Into Africa

Two Weeks on the Road Through Sun-Parched Savanna and Medieval Villages

by Neil Peart

Maclean's, April 3, 1995

Neil Peart is drummer and lyricist for the rock group Rush. His taste for two-wheeled adventures developed during the band's concert tours, through the daily challenge of riding his bicycle to work through American and Canadian cities.

The sun dropped behind a broken finger of stone, and we pedalled on. I crouched over the handlebars and peered into the dark, trying to avoid the patches of loose gravel, sandy ruts and large stones. My five companions were strung along the road ahead like wraiths, sensed only by moonglow on white helmets, tires crunching, and the occasional grunt or muttered curse. We had not planned on this - the Bicycle Africa itinerary didn't mention anything about pedalling through the dark savanna - but Africa laughs at plans.

David Mozer, our guide, had tried to consider everything in planning our two-week tour of Mali, from the timing of each village's market day, the most colorful time to visit, to the schedule of the riverboat that had carried us and our bicycles down the Niger. But the riverboat had been a half-day late to the dusty river town of Mopti. We could stay overnight, but that would put us another whole day behind, and after two broiling days on the riverboat we were eager to get out in the open country and do some cycling. So we headed for Songo - 60 km away, with only an hour of daylight remaining. David thought the full moon would be bright enough to ride by, and if the way proved too perilous we could simply camp beside the road. But once the harsh beauty of the savanna had shaded from twilight blue to silver and black, sleeping rough seemed less attractive - nothing lights the imagination like the dark. We kept riding.

Bicycle Africa has offered tours since 1983, exploring cultures and landscapes in many countries, from Tunisia to Zimbabwe, and from Kenya to Senegal. My first trip had been a month-long odyssey through Cameroon, which now stands as one of my richest experiences. At the time, though, it felt more like a gruelling ordeal, capped by a harrowing escape through war-torn Chad. I swore I'd never do anything like that again. But, as many travellers have discovered, Africa has a way of calling you back.

The following year, I cycled through Togo and Ghana with David, and now I was back a third time, beginning a two-week tour in Mali. Landlocked in the remote heart of West Africa, more than half the country is buried under the ever-encroaching Sahara. The rest is mainly Sahel, "the boarder," a belt of parched savanna fringing the desert. Mali is a thirsty land, and sometimes hungry when the rains fail. But the upper reaches of the Niger, the "i brown god," loop through the southern part of the country, where farmers work their fields and fishermen ply the river with nets and poles. One gets the feeling that life goes on with difficulty, but generally without despair.

This trip had begun in Bamako, the capital, where the six of us - apart from David and myself, there was a California firefighter, a psychiatrist from northern Italy and two sisters, from Seattle and San Francisco - boarded the riverboat for the two-day journey downriver. It was a perfect introduction to the pageant of West African life: angular canoes called pirogues worked along the shores, men poling at each end or stooping to gather in their nets. Some carried produce or firewood; others ferried people between the sand-castle villages - adobe cubes and rectangles surrounding the rounded mud turret of a mosque. Some villages were more temporary: beehive-shaped houses of woven straw belong to the "river people," the Bozo.

We made several stops, the big boat churning into the muddy bottom and simple dropping its gangplank over the water. People scrambled off and on, shouting and laughing, singing and hawking their wares. One pirogue came alongside, heavy with bundles, boxes, women and babies, and suddenly flipped over - a chorus of shrieks as everyone went into the river. But in the African way of helping the larger family, people on our boat reached down to rescue the bundles, boxes, women and babies, and life went on.

In the larger town of Segou, we leaned on the rail as hundreds of people crowded along the shore, some wrestling on or off the boat along a narrow plank, some just watching, others selling fruit, vegetables and everything from cheap watches to baby clothes. A few of the Tuareg people stood out in their costume of head-to-toe indigo - dressed for the desert, but with no caravans to lead. They have begun to drift into the towns, trying to survive by selling their only lasting heritage: the art of elegantly crafted jewelry, filigreed scimitars and tooled-leather boxes. For centuries, the Tuareg had driven their camel trains across the Sahara, but trucks were taking over, and these proud nomads are becoming, like the Masai in East Africa, a colorful anachronism. Progress takes prisoners.

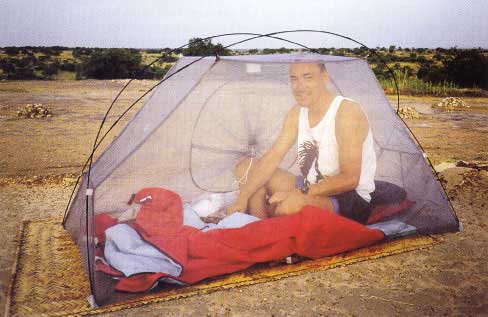

Two nights later, on the dark road to Songo, fatigue was setting in - not to mention hunger. After three hours of treacherous, anxious cycling, the moon finally illuminated a small sign at the roadside: "Campement de Songo 4 km," pointing down a faint track in the bush. With mingled hope and trepidation we pedalled into the shadows, snagged by thorns, jolted by rocks and skidding in the sand. The campement was a thatched shelter on the edge of the lightless village, where we leaned our bikes with sighs of deep relief. David performed the inevitable African ritual of bargaining for our food and lodging, and villagers materialized with shy smiles and big basins of rice and sauce, a West African specialty. Two shotgun blasts echoed around us - to celebrate a local wedding, we were told - as we set up our mosquito tents under the stars.

Songo was our introduction to Dogon country. Like the Tuareg, the Dogon are a colorful anachronism; isolation and the strength of their culture have allowed them to endure for centuries without much change. But the Dogon are settled and concentrated, their villages and farms spread along the Bandiagara Escarpment - some built right into the cliffs, like the Anaszi cliff-dwelings of the American Southwest. Dogon carving is celebrated in the West as among the finest in Africa: like the art of our Renaissance, each detail of a granary door, a mask or post in the men's meeting house reflects layers of allegory and a complex set rituals and symbols. It was easy to see why the French anthropologist Marcel Griaule spent 35 years studying the Dogon before publishing his definitive Conversations with Ogotemmeli. As we pedalled away, our only regret was that we couldn't hope to comprehend it all, and we agreed that the only solution would be another visit - Africa always calls you back.

But it calls collect and makes you pay. Our next two days offered long hours of bad riding through sand, rocks, thorns and heat, and life seemed reduced to a struggle to turn the pedals and find water. But in the way Africa has of rewarding your sufferings, we finally arrived at a medieval city sculpted of mud.

Djenne rose to prominence in the 13th century when the Empire of Mali brought wealth and refinement to the southern Sahara, and has been little altered since. Riding beneath a huge archway of adobe, we wound through the mud-walled streets to the Grande Mosquee, a massive structure of timber-reinforced mud built in 1905, replacing a similar mosque that had stood for nine centuries until it was leveled in a religious war. The minarets were capped with ostrich eggs, the exposed beams used as scaffolding to resurface the mud - each year, after the rains.

Sore from cycling, we hired a pirogue to carry us to the next town upriver. (David would want the record to show that the rest of us talked him into this.) "Environ six heures" - about six hours - we were assured, without mentioning that if, say, the motor died in our leaky old canoe, we would be stranded overnight on a desolate stretch of river with nothing to eat but rice gruel made from river water. These things weren't planned, but of course they happened. You never saw six people so happy, 23 hours later, to climb on their bicycles and ride.

Mali has no beach resorts or famous game parks, and so attracts few tourists. This is partly why visitors can travel back in time to medieval towns more true-to-life than anything in the "olde Worlde," and to pueblo villages more vibrant than any in the American Southwest - because people still live in them, much as they always have. Isolated, they are free to not change.

Traditional African life is a cycle endlessly repeated, wheels within wheels. Dry seasons and rains are the larger rhythms in the closed circle of family, tradition, music, labor and laughter. In contrast to our Western compulsion to "change the changes" - sometimes for improvement, sometimes merely for novelty - in traditional Africa what was once truth and beauty is always truth and beauty. Homes, clothing, art, proverbs, dances, religion - even hairstyles; always there is style, a sense of esthetics and protocol in every aspect of life, but there are no "fashions." In the cultural upheaval taking place in African cities, this has begun to shift - the young seem to like our revelations-per-minute approach to life - but in the villages of Mali, the old ways remain surprisingly constant.

In a Dogon village of stone, mud and thatch, just at sunset, I stood looking over the houses from an adobe rooftop, where I was setting up my mosquito tent. The only sound I could hear was conversation - no radio, no TV, no traffic, just the murmur of people talking, from that house there, that one over there, another behind. As darkness fell, broken only by stars, a few kerosene lanterns and the rising moon, I climbed down to the courtyard and joined the rest of our group, sitting and talking with some of the villagers. These are the times that call you back to Africa.

Bicycle Africa organizes six to eight tours a year to various African destinations. Each tour takes two weeks and costs about $1400 per person, including lodging, most meals and guide fees but not airfare (bicycles are carried free on most international flights). Participants should be moderately fit and capable of cycling an average of 60 km a day on good roads.

Bicycle Africa

4887 Columbia Drive South

Seattle, WA 98108-1919 USA

Tel/Fax: 1-206-767-0848

Email: ibike@ibike.org (primary) or intlbike@scn.org (back-up)