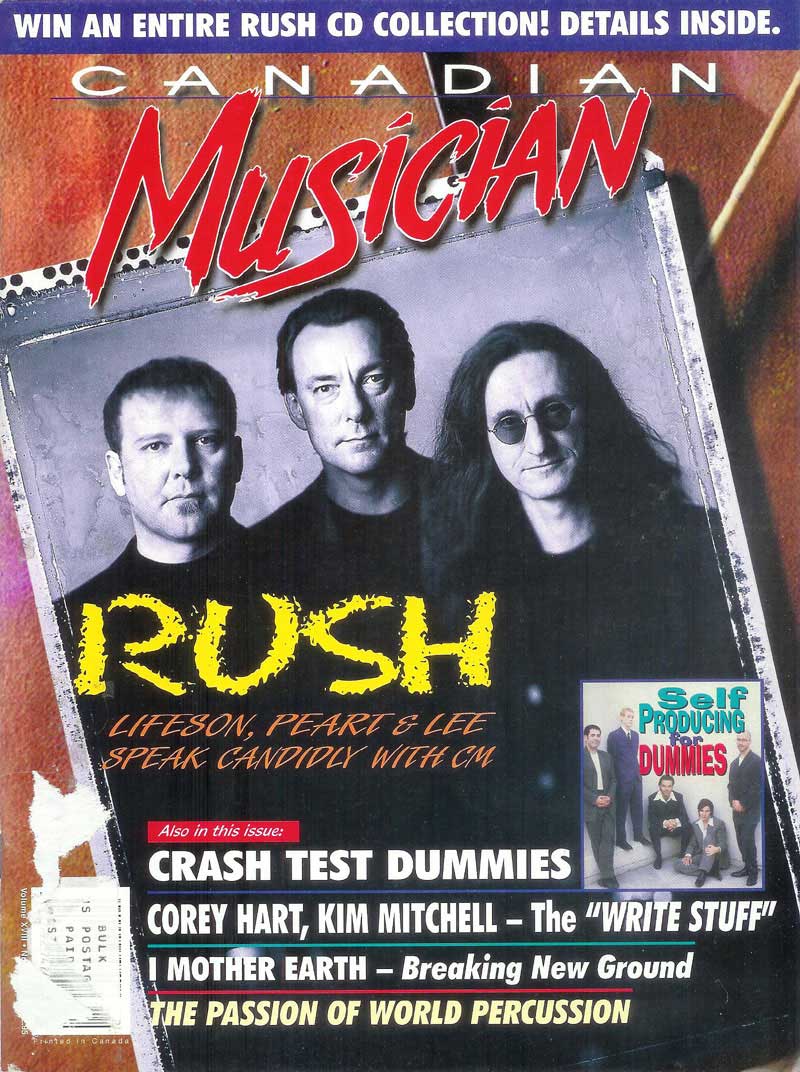

Rush Put Themselves To The "Test"

(And End Up Even Closer To The Heart)

By Paul Myers, Canadian Musician, December 1996

Before the word "independent" meant grunge and before the word "alternative" became meaningless, there was Rush. The triumvirate of Alex Lifeson's kerranging guitars, Neil Peart's propulsive drumming topped off by Geddy Lee's high wailing and nimble bass works is responsible for a sound, and a career, that is unparalleled in the Canadian or International music world. They are adored around the world by musicians and non-musicians alike, while their riffs and progressions are mulled over by music students of all ages.

And, like David Hasselhoff, Germans love them. From 1974, when the band released its eponymous indie debut, through to 1993's Counterparts, the band recorded and toured relentlessly, releasing 16 studio albums and three live albums. Then, after the Counterparts tour ended in May of 1994, Rush celebrated their 20th anniversary by giving themselves something they hadn't had in a long while, a life outside the band. They took a holiday from being Rush.

Eschewing sleeping in, the three overachievers each busied themselves during the break by making something different. Alex made a solo record called Victor, Neil made an album in tribute to drummer/hero Buddy Rich. Geddy and his wife made a baby girl. Last October, the dynamic trio reconvened at the Chalet Studio in Claremont, Ontario, where they had previously written many of their records, to begin writing their 20th album, Test For Echo. ("Everybody needs an 'echo', some affirmation lo know they're not alone," writes Peart in the official Test For Echo user's manual".)

Having spent most of their adult life together, all three were happy to walk anon" the normal people for a year or so. But more importantly, a;; returned to work refreshed and more prepared than ever to work together. Among the slogans that the band posted in the studio was the curious, and grammatically challenged, phrase "INDIVIDUALLY, WE ARE A ASS BUT TOGETHER WE ARE A GENIUS". Perhaps this. more than anything, summed Up the mutual feeling of confidence and true collaboration that prevails on this record. But first there was coffee.

"The first few days we didn't do any work," recalls Lifeson. "Ged and I sat outside, drank coffee and talked about where we wanted to go as people. We talked a time about the band and all of that, but mostly about ourselves and the kinds of things that we had gone through over this two-year period we had off. It was great, because we made a connection.

"I went through a whole growth period with Victor," continues Lifeson, "not only as a guitarist but as a songwriter. Having been in the chair behind the console directing it all, it shed a whole new light on what Rush do. I just felt much more confident about the whole process. In a lot of cases, before a record we would have just came off a three-month break, but because of Victor, I played all year and only had a couple of weeks off. I was in pretty good shape as a result."

Lee, on the other hand, shied away from the solo album bug.

"It's much easier to make a baby than a solo album." admits the "voice" of Rush. "But it's been 14 years since my last child, so it was a fairly big turnaround in my lifestyle. It was new, but it was nice to get away from the band. When I leave the band, I'm gone, I can leave the "rock world" pretty easily. I don't want to bring that life into my household, there's a different thing going on there. What I learned on the writing of this record, which I felt was profound, was that this time I didn't have to stay overnight at the Chalet for it to be productive. I love those guys, I see lots of them, but I didn't have to sleep in the same house with them. I commuted. The drive up let me clear my head and I got to listen to tapes of the last day, think about arrangements and stuff. I was happier because I got to sleep in my own bed, see my wife and kids and my life wasn't disrupted. By the time I got to work, I was just so vibed up and ready."

For Peart, the new freedom meant getting back to the "traps".

"After 30 years of playing," he recalls, "I was able to step away from performing and really explore drumming, and it became a revelation for me."

On their return to the Chalet, the band felt that it would be important to find new ways of working.

"In the past," reveals Peart, "Geddy and Alex often 'built' the songs as they went, matching verses and choruses and roughing out the arrangement on a demo. At that point we would all listen to the song, and discuss what was good and what might be improved troth musically and lyrically."

"The difference this time," offers Lifeson, "is that Geddy and I both were on such a roll that we didn't want to break it up. Everytime we started writing something, we started another song. So we got four or five songs into pretty good shape and then played them for Neil. Consequently, he didn't hear anything for about a week, so he was panicking a little. We were very productive but he was wondering if we had a block or something."

Peart says that although he was constantly giving his bandmates new lyrics, the waiting period left him with a lot of practice time.

"I was constantly 'feeding the machine' with more lyrics," says Peart, "and when I needed a 'left-brain break', I could go have a bash on the small practice kit in the hall outside my room."

Geddy Lee, who says that without Peart he would have nothing to sing, figures that Peart's patience is only equalled by his flexibility in collaboration.

"I think I always prefer to begin with the lyrics, to be honest," says Lee. "At the end, it becomes a finer marriage to me. Neil's great to work with because he'll write umpteen songs, and if ten of them make it he's happy with that. He never insists that we use one song over another. And of course, since I have to sing those lyrics, I've got to feel pretty positive about them. He lets me react to them and gravitate to the songs that I feel arc stronger. During the course of a writing day, even though Neil's at the far end of the house, I'm running back and forth every half hour saying, 'Okay, I've got this pad nailed, but this pad is giving me trouble; can you think of an alternative?' Very rarely these days will he be inflexible about changes."

Having written enough new songs for an album, it was time to capture them. To set about that task, the band once again enlisted co-producer Peter Collins, who had also assisted them on Power Windows, Hold Your Fire and Counterparts. The band are unanimously effusive on the subject of Mr. Collins' input.

"I think Peter is the last of a dying breed," pronounces Lee, "which is producers who are interested in nothing but producing songs. They don't want to touch the console, they are only interested in 'is this performance good? Is this song or arrangement good?' If something sounds great he doesn't feel he has to change it. No ego involved. Other times, he'll say, 'that song needs work, let's work on it', or 'you missed the point'. There may be only three or four songs on the album that he kind of tears apart totally, but it's a much better record for that."

"Perhaps Peter's greatest contribution," offers Peart, "is his instinct for pointing us in the right direction."

Lifeson concurs.

"By the time we start recording, we have a really clear idea of what we want," says the guitarist. "It's just a matter of getting in there and playing. The great thing about having Peter there is that he reminds us that the performance is the performance. We tend to get anal about getting it right, but spontaneity really is the key."

"Peter's responsible for making sure that everything's under control," asserts lee. "That allows us to be simply the musicians. I think it's really important when you are playing to be a player, without always having to switch back and forth to be the guy who's judging it."

For some time, Collins had suggested that Peart record his drums at Bearsville Studios, a huge wooden room in Woodstock, New York. This time he finally relented.

Lifeson, for one, was pleased.

"Peter had been bugging us to go there and do drum tracks, and we avoided it for a number of reasons. Where we usually do drums, Le Studio, in Morin Heights, Quebec, is really close to where Neil lives. But the room at Bearsville is an enormous wooden room with high ceilings. It's like a hangar, it's about three stories high - Neil's drums sounded particularly amazing in there."

Lee seconds Lifeson's enthusiasm.

"Damn if Peter wasn't right. Bearsville has this great old Neve console from Pete Townshend's old studio, so I'm like, 'It's the one they did Quadrophenia on, cool!' It was cool until all the knobs started breaking a and everything started buzzing!"

For everything else on Echo, Lee and Lifeson recorded at Toronto's Reaction Studios, a cosy secluded studio whose previous clients include Change Of Heart, Rheostatics, Barenaked Ladies and, er, Anne Murray.

"What we wanted was somewhere private," stresses Lifeson. "We had worked a lot at McClear Pathe, and they have three very busy studios, so you're sharing the lounge with everyone else that worked there. That's fine for corporate stuff and commercial works. But for us, we wanted to have a place that was all our own. And there aren't too many studios anymore that are like that, who could accommodate us, with the kind of sounds we wanted and the size of the room. So we went to Reaction. It worked out great. The people there, like Ormond Jobin, were great and everyone was really nice, so it was a great vibe."

"These days, you don't need the biggest most expensive studio to make a great record," figures Lee. "All the equipment is so standardized, it's so easy to go almost anywhere to make a record. So really, it was the vibe and the privacy factor that made Reaction work for us."

One thing long-term Rush fans will notice on Test For Echo, is a return to the acoustic and electric guitar as focus instrument. Gone are many of the keyboard synthesizer textures of later Rush albums.

'I wanted quite a different character to the way I approached the guitars this time," says Lifeson. "I really wanted to combine acoustics with heavy electrics. I wanted the rhythmic aspect of the guitars to stand out a little bit more. I used it quite a bit as kind of a flavour for the whole record. I think there are only about three or four songs that we used keyboards in, the rest is just guitars."

Lee is happy about the shift back to acoustics.

"I think Alex rediscovered just how heavy the acoustic can be," says Lee. "A really well strummed acoustic can he really heavy, it doesn't always have to be a pretty little sound. Some of my favourite Who records have these huge acoustics. Pete Townshend has always been the quintessential rock songwriter, the Paul Simon of rock."

Was it hard for Geddy to leave out the big synth pads this time out?

"We were going for more of a drier, upfront sound," affirms Lee, "a bit of a throwback to earlier albums. Guitars did the job well. We threw out the paddiness and used keyboards more for counterpoint melodies, and not to just fill up space. There's keyboards on 'Limbo' and on 'Test For Echo', but they're very subtle. I think in one sense we eliminated the textural stuff because we found that it was soaking up the guitar space.

Working with hot engineer Clif Norell, who has recorded REM, Catherine Wheel and Faith No More among others, was particularly refreshing for Lee.

"He was the EQ guy on the record," enthuses Lee. "I know what I want to sound like, so l say 'this is what I want, now go get it for me'. As a result, I didn't use a bass amp on this record. Clif got a really good bass sound using three different direct effects. It sounded more amp-like on record than my amp does."

"He's a Virgo," Lifeson offers, "so he's very organized and kept track of everything. He went after sonic perfection. And because he and Andy Wallace had worked together so much, it made it easier later because Andy knew what Clif had done and what he meant in his notes on the track sheets."

Wallace, a veteran mixer and producer whose talents have graced recordings by luminaries such as Rage Against The Machine and Nirvana, wins the band's respect for turning the finished recordings on their ear, so to speak.

"Andy was able to take all of that music we'd lived with for so long and weave it into new and unexpected patterns," gushes Peart.

"It's his thought process, I think, more than anything, adds Lifeson. "When he got a mix up, he brought elements out of the songs and sounds that I had never thought of before. Everyone felt that way. But he had a reason for everything. He could give you a very concise explanation for it. I was really impressed by that. Later, when I heard it all back I couldn't believe how much air he had left around the instruments."

While Lee shares the group hug for Wallace, he made sure that one particular instrument was audible in the mixes.

"He had to adjust to a band that mixes the bass so loud," Lee says sheepishly, "we always have to break these guys in, but his first mix was surprisingly in a direction that we wanted in the first place. He's got brilliant engineer chops. He brought out a lot of extra dynamics and things that I didn't even know were there. I think the record sounds very different for us as a result."

Of the songs on Test For Echo, all hands are pleased to point out their personal highlights. Naturally, lyricist Neil Peart is proud of al his words, but particularly keen on Virtuality, 'Resist' and the title track, which was written with former Max Webster lyricist, Pye Dubois.

"The lyrics to 'Test For Echo'," explains Peart "give a video-view of this wacky world of ours and offer this tacit response: 'Excuse me, does anybody else think this is weird? Am I weird?' While the answer to those questions may be 'Yes!', it's good to know that you re not the only one, you're not alone."

Alex Lifeson was happy with some new things he tried this time out.

"The choruses in 'Totem' are really interesting. I created a soundscape by using harmonics with a kind of Celtic melody over it that's quite distant. In the song, in terms of dynamics, it's a really beautiful shift. Listening to it in cans, there's this line, 'angels and demons inside my head' that was very visual to me, it's almost angelic. You can sort of see this imagery swirling around. 'Resist' is one of the best songs we've written I knew from the beginning that this was a special Rush song just by the kind of energy that came from all of us when we wrote and recorded it. 'Virtuality' is a nice heavy sort of song, which I really love doing."

Geddy Lee singles out the album's first three songs as faves. He's particularly fond of the "manic quality to 'Test For Echo' - a kind of absurd thread that I like a lot. Nothing makes any sense. I like the fact that there's some nice melody and some confusion and a manic nature, and yet there's lots of space. 'Driven' just from a bass player's point of view. I wrote that song with three tracks of bass. I brought it to Alex and said, 'here's the song; I did three tracks of bass but I just did it to fill in for the guitar,' and he said, 'let's keep it with the three basses'. So I said, 'I love you'. That was really nice to have the blessings of my bandmates to put three tracks of bass on it. I mean, who lets a guy do that in this day and age? 'Half The World' is one of our finest moments as songwriters as far as writing a concise song without being wimpy or syrupy. It's got a little bit of everything; nice melody, and yet it's still aggressive. It's hard for us to write that kind of song, really. You'd have to go back to 'Closer To The Heart' to find an example of that."

And so, it would seem, closer to the heart of each of Rush's individual members.

After over 20 years of playing and recording, topping countless Guitarist or Drummer or Bassist of the Year polls year after year, being named to the Order of Canada and inducted into the prestigious Harvard Lampoon, they have much to be proud of as individuals and even more as a group.

Peart says that the band have reached a new level of respect for each other that signals the beginning of a new Rush after all these years.

"After so many years of apprenticeship," says the drummer/lyricist, "I believe we're finally starting to get somewhere. Together."

"Working together," seconds Lifeson, "especially on this record more than any in the past I feel like we've arrived as a band. There's a quality to the sound, feel and development of the songs that really sounds complete to me. I really feel like we have completed a cycle. Funnily enough, if this record's about anything, it's communication. We communicated on a level that we hadn't in a long time. We've always been very close, but on this record, we all got so much closer. It felt so unified, which is really good. After taking a long break like that, there certainly was a worry whether we still had it in us. I was on such a high after Victor, I really needed to do that for myself. Having that kind of control I wasn't sure if I wanted to go back to the same old thing. But then we started writing and I realized that it no longer is the same old thing."

Gear

Geddy Lee

Basses: Fender Jazz basses (2), a 1972 Maple neck and "One of them has a 'Hip Shot' on it so I can detune to D, which I did on about six tracks on the record."

Direct Boxes: Demeter Tube DI, Palmer PDI-05 speaker simulator, Sans Amp (rackmounted model)

* Note: While Geddy used no amplifier on the recording of Test For Echo, his live rig consists of the following:

Amplifiers: Trace Elliot Quadra 4 amps, GP 12 SMX Preamp, 4x10 cabinets and a couple of 18" speakers

Strings: "I just went back to Rotosound mediums after a long time away.

Neil Peart

Drums: Drum Workshop kit [22" bass drum, 8" tom, 10" tom, 12" tom, 13" tom, 15" short floor tom, 15" floor tom, 16" floor tom, 18" floor tom, (2) 18" bass drums, 14" maple snare, (2) 13" piccolo snares, double bass drum pedal, (2) single bass drum pedals and assorted DW hardware]

Heads: Remo Coated Ambassador (for the toms and snare), Remo Clear Diplomat (on bottom)

Cymbals: all by Zildjian except * - (2) 8" splash, 10" splash, (2) 13" hi-hats, 14" 'A' Custom hi-hat, (2) 16" Rock crash, (2) 18" medium crash, 20" medium crash, (2) 22" ride, 18" China Boy low, 20" China Boy high, *Wuhan 18-3/4", assorted cowbells

Sticks: Pro-Mark 747

Electronics: KAT mallet controller, (8) ddrum electronic pads, (2) shark electronic pedals, S/D trigger

Alex Lifeson

Guitars: Fender Stratocaster, Telecaster, Strat Elite Gibson ES 335, ES 355, Les Paul Standard, Dove PRS McCarty, Artist CE Bolt-on

Amplifiers: Marshall JCM 800 100 watt, 50 watt, 6300 Series, 1960 4x12 Vintage 25 watt cabinets; Digitech GSP 2101 Tube Preamp with Palmer PDI-05 speaker simulator ("The Digitech has different effects and sounds in it which I ran through the Palmer. Then I just knitted that in with amp sound. The Palmer just has really warm filters.")

Effects: Roland SDE 3000 (2), Lexicon 224, Lexicon PCM 70, TC Electronics 2290 DDL (2), TC Electronics 1210 Spatial Expander