Chasing Some Midnight Rays

by Neil Peart

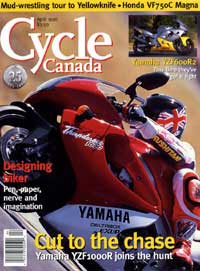

Cycle Canada, April 1996, Transcribed by Colin Wright

Neil Peart is the drummer and lyricist for the rock combo Rush, and a long-distance touring rider with a penchant for dumb ideas.

Far beyond the end of the rainbow, on his way north of 60, Neil Peart finds splendor in the mud. Or perhaps not...

It was a dumb idea to begin with, and I blame myself. Brutus and I were planning a two week motorcycle tour of Western Canada, and I mentioned that it might be fun to go farther north. Far enough, perhaps, to see the midnight sun.

We scanned the map and checked distances. There weren't many choices; in the far north, roads are few and inhabited destinations limited. A tempting little line high on the map, the Dempster Highway, reaches all of the way to Inuvik. And the Arctic Circle. But no, not this time. Same for Alaska or the Yukon - we could never make it there and back in two weeks.

Some fool suggested Yellowknife, and we started ciphering. The return journey, with a few scenic tangents, would be about 13,000 km; allowing for a day in Yellowknife, this would mean averaging more than 900 km a day, one day after another. Factor in uncertain weather, mountains, some long and remote stretches of unpaved road in British Columbia and the Northwest Territories, various police forces interfering with our idea of a proper pace and mechanical difficulties, and it looked a little daunting.

At the same moment we looked up from the map and nodded solemnly to each other. Yes, we would go north of 60 to catch some midnight rays.

Here's mud in your eye

Thus we set off on a long, hard journey, on our sport-touring BMWs - great for the paved roads, but not for the other part of the route: A Thousand Miles of Dirt. And worse: heavy rain in the Northwest Territories would turn a construction zone into a quagmire, and send us and our bikes sprawling in the mud. It was then, as I lay in the muck smeared in greasy clay and looked at my fallen motorcycle, that I knew for sure.

It was a dumb idea to begin with. And I blamed Brutus.

Going nowhere, really fast

As a general rule, we favor two-lane roads (with the odd passing lane), the choicest scenery (with a nice hotel and a good wine list nearby) and creative routing (meandering around the countryside for hundreds of kilometres, but still getting to the hotel by cocktail time). Our official motto: "Taking forever/to go nowhere/really fast."

This plan we put into effect. On the move with the rising sun, usually by 6 a.m., we made rapid progress while the roads were quiet and the world was still waking. Breakfast would come later at a small-town diner. In the first days we rounded Lake Huron and then the North Shore of Lake Superior, with its landscape of glacier-scoured rocks and windswept pines so beloved by Canadian landscape painters.

Beyond Thunder Bay, a hot prairie wind replaced the cool lake breeze, and in Manitoba the forest drew back like a curtain. The wide green prairie opened on every side and the world seemed like a disk, with 360 degrees of horizon. A quick stop at the BMW dealer in Winnipeg corrected a leaky gasket and a faulty electrical relay, and we continued west with fresh oil and filters.

In Saskatchewan, a scenic loop through the Qu'Appelle River Valley lured us off the Trans-Canada. On a sudden ridge, we stopped and looked out over the deep canyon, across to the ancient corrugated walls of the other side, and down to where a tiny tractor plowed up a long cloud of dust trailing in the still air.

Somewhere along the greasy Mackenzie Highway leading to Yellowknife, Neil Peart considers blowing his brains out. Fortunately, his finger was unloaded. Otherwise, Neil wouldn't have lived to tell us of his rainbow-blessed journey north, which included a climb on the Columbia Icefield.

In this prairie province, the Qu'Appelle Valley is, for lack of much else, a significant geological feature. The winding, grassy trails of a ski hill have even been carved into the valley wall. Yet, on the whole, the Saskatchewan landscape doesn't seem flat exactly, but more rumpled and rippled-a wide green duvet. As Brutus and I sped over the vast grid of empty roads, the fields of wheat and canola were bright from the early summer rains. My helmet filled with the perfume of lilacs as we passed the isolated farm houses. In Melville, a line of freight cars waited by the towering grain elevators-a classic prairie scene. Over a tall glass of lemonade outside the Waverley Hotel, Brutus and I discussed how our gas mileage seemed to be radically diminished by these "prairie autobahns." Some quirk of the atmosphere, no doubt.

Westward Ho

Thunderstorms whipped the streets of Regina that night and kept us awake to watch the lightning play. By dawn the prairie sky was clear, and the streets washed clean. We headed out of town on to the Trans-Canada - until Brutus ran out of gas, a hundred metres short of Chubby's gas station. it turned out his gas tank hadn't been seated properly when the relay was replaced, and now there were three full litres out of reach of the fuel pickup. This would be corrected at the BMW dealer in Calgary, where we also collected some needed supplies - more foam ear plugs, a radar detector for Brutus, a screw for my sunglasses and a good Japanese dinner with flasks of hot sake.

After breakfast at Lake Louise (still one of the most beautiful places I've been) we headed north on the Columbia lcefields Parkway. This was territory new to both of us, so we'd planned this day to allow time for scenic overlooks, hikes away from the road to view waterfalls or the turquoise waters of Lake Peyto framed among the snow-painted mountains. Time was set aside for photos and videos, wildlife viewing (black bear, white-tailed and mule deer, moose, wild bighorn sheep, ravens, magpies), and a climb up the Athabasca Glacier (breathtaking, in both senses).

The Columbia lcefields Parkway demanded time for hiking and wildlife spotting. An angry-looking bison at the side of the Liard Highway caused a moment's pause while heading toward the Northwest Territories. Before the rain and mud there was dust, torrents of dust, on the long trail north across permafrost and muskeg.

Jasper is a pleasant town catering to outdoors lovers, and from there we turned west, leaving at dawn. Mist hung on the lakes and mountains, and a herd of mule deer, heavy-antlered stags, rested in the dew-soaked grass. Through the Yellowhead Pass, we rode below Mount Robson (highest peak in the Rockies), and on into the northern British Columbia interior. The weather remained fickle, and eventually we decided that the only way to be prepared in B.C. was to wear our rainsuits all the time. With our sunglasses.

Through this remote area I had thought we could dispense with the radar detector. It was a dumb idea, and I blame myself. Sure enough, near the middle of nowhere we were stopped and charged with exceeding the posted limit. Brutus gave me a verbal thrashing, and I deserved it.

From Hazelton, a long road led away into the bush. Paved at first, it faded to gravel, then became narrow and rough until finally we reached the Sportsman's Kispiox Lodge. We checked into a nicely appointed little cabin - my favorite kind of accommodation, but a vanishing species. The swift-moving Kispiox River bustled between the trees, snow-dusted mountains rose in the distance and a sudden rainbow glowed in the south. From its end came not a pot of gold, but a Harley, roaring into my photograph and away up the little gravel road. We wondered what he was doing there; perhaps he rode by and saw our BMWs, and wondered the same about us.

The Stewart-Cassiar Highway leads straight north to the Alaska Highway, and it was partly paved, and partly not. The day was partly clear, and partly... not. We wore our sunglasses... and our rainsuits. Most of the traffic consisted of RVs, many of them traveling in wagon trains, either for safety in numbers, or because once they caught up with each other, none of them could pass (having the bulk and acceleration of a glacier).

Near the end of the longest day yet - more than 1,100 km - we were treated to the best road yet: the Alaska Highway, east from Watson Lake in the Yukon. Now traveling against the flow of RVs, all heading "north to Alaska," we had the road to ourselves. As my notes recount: "The road becomes a winding, fast delight, and the efficient. All weariness, pain, and fatigue are totally forgotten, lost in the sheer delight of riding a challenging road through majestic mountains."

After that, things turned wild. The Liard Highway, a wide, straight gravel road, leads into the Northwest Territories (where it is called, more accurately, the Liard Trail), through uninterrupted stretches of low forest, alternately dark with spruce or bright with aspens. This is the land of permafrost, without which this part of the north would be a desert-the earth, frozen year-round, holds enough water to support the muskeg swamps and scrub forest.

Torrents of dust on the road forced us to ride well separated, and at one point I came upon Brutus stopped in the middle of the gravel, pointing ahead to a large black shape at the roadside. "It's a bear," he said. "What do you think we should do?"

After a moment's consideration, I said "I'll ride by it really slowly, and you have the video camera ready when it starts chewing on my leg." When I pulled alongside, the bear sat up, faced me with its ears erect, then turned and bounced into the woods.

Another time it was a bison, a huge, angry-looking bull with flies swarming around its red eyes. Once again I rode by slowly, wondering what he would do, but the bison shook his massive head a couple of times and lumbered into the bush.

Whenever we stopped for a break or to look at a waterfall, another kind of wildlife closed in: the infamous northern insects. The big flies were called "bulldogs" by the locals, and seemed to be attracted by the heat of our motorcycles, while the clouds of mosquitoes were after our blood.

Twenty Kinds Of Mud

It is said that the Inuit have 20 words to describe different types of snow, and soon we learned that unpaved roads are like that too. Sometimes a hard-packed surface let us cruise easily at 80 or 100 km/h, while on other sections it felt as if we were surfing through the loose stones. if we looked far enough ahead, we could pick out the sweet spot - the groove left by trucks - and simply let our wheels follow it. Sometimes the bikes would oscillate beneath us, fishtailing in rhythm, and we had to learn to conquer our instinct to hit the brakes or back off the throttle - pour it on, as a dirt rider would, and you can ride on through.

A ferry carried us over the Liard River to Fort Simpson, far enough north now that at 11:00 p.m. I was reading by the light from the window of my hotel room (which had a bullet hole in it), and watching kids play in the streets outside. Next morning we were on the Mackenzie Highway, headed for Yellowknife, and that's when the rain started.

After almost 300 km of wet gravel and bleak wilderness, during which we encountered a handful of other vehicles, a ferry carried us over the Mackenzie River (the ferries are replaced in winter by "ice bridges"; the trucks just drive across the frozen river, which has the safe load ratings posted on the shore). The rain continued, harder now.

Over lunch at the Snowshoe Inn in Fort Providence, passing truck drivers told us this was the first big rain since the snow had melted, back in April, and if we were headed for Yellowknife... they shook their heads.

It seems no matter where you go in Canada, it's a two-season country: winter and construction. The road's rutted clay surface was awash, and had the consistency of paint. With our wide, relatively slick tires, it was like skidding around on a greased griddle, and we gushed slowly through deep, slippery trenches. Brutus's back wheel caught a protruding boulder, and he went down, sliding to a stop with the bike on its side. Slipping and dancing, I managed to park my bike on its centerstand and skate over to help him. Once his bike was righted, with the loss of a mirror, I couldn't get moving again - each of my wheels was caught in a different rut, and the back wheel spun uselessly, pushing me sideways down the road.

Brutus came over to help, but it was all we could do just to stand up. Soon my bike was down in the muck, and I followed, flailing into the mud-wrestling pit. A tractor-trailer driver had been hanging back, waiting for us to pull ourselves together, and as it came skidding up to us, I flagged him down and called up to ask him how long this lasted. If it went on much longer, we might be facing defeat.

"Maybe five clicks more," he told me, before trying to drive off, but he couldn't get the big rig moving again. As Brutus and I half-rode, half-waddled in the other direction, the truck's drive wheels spun in the mud, and the truck went nowhere. After stopping for me. I blamed myself, and I'm sure the truck driver did too. No doubt he's still hoping to meet me sometime, on a dark highway.

Midnight Tan

After a 10-hour struggle through the gravel and mud of the Mackenzie Highway, our first stop in Yellowknife was the spray wash, where we stood in our rainsuits and sprayed each other before we turned to the bikes. The Explorer Hotel is a surprisingly luxurious high-rise on the edge of town, and its restaurant made an excellent reward for our sufferings: Arctic char, caribou and buffalo steak, fine wine, and a decadent finish of Cherries Jubilee and cognac.

The next day we explored the city, hoping the bright sun and fresh breeze would dry out the Mackenzie Highway before we faced it again on our way back. Yellowknife's population is only about 12,000, but it's the centre of government and business for a huge territory (a million square miles, or one-fifth of Canada's area). Along its tidy paved streets, modern buildings house branches of most of Canada's franchise stores.

In contrast, the Old Town reflects the community's beginnings, with lanes that wind around a bay of Great Slave Lake. Float planes still take off and land all day, serving hunters, remote settlements, mines, oil rigs and defense installations. The rustic Wildcat Cafe and the Bush Pilot's Brew Club overlook the shore, and the daring exploits of the early bush pilots are also documented in the city's museum, which we visited before our appointment at the local Honda dealer.

It was time for another oil change, which we could have done ourselves in the hotel parking lot, but in these enlightened times, what do you do with the used oil? Also, playing in all that mud had gummed up something in my engine - it backfired loudly all over town while rough-looking characters ran for cover - and I hoped a mechanic might be able to help. The dealer was mainly geared to ATVs and snowmobiles, but the capable young mechanic, Mark, was able to find a sticking cable and get my fuel-injection back in synch.

After running on five or six hours sleep a night for a week, we were in bed early that evening, with our alarms set for midnight - the summer solstice. When I called Brutus's room, his sleepy voice told me he'd already decided "fuggit" and turned off his alarm, but now he growled: "Okay, let's get it over with." Nice talk, with our goal finally at hand. I tried to convince the night manager to let us on the hotel roof, but he claimed to have no key, so we went to the parking lot. At the stroke of midnight, a hint of sun still gleamed on the horizon, and an unearthly twilight reflected on the nearby lakes. We took it all in, got our souvenir photos and videos, and went happily back to bed.

Ahead of us now was the long homeward journey, down through Alberta to the Peace River and Edmonton, where we would pick up new tires and brake pads, then east on the Yellowhead Highway through Saskatoon and more of Saskatchewan's wide green duvet. Near Winnipeg, we would pick up the Trans-Canada again, but the sunshine would end at the Ontario border, and wind and rain would chase us the rest of the way home.

After yet another thousand-kilometre day, with cold and rain and strong winds gusting off Lake Superior, we huddled in the Parkway Motel in Wawa, Ontario. We were deeply fatigued, chilled and wind-battered. Wet clothing was spread everywhere to dry. The Weather Channel talked about more cold, more wind, more rain. A taxi delivered take-out pizza to our motel room.

At the same moment we looked up and nodded solemnly to each other. It had been a dumb idea to begin with. I blamed myself.

Brutus did too.

Webmaster note: it was during this motorcycle trip when Neil Peart was inspired by an Inukashuk overlooking the town of Yellowknife, and purchased a postcard which was later reproduced as the Test For Echo album cover.

"I was up in Yellowknife last June on a motorcycle trip across the country, and there's one of those Inukashuk above the town overlooking it, and I was quite taken with it. I bought a postcard almost exactly the image you see on the cover ... I just came back with this postcard and I thought of 'test for echo.' I thought that's exactly what these men mean when you're out in the wilderness ... when you've been hiking for a few days and you come across one of these things, it's such an affirmation that there's life out there. Again the same thing: it's an echo ... and that's the feeling a traveler in the Arctic would get, that it was a sign of life..." - Neil Peart, "Jam! Showbiz", Oct. 16, 1996