's just a sudden 'drrrrrrrrrrrrrrra!', one of the things that Buddy was really known for. Kenny said playing and recording this song allied up to 'that roll- 'Okay, here it comes, here it comes ... drrrrrrrrrra!' You know, it's just one of those things that no other person but a drummer would empathize with, what it takes to deliver some of those things, and why Buddy was so special being able to do that."

That's funny, because Kenny kept on telling me, 'God, that really challenged my butt!'- he kept repeating that over and over!

"Rod Morgenstein went through the same thing, too, schooled as he is even in jazz, on the fusion side of it. He saw it as an enormous challenge. A lot of the guys did. Even Steve Gadd - he came in and said, 'I'll be glad when this is over... ' -he was really nervous! And he's known for that, too, for being a nervous player and nervous about his own ability - which some people find shocking about someone like Steve Gadd, but it's the way you should be. If you come in all overconfident, you aren't giving the job its proper size. It's a huge challenge for anybody, even if you've played the music all your life. You're coming in to make a record with the best drummers in the world, with the best drummer in the world's band, you know? It can't not be big!"

Did you learn anything from any of the other drummers during the recording?

"It was a surprising thing that I couldn't, as producer. I couldn't pay attention to the drummers, I couldn't get all those free drum lessons that I had thought I would ... I thought it would be great to study all these guys and just pick up little things, because that's always such a valuable source of inspiration; you see the guy do something and you try to copy it, and even if you don't succeed, it sends you somewhere. A lot of great things that I've tried to emulate in someone else, I don't, but I come up with something else. I thought this would be that kind of opportunity, but I had to sit where I couldn't see the drummer, close my eyes and just listen to the tune. Everybody had to watch their own performances."

Kenny Aronoff mentioned that the two of you collaborated on a percussion overdub on one track that featured Steve Ferrone.

"Yeah, that was on 'Pick Up The Pieces'. There was a long drum break in it, and Steve just sort of played time through it. He remarked at the time that he hated drum solos. So I said, 'okay, we'll leave it'. Well, then it started to bother me that it was just 'keeping time' for all this break. I thought I was going to edit it out, or do something on it. Then, I thought, well, Kenny and I had hit it off so well and I knew he had a big box of percussion toys, and I ran into him up in Morin Heights where he was recording. I had all my African drums and stuff up there, so we went into the little back room in the studio and just brought in all our toys - 'Well, how about this? Okay, you play that part and I'll play this part!'- and we just put it together spontaneously and I'm really happy with how it came out.

"Especially because it was a friendly thing; he and I had hit it off so well, and here was a chance for us to work together on something less serious, no one watching the clock and no one looking to be satisfied other than ourselves. So it was really nice to do."

Are all the tunes on the album tunes that Buddy played?

"Apart from a few original pieces contributed by the guest drummers, all of this music is drawn from Buddy's repertoire. From his first big band in the late '40s until his passing in 1987, Buddy's music was never about nostalgia. It was always young, and reflected the changing times. He pushed big-band music forward from traditional swing to absorb influences from latin, rock, funk, fusion and contemporary jazz; and all of that variety is represented on this tribute."

Bashin' Smashin' Crashin' & Splashin': Drummers Noise Off on Drums

By Jeff Salem

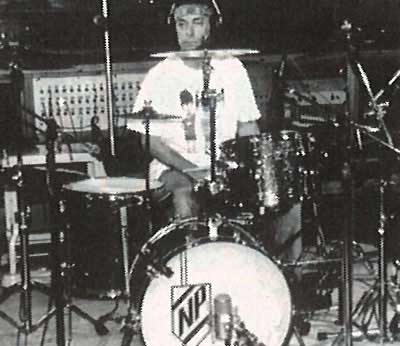

NEIL PEART needs no introduction. A 20-year veteran of the most successful recording act in Canadian history, his work with Rush has inspired a new breed of drummers who will probably be gracing these pages themselves in the near future. A gifted and prolific lyricist, his unique insight and writing style has earned Rush the distinction of being known as 'the thinking man's' rock band. An adventurer, Neil's most recent foray has been into the realm of producer for the landmark Buddy Rich tribute, Burning For Buddy.

Pickin' Up The Sticks

Early Inspiration and Influences

"The Gene Krupa Story was absolutely the spark for me, and at age 13 my parents gave me drum lessons for my birthday, so that's the official start. "The late '60s was fortunately such a great time to be starting out, because the first Jimi Hendrix record was out with Mitch Mitchell, Cream with Ginger Baker, Keith Moon with the Who and so on. So there were a lot of good drummers around in bands at that time, unlike a couple of years earlier; you know, the mid '60s were very dark for drumming in rock music. But by the late '60s, it started to get really cool and then right after that came King Crimson. Michael Giles was a very big influence on me stylistically and arrangement-wise - how to approach putting together a piece dynamically, how to use lots of fills but in a cool way - all of the stuff that I really wanted to do, he would use. He was an important influence. And Bill Bruford, too, Carl Palmer, Phil Collins in the early Genesis stuff - all that played its part in pointing me in different directions. But inevitably, it all becomes such a mix of more people. At first I only knew about Gene Krupa and maybe Keith Moon, but before long there were twelve or fifteen drummers that I was listening to and learning from, so I was no longer pointed in specific directions."

Listening

"I'm less and less stylistically limited all the time, as long as the music is 'nourishing'. I don't really listen on purpose to learn things or to steal things or to hear things, particularly. I listen to be nourished - the same reason music has been so popular for so long, because it nourishes people. It's not a course of study, it's not like something you read to learn something about, it's an end in itself. That's why it's one of the fine arts, because it's final. Music is made to be listened to, or to dance to. So that, for me, is very often enough."

Learning from Other Drummers

"I really believe mostly in teaching by example. And everything that I've learned hasn't been from videos or books, it's been from what guys play. Especially seeing them, but also hearing them on record. And that's been the seed for me for everything, so it seems that ought to be sufficient. But then, I recognize the truth that you have to learn how to hear and listen before you can move in that fashion. I had a teacher, initially, who did point me in all those right directions. So I had a good grounding that allowed me to take off and do it by myself. I guess it's different in different circumstances. Sometimes a video can be helpful, in fact it has been for me. When I set out to learn the djembe drum, I got an instructional video by the maker of the drum and it was enormously helpful because it was a completely unknown thing to me.

"Almost any pointer is worthwhile having. That's why if I were a young drummer, I would be buying all these videos and going to every clinic, even though I didn't have any of that when I was starting. I never went to a drum clinic, never saw a video, none of that. So in that way, I tend to discount it a little. I think everything that I learned, I learned from other drummers; I have no qualms about admitting that. I haven't invented very much at all, most of it has come from other people, so I think if I can learn from all these people, if I'm an influence, then teaching people anything is by example."

The Challenge

"Structure is important, but then again, you have to trick yourself a little bit and not let the structure become the ruler. So I always leave parts that aren't worked out a certain transition, a certain fill, a drum break, a solo section or whatever that I won't let myself work out and make sure that every time I play that it's dangerous. And hopefully, every time, it takes me somewhere fresh. So that's another way of beating the 'over-rehearsed' syndrome, even though I like to be over-rehearsed! Over the years I've learned that if I practiced something too much and came into the studio too well-prepared, it would be stale.

"I'm always working on something - brushes were the thing all this tour. One year I was working on a lot of hand drumming, congas, bongos, etc. I got interested in brushes; it seems to be a dying art. I feel it deserves to survive and it's something I would like to have as a part of my repertoire."

My Band Is Already The Greatest Band On Earth

"Rush is unique in the sense that it's all things to us. Every style of music that I've ever wanted to play, Rush does. Every way I like to playas a drummer, I've done in Rush. We like to structure it dynamically and architecturally, so the arrangement is pretty well constructed, but then within that, we have tons of freedom! It's not restrictive at all. However I want to treat that dynamically and technically as a drum part, it's mine. So, every influence I've ever had, every interest I've ever had musically has gone into Rush. I have no frustrations. I play exactly how I want to play."

Terry Bozzio

"Terry Bozzio is a true pioneer. He was one person who was supposed to be on this Buddy Rich tribute, but he found himself in Europe at the time. Bill Bruford is another guy I consider a pioneer and I find myself often following those guys. For example, when Simmons drums first came out, there was no way I was going to dive into putting up with all that unreliability and the limitedness of their use and all that, but guys like them did. They dove headfirst into the new thing and broke ground for guys like me who come along after and say, 'well, I could use that now' after guys like them have sorted it all out. Bozzio's done a lot of really interesting things. That Jeff Beck album he did a couple of years ago was really interesting. His thinking is so unique and he's a powerhouse, a true pioneer and with so much technique to back it up; he brings an acoustic drum style and language to exploring electronic drums. What he did with King Crimson and the Earthworks stuff was groundbreaking and really important. So guys like that deserve a lot of credit. They seldom settle down long enough to produce a body of work, or their music tends to be too marginal, like with Bruford's stuff in the band Bruford - it was great, I just loved it, but he could never get arrested!"

SOUNDCHECK

In order to be heard over all the bashing, thrashing and crashing found elsewhere in this issue, this month's SoundCheck is being devoted to several recordings that deserve to be heard on the merits of their drumming contributions. Though it's by no means a definitive selection, it does include a fine and eclectic array of drum performances.

Fly By Night, Rush (Anthem Records)

Fly By Night, Rush (Anthem Records)

drummer: Neil Peart

Whatever happened to John Rutsey? When he split the Rush camp, he became the Canadian Pete Best [maybe someone could make a documentary about his early days In the band and call It 'Backbacon'? ... just a joke ...] Certainly, from the first few beats of "Anthem", all memories of him were erased. It's not that Rush's self-titled debut was a bad album, it's just that this sophomore platter [with the attacking white owl on the cover] had mystical Dungeons and Dragons lyrics and the most sophisticated rock drumming the Great White North had ever heard. It's some of Peart's freshest playing, and though "Tom Sawyer" and "Spirit Of Radio" became the all-time air-drumming favourites, there's just something wonderfully young and funny about those tasty little flanged fills In "By-Tor & The Snow Dog".

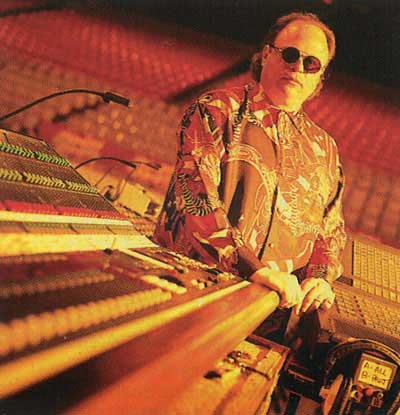

Spotlight on Lighting Design

by Howard Ungerleider

I remember, back in 1971, waiting in line for hours in front of Carnegie Hall to buy a ticket for a Pink Floyd show. Once inside, I noticed that there were speakers everywhere including among the seats in the audience. When I looked at the stage, I saw what looked like unusual towers, a type of staging I had never seen before. My adrenaline was soaring, anticipating the start of the show. Suddenly, the sound of a human heartbeat started thumping and getting faster and faster out of the speakers placed amidst the audience. Then it became one with the beginning of the song "One of These Days". At the same time, the strange towers rose as police car lights, beams and smoke poured over the stage. The band came in with the start of the song and a loud burst of pyrotechnics nearly knocked me out of my seat. I had just experienced my first real contact with an absolutely amazing production.

That was my first inspiration to become involved with the production aspect of concerts and needless to say, since then, concerts have changed dramatically. Gels have become diachronic filters, stationary lamps now move, spin and strobe, the price of the technology has tripled to staggering proportions and only a handful of people can afford to compete in this very expensive game of high-tech production. The ticket price I paid back in 1971 ($15) seems like pocket change compared to ticket prices today ($65 and up). In order to make the price seem reasonable, the production end of a show has to be magnified ... and that's where a lighting designer comes into play.

General Designing Tips

Although I have spent most of my time designing lights and shows for concert tours, I have also been involved in creating for films, video, clubs, trade shows, fund raisers and theatre. Everyone has their own method for designing. I'd like to share a few of mine with you.

A Lighting Designer can make or break a performance. Creating a show can be done in many different ways and each designer has his/her own creative signature. As a designer, you must first put yourself in the seat of a ticket-holder. I will never forget that old Pink Floyd show and the excitement that left me speechless. I try to recreate that excitement by creating and choreographing new lighting effects to each song, bringing them to life with colour and dramatic aura. I like using the atmosphere as my drawing board, filling the air with smoke and using saturated colours to accent the artist's mood. Doing this often helps to create an amazing surrealistic aura throughout the venue.

The use of props, scenery and soft goods can also change the look of a show from a futuristic setting to a theatrical presentation, depending on how you use them.

Multimedia effects can bring certain shows to life. Sometimes I feel there is a need for this along with the lighting. A good example of this would be the use of video walls as scenery with lighting surrounding them as an intertwined laser effect creates the illusion that the video walls are floating in the air. Combining these effects, the world of endless creativity is at your fingertips.

Pyrotechnics have also been an integral part of many productions. Shows from the "Phantom of the Opera" to "Miss Saigon" and "Tommy" all use this effect now. Pyro, as frightening as it sounds, can be as subtle as a light mist drifting over a man-made lake or utilized to simulate a dream sequence in time. It can also be used as fire in many different show applications; but when you need power, surprise or visual stimulation, it can take on the form of an industrial explosion, a distress signal flare from a lost ship at sea or a variety of fireworks both in and out of doors.

Once I have chosen the effects, I like to design around the lyrics of the songs. Listening to lyrics can help to create landscapes that perhaps even the musician may not have imagined. Two or more creative heads are better than one. The flow of lighting and all the effects used is very important since some performances can last up to three hours or more. As a designer, you must learn to hold back on your effects and use them sparingly. Many of my lighting and visual effects are used only once per performance. This gives you the opportunity to improvise and create on-the-fly between songs. During a rock show that has 23 songs played over two hours, I will have at least one special effect per song, whether it be lighting, lasers, pyro or film. These effects will happen at the same place in the same song each night. In between these special effects exists the time I can be the lighting artist, creating at whim using the rest of the lighting system. This means that, although the special effects for each song will always be the same, the rest of each song changes from night to night. Most designers are not able to do this which is why, together with my own sense of musicianship, it is one of my fortes. I give the audience a fresh show constantly, especially for those who come to more than one show. Most designers rely on a computer to do this for them.

Once I have finished visualizing what I am about to create from the lyrics, I then know how to structure the show. Next, I design the truss configuration that will house the lighting and effects coupled together with soft goods (i.e., scrims, legs, curtains). Once the truss structure design is complete and the lamps and effects are drawn in, I then decide on circuitry and colour. Colour is a very important part of the way I design. I love the use of dramatic saturated colouration. This brings forth feelings in the music and visually emphasizes many of the creative moments. It can also exaggerate the other special effects happening simultaneously. Circuitry is vital in design. Here is where I must decide which lamps will illuminate at the same time pertaining to location in the truss and then, where it will appear on the lighting console. Once this is figured out (which can take many hours), I am then ready to blueprint the system.

Many people use computers to do the blueprinting. I presently work on an Apple computer and all my drawings are done with the ArchiCad program, giving me a three-dimensional look at what I have designed and how it will appear inside the venue.

Rehearsals

All of the above has still only been on paper for about two or three months before rehearsals begin. Rock tours usually allocate between two to three weeks for rehearsals while other kinds of shows can rehearse for months. This depends on the intricacies of the show. During the rehearsal stage, I will go into the arena for 16 hours a day. Groups will often rent the building where the tour will start out for rehearsal. The crew will take two complete days to set up and tech the system and make sure all the bits and pieces are not only working but also structurally sound; then I go to work translating my ideas into the computer lighting consoles. This takes a team of four people including myself. We take a live recording of the artist and spend the next 14 days programming two to three songs per night until the set is complete. Our programming time is usually from 8 p.m. to 11 a.m. This is when the designer has total freedom, since the artist and sound crew rehearse from 12 p.m. to 7 p.m. (when we sleep!).

Once we complete the programming, we run the show over and over until we are familiar with the cues. The team of four consists of one director, one designer, one programmer and one additional board operator to run colour changers and various moving fixtures. On many of my tours, I will be both director and designer, although most tours will have a director and the designer will leave once he/she is confident that the director is fully in control. It takes about two weeks before I am totally satisfied with the format of the show. After about 20 shows, everything is running to perfection. Now that everything is in working order, the tour begins and five shows per week for the next year will be in progress.

Directing the Show

Now the only thing left to do is run the show! This entails, depending on the size of the show, several different areas. Now that I have all the pieces in place, I am involved for the length of the show (anywhere from two to three hours per night) calling spot cues, laser cues, projector and pyro cues as well as running the console. Let me say that not everyone directs a show the way I do. Many directors like to let a computer take over a great deal of the tedious aspects of the direction; however, I like the direct, hands-on approach. I find that I have much more control over the subtlety in timing and can manually make corrections or cover without anyone noticing. Each of these different areas (i.e., spots, lasers, projectors and pyro) have inherent problems which can arise. Here are some you need to keep in mind:

Spots

Calling spot cues usually involves remembering the names of at least 12 IATSE (International Association of Technical Stage Employees) union workers who change on a nightly basis. So that you are not calling the name of the prior evening's spot operator, it's a good idea to produce a visual spot chart handy at your lighting console. This can sometimes be the most disappointing aspect of the show for a variety of reasons, namely, these individuals do the same job every time for different shows and can be less than enthusiastic about your show or the standards you like to uphold. Novices have trouble with timing and have been known to sometimes pick up the guitar tech for a solo rather than the artists. Seasoned veterans, on the other hand, sometimes like to sit in their chairs expecting two or three cues. Because I sometimes use spots to create part of a look, I may call 30 or more cues they are not expecting. I often hear them say that I've given them a good work-out. Some directors use computer-operated spots controlled from the console. I don't use this method for two reasons. One is that the look becomes very mechanical and does not have the element of subtlety. The other has to do with loss of control when the computer crashes.

Lasers

Lasers pose different kinds of challenges. Of first and foremost importance is laser safety, which is governed by the C.D.R.H. (Canadian Department of Radiological Health) or the B.R.H. (Bureau of Radio logical Health, in the U.S.) safety standards. You must have a sound understanding of these standards when you are designing, because it includes where you can and can't direct the beams (i.e., not into the crowd). Once you've designed your effects, you may find that during the show's set changes, mirrors may have been moved. Stage hands can sometimes bump into the mirrors or projection table. A forklift could drive over the hoses cutting off the water supply which automatically shuts down the lasers. If you're doing an outdoor show in colder climates, you may need to worry about your water supply freezing.

Projections Video and Film

Aside from the general trauma of a projector breaking down or a film breaking or burning during the show, a consideration you need to think or know about includes utilizing time-code devices. This requires the musicians to wear headsets through which they can hear the monitoring tones (beeps or clicks). This allows the film and music to be in sync. Musicians usually consider this somewhat of a distraction. The alternative is to roll the film on musical cues which entails allowing time for the system to ramp up. This takes anywhere between four to eight seconds before cues actually come down. There can also be projectionist errors, the most disconcerting being bad lining up of sync points recognize this when lips on the screen are ahead or behind what the singer is producing on stage - looking like a badly dubbed foreign film. The most difficult aspects of using film involves keeping the film clean and balancing multiple projector brightness.

Pyro

Pyro can provide you with hundreds of choices ranging from flares, flames, gerbs, rockets, air bursts, low level smoke or cracked oil. It too, like lasers, requires special safety measures. In Canada, you require a safety officer and a licensed pyrotechnician. Pyro is governed by strict fire codes which are different in certain cities and states. California probably has the most stringent set of standards. It involves a three-year apprenticeship under a licensed motion picture pyrotechnician, letters of recommendation and sponsorship by five California technicians who use pyro on a weekly basis. James Hetfield of Metallica was recently seriously burned due to lack of awareness on both the part of the pyrotechnician and the artist. On Rush's "Counterparts" tour, an effect was cancelled by my safety officer after my calling a cue because Alex Lifeson was in a dangerous spot on stage.

The use of pyrotechnics in a show should be done tastefully. While everyone's idea of taste can be quite diverse, pyro, in my opinion, should be subtlety used to enhance aspects of the show - not distracting. Proper use can make or break a show. Placement and spacing of the effect (or any effect for that matter) should build as the show progresses.

The Console

The type of lighting sources as well as their functions will help direct you as to which console to choose. The A volite Diamond console, the See Factor Light Coordinator, the Vari*Lite Artisan and the Light and Sound Design Icon Control Desk are just a few from which to choose. Some boards run computerized rigging as well as pars and intelligent lighting. Many of these boards have DMX capabilities which gives the director versatility. The most difficult aspect of directing the show involves pacing and coordination of all the spots, lasers, projectors, pyro and props or extras (i.e., bunnies used in Rush's "Presto" Tour). The most important solution is to maintain your sense of cool, calm and professionalism, especially when your computer board goes down in the middle of a show.

In my shows, I take theatrical-effects lighting and combine it with standard rock-effects lighting. This, together with my avant-garde designed lighting effects results in a three-dimensional magic created by the controlled blending of colour, video/film, pyrotechnics, lasers and the newest diachronic intelligent lighting sources available today.

I've given you a glimpse of some of the essentials in designing lighting. For those of you just starting out, it has proven essential to have a background in electronics and computers. I also suggest that you try to obtain work with a local lighting company so you can obtain hands-on experience. You will probably do better than most if you have all of the above combined with a sense of musicianship and some theatrical training (beyond high school). Above all, have the willpower to tough it out in the beginning (don't let anyone tell you it's easy). You are the one who must make it happen - and that means the show as well as your career.

Each show I create will always be different and challenging but will also have my signature. If you can take what stimulates you (i.e., the changes of the seasons and combining it with natural light changes that happen during the day) add a variety of other stimuli and make it come alive, use technology to your advantage creatively and have a good memory for numbers, you could probably become a successful future lighting designer yourself.

HOWARD UNGERLEIDER HAS DESIGNED SHOWS FOR RUSH, ROD STEWART, DEF LEPPARD, QUEENSRYCHE, TESLA, KIM MITCHELL AND GOWAN. HE ALSO DESIGNS FOR FILMS, VIDEOS, TELEVISION, CORPORATE SHOWS AND ARCHITECTURAL STRUCTURES.