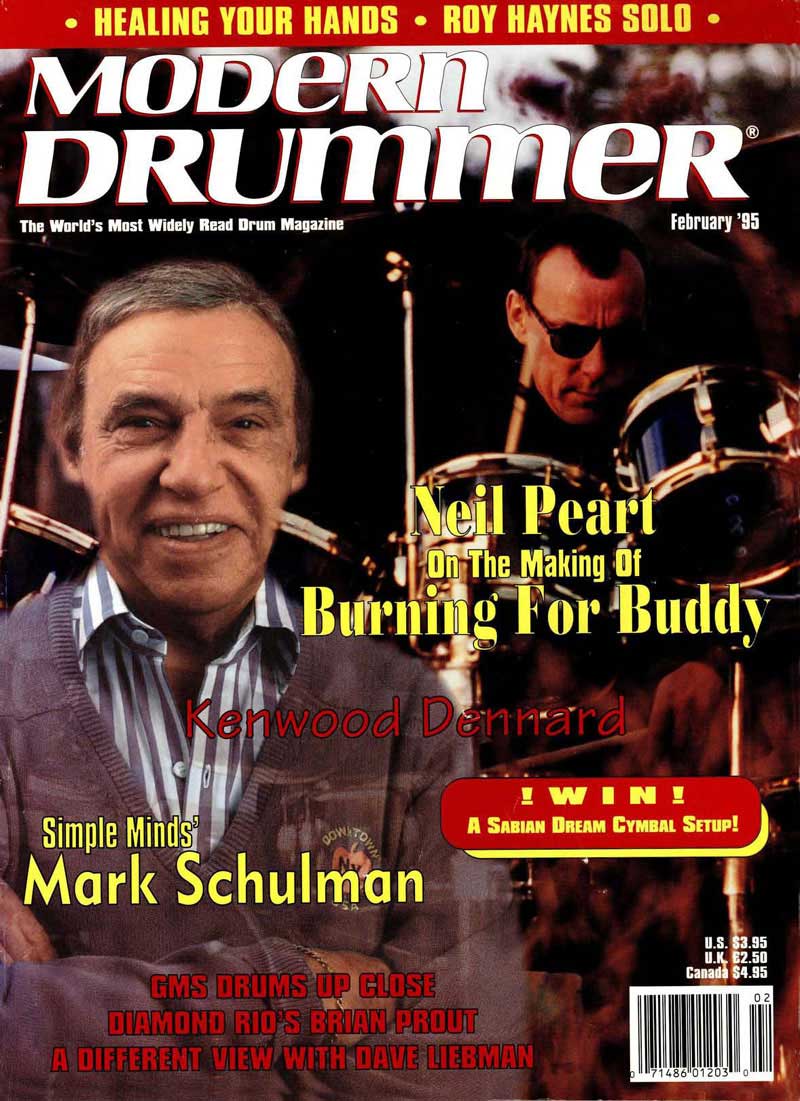

Walking In Big Shoes

Neil Peart On The Making Of Burning For Buddy

By William F. Miller, Modern Drummer, February 1995, transcribed by John Patuto

The place was electric. There was a palpable buzz in the air, a tension that caused your heart to race just a bit and your knees to feel slightly weak. Big-name drummers, musicians, music-industry types, journalists, photographers, engineers, crew members, and scattered hangers-on were all nervously milling about the studio. Everybody seemed to know that something special - maybe even historic - was happening.

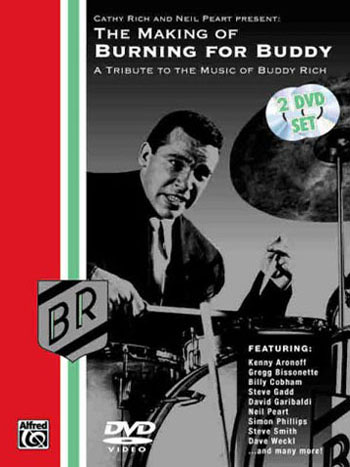

This past May the Power Station - one of Manhattan's famed recording studios - was the sight of the sessions for Burning For Buddy, Neil Peart's tribute to the music of Buddy Rich. The concept was simple: Record some of today's finest drummers playing Buddy's music with his big band. For two weeks straight an average of two drummers per day came into that studio, set up, ran down the tunes, and recorded. The pace was so quick that many of the drummers upon finishing their stint walked out of the studio asking, "What just happened here? What did I just play?"

At times the scene (especially in the control room) was a bit bizarre. After a take the entire band would file in, the eighteen or so musicians cramming into the small room. Peart would move to his ideal listening position, which involved him crouching on top of a table located between the monitors. As the group listened to the playback the given drummer seemed to be surrounded, with Neil looking down from his perch. And a framed photo of Buddy positioned against the studio glass certainly reminded everyone of the high standards that needed to be met. From a drummer's perspective it would be hard to imagine a more pressure-packed situation.

To successfully pull off an undertaking of this scope, Peart called on the expertise of several Rush employees and an engineer (Paul Northfield) he was confident could handle the task. Neil also did his usual "homework," taking months studying Buddy and his music. However, the demanding pace and high pressure of the session had some people wondering about the quality of what was being recorded: Did anything usable make it on to tape? But when the two weeks were up, Peart had thirty-nine completed pieces - some potential classics - of which seventeen made the album. (Neil is hopeful that follow-up volumes will be issued so all of the tracks will be available.)

As for the drummers selected, they're a veritable who's who of great players. (For a scorecard on the drummers see the "Participants" sidebar [below].) Peart, along with Cathy Rich (Buddy's daughter and the executive producer on the project), came up with the list and an idea of what tunes they wanted to record. According to Neil, "We wanted to honor the music of Buddy, make it presentable to a young and diverse audience, and do it in a way that best featured the different drummers."

As you listen to the disc you'll hear the trademark BR band sounds: a fiery intensity throughout the ensemble, an explosive horn section, dynamic and challenging arrangements, top-notch soloing. What's a bit different is the way the drummers put their individual stamp on the music. Buddy used to say that the drummers he admired had their own sound, and this record proves that each of the gentlemen involved certainly do have that: They bring out the beauty of the music with their own interpretations.

But a question on a lot of people's minds is, why Neil Peart? Why did a man who has earned a reputation as a skilled progressive rock drummer take on a project like this? Well, it seems that somewhere deep down inside of Neil, a love of big band music burns. He'll admit he's a rock drummer first, but there's something about big band. And it must be important to him to take on the sizeable musical and financial risks involved. (When you think about it, Peart might be the only drummer who has the record company and management clout, as well as the personal wealth, to be able to pull off an event of this magnitude.)

In any event, Burning For Buddy is one of those magical drumming moments that doesn't come around all that often. We should thank Neil for that.

Over the past six months you've listened to more Buddy Rich music than probably anybody ever has. Do you like Buddy's playing now more or less than when you started this whole thing?

Good question. I have to say I enjoy his playing infinitely more, and certainly, as you say, I've studied it in such depth. To prepare for this project I studied his playing, his arrangements, and more importantly how he approached the arrangements. I've listened to all sorts of tapes and watched literally hundreds of film and video clips of him.

With all of this study, was there anything about Buddy's music that surprised you when you actually sat down with the band and started going over the material?

Nearly everything. [laughs] In the larger sense I was surprised at how good the music was and how good the arrangements were when I got to know them better. In some cases, if the arrangements were more intricate, more complicated, they demanded more listening.

When I was in the studio with the band and they were doing a first run-through with a new drummer, I made a point to always go out into the room. There was a little corner where I could sit and hear all of the horns, feel the bass and piano from the rhythm section booth behind me, and be right in front of the drummer. I would close my eyes and it was all right there the way you're supposed to hear it. The power and the interplay was so nice.

Being in a room with all those musicians must have been a bit different from your "usual" trio.

But there was a similarity in that the big band had just as much power as a rock band - maybe more power. I think it was that power that largely attracted me to big band playing, and that's another thing that sounds so good when you're actually in the room. There's such a great feeling when you're hitting the shots with the band, pulling that trigger. It's a really powerful gun, the brass section. Buddy used to compare playing with a big band to driving a Ferrari and hitting the accelerator - just so much power. The music has that.

Another thing I really enjoy about Buddy's music is that it's very modern. As I mentioned in the liner notes. Buddy was not about nostalgia. He was always changing his repertoire, always wanting new arrangements, always getting new guys in the band. Consequently, his music changed so much. From the late '40s right up until he died, he kept changing and growing.

Were you a big fan of Buddy's early on in your development?

I have to admit I hadn't been a fanatic about Buddy at all. That's perhaps another irony. I never got the chance to meet him, and what's even odder is that I never saw him play live. As a teenager I saw him play on television several times, but I wasn't a fanatic. I was an admirer - I guess that would be the right term. I always knew he was the best and I respected that. Unfortunately at that time my tastes seemed to lay elsewhere.

So is this love of big band music a more recent development for you?

Actually, no. The big band thing was born through my father. Big band was his favorite music, so I heard a lot of it. When I got interested in drumming, I heard his music and what the drummers were doing, so I was aware of it.

I remember you telling me that since that music was what your father listened to, you seemed to rebel against it.

I did that in so far as what I wanted to play, but I did enjoy listening to it. I got interested in Duke Ellington's music and Count Basie's music. I started buying those records in my teens. I started buying Sinatra records then, too.

When I lived in England I went to see Tony Bennett at the London Palladium when I was eighteen, by choice, and loved the man. Kenny Clare was playing drums for him then. That was a case where age and generation didn't matter. Kenny Clare was one of the most exciting drummers I ever saw. Many of the big band drummers were like that. Sonny Payne had that quality. And obviously, Gene Krupa too. You couldn't help but be excited by them if you were a young drummer regardless of style or preference.

So I think it came around full circle for me, when, in 1991, Buddy's daughter, Cathy, asked me to perform with the big band for the scholarship show. While I was very intimidated by it, it sounded like an enormous challenge and an opportunity to actually play some of this music I loved. I went into that experience for that reason, basically as a good way to challenge myself. I hate when things get too safe.

But what led you from that point to getting so involved in a much larger project like Burning?

Actually, to be perfectly honest, all I wanted was a very selfish thing - the chance to play big band music again! In my darkest little mean heart of hearts all I wanted was to feel the excitement of kicking a big band, I wished somebody would make a record so I could have the opportunity to play with Buddy's band again under more controlled circumstances than a live concert, and I guess I realized I was the one to do it! That truly was the germ of the whole thing.

And you felt equipped to take on the project?

Honestly, no. There was just so much learning to do, and I did a lot of it along the way. I couldn't sit down with the band on day one and give them a speech and say, "This is how it's going to be. Here's how we're going to work. Here's what I expect from you. Here's what you can expect from me." All of that had to be felt out step-by-step.

While this was my first official project as a producer, I have worked with many good producers over the years and I do have some experience! [laughs] I think I've learned what a musician wants to have from a producer. I decided on my basic role in my own mind: I had to be a facilitator and make it easy for people to work, and I had to be a motivater - get them working, that sort of thing.

Was there any particular producer you modeled yourself after?

I've learned from many of the producers that Rush has worked with over the years. I think an important lesson I learned from Peter Collins - a producer we've worked with on three of our records - is that a producer doesn't need to be overly concerned with certain things. Peter always stays away from the technical side of making records. He leaves the sound to the engineer and to the musicians. He even leaves the details of the performance to the musicians - they can worry about it and quibble about it with the engineer and the other musicians. As a producer he's just listening to the song and the total picture of what's going on. I decided that's the right way to go for this project.

So you didn't have comments for drummers after they made a take?

I did, but only in so far as how what they played affected the arrangement - did it help to get the song across? Unfortunately, what that meant was that I couldn't take advantage of all those free drum lessons and tips I could have picked up had I just focused on what the drumrners were playing!

Basically all of the musicians were producing themselves. I expected them to critique their own parts and know if they could live with it or not. I couldn't sit there and listen to the whole piece of music plus fifteen separate parts in every nuance and detail. So it quickly became apparent that that couldn't be part of the job.

The first thing I would do after a take was to ask everybody, "How did you feel about it?" Then if someone said, "made a mistake in bar 43," "Good, let's listen to the take and see if the rest of it is acceptable and if we can fix that one part." I counted on everybody there to critique themselves, and I was told that the musicians were not used to being worked with in that way. Some of them said that after all these years it's nice that somebody is asking their opinion of their work. The by-product of that was that everybody started to feel a certain responsibility to the project, everybody wanted it to be as good as they could make it.

I understand the pace of recording was very fast.

Yes. We had two weeks to record a lot of music. We were recording two drummers a day, and I jokingly told everybody that they had a four-take maximum. Most of the drummers nailed the parts fast. I think working that way added a certain spark to the music. Every track is alive and full of energy.

Everything had its adventure. Every song started new and every drummer that came through the door was a new starting point. We had to set up the drummer's gear, get sounds quickly, and go. Everything happened so fast. That was the astonishing part. The day we recorded Simon Phillips, we did three songs with him, and that was after doing two with somebody else. We recorded five tunes that day, and at the end of the day I couldn't remember who we started with that morning. I think that happened because we had to pour all of our concentration so totally into each song. The world began and ended at that point.

I would imagine that the level of stress you were going through during those two weeks was incredible.

It was intensely stressful. It really was. The level of concentration that it took, the level of focus that it took, the discipline.... We were invited out every night to check out other players in New York. All the musicians working in town would say, "Come on down and see us tonight." But I couldn't because we were starting 9:00 every morning and I had to be my absolute sharpest.

How did you decide on the drummers you wanted to include?

I had a list of people in mind of players who are my favorite drummers. And Cathy recommended people she had worked with on other Buddy Rich Memorial concerts. Obviously, we also wanted some of the legendary figures, some of Buddy's peers, like Joe Morello and Ed Shaughnessy. I was disappointed that Louie Bellson couldn't make it, but unfortunately he was in Europe at the time. Vinnie Colaiuta was another drummer I really wanted to include because he had been so good with the band on one of the previous scholarship concerts. Unfortunately, he was in Europe at the time. There were a couple of schedule conflicts that kept a few people from participating.

We had a two-week window we had to record in - if people couldn't come through that window, then we had to miss them. Even at that, in those two weeks we recorded over three hours of music! That's why the first CD has seventy-six minutes crammed on it. I wanted to get as much on as I could, not only for its own sake, but also because I have all this other great material still waiting to be released.

How did you decide on the tunes to be recorded and which drummers would record them?

Actually, Cathy and her husband, Steve Arnold, had a great deal to do with that. They both know Buddy's music very well. Cathy and Steve's intimacy with the repertoire was invaluable. In some cases we chose a tune based on the availability of the music, the style, and how it would work with a certain drummer. And if a drummer requested a particular piece, we tried to accommodate him.

For instance, when I was asked to do the scholarship show, I was looking for a fast and a slow swing tune. They sent me about eight or ten different tunes from which I picked "Cotton Tail" and "One O'clock Jump," because they were the type of traditional things I really wanted to try myself on. Other drummers took the same route, where they just asked for some suggestions based on style and then chose from there.

Were there any specific things you picked up from some of the other drummers who participated?

Being exposed to so much great playing over the two weeks was extremely inspiring. So much was played that I'm sure some of it stuck with me. But I do remember specifically trying to find out more about playing big band drumming. I tried to speak with the drummers who had that experience. Ed Shaughnessy and I had dinner one night, and I picked his brains about the music and about how a lot of the older guys played.

It was very interesting to me to watch the way Ed played, actually. I liked it. He took a looser approach because of his confidence with the music. He was so comfortable with the style that he had a more relaxed feel than I think a lot of us less-experienced big band guys hoped to have. I liked the way he was able to be very precise and very considerate about what he played and where.

We talked about time keeping in a big band sense. In the middle of "Shawnee," one of the tunes he recorded, there is a little fanfare section where he pulled the time way back. If he had continued the time through that section it would have sounded awful. It proved that metronomes and drum machines don't apply to this kind of music. It has to be felt by the drummer, controlled by the drummer. The time can't be allowed to speed up or slow down. The drummer has to be in full control of the time. But there are instances when you have to "shade the edges" of time for the sake of the music. That's where the sheer level of skill can be astonishing, and I learned that from certain drummers on this project.

You mentioned that there were minimal edits made to the tracks, although you would pull a solo section from one take and stick it in another take if that one was superior. The question I have is, when you're actually lifting sections and the drummers are not playing to a click, how can the sections from different takes be in time with each other?

Believe it or not, it wasn't a problem with any of these drummers. Any of the edits we made involved whole sections. We couldn't just take a solo, for example, because of all the background spilling.

But for the drummers to be so accurate with the time among a few different takes is amazing.

That's a testament to the quality of these players. Any time we needed to repair a take, for any reason, to get a better solo, a different drum break, or a major chunk of the tune, we were surprised at how in time everything was. These guys were that in control of the time; they were all that good.

It's like Buddy always said: If you're a good drummer you should be able to play all styles, that if you're a good jazz drummer you should be able to play rock and vice versa. It's true, as Kenny Aronoff and I both found. We both had little experience playing jazz. We both put a lot of time and research into finding out how to go about it, getting people to help us, rehearsing it, preparing for it, and - I think I can say, at least in his case - turning in a really credible job of it. It's proof of what Buddy said.

How do you think Buddy would have felt about this whole project?

Well, not knowing the man, it's hard to say. But everyone's telling me he'd be beaming. We did a good job on his music, everybody played well, and the spirit of the whole occasion was great. So many of his friends and colleagues came together to honor him for what he did for music and for our instrument. Attention is being paid.

The Participants

As the main instigator and producer of Burning For Buddy, Neil Peart had the unique position of being "behind the glass" while several of today's finest drummers recorded for him. Here are his thoughts on their musical contributions.

Simon Phillips

"Simon was incredibly meticulous, very professional, and prepared. He came in with his own charts, and he had his own ideas of how the songs should be performed. He introduced dynamics in to the arrangements that weren't there previously, which was also a nice touch.

"I requested that he do 'Dancing Men' because I knew he'd do a great job with it, and it was the track I wanted to open the album with. He nailed it almost immediately - and that arrangement is challenging. Simon wanted to record 'Good-Bye Yesterday,' so he did that, too.

"Simon had also prepared 'Norwegian Wood,' so even though it was late in the day, we thought we'd try to get a take. I was concerned because most of the guys in the band had gigs at night - doing Broadway shows like Damn Yankees, Crazy For You, and Kiss Of The Spider Woman. So at the very last point of a very tiring day, Simon and the whole band did a beautiful job on 'Norwegian Wood.' Simon played brilliantly. He's known for his tremendous technique, but he actually impressed me even more with his musicality. I can understand why he's achieved the high status he has."

Dave Weckl

"Dave has a very methodical way of working, and he's very self critical. He knew when he had to pull back the tempo or push it a bit. He had beautiful-sounding drums and cymbals and a very musical approach to his instrument.

"Dave told me a good story about one of the tunes he recorded. 'Time Check.' When he was sixteen years old he used to play along with that song. He used to take his parents' stereo and slow the turntable down to learn the part, so the song had a special emotional appeal for him. He gave a knockout performance on it. Although it isn't on the first release, it will be on the next. But 'Time Check' was the song that had a special place in his heart, and that's such a common image for any drummer to take a turntable or tape player and slow down the tune to figure out what's being played. I think everybody's been through that."

Steve Gadd

"A lot of people might be surprised to hear that he was nervous about the session. I greeted him and asked how he was, and he said, 'I'll be so glad when this is over.' I thought to myself, why should you be nervous? You're Steve Gadd! His version of 'Love For Sale' has become my favorite of everything we recorded. I just loved the feel he created. Plus, the solos that the different musicians played on it were superb.

Steve was self-critical in the same way that Dave was. He was very critical of what he was doing and how it should be, and he wanted to go back and do it again - I had to stop him and say, 'Look, it's beautiful. Stop now.' He was someone who exemplifies the quote I once heard, 'No art is ever finished, it's only abandoned.' He demands so much of himself, and consequently was tending to sense flaws when there were none, where the time was perfect and his execution flawless."

Steve Smith

"Steve was one of the few guys who I had met before. I've known him for a few years now, and it's been a thrill to see how he's developed as a player. He just knocked all of us over with his musicality, his precision, and just how far he has taken his craft over the years. He is a master drummer. It's a beautiful thing to see someone in possession of such a high level of mastery that he is enjoying right now. He's earned it. It's just inspirational to see what he has done.

"I think what is really astounding about Steve is that his abilities go a lot deeper than sheer technique. He has a musical sense to his playing that really elevates the music. You can certainly hear it on the track on the first release, 'Nutville.' Steve played great with the band, and he certainly inspired me!"

Matt Sorum

"Matt was just a total joy to work with. As far as I'm concerned he's a prince among men. Matt was so excited to be there, and he seemed so thrilled to hear himself with that band - he really kicked them. After one of the takes one of the horn players called out, "Hey, who is this guy?" And Matt stood up, struck a pose, and said, 'I'm the heavy-metal guy.' He had a great sense of humor.

"The following day he sent over three big trays of fruit and cheese, two cases of Heineken for the band, a bottle of scotch for me, and a bottle of champagne for Cathy Rich, plus he sent notes to everybody. He was just so grateful and he expressed his gratefulness so beautifully. It was a really nice thing to do."

Manu Katché

"Manu surprised me. I've always loved his playing, and he was somebody I really wanted to have for this project. I think he's a real ground-breaker. I thought I had a pretty good idea how he played, but I was wrong! You should hear the drum solo that he played on 'No Jive' - it's insane. I couldn't believe it. It's weird and yet it's perfect. When he's playing for someone else he plays in supportive and very fluid way. So when he played this solo he surprised me.

"Manu played on the session with percussionist Mino Cinelu. They knew each other and had worked together before; they did a lot of their conversing in French. They were both just so personable and so soulful as people and as players. Everybody remarked that there seemed to be a warm glow in the room while those two were working. In both of their cases their playing is certainly very warm, and their hearts are too."

Billy Cobham

"Bill is such a consummate professional, and I have to say I'm indebted to him. He recorded on one of the last days of the session. At that point there were a few tunes that I really wanted to have recorded, and without even knowing the arrangements he came in and did them. In Buddy's band, as you know, there were no drum charts, so Bill used the lead trumpet part as his guide, and he sight-read the tracks. Everyone thinks of him as a great technician, but he's also a skilled reader. I joked with him that I really appreciated his 'taking requests.'

"Bill was very interpretive in his style, which really interests me. His style is so seemingly unstructured. It's so contrary to the way that I think. He's happy to try any number of different ways of approaching a tune. I found that to be very interesting."

Rod Morgenstein

"I've known Rod for years, and he's a favorite of mine as a player and as a person. He was nervous about doing it, like the rest of us were, but he came in and did a good job very quickly. He was really well-prepared.

"The tune we originally sent him. 'Good News,' is a really long piece. After he received it he called me up and said, "This piece is eleven minutes long. Are you sure you want me to do this one?' I got worried, but I had the record of Buddy's version, so I listened to it. I felt it was such a great piece of music that I had to say to Rod, 'Go ahead, but we'll have to record something shorter too.' I got him to do 'Machine' as well, which is another tune that I really liked. And as expected, he did a great job."

Max Roach

"Max didn't want to record with the band, so we thought that we'd have him play some of his solo pieces. I told him the story about 'The Drum Also Waltzes,' that it had been passed on to me by another drummer. I was doing it in my current solo and Steve Smith was using it as a clinic exercise to teach people. It seemed to please Max that an idea of his had survived and continued to instruct new generations of drummers.

"When he recorded he was the only one there; the band wasn't around. We had the lights softened. Before he began his piece he would wait for our cue. He'd have his sticks raised, and after we gave him the go-ahead, he'd take a few more seconds and then begin. It was a beautiful moment and Max approached his playing with so much dignity. I was very impressed with his respect for the drums.

"The hard thing for me was choosing how to present these solo pieces on the album. I didn't want this to be a totally drum-focused record with lots of solos because I didn't want to alienate any listeners. But I actually got the idea for the solution from a Brazilian record I have that has a little percussion interlude that just weaves in and out from time to time. I always thought that was a nice idea. "The piece creates a very hypnotic feel - just a quiet, repetitive pattern. It's almost like a heartbeat. And due to a slight accident that happened during the mixing stages - where a lengthy delay was applied to the solo - the hypnotic effect is even enhanced. The effect worked so well, we ended up keeping it. I was very happy with the way it turned out."

Kenny Aronoff

"Kenny is such an energetic person, and he came in and just delivered on his two tunes. He and I had a bit in common because we're both known as rock drummers, and while he has training in other areas of percussion, he makes his living playing rock 'n' roll drums. We both challenged ourselves by playing tunes that were more jazz-leaning, and I was really thrilled to hear how Kenny interpreted his tunes.

"I love the job he did on 'Straight No Chaser.' It is so powerful and punchy. To me it's obviously a rock drummer playing in terms of its weight and even some of the figures he used, but it worked. We kidded each other when we were listening back to the tracks, pointing and shouting 'Rock! Rock!' when we heard a fill or figure that was more like something a rock drummer would play.

"Kenny also helped me add percussion to one of the other tracks, 'Pick Up The Pieces.' That happened when I was mixing the track in Montreal and Kenny just happened to be in town doing some session work. He called to say he was in the area, so I invited him over. We had a lot of fun overdubbing the percussion parts during the drum break in 'Pieces.' It was actually a great opportunity for the two of us to work together as drummers with nobody else there. That was a particularly enjoyable experience for me. We called ourselves the 'bald bongo brothers.'"

Omar Hakim

"Omar and I first met at the Buddy Rich scholarship concert in '91. He is one of those people who I felt an immediate affinity for. I love his playing - the fluidity of it. It's smooth and yet it has a snappy excitement to it, and he plays with such a good feel.

"'Slo-Funk' was the tune that I think he had done at the scholarship concert and the one so well-suited to his style. He came in and did an excellent job on it. Unfortunately, he was very uncomfortable with the rented drumkit he had sent to the session - he never seemed satisfied with it. He ended up deciding not to record the other track he had prepared, but I was very happy to have him do the one tune."

Joe Morello

"I always tried to go out into the room when a drummer first played through a tune with the band, just so I could get an idea what their drums sounded like acoustically. It was very interesting to hear the fire in Joe's playing in the room. When he booted that bass drum, boy, it was booted. His touch and control are such that there is tremendous restraint to his playing - a very refined approach - and the dynamic range of it is generally low, physically low off the head and also low in terms of volume. But when he does give a little snap of the wrist or a little extra 'oomph' on the cymbal, you're aware of it.

"When he first came in I didn't expect a very energetic performance from him; he was kind of stooped and slow-moving, and he kept saying, 'It's too early in the day to play.' But when he was behind his drums he was committed to his performance. There was so much fire in his playing, and that was inspirational to see a guy just sit down and deliver the goods. We captured a bit of history with him."

Bill Bruford

"Bill brought in an original piece - 'Lingo' - which was a real challenge for the band, It was a very polyrhythmic piece quite different from what we'd been doing, but I was happy to see the commitment the band put into learning the song quickly. Bill made the remark, 'They could have ruined this for me.' Everyone poured themselves into that piece and made it happen. It's a special piece because it has the flavor of the band, yet it's rhythmically and structurally more adventurous, which goes to Bill's compositional roots. That was an interesting piece to see go down.

"Bill also came in very well-prepared for 'Willow Crest,' a piece from Buddy's book. He had written out a basic chart of it for himself. Again, like so many of us, he was nervous about it but at the same time very concerned. He came in with a total commitment to make his time there the most valuable it could be for the whole project as well as for himself."

Marvin "Smitty" Smith

"'Smitty' is a born master drummer - it's unbelievable how good he is. But he's also a great personality - really cheery, sprightly, and happy. He's happy behind his drums, he's happy when he's not behind his drums. He's a good influence and he was actually around for a few of the other days when he wasn't recording; he was always a ray of sunshine to be around.

"To give you an idea how impressive his playing was, he recorded both of his songs on first takes. He was obviously very easy for the band to play with because his playing was so smooth, so consistent, so rooted in that style of music - it made it easy for everybody to lock in. So all respect to his ability as a drummer and as a person."

Steve Ferrone

"Steve is a real character. I've admired his work for a long time. I actually met him almost twenty years ago when he was with Brian Auger's group. Rush's tour manager had previously worked with Brian Auger, so we met somewhere socially all that time ago. I followed his work, especially the work he did on the Bryan Ferry record last year, and I've really admired what he's done.

"I wanted him to come in and play 'Keep The Customer Satisfied,' which he did, but he also brought in an arrangement of 'Pick Up The Pieces,' obviously a tune he's known for from his Average White Band days. It was an arrangement written for full big band by Arif Mardin for a jazz festival Steve played years ago. It really shows Steve's ability to play with a great feel.

"Steve's another one of those drummers who is so casual and so comfortable with what he does - no tension, no self-consciousness - just walks in, sits down, and delivers."

Ed Shaughnessy

"Ed was kind of a guru figure for me. He's a master at this style of music, and I was very excited to have him play with the band. I learned a lot from watching him work.

'Ed's such a comfortable man - comfortable with himself, comfortable with the world - very easygoing. But when he got down to work he took on a whole different focus - way more serious, more resilient, less humorous, and more demanding. He actually was the first drummer to record for the session, which was fortunate for us because he took control of the band and got things off to an excellent start.

"Ed recorded 'Shawnee' and 'Mr. Humble.' 'Mr. Humble' was a tune I guess he had written for Buddy. Whenever Buddy appeared on the Tonight Show they'd do this thing called 'Mr. Humble,' because Ed always said whenever Buddy came in Johnny Carson would say, 'Here's Mr. Humble.' And Buddy would say, 'Hey, when you're the greatest, what do you have to be humble about?'"