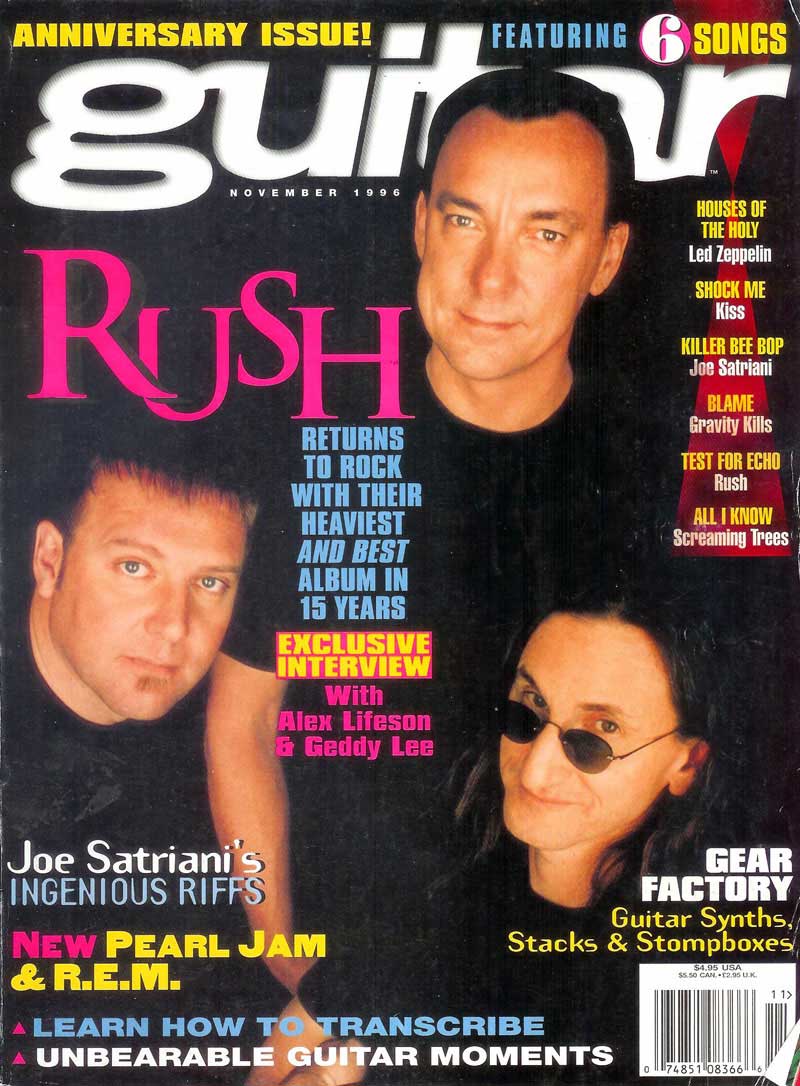

Rush Hour

Lifeson & Lee Test Their Metal With A HEAVY ECHO

By Mike Mettler, Guitar, November 1996, transcribed by pwrwindows

When we last left Rush's Alex Lifeson ("Alex Lifeson: In the Limelight," February 1996), he was coming off of a career high point. He'd successfully completed his first-ever solo project, dubbed Victor, which he had cut start-to-finish in his own home studio, and he'd just begun sessions for the next Rush album, the provocatively titled Test For Echo. Clearly, the 42-year-old axe slinger was jazzed about his prospects, for as of late November 1995, the band had already written seven new songs in record time.

A good nine months later, while talking about Echo from his home base just outside of Toronto, Lifeson reveals that getting back into the Rush groove was more difficult than he ever could have imagined.

"The first week was a little rough for me." he admits. "I just wasn't comfortable. I was really wondering what I wanted out of the band at that point. And Ged [bassist Geddy Lee] and I spent a lot of time talking about directions in our lives, more than the band and the work at hand. We decided at the end of the first week we'd see how the first couple of weeks went and then make a decision from there as to whether to continue with it."

The key question for Lifeson boiled down to this: Would Rush continue to evolve, or just spin its wheels? "It's always been very important for us to evolve," he says, "and that's why it was so critical when we started this record to feel that we were totally into it - and nothing could have convinced me to do it if I wasn't feeling right about it." Lifeson emphasizes that this was a turning point for Rush. "That was worrying for me because I was suddenly confronted with the idea of not wanting to do it anymore, and I'd always wanted to do it. But I wasn't sure that I wanted to do it in the same format anymore, and I was prepared to say, 'I'm sorry that's it for me.' We've always said that if we lose that spark, then that is the end."

The 43-year-old Lee was also concerned about the bands evolution, but as he points out during an interview session at New York's posh Four Seasons Hotel, evolution is Rush's middle name, "I just don't think we're capable of standing still," he says flatly "Even if we wanted to, something or another would force us to make things a little different, Mind you, I'm sure in the opinion of some of our critics, we do sound very similar from record to record, so maybe you have to be really close to the music to appreciate the changes in it."

Once the writing sessions got rolling, the old spark was indeed still there, and everyone was back in synch, Rush was up and running again-this time, with a vengeance. What the boys came up with for their 16th studio album, Test For Echo, is their most aggressive statement since 1981's Moving Pictures. Right off the bat, the title track digs in courtesy of Lifeson and his newly acquired Les Paul Custom, leading directly into the propulsive "Driven," which is fueled by three tracks' worth of Lee's gutty Fender Jazz bass lines. By the time you get to the hard-hitting intro in "Dog Years" ("It is a bit punky" laughs Lee), you realize that Rush has struck gold.

"Moving Pictures was the same way," Lifeson notes. "We were feeling really good when we made that record, and we were really clear in what we wanted to do. That record shows the positive energy going on at the time it was made, and so does Test for Echo."

The main reason that this album is a comparably exciting, vibrant work is time, and lots of it. After the Counterparts tour wound down in the spring of 1994, the members of Rush did what they had never really done throughout the course of their 22-year career: They took an extended vacation away from each other. Lee and his wife "got domestic" and had a baby; Lifeson did the Victor project; and drummer Neil Peart produced a tribute record to Buddy Rich and studied with Freddie Gruber, the "guru of swing drumming," according to Lee.

"If we hadn't had that time off, I doubt we would've made a record like this," Lifeson says. Lee concurs; "I'd say the break was overdue. We've always been such workaholics. It was a good time for everybody to stretch out a little bit and get their lives in some sort of order." With their heads clear, and Lifeson's concern about the band's future swept aside, the duo penned the Echo music at a feverish clip at Chalet Studio, just outside of Toronto. "We didn't realize how refreshed and ready to go we were," Lee recollects. "A lot of ideas were coming very quickly. We decided to do most of our writing on stringed instruments as opposed to keyboards. As soon as you start writing on a keyboard, a song takes a totally different direction. Actually, I felt it was almost a shame to have to stop writing; in fact, part of me wanted to do a double record. I felt we could have easily written 10 more songs, but I don't know if Neil had lyrics for 10 more songs. I certainly felt we could keep going, but we stopped at 11, a nice round number," he chuckles.

Lifeson had to slow his frenetic pace once he started tracking guitar parts, since he still needed to get in tune with a new dimension that had been added to Peart's drumming. While Peart has always been cited as one of rock's most mechanically sound drummers, he made a concerted effort to improve upon his feel (hence the intense sessions with the aforementioned Gruber). "He's taken his playing to a whole different level," Lifeson marvels, "but I think we all did for this record. It just took me a little while to feel the way he was feeling. Generally, I was racing a little bit the first day or two we were doing guitars. I had to lock into where he was feeling the beat; it's not like it was on the backside of the beat or anything like that. He was slicing it really close, though. I was also more aware of what he was doing on the ride cymbals, so I tried to fit the acoustics in with that quality of the rhythm section."

Lee also admires Peart's progression. "He's been reinventing his style, to a large degree, to accommodate an improvement in his ability to swing and feel things a different way" Geddy says. "And that approach has impacted on the tonality and setup of his drums, the end result being that he sounds a little different and plays a little different. That also affects how I work with him. It doesn't affect the main thrust of the songs, but occasionally it'll affect the dynamics of a song, which might necessitate a change in the feel of a part."

The first track where everything clicked was "Driven," an important indication of where the record was heading. "Driven" is in fact a good representation of Echo as a whole: propulsive, never complacent, and always on the go. "It's a pretty heavy song; I mean, we wanted it to give that sense of being driven," Lifeson claims. "Neil was a little bit back on the beat, which gave a heavier character to the song. I tended to race a bit on that one, too, until I clicked in on where I needed to be. Ged had to make the same adjustment that I did, but it really makes a difference."

Adds Lee, "That whole song was written on bass. There's three separate bass tracks on there: the main part, the harmony bass, and sub-bass for the bottom end - and they actually let me get away with it!"

"Driven" was the first track to reach the mixdown stage (done at McClear-Pathe in Toronto), too, and also marked the first time the band had worked with mixing power-house Andy Wallace (Nirvana, Rage Against The Machine, Faith No More). "This is the first time we'd worked with American engineers," points out Lee. "We'd always worked with British or Australian ones - a lot of Commonwealth engineers, I know [laughs], but that was an intentional decision. We wanted to work with somebody who had a slightly different approach sonically because we wanted the record to sound a little more dry and a little more up front, and I think it was a good mix. I didn't know what to expect, but I was pleased to work with both [engineer] Cliff Norrell and Andy Wallace."

As usual, Lifeson went into his new project armed with an arsenal of gear, "I took all of my usual suspects into the studio - the 30-35 guitars that usually came with me," laughs Lifeson. "But I picked up a new Les Paul Custom that really sounds great; it's a real heavy piece of wood, it's really dense, and it sustains for weeks, so I used that quite a bit. In fact, I would say 70 percent of the record is the Les Paul. Also, the fine people at the Fender Custom Shop put together a '63 reissue for me with the original coilings and pickups. And then, of course, there's my trusty Telecaster and my Paul Reed Smiths."

One thing that certainly spilled over from the Victor project is the presence of Alex's guitar tracks. On Test For Echo, they're way up front, something both Lifeson and guitar fans have been pining for over the past few years. "Yeah!" Lifeson exclaims. "Wish came true! To me, it just sounds like the guitars are in the right place - very present and quite bold, but not overpowering anything. You can still hear everything clearly. It just adds to the overall impression of power."

There's also a nice mix of acoustics on tracks like "Totem," "Resist," and "Half The World," which features the 10-string mandola Alex first utilized on Victor. "I really like the effect of having the acoustics backing up the electric parts; it makes for a denser, thicker impression," Lifeson explains. "I got to use my Gibson Dove J-55, a small-bodied Larrivée, and a beautiful-sounding Martin that was so easy to record."

Amp-wise, Lifeson stuck to his typical Marshall setup: 50- and 100-watt JCM 800s and two Anniversary 300 Series models after dabbling with Hiwatts and Peaveys. He also used the DigiTech 2101 preamp and Palmer speaker simulators that worked so well for Victor. Geddy stuck with his trusty '72 Fender Jazz bass, which had played such an important role on Moving Pictures (while many people assume Ged played his Rickenbacker 4001 on "Tom Sawyer," it was actually the Jazz). Lee had returned to the Jazz during the Counterparts sessions after being a Wal banger for a number of years.

"While the Wal has a bit more finesse in its sound - it has a snappier top end - it's not quite as aggressive in the midrange. It also doesn't have the same bottom-end response that the Fender has," Lee explains. "The Fender has a warmer, slightly more crude bottom end, and that's what I was after. I just wanted to have a lot of subsonics going." Geddy wound up recording direct, using a combination of a Demeter tube direct, a Palmer speaker simulator, and a SansAmp. When the band commences its tour in October, Lee will utilize the Trace Elliot Quatra 4VR amps and the Trace Elliot GPI2SMX preamp he had in place for the Counterparts tour, and he also plans to experiment with the SansAmp and the Palmers.

Being that Echo is the bands fourth studio album since the release of its last live album, l989's A Show Of Hands, tradition dictates that late 1997 will see the release of the hand's fourth live album, the content of which will be decided when the band takes a break from the first leg of its tour in January. This, of course, begs the question: With such a wealth of material, are there any plans for a full-blown Rush box set somewhere down the line? "Probably," says Lee. Any bonus tracks? "Only if we write something new for it." Does this mean there are no unreleased tracks lying around in the Rush archives? "No," he states firmly "I don't really believe in that. To me, if a song's not good enough to be on the record, then throw it away. Why have substandard stuff lying around? I think it just waters down your standards. If it wasn't good enough to make your record, clearly in your view, it's an inferior song. If it's inferior in your eyes, why give it to the public?"

Then there's the matter of Rush's critics, of which there are many. But the boys in the band - who Lifeson has dubbed "the indestructible brotherhood" - aren't fazed in the least that they've never once made the cover of Rolling Stone, even though they're one of the bestselling bands of all time. "Hey anybody who says a bad thing about this record better watch out," Lifeson jokes. "Seriously, you know what? I don't know if I'd ever want to be on the cover of Rolling Stone, to tell the truth. They have this thing against us. I have a sense that they go out of their way to ignore us, so at least they're making some kind of effort [laughs]. We've been around tor 22 years with the same lineup; we haven't broken up and then regrouped. A lot of bands have cited us as influences, and that's great. That's what really means something to me - that I've passed something on. I've been a teacher in some way and that's really much more gratifying. So I couldn't give a shit if we're ever on the cover of Rolling Stone. Just the fact that we haven't been is really cool, so I hope that doesn't get wrecked now."

Lee has his own view of the critics. "Listen. Everybody's entitled to their own opinion, and there's no way were going to make all critics happy, but it really doesn't matter. It's nice that our records are liked, but it's impossible to have them liked by everybody because the nature of what we do is a little strange. We have some abrasive qualities in our music, and that's just the way it is." Lee leans forward on the couch, smiles, and adds with a wink, "I'm sure there are Rush fans in the White House. Maybe one day all those closet Rush fans lurking in the shadows will come out of the woodwork."

And even though they are hardly the darlings of critics or MTV have they ever considered the ever-popular Unplugged route? "Oh, sure," says Lifeson, tongue firmly in cheek. "That'll happen somewhere around 2015."