Rush - Moving Pictures

A Conversation With Geddy

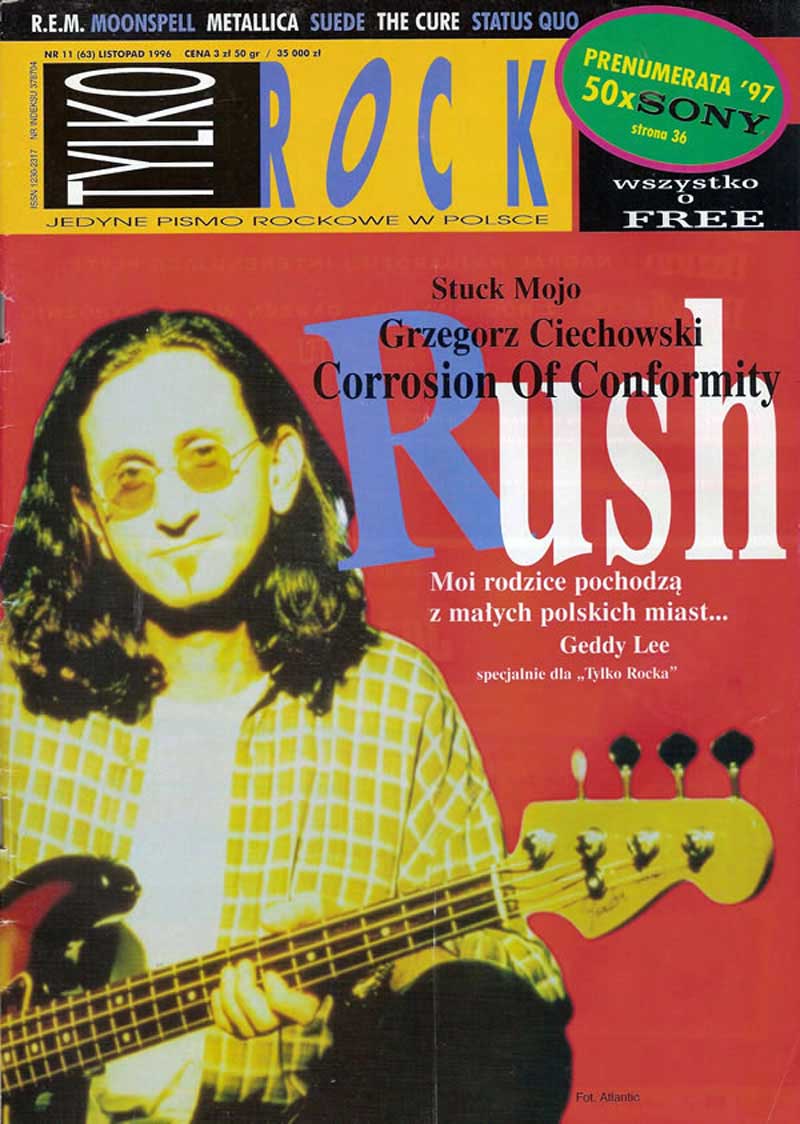

By Wieslaw Weiss, Poland's Tylko Rock, November 1996, translated by Phillip Goss

Rush was formed in 1968 in Willowdale, a suburb of Toronto - nearly thirty years ago. Or maybe we should say, over twenty years ago. Anyway, that's how Geddy Lee, the vocalist, bassist and leader of the group, says it - as if to make the group appear younger. It's as if he come to terms with the thought that they are a dinosaur in the world of rock. He doesn't have anything to be ashamed of. Rush's nearly thirty-year history is, for their many faithful fans, one of the most fascinating parts of rock history. At least a few records from among the rich works produced by the trio are already considered classics. 2112, if nothing else. Or Moving Pictures. Or... Can we also add to this list the just-released album Test For Echo? Maybe. In order to answer this question, we'll need to wait a little.

Eighteen Months

It's been three years since the release of your last album, Counterparts. Why did we have to wait so long for Test For Echo?

The last Rush concert tour ended in May of 1994. My daughter was born a week later. I decided to take a brake in order to be with her. I left the musical life for eighteen months. It wasn't until after this period that we started working on Test For Echo.

A journalist from Billboard wrote this: "It took some time before they were able to make it work, but after an initial period of reciprocal approaches, they found their muse." How do you remember this?

From the beginning, after such a long break, we got together. It really was a little strange. I was still immersed in home and family life. Alex, however, had just finished work on his own album "Victor," so he was warmed up and burning to get to work. And because he has finished a session during which he had to make all the decisions, it could be sensed sometimes that he felt as if he were our boss (laughter). As usual with Neil, he is there from the very outset and gives the appearance of being slightly lost. So a little time had to pass before each of us had found our place again. We were like three howling dogs closed in one room (laughter). We needed a few days before we were all on the same page of the same book which we were trying to read together. You know, during those first four or five days we really didn't make any music. We talked, goofed off, and we tried to answer for ourselves the question What is Rush after these twenty-odd years? Why are we still together? Luckily we were able to regroup and create an atmosphere favorable to making music. From that moment on, everything went smoothly. We got to work with an amazing amount of energy.

Rush's new music sounds very fresh. What do you think influenced it?

I have no idea. Maybe it's a result of those discussions we had during the first days of the recording session. Maybe it was because we had taken a break for a while. And maybe because the future of Rush had come into question at that time. You know, it's quite possible that nothing better could have happened to the group than a two-year break. I, for one, am able to get behind such a statement. I had never worked on an album with such enthusiasm as I did on this one. I was really exited to get to work. I don't know, maybe I just wanted a change, but I really wanted to get back to playing. Once we got into the studio, I was really happy. So maybe the answer to your question is that we were just happy to be working on the album (laughter).

Earlier you mentioned Alex Lifeson's solo album, "Victor." Do you think that this music, irrespective of earlier Rush works, influenced in any way Test For Echo?

I don't think there was any direct influence. In my opinion, it was important that Alex got to record his own album, and that he was able to have the main role in it. I think that for him, it was an immensely important experience which undoubtedly gave him self-confidence as its creator. What's important is that during our work on Test For Echo, he came at it as a musician full of confidence in his own abilities, and was therefore very relaxed. This fact was undoubtedly a positive influence on our album.

Do you like his record?

Hmmm... I like a few things on it.

Test For Echo

Alex said in an interview: "During our 'Roll The Bones' period we started going back to a sound supported only by three instruments - guitar, bass and percussion. Since than, we have consistently steered ourselves in this direction. On 'Test For Echo,' there are no keyboards." What were the reasons for this return?

First, we wanted to make fresher music. We regretted not being able to enjoy playing our tunes live. Because there are only three of us, playing any piece requiring the use of keyboards is rather difficult. It was a calling, and so it was neat. On the other hand, however, it was rather frustrating because you never felt comfortable on stage. So in part is was a change in our sound, and in part it was all about greater freedom on stage.

My favorite piece on Test For Echo is the title track, Test For Echo, as well as Time And Motion. Could you elaborate for us on the circumstances surrounding their conception?

As for Time And Motion, it started as lyrics, but the music came very quickly. The first phrase came from the feeling the words brought to us. Afterwards, we thought it would be worthwhile to dramatize it somewhat, so we introduced those major chords. You know, that piece could be called a reject. The first version was created a few years ago, but was never used. In the end, it emerged in a somewhat different - and in my opinion, more interesting - shape. It is also one of my favorite songs on the record. The history of Test For Echo is more intricate. First we had that maniacal riff which set the character for the rest of the piece, but that was just the base. In this case, we depended on it to create music with rich and dramatic segues, one moment full of space, full of air, the next changing into something pursued, maniacal, with a layer of rhythm which turns heads.

The Limbo instrumental is a slight departure from the character of the other songs...

Creating music is our greatest thrill (laughter). While composing it, we felt no compunction to keep with any conventions. We always reserve this pleasure for ourselves at the end of a recording session. When all the other pieces are ready, we relax by playing around with various musical ideas. It could be anything, and that's how we came up with the title Limbo, because it so accurately describes the character of the music. It was crated from many fragments which had been running through our heads for a long time, but just never worked. We took them to the shop and we began to work out how put them together into a greater work and what to do in order to connect them and fill them out. So Limbo is a crazy, strange mix. STRANGE WORLD

What meaning do the lyrics on Test For Echo have?

We are famous for lyrics which carry a lot of weight. We also write songs whose lyrics are important for the listeners. Given this situation, today we are really forced to write lyrics of a weight not less than the music itself. This is true at least for Test For Echo, which seems to be interesting because it accurately reflects the current situation in the group. I mean, despite the fact that Rush has existed for over twenty years, when we got together after the break to do the next album, we were not certain that anyone listened to our music anymore... that what we do means something to anyone. So this song is a kind of question: "Is there anyone out there?" Its lyrics also allow for a certain realization as to how strange the world had become for the group Rush. (laughter).

Peter Collins, a co-producer of a number of your earlier albums (Power Windows, Hold Your Fire and Counterparts), helped you to record Test For Echo. How do you rate his input in the success of Rush?

His role was, above all, that his works strengthen our belief in ourselves. Peter is a guy who feels the weight of responsibility for his word. He is very objective. If he tells you that you've composed a good song, you can believe him. But that's not all. Let's imagine that I put out ten songs, and he tells me that seven of them are sound good and it isn't worthwhile to spend more time on them. It's enough to record them as best we can. As for the others, he is not convinced that they are good. Then you can be sure that he will come right back with very bold suggestions as to how to correct them. He is good to work with. I think that he would handle himself well with any kind of music, because everything receives the same dose of objectivism. He is also a good producer for us because his thoughts regarding music are free of questions regarding recording logistics. He respects the recording engineers with whom he works, and turns over such matters to them completely. He concentrates on making the album good in its entirety.

Something Neat

I read somewhere that the first song you ever learned to play was "For Your Love" by the Yardbirds. Could you tell us more about your first musical fascinations?

God! I don't remember anything anymore... In the beginning I liked Roy Orbison. Later, I liked such groups as John Mayall's Bluesbreakers, Cream, The Yardbirds. Later yet, I liked British progressive music.

And under the influence of such recordings, you decided for yourself to begin playing?

Not completely. Before I began to play, I met people who already knew how. I thought that it was something neat, a great way to have fun. And besides that, I was, you know, a little high-strung. But as soon as I began to play the guitar, I calmed down. That was also an important incentive for a fourteen year old who wanted to be a cool guy (laughter). And in general, it was a pleasant feeling to discover something as a young man which I wasn't too bad at.

Who was your idol when you began playing the bass?

Without a shadow of a doubt Jack Bruce. He was a god to me. I was also amazed by Jack Cassidy of Jefferson Airplane and John Entwistle of The Who.

Do you remember your first concert with Rush in September, 1968, at an underground cafe beneath an Anglican church in Willowdale?

You know, Alex called me around 4 PM. He said that their bassist (Jeff Jones, the original bassist for Rush) had gotten drunk and they were looking for someone to fill in. We only had time for a short practice right before we had to go on stage. We could say that I really learned the material during the concert. It was a good time, but I admit that I got a little frustrated. I remember that evening very well.

You supposedly played Cream songs for the most part.

Yes, Cream, but also John Mayall and... No, I don't remember what else (laughter).

I read somewhere that in May of 1969 you got kicked out of the group. What happened then?

I don't know... Those were crazy times. A four-person group was formed in which there was no place for me (the group consisted of Alex Lifeson on guitar ad lead vocals, John Rutsey on percussion, Joe Perna on bass and vocals, and Lindy Young on keyboards and backing vocals). I founded a group called Ogilvie with more of a blues profile. I managed rather well and played quite a few concerts, but their group fell apart. Alex and John were all that was left, and it came down to them not being able to go on without me. So they asked me to come back... (laughter).

An Old Photograph

Why was it that for Rush's first single, recorded in 1973, you chose a rock'n'roll standard, Buddy Holly's Not Fade Away, and not one of your own pieces?

I don't remember, it was so long ago... I suppose that our manager figured that we should play something that people would recognize and not one of our weird songs. You know, at the time we were trying to survive by playing in bars, and in these bars, no one wanted to hear our music. They only wanted hits they recognized. Our compositions were probably too strange for them.

How do you rate today Rush's first album, "Rush."

I can't listen to it.

Why not?

It's as if I were looking at an old photograph taken twenty years ago. It's exactly the same feeling. Looking at yourself you can't get over it: "That's really me? Wow! I was so young! Look at those funny glasses! And why did I wear such stupid-looking clothes?" It's the same with music. You look at yourself and you're astonished that you'd play something so naïve. Today you'd play it much better. Maybe some people still like some of the songs, but only one is defensible much more so than the others - Finding My Way.

Your first big concert in the US in Cleveland, in June of 1974, is considered to be one of the turning point of your career. You played after the Hungarian group Locomotiv GT and before ZZ Top.

Yes, I remember that day. I had stage fright and was walked on stage with my legs shaking. It seems that John Rutsey still played with us then. Yes, that was the one and only Rush concert in the US with John Rutsey. (Geddy forgot that a few weeks earlier they had played a concert at a small festival in East Lansing, Michigan.) It was quite an experience. It was just that we were in the US and played in an American theater. It was amazing for us. You know, we were very young then and it was what gave us breath in our chests.

The Missing Element

Was John Rutsey's departure in July of 1974 a big disappointment?

It was very difficult, mixed-up time. There were lots of problems. It became evident that we could come to a solution by him going his way, and us going ours. There were a lot of mix-ups, and honestly, we were a little scared because he left just a few weeks before our first US tour. We had to really hurry to find someone to take his place. We got really lucky. One day the door to our practice room opened and a confused-looking young guy with a little drum set under his arm. And son-of-a-bitch... he played so well he knocked our socks off. His name was Neil Peart. Yes, that was a very lucky moment in Rush's history.

In your opinion, how much did the music of Rush change once it became you, Alex and Neil?

You know, Alex and I always wanted to play more complicated music from the very beginning, but John didn't have such ambitions. It wasn't until Neil came into the picture that we were able to turn those plans into reality. The arrival of Neil was like finding the missing element from the group. There was one more person with us who also wanted to play more refined music. We could say that, in his own way, he was a catalyst in the history of Rush. It was a person who really calmed our ambitions.

However, around the time of Rush's third album, "Caress of Steel," you said in an interview with Guitar World: "OK, maybe we should hang up our guitars and go home." What happened to make you lose faith in Rush?

"Caress of Steel" was a personal album. Besides, I suppose we were too idealistic then. On the other hand, if you are a musician and are as old as we were then, (e.g. twenty, twenty three - auth.) you should look at everything idealistically. That was a time of idealism in human history. Since then, we have encountered negative and disappointing attitudes every step of the way - from management, record labels, concert agencies.... We mostly played in small clubs back then, and even if we played a larger concert hall, it was only as an opening act. It was all very chilling. We didn't know how to draw any positive energy out of ourselves. We never heard any words of encouragement like, "Good work!" or "Play some more!" Nothing. So we began asking ourselves if it was worthwhile to continue. Is it worth traveling all over North America for months on end, when no one sees anything worthwhile in what we are doing? Well, we thought that maybe it was better to break up.

Was there a particular moment in the history of Rush that you had any doubt in your common future?

No. I admit that in the last few years all three of us have lived through moments of doubt in the value of what we are doing. You know, when you are together as long as we have been, you have to begin asking yourself why you are together. Are we doing this only because we have been successful? Or is it that only with these particular people are we able to create something worthwhile, that we as a group have something musically important to say. I think that the longer you are with each other, the greater you feel the need to prove to yourselves that it continues to make sense, and that it's not a waste of time. To remain a member of Rush just to be a member of Rush - it would be difficult to live with something like that. No one from our trio would want to feel that he is in Rush for any reason other than his continued belief in our music.

An Act Of Rebellion

After the unsuccessful album "Caress of Steel," you recorded "2112," which is regarded by many as a seminal rock album. What do you think it was that brought about such extraordinary music?

That album was born of great desires. That, and an enormous amount of energy. I think that it was an act of rebellion against the whole negative attitude I mentioned earlier. That was our way of saying, "Fuck off. Leave us alone. We know what we want to do and we are going to do it." I think that that kind of desire, and that kind of energy which we had then was a huge influence on us creating that kind of album and not another. In my opinion, it was the first Rush album which was our creation from beginning to end, where outside influences have been taken out. And even if you can hear other influences, our sound covers them. So, "2112" was the album on which the sound of Rush was born.

In an interview you said that on "2112" you tried to imitate in sound what Ayn Rand created in the books with words. Could you tell us more about the source of you fascination with the works of Ayn Rand?

We could probably say that in the history of Rush, that is when the "Ayn Rand era" began. What caught our eye wasn't her political point of view, but rather the artistic merit of her work. If you read "The Fountainhead" in juxtaposition to "Atlas Shrugged," you will understand what I'm talking about. She describes a longing for works which are a reflection of the artist's individual expression. This the conviction that the faults of any expression also decide its honesty. After all of the difficulties we experienced during our first era up through "Caress of Steel," reading through something like that was an extraordinary inspiration. We had begun to lose a little faith in our artistic vision. It wasn't until then that our vision began to take shape, original as it may have been. The works of Ayn Rand, especially "Anthem" and "The Fountainhead," were real eye-openers for us then. They gave us the strength not to sell out and to keep doing our own thing.

Sword And Sorcery

I may be mistaken, but I get the sense that "Moving Pictures," with cuts such as "Limelight," was a more personal album than any of the earlier Rush albums. What do you think about that?

It seems to me that "Limelight" is a piece that describes a never-ending battle like Neil himself was going through then. It became his attempt to view himself from a distance. It is a question about the sense of our activities, as well as an exegesis on the demands of fame and the discomfort which accompanies success. I think that working on the lyrics was a form of therapy for him. It helped him to ask himself a few important questions. I couldn't say to what level that personal perspective comes through in other songs from "Moving Pictures." I just know that we felt very isolated from the rest of the world while we were working on that album. You know the atmosphere of a prison in a home which is snowed-in. had a similar mood during those seemingly-endless months while doing "Test for Echo." We always become closer to one another while working in such an environment, and it puts more emotion into what we do.

"Moving Pictures" is the next classic Rush album for many people. What is your relationship to it?

I am truly proud of it. I like "Moving Pictures" a lot. The combination of both rather refined music and hard rock really satisfies me. You know, we always tried to put three different things into our music: the structure of formal progressive rock, a beautiful melody, and the expression of hard rock. Often, nothing ever came of it, but sometimes we got exactly what we intended.

Alex characterized that moment in Rush's history as follows: "We had already given in to the climate of the 1980's. We had decided to break away from the aesthetic of swords and sorcery... to freshen it all up - from an external viewpoint regarding musical creation and performance." How do you remember this? Was "Moving Pictures" really the point of no return in Rush's career?

Maybe, in a certain sense, but rather for me, such a point of no return was one album earlier, "Permanent Waves." It was there where the experiments began. "Moving Pictures" is the fruit of these experiments. Anyway, these two albums have an equal meaning to me in the history of Rush. Besides that, you know... I don't really remember a time when I said to myself, "Good, it's time to change and to break away from the aesthetic of swords and sorcery." It seems to me that the change occurred in a natural, evolutionary way.

Rock'n'roll

A journalist from "Kerrang!" wrote in his review of "Roll the Bones" that "[T]he group has uncovered the roots of rock 'n' roll again. The composition is quite hot, and I feel fire in them being played. This is the best album Rush has come out with in a long time." Do you think that this is a good assessment of "Roll the Bones?"

I don't know. It is certainly the best album from the time period beginning in the late 1980s and through the 1990s, at least insofar as composition is concerned. It is difficult for me to judge our music from another point of view. There are a couple of really nice pieces on it, like "Dreamline," "Roll the Bones," and "Bravado." In my opinion, it is one of the best compositions we have ever been able to produce.

Your following album, "Counterparts," was very warmly received in Poland....

You know, "Counterparts" was a very drastic change in the group's sound, and in my opinion, it resulted in one of the best-sounding Rush albums in a long time. In this respect, it was a giant leap forward, especially in relation to albums like "Roll the Bones" and "Presto." There is no doubt that there are a few numbers on it - I really believe in it. I would say "Nobody's Hero" is a good example.

Roots

May I ask you a personal question? I know that your parents were born in Poland but moved to Canada only after [World War II]. Could you tell us more about your relationship to Poland?

Yes, it's true that my parents come from small Polish towns. Mom was born in Starachowice, and dad [was born] somewhere nearby. As Jews during the war, they ended up in a concentration camp in Germany, but they survived and, after their liberation, emigrated to Canada. I was in Poland recently. My mother returned to her homeland last year [1995] for the first time since the war. She wanted to show us - my brother, my sister and me - the place of her birth, upbringing and youth. She wanted to take us to where our family has its roots. We spent a few days in Warsaw; later we went to Starachowice where we were able to find the house in which she had lived. In the end we went to Krakow for a few days. It was a very interesting trip.

Do you think you will ever come to Poland with Rush?

Nobody knows. (laughs) It's difficult to say what our concert plans will be for the next few months, because nothing has been set yet. Personally, I would like the group to come to Eastern Europe, because I know we have fans in this part of the world but have never played here. We aren't youngsters anymore, and not everyone in our trio is so enthusiastic about playing concerts. Presently, it is very difficult for me to come to terms with my friends about any concerts at all, let alone concerts in such far away places. I really can't say what will happen.

I read somewhere that you plan to release a live album in the near future....

Of course. We recorded a few concerts on the last tour. We also want to record a few more I think. We have some old material which we may use as well. I hope we will be able to come up with an interesting live album with a retrospective character.

To finish our conversation, is there anything you would like to say to all your fans in Poland via "Tylko Rock?"

I would like to thank them for being Rush fans and for supporting us for so many years. I hope that we'll make it here someday, if not to Poland, then to some place close enough for them to come see us live in concert.

RUSH: 2112, Mercury (1976)

By Krzysztof Celinski (translated by Phillip Goss)

2112 is a milestone in Rush's repertoire. It was not only another step towards progressive rock, but also a confirmation that the Canadian trio is not easily pigeonholed. With the formal art rock wave and stylistically varied, and sounds associated more with groups like Yes, Genesis or even Jethro Tull are combined with this "traditional" hard rock group on this album. The literary treatise of the 2112 suite, over half the album, is "cosmic mysticism." A virtuoso performance of instrumental motifs are often reminiscent of the characteristics of Yes ([e.g.] "nervous" progression in Overture, vocal melody in Discovery) Genesis ([e.g.] also to melody in Discovery) Jethro Tull (sound, articulation and progression in Presentation) and even The Who ([e.g.] chord progressions and rhythms in Soliloquy)! Using naturalistic effects like the "squawk" of an accelerating record album, "cosmic" sounds, and the blast of a rocket lifting off or the rush of a waterfall enriches he trio's proposition. If we take into account the formal wave in the suite, we are still more convinced by the five unrelated songs. The hard rock (with the most exciting riff on the album) and somewhat jokingly oriental A Passage to Bangkok is one of these, as is The Twilight Zone, with its well-defined phrases and Led Zeppelin[-esque] vocal mannerisms. This musical variety is rounded out by the delicate, slow-pouring Tears, and the more formal variation of Something for Nothing (a mix of Rush, Led Zeppelin and The Who...).

2112 is an attempt to the art rock formula with the "old" Rush style, but... Messrs. Lee, Lifeson and Rutsey [sic. Peart] weren't able to create anything truly different. Maybe it just isn't possible in such a small group? Nevertheless we must admit that if anyone is able to do it, it would only be Rush.

RUSH: Moving Pictures, Mercury (1981)

By Krzysztof Celinski (translated by Phillip Goss)

The best Rush album? Many people, including many musicians, think so, and the number of albums sold confirm it. It isn't my favorite album from this group, as it is an attempt to blend "ordinary" progressive rock with "proud" elements of art rock (influenced by Genesis) and the more innovative sounds of new wave, which lightly run into The Police. However, in relation to the softer releases of Rush, this album sounds like the continuation of earlier musical pursuits. Geddy Lee's voice is rarely heard in its characteristic, high register. It is less emotive in this middle coloration, and maybe that is why I'm not so fond of this album.

Probably due to the increased fascination with electronic keyboards, hard rock guitar groups don't need gimmicks. This music is richer than earlier genres, but also loses too much - in my opinion - as live rock. It doesn't change the fact that Rush perfectly written execution (there are playful synchopations and fast guitar-bass unisons - like in YYZ). Foreign stylistic elements to the trio have been included in their previous arrangements: jazz rock in YYZ, reggae (yes!) in Vital Signs, or typical new wave guitar sounds in Red Barchetta. One doesn't feel the least but of disharmony in these musical climates which are "foreign" to Rush. And, what may be most important, it doesn't seem to have been... forced. So Rush finally and victoriously defended itself. They shouldn't be surprised that the album is so well appreciated by rock fans.