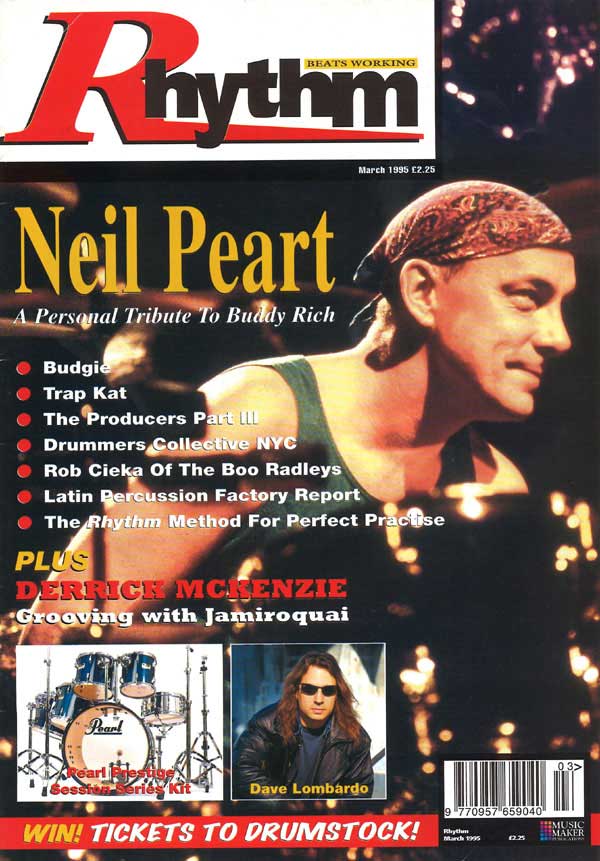

Rush Strokes: A Personal Tribute to Buddy Rich

By Chris Welch, Rhythm, March 1995, transcribed by John Patuto

Neil Peart is possibly the most slavishly adored drummer in the world, with legions of fanatical followers. Never one to abuse his power, he has instead used it for the good of humanity assembling the world's best players in tribute to the late great Buddy Rich. Chris Welch speaks to Neil about the Burning For Buddy project.

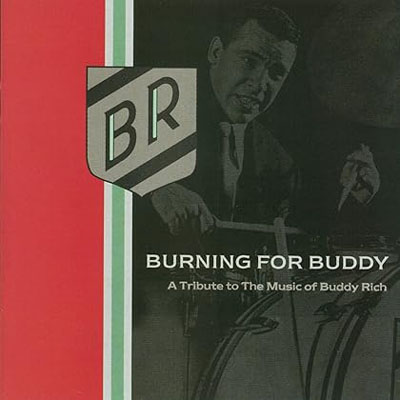

Burning sticks blazed forth a thunderous tattoo in tribute to Buddy Rich at a unique gathering of the world's top drummers last year. Simon Phillips, Max Roach, Steve Gadd and Bill Bruford were just some of the great players who came together in a New York recording studio to play on the album Burning for Buddy - A Tribute to The Music Of Buddy Rich (Atlantic).

It all happened last summer under the aegis of Neil Peart, Rush's renowned drummer, who came up with the excellent idea of recording a tribute album to the memory of the legendary Bernard 'Buddy' Rich. The result was a series of unique performances by Buddy's original 15-piece band back by guest star sticksmen. They played a whole range of arrangements and styles, from swing to latin, rock, funk and fusion, reflecting the kind of varied music the Rich band played right up until Buddy's death in 1987.

Such a tribute could have been a disaster. The art of recording big bands got lost somewhere in the '60s and the sound might have been dreadful. The choice of drummers could conceivably have resulted in hamfisted bungling in a vain attempt to revive the swing era. Instead, what we got was a collection of sharp and dynamic recordings, better than any cut by a big band in years, and drumming performances that roared with authority and carried the personal stamp of each individual player.

Burning For Buddy was recorded over two weeks at the Power Station in New York, sometimes with two drummers playing up to five tunes a day. It was all done 'off the floor' with very few overdubs.

"Although Buddy Rich was justly celebrated for his fiery drum solos," says Neil, "he was also known for his exciting ensemble work. The arrangements he commissioned for his big band were designed to showcase the songs and the band - not just the drums alone - and that's what we set out to do with this tribute."

Most of the musicians in the big band, including tenor player Steve Marcus, were veterans of the original Rich band. They were frequent visitors to Britain, and their annual seasons at London's Ronnie Scott's Club were eagerly awaited events, not least for a chance to hear Rich's acerbic wit, as well as the band's storming performances of 'West Side Story' powered by Buddy's astonishing drive. There's no doubt BR would have been delighted to hear the quality of recording and the attacking performances on the Tribute CD.

Among the standout performances are Simon Phillips' joyful romp through 'Dancing Men,' Steve Gadd's spirited 'Love For Sale,' Steve Smith's 'Nutville,' and Bill Bruford's own 'Lingo'. Neil Peart himself contributes a straight ahead swing version of 'Cottontail'.

Although Peart never saw Rich play live, he has taken an increasing interest in the legendary drummer's big band music in recent years, filling in the gaps in his knowledge. He had begun to feature sampled big band sounds during his spectacular showpiece solos at Rush concerts. But he found playing with a real acoustic big band, a different ball game.

Talking to Neil about the making of the Tribute CD, I asked how much he'd been influenced by Rich. "My only real exposure to him was watching him on television. Growing up as a young rock wannabe, I was pretty much rooted in that. I set my aspirations within reach and consequently Buddy Rich was always outside of that. I did always consider him the best drummer in the world, but playing like him was an unattainable goal. The biggest influences on me were drummers like Billy Cobham; I could learn from him and adapt what he was doing to my own playing. I kept Buddy on a pedestal since my first drum lesson, but I didn't have him as an influence. Not like Dave WeckI, who told me that as a teenager he played Buddy's records on his parents' stereo, slowed down to 16 rpm so he could learn what Buddy played."

Neil grew up listening to his father's big band records but rejected jazz and swing music. "Rock was my destiny. It wasn't until I lived in England at the age of 18 and felt more independent that I could buy Duke Ellington records. I remember going to see Tony Bennett at the Palladium with Kenny Clare playing drums and loving it. I wasn't close minded, but I still had to forge my own identity. In 1971 I could have gone to see Buddy at Ronnie Scott's, and it's a shame it was an opportunity lost. Now, later in life, I know his family so well, I feel certain we would have got along well".

Neil first played with the Buddy Rich Orchestra in 1991 at the Scholarship Memorial concert, at the behest of Buddy's daughter Cathy. It was a difficult but exciting challenge that he couldn't turn down. Unfortunately the gig was marred for Neil when dodgy monitor speakers meant he couldn't actually hear most of what the band was playing. He felt down and frustrated about his performance but was determined to try again.

Neil spent some time with New York teacher Freddie Gruber, who gave him greater insight into the subtleties and complexities of playing big band music.

"He was a contemporary of Buddy's and played in a big band in the '40s with Charlie Parker. Since then he's taught a lot of guys, like Ian Wallace and Steve Smith. When I heard Steve Smith play I was so knocked out at the progress he'd made in the last few years, I asked him his secret. He said: 'Freddie'. That was enough of a hint for me and I spent a week in New York with Freddie and completely rebuilt my drumming from the ground up. I feel like I've started over as a beginner. To be honest, when I first came into this music, I bluffed my way through it. I sat down and rehearsed every day for months for that concert in 1991 and again before making this record. I spent a lot of time preparing but was not armed with real understanding. I was coming at it with enthusiasm but, as I say, I was bluffing. Now I'm calling my own bluff. Nowadays, when you have to work with sequencers and click tracks there's no room for approximation. I play with the hi-hat firmly rooted, for instance; when you're working with two bass drums in a rock band, you learn not to be a slave to the hi-hat. I've gone back to the basics - Now I am a slave to the hi-hat on two and four. It changes the structure of time, which is a real interesting discovery for me."

In January 1994 Peart realised that with Rush off the road for a while, he would have time to work on the Rich project. "I had a chunk of time to do what I pleased and I thought it would be nice if someone did a tribute record that I could play on. I got hold of Cathy and she was intrigued by the idea. She and her husband Steve Arnold, who's also a drummer, had a lot to do with putting it together; they both know Buddy's music so intimately. They helped in choosing the material. Cathy had been involved in a lot of the drummers through the Scholarship Shows, she'd done about seven of them and a lot of the drummers I suggested she would either yea or nay, depending on the experience she'd had working with them before. We put together around 20 drummers we liked as people as well as musicians."

The final list that appears on the first CD is full of surprises, including some drummers you might not expect to be involved, and a few notable omissions.

Explains Peart: "We wanted some of the old timers, of course. Louis Bellson, for example, agreed to do it but was busy in Europe at the time. I wanted Vinnie Colaiuta and Terry Bozzio too, but they weren't available. I wanted Simon Phillips and Bill Bruford because I knew they'd be good in this context. Another one I wanted was Phil Collins, and I chased him for months. Finally I got a day when he was home and sent him a fax. He sent me a very nice reply, but he was in the middle of a tour and had to bow out. I thought he would have been very interesting playing with the band. But Marvin 'Smitty' Smith, who had worked with Cathy before, was up for it, and Steve Gadd. Gregg Bissonette, who didn't make it onto the first CD was at the sessions, and he had previous experience with the Maynard Ferguson Band. He plays this music so beautifully and comfortably; he was a natural."

What about Carl Palmer? He was a Buddy Rich fan from way back. "Um, it just got so difficult with the list. You can imagine how many people went on there. For me, the best representatives of that particular era were Bill Bruford and Phil Collins. Bill was the representative of that school, in a painterly sort of way."

The production on the album is excellent and the sound quality is much better than Buddy ever achieved on his big band albums in the '70s. "Well, Buddy was up against the obstacle of being completely ignored by his record company. The reason why so many of his albums were recorded 'live' was because it was convenient; it wasn't the leader's choice. Buddy didn't say, 'Oh let's record live in a bar.' Record companies just weren't interested in a jazz artist who sold at most 20,000 copies. We had the advantage of having a studio. Buddy himself was so open to changes and fresh ways of doing things it steered him wrong sometimes. In the 70's he was working with engineers who wanted to put damping on the drums and take the bottom heads off. Buddy tried these things, but they really didn't sound good. We spent time choosing a good studio and recorded the band in an open room so they were all facing each other. We used an old British Neve console to capture a real live sound. We didn't have to fiddle with the kits either, because we had many of the best drummers in the world and their drum sets tended to sound good, y'know? The mikes went on and the tapes rolled!"

There are actually three CDs worth of material from the sessions, and the first volume is what Neil considered to be the most successful and appealing to prospective listeners. "I didn't want this restricted to being a drummer's record by any means. I was tough on the drummers, minimising the solos. Some people came in expecting to play long solos, but I wanted to present the music because I love the arrangements. I didn't want to scare away non-drummers. There are drum breaks, but just a few bars. Joe Morello gets a nice little shot in there and Steve Smith has a very melodic drum break. Cathy suggested we include Matt Sorum from Guns N' Roses. His background is in studio work, so we knew he had to be good. He was the West Coast equivalent of Simon Phillips. When you wanted a good job done quickly, he was the guy you'd call. There were rocky tunes in Buddy's songbook, so that helped a lot in matching the drummers to the right material. I wanted to go into deep swing, while others wanted to stay closer to their own style."

Was sight reading required on the sessions?

"Everybody took it their own way. There are no drum charts because Buddy didn't read. That was kinda funny. Some just read straight off the lead trumpet chart, like Billy Cobham and Smitty Smith. Guys like Bill Bruford and Simon Phillips just wrote their own and Kenny Aronoff made up his own short form notation . Me and Matt Sorum just learned the piece and played by ear, which is the way Buddy did it. In fact it gives you fresh appreciation for Buddy because he knew hundreds of these pieces by heart. The band would play it once for him and he would sit down and play it with them. If there was a drum break written, all the horns players' charts would say was 'Watch Buddy.'"

When it was Peart's turn to play with the band he told the trumpet players, "Watch me!"

Of all the drummers playing on the CD, perhaps the one who comes closest to the spirit of BR's playing is Simon Phillips on his intro to 'Dancing Men'.

"Yeah, I guess, but he goes much further and busier than Buddy ever would. It's funny how Buddy is perceived sometimes. His playing behind vocalists, for example, is unparalleled. He could be totally invisible. I have records of him backing Mel Torme and Sammy Davis Jnr. and he was such a sympathetic accompanist, an art he'd learnt years before with Frank Sinatra in Tommy Dorsey's band. Nat King Cole would pick Buddy for his small groups because he was good at playing that style. Sure, he had to pull the trigger with a big band, but he could also be supportive in other capacities, and you can't say he ever overplayed. Since Buddy's time, drumming has become much more exhibitionist, especially in jazz fusion. The joke was that people were getting paid by the note, but that's not Buddy's background and in many of the tunes on the CD there were no breaks. I've seen videos of his concerts, where he'd only play perhaps one drum solo in a two hour show. He loved to lock in with the band and play; it wasn't all about solo drums.

What I love about big-band music is that it's a team effort, and that's what I love about Rush too. It's the structure and architecture but the musicians do have a lot of freedom. 'Love For Sale' is a classic big band arrangement which I play every day, either Steve Gadd's version or myself playing along with Buddy's band. It's so artfully constructed and it can be so exciting."

Did Neil feel like he'd like to have his own big band after this experience?

"Ha, ha! I don't think I'd go that far. Having been a rock drummer for 30 years, I don't expect to change now, but I'd like do more big band stuff, sure. It's become part of my ongoing course of study, but I don't want to throwaway rock music."

Neil described the atmosphere during the sessions: "No pun intended but it was a very rich experience. Out in the lounge area by the studio all the drummers were hanging out, and many of them came back the next day to see how their friends were getting on. It was beautiful. I'd poke my head out of the control booth and see Bill Bruford talking to Smitty Smith, or I'd meet Steve Ferrone who I hadn't seen for 20 years."

Neil was especially pleased to see Joe Morello from the Dave Brubeck Quartet on the session. Joe was famed for his slick technique and intelligent solos.

"When I had my first drum lesson when I was 13 years old, there was a picture of Joe Morello pinned on the wall."

Recalling Rich's famed temper, I wondered if there were some drummers who didn't want to be associated with Buddy? "Despite Buddy's reputation, I think that's largely unfounded. If he could be snappish with strangers, he certainly wasn't with his friends. They loved him so much, it's moving. You might expect his family to love him, but all the musicians in his band who had to put hp with his legendary tantrums tell stories about that but laugh with so much affection. We've all heard about the tapes of Buddy chewing out the band, but I heard Max Roach saying to Joe Morello, 'Buddy was always a gentleman to me,' and that little statement was so moving."

Neil was referring to the famous secret recordings made on a band bus of Rich bawling out his musicians for various failings and misdemeanours.

"The tapes were going around the Rush road crew and everybody was laughing and saying, 'What an asshole this guy must be to work for,' but my reaction was quite different. The first time I listened to it, I felt sorry for Buddy. Here's a guy who is the best drummer in the world, he has to hire these guys fresh out of school because that's all he can afford, they all think they know everything, and here's Buddy travelling in a bus with a bad back and having to put up with these second rate musicians who think they are God's gift to music! The frustration would have been enormous, so my sympathies went out to him, even at the time when I didn't know a thing about him. I just sensed that. Buddy kept that band going, whatever it cost. He started that band up in the late '60s, which couldn't have been a worse time, and by sheer force of will he kept it going until the end of his life, which is an amazing accomplishment. He kept on going right through the disco-drenched '70s, into the '80s. On his deathbed he told Cathy that he wanted the band to keep working and to do whatever it took. He asked her to put the Scholarship Foundation together to help young drummers and to keep the music alive. There were only two pieces of music he didn't want anyone else to play: 'West Side Story,' and 'Channel One Suite'."

Neil has found a way around this problem however. "We took his original drum track from 'Channel One Suite' recorded in the '60s, re-recorded the band to it and then recorded a vocal track by Annie Ross which is a kind of biographical treatment of Buddy's life. We also kept his drum solo intact, so it'll be the only real drum solo in the project. That will appear on the next volume. We actually have enough material for two more, but it all depends on how well this one does and what sort of demand there is. 'Channel One Suite' has got to be the grand finale: it's an 11 minute piece recorded in 1966 and Buddy's drums sound beautiful."

Neil says that the projected second volume would contain more traditional Rich swing material, including a version of 'One O'Clock Jump', featuring himself; Steve Smith plays a version of John Coltrane's 'Moments Notice'; Bill Bruford plays 'Willowcrest' - another Rich arrangement from the '60s; Simon Phillips recorded a version of 'Norwegian Wood', the Lennon / McCartney song that was a Rich band favourite.

Surprisingly, Max Roach didn't play with the band, but contributed a brief solo to the first CD. Perhaps he wasn't in the mood for a big band bash?

Says Neil: "Everyone was given the option to play with the band or with a small group. Max just wanted to come in and record solo pieces. I was left at sea afterwards, wondering what I was going to do with them. I wanted the record to be as musical as possible and here I was with three five minute drum solos by Max Roach! In fact his piece 'The Drum Also Waltzes' has been adopted by all kinds of players as a warm-up piece. I first saw it played by Bill Bruford with Earthworks, and I had never actually seen Max play it. So when I told him this, he gave me a new version to put on the record."

There is a possibility they may present some of the music live at various jazz festivals this year. "It remains to be seen if collective schedules will permit it," says Neil. "The band sounds wonderful and should be brought back in front of people, because that's where it really comes to life."

Meanwhile Neil has been so inspired by his contact with the big band world of Buddy Rich that he has started practising again for two hours every day. "I'm like a beginner, starting all over again."