The Different Stages of Rush

By Jeffrey L. Periah, Guitar Shop, March 1999, transcribed by pwrwindows

Guitarist Alex Lifeson Reveals The Secrets Behind A 25-Year Legacy

For hardcore Rush fans, 1997s Test for Echo tour must have seemed too good to be true. Each three hour performance offered music representing various periods of the band's illustrious career. Highlights included a complete rendition of the landmark "2112," the first time the trio had ever played the grandiose story-song in its entirety, as well as material from the band's ambitious yet earthy '97 album, Test for Echo. After a three-year touring hiatus that saw guitarist Alex Lifeson, singer/bassist/keyboardist Geddy Lee, and drummer Neil Peart explore individual projects, the band was clearly back as a cohesive and power unit. Fortunately, Rush taped many of the shows on that tour, and that material inspired the band to release its fourth live album, Different Stages.

Just as the Test for Echo tour spanned Rush's 25-year recording career, Different Stages offers a retrospective look at the progressive, hard-rocking Canadian trio on three CDs. Besides serving up choice cuts from the group's 1997 and 1994 tours, the package also includes a special bonus disc that captures a blistering gig played at London's Hammersmith Odeon in 1978. From adrenaline-soaked numbers like "Bastille Day" and "Something for Nothing" to a mesmerizing performance of "Xanadu," the '78 disc showcases Rush on a particularly incendiary night. But raw intensity isn't just limited to the Hammersmith Odeon show. Lifeson says the band wanted to release a set that captured the energy and grit that's always been a natural part of their live gigs-qualities that he feels were not conveyed effectively enough on the overly produced 1981 album Exit ... Stage Left.

The past two years have been an extremely sad time for Rush, particularly for Peart. In June 1998, his wife, Jacqueline, passed away after suffering a cancer-related illness. And in August 1977, his daughter, Selena, was killed in an auto accident. So for now, Rush has no immediate plans for recording or performing.

Guitar Shop recently spoke with Lifeson about Rush's dynamic, multi-faceted work. By revealing many of the twists and turns the trio has encountered over the years, Lifeson helps us to understand the different stages of Rush's fascinating history.

What was special about the way you recorded and selected the 1997 and 1994 material on Different Stages?

Being able to record 45 or so shows on each of the last two tours just gave us so much stuff to pick from. That alleviated a lot of the pressure and allowed us to just play without thinking about being recorded. As it turned out, most of the songs are from a gig in Chicago at the World Amphitheater on June 14, 1997. Everything worked well that night: our playing, the audience, and the venue's acoustics.

What was significant about the 1997 Test for Echoes tour?

It was the first time we did ''An Evening with Rush." At first, we kind of battled with that idea because we'd always felt it was important to provide an opportunity for an opening act. But after 25 years, we figured that maybe it was time we played a whole show ourselves. It allows us to perform an extra hour's worth of material. On previous tours, it was really tough for us to decide what we were going to play and how we would cover all tile bases, but having three hours to work with made it a lot easier to include some longer pieces like "Natural Science" from Permanent Waves and all of"2112"-pieces that were really important for us to play live.

How do Rush's live releases - All the World's a Stage [1976], Exit... Stage Left [1981], A Show of Hands [1989], and this new set - differ?

Before we put out the first live album, we'd been touring a lot; we did about 250 shows a year. We were a live band-that was our whole thing really We loved recording in the studio but we were much different on stage. We wanted to have some record of that, and All the World's a Stage certainly sounds just like the concerts did: very raw and explosive. With Exit... Stage Left, we got a bit fancy in the studio and made it sound more like a live studio recording. We cleaned it up so much that the recording didn't have, at least for me, the same kind of energy that a live show really does have or should have. A Show of Hands was a step in the right direction, but I don't think we really achieved it with that record either. When you put this record on, however, you feel like you're there. You can hear people talking in the first few rows and it's got toughness, body, bottom-end, and plenty of energy.

The third CD of Different Stages showcases a 1978 concert at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. The show, in support of A Farewell to Kings, certainly displays the raw intensity Rush was capable of back then.

We were younger and full of energy. There was a whole different approach and attitude towards playing. Our tempo would wander sometimes and we tended to speed things up. And obviously Geddy's voice had a real growl and tear back then. It's interesting to hear the contrast between the way he sang during that gig and his vocals during the '94 and '97 tours.

What made you pick the Hammersmith Odeon show specifically?

We came across it when we were clearing out a tape storage room. Geddy had a bit of a cold when we did that gig and after hearing the tapes initially, didn't feel that great about his singing. So the tapes were put away and we basically forgot about them. But when we came across them again recently, we knew we had something that was very cool. In the past, we've closed periods in our development with live albums. But this time, by having the stuff from 21 years ago and because we covered material from the various periods of Rush during the '97 tour, it took a different complexion. It became more of a retrospective release.

As showcased on Different Stages, Rush-for the first time in its history-played the complete "2112" throughout the 1997 tour.

It's one of most important pieces in Rush's history. When we first toured "2112" [1976], we were still primarily an opening act. We never had an opportunity to play the whole thing because there was so much other material we wanted to play. But having that extra hour on this last tour gave us the kind of time we needed to play the whole thing-and it was immensely satisfying.

What part of "2112" was especially satisfying for you during the 1997 tour?

Certainly the section entitled "Discovery." I wanted to keep the whole concept of discovery-of finding an instrument and fiddling around with it until you achieve a sound that you want-really quite open from night to night with improvisation.

The albums that preceded 2112-Fly By Night [1975] and Caress of Steel [1975]-featured several lengthy cuts like "By-Tor & the Snow Dog" and "The Fountain of Lamneth" - pieces that contained grandiose elements that would show up more prominently on 2112.

We were very influenced by the progressive rock movement from England, and on Fly By Night we wanted to try extended pieces like "By-Tor & the Snow Dog" with which we could really stretch out and write in a more storytelling way. It was a kind of testing ground for us. And Caress of Steel-which was a hugely unpopular, commercially unsuccessful record-was actually a really important record for us to make because we learned a lot with it. Without having done "The Fountain of Lamneth," we never would have made "2112." But the Caress period was also a particularly difficult time in the band. We were pretty new to the scene, and I think support for us was waning a bit. The record company was a little bit nervous and unsure of whether we could make a commercially successful record that would buy us the kind of freedom we needed. But 2112, of course, did. It brought us the freedom to do things the way we believed was right. And we've been able to maintain that right through 'til now.

Over the years, what have been some of the main challenges of playing in a trio, especially one that's been tackling such technically complex material?

Well, right from the beginning I've always felt that the guitar had to provide as much "width" as possible in terms of chordal structure and parts being played, sometimes by keeping open strings ringing, playing suspended chords, and doing other things that would give the impression of either another guitarist or another instrument creating a sympathetic melody. I think that's really been the hallmark of my style and how I've tried to develop as a player in Rush. And it's always been a terrific challenge to play with Geddy and Neil. Even during the early days, Geddy was the kind of bass player who wasn't locked into a conventional style. He was all over the place. He played his bass like a guitar on a lot of songs. And Neil would have this intricate, multi-rhythmic approach. The two of them would play like mad all the time. That's an interesting kind of environment to be in for a guitarist. The tendency is to try to play the same way and try to be all over the place, and we've certainly had our moments like that. But there are also times when the guitar takes a more melodic approach and allows the rhythm section to go wild.

Who were some of your major influences as a guitarist?

I've been influenced by many players over the years. Certainly, Jimmy Page was a big influence when I was younger. I met him for the first time last summer when he and Robert Plant played here in Toronto, and it was a thrill for me. Jimmy represented everything I wanted to be as a guitarist, from the style of play to the looks. But over the years, many other players have influenced me. For instance, I've always loved Eric Johnson's style. He's also a beautiful person, and that's a great thing to be influenced by as well.I also love listening to Adam Jones of Tool play. He's great. In fact, Tool reminds me of an earlier kind of Rush in the way they structure parts-how they "morph" from one section to another and use bridges as whole sections. Their last record, Aenima, is my wife's favorite album.

Did you make any changes to the way you set up your sound during the 97 tour?

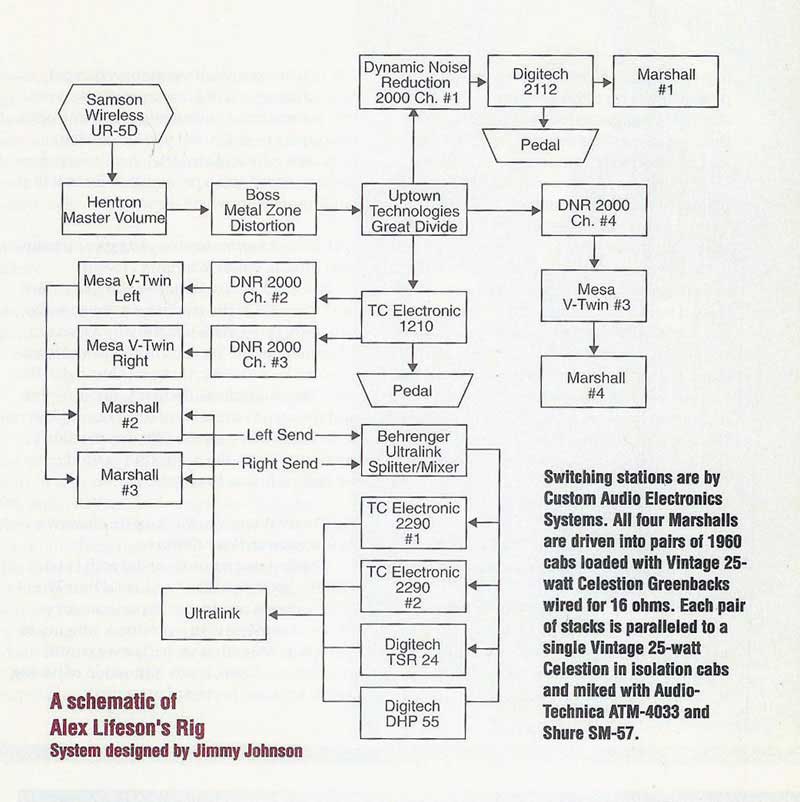

Yes. I had three different set-ups that I could use at any time or at the same time, which gave the impression of there being more than one guitar being played. One was comprised of my main stereo effects rack; the second one is a special effects rig run by a Digitech GSP 2101; and the third one goes straight into a Marshall head with nothing in between. The custom-made, electric/acoustic hybrid guitars that Paul Reed Smith built for me allowed me to include acoustic work in the midst of electric guitar passages, which added more depth and more layers to my guitar work. All the acoustic stuff on "Closer to the Heart," "Driven," and "Nobody's Hero" was played with the PRS's. However, I played the opening of "The Trees" from Hemispheres [1978] with a nylon-string classical Ovation.

Many regard Hemispheres as one of Rush's most stylistically ambitious albums.

It was a pretty difficult record to make because of the material, and the way it all knitted together. Since it was a concept record, we wanted everything to be tied together. And the execution was another thing because we didn't record our parts separately. We all went in and recorded the whole thing at the same time. Neil was set up at one end of the studio with baffles around his drums to enclose him from my amps, and Ged was across from me. And we would play the pieces until we got them right. (Incidentally, "Xanadu" [from A Farewell to Kings] was recorded the same way. I remember engineer Pat Moran sitting in his chair with his jaw dropped as we recorded that. He was impressed that we went in and did a song that quickly that was that long and that intricate.)We didn't have a lot of time to prepare Hemispheres. When we started it, we had just come off the road. We had about 10 days off and then we went to the U.K. to start working on the record. But we hadn't written all the material yet, only a few pieces here and there. We recorded at Rockfield Studio, a little farm house in Wales. We booked three weeks of rehearsal time at a barn down the road from the studio. We worked every single day and finished on the last day at about seven in the morning-after having worked all night. Then we started recording the next day. We had one day off for the five weeks or so that we recorded. We were so burnt out. And when we started mixing, it wasn't coming together, wasn't sounding right. We weren't happy with it and we couldn't tell anymore where we were going with it. So we took a week off, and everyone went home. You have to understand that to take a week off in the middle of recording, back then, was something you just didn't do. But we felt we had to. After the break, we moved into Trident Studios in London to mix the record and everything seemed to finally come together.

Were the Moving Pictures [1981] sessions as difficult?

First of all, Moving Pictures-along with Test for Echo-was the most enjoyable record we've ever made. While working on it, we all felt like we were trying new, different things. We kind of changed the way we approached songwriting and presented our music. We were doing more compact songs, like "Red Barchetta." The structure of that tune was great. It became almost a visual thing in which you can see the car racing. And melodically it tells a story very well.We recorded Moving Pictures at Le Studio in Morin Heights, Quebec, which is situated on a hill overlooking a lake. The lake is about four acres around and its far side borders the Laurentian mountains. We set up some amps and mics out in the parking lot. It was during the winter with lots of snow on the ground. As it turned out, we recorded some great guitar stuff out there. I remember working on "Witch Hunt" at 3 o'clock in the morning and these amps are just screaming. We were using the mountain as our natural delay. There was a really cool, haunting sound to it; every reflection was quite different depending on how it hit the mountain and trees.

The beginning of "Witch Hunt," if you recall, features a mob scene. We recorded that on the main road leading to the studio, also late on a cold winter night. We had a bottle of scotch to keep us warm. We did about eight or 10 takes of this mob grumbling and building in intensity and anger. The first few takes we kept quite real. But by the ninth or tenth, we were all throwing in lines you'd hear in "Popeye." If you listen closely, you can hear some very funny stuff. There was a particular vibe to the way we recorded Moving Pictures that was a lot of fun, and that's reflected in the way the album sounds.

Signals [1982], the studio album that followed Moving Pictures, also entered new sonic terrain.

Signals has a completely different character from Moving Pictures. And for me, Signals didn't quite hit the mark in terms of songwriting. That was the last record we did with coproducer Terry Brown. Terry was always quite involved in the whole aspect of putting together a Rush record; besides being the coproducer he was often involved in the latter stages of arrangements. During Signals, I think we needed more feedback from him and we weren't quite getting it. The whole area of keyboards was becoming a bigger part of our music. We were starting to develop more paddy sounds that took up a lot more space, and these sounds vied with the guitar in the same sonic area. I remember it was a real struggle to place the guitar where it should have been sitting, and to get the guitar and keyboards to a point where they would sound separate, yet together. For me, there are many moments on Signals where the guitar was short-changed. "Subdivisions" is a perfect example-the guitar is almost invisible. But it was a sonic issue, not a personal thing. We were very unified in direction and it was important for us to explore this new keyboard-laden area of our music.

On Grace Under Pressure [1984], which followed Signals, keyboards continued to play a big part of Rush's sound.

Yes they did. And Grace Under Pressure was, by far, the most difficult record for us to make. We worked for about four months and had only one day off. We were so drained by it-and talk about grace under pressure-it was just amazing that we managed to get through that kind of pressure with the grace that we exhibited. It was very tough and often depressing to make. But you know what? After adversity and struggle, there's a passion on that record and a particular color to it that really represents where we were at.

Did you encounter similar struggles on your next album, Power Windows [1985]?

Not at all. Power Windows was like a vacation. We were in the studio for a few months with that, too-that's just the way we recorded in that period. We took our time and wanted to make sure everything was just right. But with Power Windows, there was an "up" vibe and the record was a lot of fun to make. We were really well-prepared for it as we didn't want to get in to the same kind of drudgery we had with, say, Hemispheres.

For Power Windows, Rush again enlisted a new producer, Peter Collins.

The first two records we did with Peter Collins, Power Windows and Hold Your Fire [1987], were a whole new experience for us. We were working with a producer who made us explore areas that we had never considered before. Again, it was a situation of having a rich, intricate keyboard presence.

How did you approach your guitar work on those albums?

At the time, I was going for a brighter, cleaner sound that it would cut through a lot of the keyboard stuff. It brought about a noticeable change in my sound.

The guitar work on "Manhattan Project," from Power Windows, seems reminiscent of Andy Summers' work.

Yes it does. And I think his influence is evident on a lot of Rush's '80s material. He had a relatively thin sound but it was always very present. And there's a confidence and a sense of humor in his playing that probably mirrors his personality, not that I've met him.

But on subsequent studio albums the band returned to a bolder, heavier guitar approach.

In retrospect, what I really like to do is just crank up the amp and be fat and rich and hard and heavy and edgy-that's what I really like. With Presto [1989] and Roll the Bones [1991], we were moving in that direction again. And that's what we ultimately moved to on our last two studio records, Counterparts [1993] and Test for Echo. We realized that the three-piece-guitar, bass, drums-is really what we're all about. We thought it was time to go back to that central energy.

After Counterparts, Rush took a three -year break.

It was nice. We hadn't had a break like that in our whole history and everybody went and did other things. Geddy and Nancy had a baby girl and I did my solo project Victor, so it was a great opportunity for us to separate ourselves from Rush and get into other things.

Was the future of Rush ever in question after Counterparts?

Nope. As we got more into other projects, the break did become longer and longer but there was no question that we would get back together. It was just a question of when since everyone was having such a good time doing other things.

The break seemed to revitalize Rush, especially considering how fresh and inspired the band sounds on Test for Echo.

We came back with renewed enthusiasm and we were excited about working together again. When we arrived at Bearsville Studios in Bearsville [NY], Ged and I spent a couple of days just talk.ing about what we had discovered during our break. There were some questions about direction and things like that, just because we hadn't seen each other for a while. But once we got through that little soul searching period, we dove into the work and everything carne very quickly and satisfyingly.

What's the overriding theme on Test for Echo?

It deals with communication: how we can communicate and the things we communicate about. And how we look for deeper communication in our lives.

Any plans for a new studio album, or is that prospect too premature?

It's too early to tell. With the live record just out, it buys us a little bit of time, especially in view of Neil's tragedies over the past year and a half Considering those tragedies, it's been a really difficult time for us. The important thing right now is for Neil to be able to live again. We're providing support for him while he starts rebuilding his life. Nothing else matters other than to get him back up again. And the progress has been positive but slow. We're just waiting for our friend to get better and then we'll move from there.

Getting Closer To The Heart Of Rush...With Geddy Lee

Rush's vocalist/bassist/keyboardist looks back on the band's history:

The 1978 London Hammersmith Odeon show featured on Different Stages sounds impressive. Can you discuss how your bass work interacted with Alex's guitar parts during that period?

I don't often think about the interaction between the guitar and the bass in that period. I thought of myself much more as part of the rhythm section, and Neil and I would try to create asolid and melodious kind of foundation for Alex to ignore [Iaughing]-as most guitarists often do. But as for Alex and I, we were still learning how to balance our parts in that period. Our music was more overtly complex, as if "now, we're being complex."We thought of ourselves very much as "players," and not as much as writers. We would go through parts where we would try to be complex; sometimes Alex and I would play the same part together and then try to bridge it with some dynamics, maybe with Alex breaking into a chordal thing.

What was really significant about "2112," considering you played that piece in its entirety on the 1997 Test for Echo tour?

It was the first piece of music that we wrote that we could say had a "Rush" sound. Before that there were things that were Rush-like, but not totally successful. "2112" was the first plateau for our band. You listen to that and say it doesn't sound like anyone but us. It was clarifying in the sense that we knew what we could do and that it was what our sound should be.

While the piece "2112" is quite an achievement, the 1976 album also featured several outstanding shorter tracks like "The Twilight Zone," "Passage to Bangkok," and "Something for Nothing."

When we had just about finished the album, we discovered we had room for one more song, so in 24 hours, we wrote, recorded, and produced "The Twilight Zone." I'm also particularly pleased with "Something for Nothing," especially on the Hammersmith side of the live album. I was happy to bring that song back. Songs like that made that show pretty interesting.I think it's always been a bit of a battle between writing the longer and shorter pieces. In a sense, "2112" was broken up into individual shorter pieces that stand on their own, yet they're best appreciated in the context of the whole piece. For Hemispheres [1978], even the shorter pieces like "The Trees" were long [laughing]. That was the mode that we were in back then. Hemispheres was a very technical album and an exceedingly difficult one to make, maybe the most difficult record we ever made.

Throughout the history of Rush, you've altered your vocal styles a number of times.

I think my singing has changed radically throughout the years depending on the style of the album we were writing. I kind of shaped my voice around it. And if you listen to the Hammersmith show, for instance, you can hear that it's pretty intense, high pitched, and very often out of control. I'm struggling abit in that song to warm my voice up. It's the opening song of the night and you can hear a battle between energy and pitch. Through the years I've experimented alot with my singing, in melody writing, and layering and harmonies. The range of my voice and the keys that I sing in have changed alot since the early days. Fortunately, we're still able to pull alot of that early stuff off live.

Who were some of your vocal influences?

I used to love the singing of Jack Bruce, Roger Hodgson of Supertramp, of course Robert Plant-he was a big influence in the early days-and Jon Anderson of Yes. I went for those sopranos for influence.

And what about bassists?

Jack Bruce again, Jack Casady of Jefferson Airplane and Hot Tuna, and later on, Chris Squire and John Entwistle.

Your vocals were especially strong on Moving Pictures [1981].

Everything kind of came together on that album. To me Moving Pictures was like 2112 in the sense that before it, we'd been trying to move in a slightly different direction, and it all kind of came together on that record. There was more consideration to what key I was singing in and the quality of the recording was at alevel above previous ones. It was as if all the experiments of the previous four or five albums paid off. But you never know when that's going to happen; it just kind of all comes together. It's like the accumulation of experjence eventually pays you a dividend. It's a natural but unpredictable arrival point in your growth as an artist.

Were any particular tracks on Moving Pictures especially difficult to record?

We had ahell of a time recording "Tom Sawyer." We had to work hard getting definition between guitar and bass because the bass was so aggressive-there was so much top end to the bass, and the guitar was very often playing in asimilar range. It was one of those songs that didn't come together easily. And in the end, what we pulled off was really surprising because I didn't have that much confidence that the song was going to be any damn good [laughing]. Who knew?"Witch Hunt," on the other hand, was alot of fun to do. However, one of the days we recorded it, I remember going back into the studio and being shocked because it was the day John Lennon was assassinated. I'll always remember that.

Any thoughts about "Red Barchetta?"

I'm really proud of that song. We loved it right from the beginning. It has a nice momentum from beginning to end and has just about all the elements that I like in a Rush song. It has a nice brisk pace and it has quieter moments. It also has Alex wailing on the guitar. And it has a nice controlled dissonance in the riffing, because what Alex and I are playing together in those heavy riff sections is kind of wrong. Certain notes we're playing shouldn't have any business being played together, yet it all seems to work. The interaction between bass and guitar really came together on Moving Pictures, and "Red Barchetta" is a prime example.

Was Moving Pictures a big departure from Permanent Waves [1980)?

It was a sort of consolidation. If you look at it objectively, it's quite adifferent album from Permanent Waves, although Permanent Waves is still one of my favorites. It's complex but it's kind of loose in away.

Did you use a lot of samples to enhance and complete your sound during the 1997 tour?

We generally use a lot of technology on stage. We use a lot of samples and sequence triggers throughout the entire show, but none of it is controlled by anyone other than us on stage. That still keeps it, as far as I'm concerned, in the realm of performance. It's, mostly textural things that we sequence. For example, I'll take a few chords of a keyboard passage and loop them and then we can trigger them from my foot pedals, Alex's foot pedals, and Neil's drum triggers. Whenever we feel there's a background sound missing, one of us can carry it in.

It must be quite a challenge to play your material on stage.

Oh yes, but that's a good thing. That's probably why Rush is still here. Because our music isn't easy to do. And you try to achieve perfection but perfection is never possible. The whole reason people have a vision . in their art form is because it's really hard to make things perfect in life, so you try to do it in your art, as I believe Woody Allen once said-and I think it's very true. As time passes, you learn there's always an element that's completely uncontrollable in your art, and that makes art exciting-the element that's not possible to plan out, or control.