Canadian Conquistadors

Scooter Trash Rockin' The Aztecs

by Neil Peart

Motorcycle Tour & Travel, July 1996, transcribed by pwrwindows

Mexico was the author's second motorcycle adventure ever, filled with bug eating, crashing and flaming saddlebags. Not bad!

Neil Peart chooses to sport-tour on BMW's R1100RSL, having the bike flown in from his home In Canada.

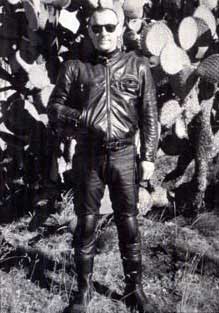

The show must go on: Brutus stretches his sore, broken bones early one morning before another long day of riding.

Peart stands in front of the Pyramid of the Sun in Teotihuacan

before climbing its 248 steps with the battered Brutus.

A quick downshift to second, a touch of the brake for balance, and bend the bike low into another switchback. On the inside of the turn, a cliff of tall pines and rocky battlements tower into the clear blue sky. On the outside, another cliff dives into space, howling down into the shadows and mist of the canyon.

Highway 90 between Mazatlan and Durango is said to be the most beautiful road in Mexico, but it may also be the most perilous for the motorcyclist. Sometimes a token sign reads curvas peligrosas (dangerous curves), or shows an arrow atop a squiggly line, but the most reliable indicators of danger are always the roadside shrines-a simple wooden cross with painted name or dale, a little stone arch sheltering candles and flowers, or even an elaborate chapel with crucifixes and electric lights. These shrines commemorate particular victims of a particular curvas peligrosas, and are often the best warning signs of all.

Our two-man bike gang was on the road in Mexico: "Scooter Trash-Rockin' The Aztecs."

When my riding companion Brutus suggested a winter tour around central Mexico, we immediately began to ingratiate ourselves with our wives and went to work on the infinite details of planning a self-guided trip around an unknown country.

The plan was to fly our motorcycles into Mexico City and have them delivered to Grupo Bavaria, the BMW dealer who would uncrate and prepare them for us. When we arrived, they'd be ready to ride. That was the theory, but it would not be so easy.

It was a three-day wait until one of the bureaucrats mustered the courage to say, "Si." On the bright side. Brutus and I had allowed for two days to clear the bikes anyway-so we were only one day late leaving Mexico City.

This gave us time to look around the world's largest city.

Two representatives from the local BMW club took us to the restaurant "Azteca," where we sampled a local specially called pollo mole, chicken bathed in a dark brown sauce made of several million spices and one of the Aztecs' enduring contributions to modern civilization: chocolate.

The menu at our hotel offered a "Selection of Mexican Delicacies," which we tried, too. When the waitress arrived with a big plate full of bugs and worms, we played it cool, but inside we were a couple of ten-year-old boys looking at a plate of bugs and worms and thinking. "Whoa!"

The verdict on eating bugs and worms? Brutus preferred the bugs. I liked the worms. But the bugs were good, too. Both of us found the river shrimp a little bland by comparison.

For the motorcyclist, Mexico is uniquely rewarding. All the mountain roads you could ever want, and a few four-lane toll roads where you can ride the speed you choose. When we asked Martin, the BMW club ambassador, what sort of speeds we should ride, he gave us the best advice: "Ride the road, not the numbers."

Our indoctrination was harsh: a night ride out of Mexico City over the mountains to Cuernavaca on a busy toll-road. Up high it was cool enough for full leathers and electric vests, but as we descended into Cuernavaca we soon heated up-and got seriously lost. Perdido. Street signs in Mexico proved to be well-disguised or non-existent, and as the days went by we were soon joking that there wasn't a village in Mexico where we couldn't get lost.

In Oaxaca we got perdido again, and spent the usual hour or so finding the hotel. In the evening we walked through the cobbled streets, closed to traffic, and admired the cathedral, the well-kept colonial buildings and the tree-filled main plaza. From the balcony of a restaurant overlooking the square, we relaxed with margaritas and enjoyed the music of the mariachis.

Oaxaca charmed us so much that we lingered there through the morning, and in the afternoon we set out for the coast-across the Sierra Madre.

The switchbacks continued for almost five hours, leading us up and around and down and around in endless, slow curvas peligrosas. A month of thrice-weekly weight and endurance routines had been good training for this ordeal, but we were still sore and tired by the time we reached the coast-just as the red sun sank into the blue curve of the Pacific.

Puerto Escondido means "hidden port," and it sure was for us. We flailed around in the dark searching for the "hidden hotel," then we became separated. Brutus was making a slow turn on an unlit back street when he hit a patch of sand and went down, his bike sliding away from him in slow motion. Despite the 9O-degree heat, we had stuck with our armored leather jackets, boots and gloves, so he was uninjured, but his luggage cases were a little rattled and so was his confidence.

A 12-hour day on the hot and humid coast highway brought us to Acapulco-to which we gave mixed reviews-and the following morning we left before dawn, beginning a long run north to Manzanillo. In the early afternoon I noticed that the cyclops-eye of Brutus' headlight was missing from my mirror and stopped to wait-already worried. With a rising pulse and a sinking heart, I turned back and saw a pickup truck pulled off the road. Three Mexican guys stood behind it, and then I saw Brutus-to my immeasurable relief-standing.

His bike, however, was laying halfway down a ravine, scratched and dirty, with luggage cases, mirrors, tank bag, and bits of fairing scattered about the landscape. Looking at this, I could only breathe a slow curse and shake my head. Then I asked Brutus, if he was really okay.

"Well, if I'm not okay, my body's not telling mc about it yet." Later, it would.

Finding himself in a decreasing-radius turn carrying too much speed and still a little tentative from the spill two days before, he'd gone for the brakes. When the bike hit the roadside gravel, it dropped him on the road, caught and flipped over, bounced upside down, crushing the windshield frame, then flipped over again to land on its side. Amazingly, the K-bike was still idling away, and Brutus struggled to his feet as quickly as he could, hitting the kill-switch and scrambling around to gather up the pieces.

Adrenalin still masking his injuries, he joined in the lifting and pushing as the three Mexican guys helped us haul the bike back up to the road. Brutus' helmet was gouged and his jacket was scored over the body armor at the shoulder and elbow, but he had no visible injuries. The bike was a mess but seemed to be operable, and a careful inspection showed no mechanical damage. Lashing tile broken bits to both our bikes, we set off again-slowly, to be sure. We were both pretty shaken up, and before long Brutus began to feel the pain and suspected what a doctor would later confirm: a couple of cracked ribs.

I don't know how he did, but he kept riding, stopping only to ask me for some Bufferins-four of them-and swallowing them down without getting off the bike. He knew that if he got off, he might not get on again. And no matter how slowly he crossed the endless speed bumps, called topes, each one was a stab in the side, and the dips and potholes were like kicks to the body.

We spent three days in Manzanillo at the Moorish-fantasy beach resort of La Hadas (the setting for the movie "10"), which made a fine sanitarium. An amiable young doctor taped up Brutus' ribs and gave him some painkillers while a mechanic flew in from Mexico City to minister the bike. Brutus was hurting-just sitting up in bed required a series or carefully planned little movements-but he could smile about it now, and he wanted to get moving. My hero.

We visited the old Spanish silver-mining cities of Durango, Zacatecas and Guanajuato, with their well-preserved colonial centers and incredibly ornate cathedrals-paid for with the lives of Indian slaves who had labored and died in the mines. Guanajuanto also offered the Museo de Momias-the Mummy Museum-which Brutus made me go and see. The minerals in the soil and the dry climate had combined to preserve the skin, hair, and even clothing of entombed bodies, and when they were exhumed-for non-payment of burial fees-the "best" ones were put on display in this macabre museum. After viewing the dehydrated corpses of over a hundred men, women, children, and babies, we were?not very hungry.

Later that day, Brutus set himself on fire. A bad bump knocked one of his banged-up luggage cases loose, which came to rest on top of his exhaust pipe as we blazed down a fast toll-road (and when I say blazed...). Riding behind him, I saw the steam of smock, but blamed it on a bad batch of Mexican gas, which had plagued us before. Then I rode up beside him and was shocked to see the plastic case wrapped in smoke and half burned away. Just then it burst into a ball of yellow flame as I watched in horror, thinking of our two-liter container of gas sitting on Brutus' rack-right above the flames. In the space of a few seconds, my overactive imagination saw Brutus enveloped in the fire. The gas can exploding and his charred corpse at the side of the road. Leaning on the horn, I waved frantically, but he still had no idea what was happening. Even when we were stopped and I ran over screaming, "Get off! Get off!" he was perplexed, "Why should I get off?" Then he looked down, and he got off.

We were able to pull the burning case away from the bike, stamping out the smoldering remains of his luggage and kicking the flaming scraps of his jeans into a puddle. This time Brutus was okay, but I was a wreck, and that night we were deep into the second margarita before I began to calm down.

Of course, most of our memories were less dramatic than my partner's "crash and burn" stunts (he told me he did them on purpose for the sake of "the story." Thanks, partner.).

In the mountain forest near Angangueo, the branches of the silver firs sagged with the weight of tens of millions of orange-and-black Monarch butterflies. Huddled together against the chilly nights in their 10,000-foot sanctuary, the morning sun brought them swarming into the air like windborne leaves, and we had to walk carefully to avoid the ones stretching their wings on the path.

Hundreds of them fluttered around our heads, a thousand covered a puddle of water like wallpaper, a few million flowed out over the open meadow below in fluttering waves. Scientists estimate that 35 million Monarchs arrive here every winter from Canada and the eastern U.S., and it is impossible to overstate how many butterflies make 35 million, though Brutus thought he'd only counted 34 million.

On another sun-washed morning we stood atop the pyramid of the Sun, the third largest pyramid in the world, in Teotihuacan. This pre-Aztec ruin is thought to have been the largest and most splendid city in the ancient world. The four-kilometer main boulevard is lined with the stone foundations of temples and palaces ending before the Pyramid of The Moon, which I had to climb without Brutus-the 248 narrow, stone steps up the Pyramid of the Sun had been painful enough on his battered ribs.

But we made it. At last we climbed off the bikes in the Grupo Bavaria garage and posed for the end-of-tour photograph, arms around each other, laughing inside our helmets.

When I travel to a place I haven't visited before, I find that I have three possible responses: one, it's a wonderful place and I can't wail to return: two, it's an interesting place but I don't care to see see it twice; or three, it's a horrible place and I wish I'd never gone there. So the essential question to ask is, "Would you go back'!" And would I return to Mexico? In a butterfly's wingbeat.

Next time. Though, Brutus says I have to do my own stunts.

Neil Peart is the drummer/lyricist for the rock band Rush, who are currently working on a new album.