Learning To Swing Has Everything To Do With Learning To Rock

By Neil Peart, Drums Etc., September/October 1997, transcribed by pwrwindows

Welcome to the world of Canadian drum legend - Neil Peart. We are going to hear some of his new perspectives on drumming after his exciting rediscovery of rhythm with the inspirational help of his coach Freddie Gruber - friend and mentor to the legendary Buddy Rich. Let's listen in and hear Neil's words of wisdom as told to Rick Gratton and Maureen Brown of Drums Etc.

When I think back to when I first met Freddie Gruber, I realize that it was a wonderful collection of coincidences - it seems like a miracle. After 30 years of playing, I had reached a point where I was a bit restless. Without realizing it or putting it into words, I was trying to reach greater heights. I somehow knew that I had to take up new challenges to keep from going stale.

At the time, I had already known Steve Smith for quite a few years. We had played together on the Jeff Berlin record. I always knew he was a really good player, but I was just amazed at how his musical style had grown. In the Burning for Buddy sessions, everything he played sat well with the band. Yet, it didn't look too careful or staged. I saw a lot of movement, but it was beautifully placed and musically phrased. That's what struck me the most - not his technique, although it was pretty incredible too. I asked him what his secret was, and he said: Freddie Gruber.

During those Burning for Buddy sessions, I had a chance to meet and talk with Freddie. He came across like a lunatic. Dave Weckl told me that he thought Freddie was just a flake, and wouldn't have anything to do with him. But, I was so impressed with Steve's results that I really wanted to try the same thing. I decided to throw everything up in the air and see what would happen. Freddie agreed to have me spend a week working with him in New York. Every day that week, I worked all day long in a small rehearsal room with him.

I played for about thirty seconds, and he watched the way I moved. Actually, he's more like a coach than anything else. People don't understand that. They often ask: "Why would you have a teacher after 30 years of playing?" I tell them that it's the same thing as a tennis player who always has a coach. And "coach" is definitely the right word to use in this instance. He doesn't teach you how to play a beat or a double stroke roll. He just watches the way you move, and tries to find ways that are more natural for you. The more natural you are, the more musical the sound will be. He tries to get everything to flow so all your limbs work together. Oddly enough, this is one area where I have difficulties. I have a problem getting my hands and feet to work together. I'm so uncoordinated that I was never any good at sports! When you have to put together a flowing and rhythmic pattern, it gets complicated if you lack coordination. Freddie was a real inspiration and a tremendous help that way.

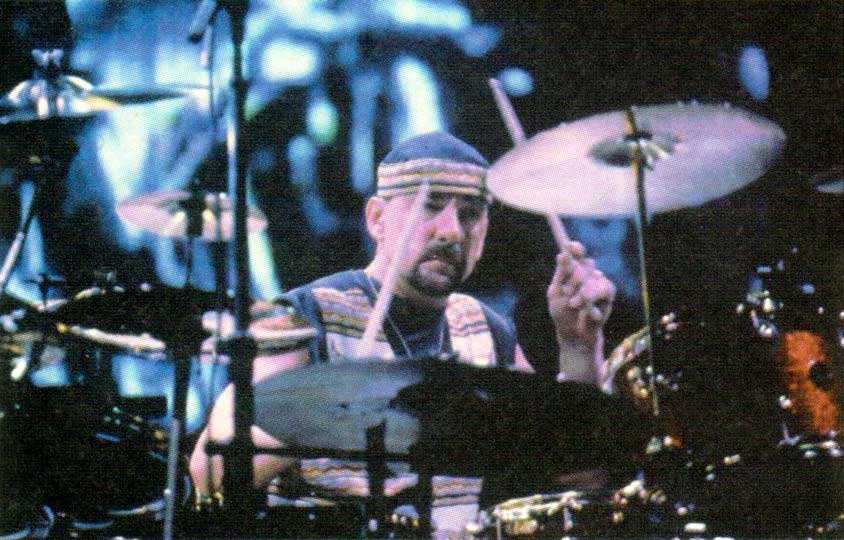

At the time, I was about to start work on a record with Geddy Lee and Alex Lifeson from Rush. I put everything on hold. I told them I needed more time, because I wanted to give these things I was learning a chance to mature. The truth is that I really did throw everything away - everything I had learned before. I started holding the sticks differently, sitting differently, striking the pedals differently... I completely revised it all, not knowing if it would ever come to anything professionally. But, I was just so inspired at the thought of starting all over again. Everything I had ever known was useless, since I had to approach drumming in a completely different way.

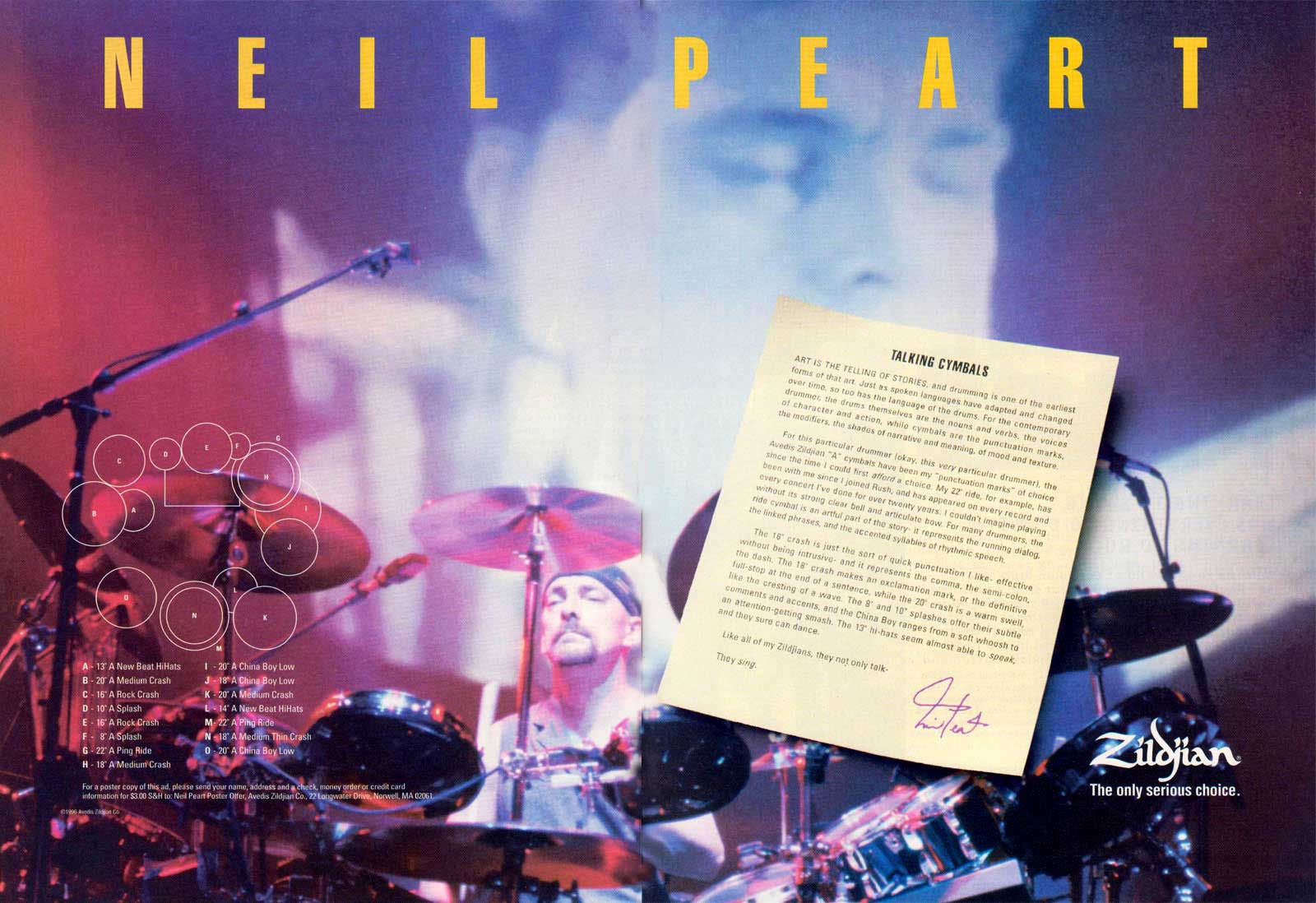

I switched to traditional grip with Freddie, because he said, "Why not try it? It doesn't make any difference in the end." So, I went ahead and tried it. I discovered that traditional grip works in a way that is similar to the whole orbital motion idea. I liked what was going on between the beats, and found that it made the actual back beat feel different. I thought to myself: "Different is good!!!" I stayed with it, and recorded the entire Test for Echo album with traditional grip. When we went on tour, I just chose whatever grip worked for the songs. Some were better with traditional and others with matched grip.

Any time I learn new things as a student, I surrender to the teacher. Otherwise, what's the point in being there? Some days, I would just go through the motions, do the exercises and play around. I may not have been really making any progress, but it's still rewarding since you keep the tools fresh. Every two weeks or so, I would have a day when it would all come together. Everything seemed effortless. Suddenly things were happening, and new avenues were opening up. Very few things in life make you feel as good as that does.

A lot of people don't distinguish between performing and playing. If you go down to the basement and play your drums, there can never be a negative moment. If anything goes wrong - who cares? It's just like people who play catch in their backyard, and think that it would be nice to be a professional baseball player. They're confusing playing a game and performing. The same thing applies to a musician. How many people fantasize about the idea of being a musician and playing for a living? Of course, when I am down in the basement or at the rehearsal studio, I am playing just like anyone else. But when you're on stage or in the recording studio, it's a different story. Then you have to perform. There is a certain level competence that you come to expect from yourself. Delivering that is no small feat. A lot of musicians believe that you're only as good as your as your last performance. I certainly felt that way when I was on the road. I realized that each time, I got another chance to go up there and do it again. That's part of the subtle addiction of performance. Every time you play, it's a fresh round - another chance to get it right.

When we were recording the Test for Echo record, Geddy came out just after I recorded the title song. He told me how good it sounded. I said that it was hard to imagine that two years ago, I could not have played anything in that song. He found it really hard to believe, because a lot of it sounds deceptively simple. Although I might have been able to imitate the sound, I would not have explored it in the deepest sense. I probably wouldn't have formulated it the same way. And, I would not have been able to articulate and deliver the sound in that way from a deep time sense.

Working with Freddie made me feel the pulse of things that I had never consciously sensed before. He helped me apply that feeling to my work. It gave me much more control over my playing in terms of tempo, and the looseness or tightness of my grip. I learned how to push hard to make the sound more aggressive, or relax and make it sound more comfortable. I suppose that every craftsman strives to master his tools. Freddie helped me do that, which increased my level of confidence.

We just finished a tour...I think we did 67 shows. I have never felt that kind of confidence or control while playing. I was really in tune with my instrument, the band, the tempos and dynamics. Any ups and downs I might have experienced during the tour were not related to my playing. Most drummers spend many years being insecure. I know I was for a long time, and I'm glad to get beyond it now. I give Freddie credit for a large part of that. I think of him as my 70-year old brother.

By the way, Dave Weckl ended up taking lessons from Freddie Gruber as well. After Dave practiced what he had learned, he called Freddie back and said, "You're not a lunatic after all!!!" You know, it takes a whole day to get a half-hour lesson out of Freddie. That's the way he works. I love his stories, and I love the man.

Producing the Burning for Buddy sessions was tremendously challenging and very rewarding. I found myself falling even deeper in love with the music all the time. I developed more and more respect for Buddy Rich as a musician and drummer. It was really hard for me not to watch the other drummers when we recorded the Burning for Buddy sessions. I would sit behind one of the speaker monitors so I couldn't see the drummers. I just closed my eyes and listened, because I didn't want to see what they were playing.

It wasn't until the Burning for Buddy video was made that I actually saw the guys play. When a new drummer would come in for the first take, I would usually sit in the studio between the drummer and the band. I would listen to the sound as if it were an entity unto itself. Then, I would move back into the control room, and step into the professional role. For the most part, I just had to keep my eyes closed. I knew that if I watched them, I would have totally ruined my job. In that sense, I was much more of a supervisor, organizer and motivator. When I recorded my own tracks, I basically learned by ear - using Buddy's version of the tapes. For months, I had been playing along with Buddy's versions of those songs. This was my first opportunity to step away from that, and really work with the band as a whole.

When I covered Buddy's career, I looked into every detail of his work - in small group situations, with vocalists, and with his own big band. I realized that his different approaches were rendered with consummate mastery and taste. To hear him play brushes on Here's that Rainy Day or play with Nat Cole in the 40S was truly a pleasure. I was constantly impressed with just how good he was.

Buddy Rich knew how to change with the times. I have always believed in the expression: "Out with the old, in with the new." And, he personified that in his work. If music styles changed, so did he. He never resisted change; he simply changed with it. He once said, "If people come to see me expecting a Tommy Dorsey revival, they're going to be disappointed." He always wanted new arrangements and new challenges. In fact, he didn't have a standard repertoire at all. It changed constantly as the times changed.

In the Burning for Buddy Vol. 2 video, you see Buddy in a live performance when he is on the verge of a heart attack. He was playing an opening act and back-up band for Frank Sinatra down in Puerto Rico. It was incredibly hot, and he was wearing a tuxedo. I think he must have been in his late 70s by then. During his performance, his daughter Cathy realized that something was wrong. She could tell that he wasn't well, but he was playing brilliantly and relentlessly. He did not cut his performance short, but went back to the dressing room right away where he collapsed and had a heart attack. Cathy said that he called up the next morning and asked, "So, do you want to go to the pool?" It's just the kind of guy he was. He didn't care if he died; he only cared if he didn't play well. That is certainly an inspiration for any musician!

Rush has two things on the back burner right now. We have been recording the last two tours and we would eventually like to put together a live anthology. At the same time, we are eager to get started on new work. We have talked about starting the new studio album at the beginning of next year. In any case, we are working on getting both projects going right now, since they are so promising.

Aside from my work with Rush, I have also been writing a book based on our tour. It's a combination of my motorcycle adventures around the back roads of America and rock tour experiences.

I think that if I combine the two in the end, I'll call it Landscape with Drums. [Webmaster note: Landcape with Drums was later the subtitle given to Roadshow: Landscape With Drums, A Concert Tour By Motorcycle, published in September 2006].

Note: We would like to extend our heartfelt condolences to Neil and his family upon the loss of his 19-year old daughter, Selena Taylor, who died in a car crash on August 10, 1997.