Speed Freaks

By Philip Wilding, Classic Rock #61, July 2002, transcribed by Dave Ward

After 20 years of success, in 1997 Rush were derailed by a tragedy that almost spelled the end of the band. Now they're back on track. But for how much longer? Classic Rock charts the strange story of Rush. Smoke and mirrors: Philip Wilding

GEDDY LEE AND ALEX LIFESON ARE SITTING AT THE BACK OF Geddy Lee's kitchen, their faces lit up by the pale light coming from a computer monitor. Both men are leaning forward on their stools, peering intently at the screen, though all it affords them is a distorted reflection of themselves: two large, goonish heads made grotesque in the slight dome of glass.

'Rivendell' (1975) plays from the small speakers set out on the worktop before them, they both nod and smile... 'By-Tor And The Snow Dog' (1975) thumps hurriedly past, they both nod, lower lips jutting out in contented surprise... 'Distant Early Warning' (1984) has them cocking their heads like dogs waiting for a biscuit... 'Manhattan Project' (1985) affords them brief, self-satisfied smiles.

They jot notes, reminisce to one another as each song plays. Then they get to 'Finding My Way', from their self-titled debut album of 1974. Both their mouths drop open and then break into smiles. "Hey, buddy," says Lifeson, punching his friend and bandmate genially on the arm, "try reaching any of those notes ever again." They then both buckle slightly with laughter, and Lee reaches forward to turn down the volume on the speakers.

The last time Rush toured was for 1996's 'Test For Echo'. Discounting the idea of a support band, they instead opted for an evening with Rush: a three-hour show split into two halves with a 15 minute break in the middle. Toying with set ideas in rehearsals in upper New York State back then, it suddenly occurred to them - they're not sure who came up with the idea first - to do something that as a band that they'd never done before: play their album '2112' live in its entirety. [Errata note: They did not play the entire album '2112'; they played only the first side.-ed.]

"It really was: 'Fuck it. Come on, let's do it,'" says Lee (Lifeson says the same thing almost verbatim), now 48 though he looks about 10 years younger. "We'd never done it all before, we've never had the time. We said let's do something different, let's bring back something important to our history, so we agreed to have a go at '2112'. And when we started rehearsing it it was really funny. I said: 'I ain't singing these lyrics, and I certainly can't sing this high.' So we detuned it for the tour, which made it easier for me to sing. And something happened after we started playing it; it was just so much fun. it was like the spirit in which the song was written came back - that passion and that intensity."

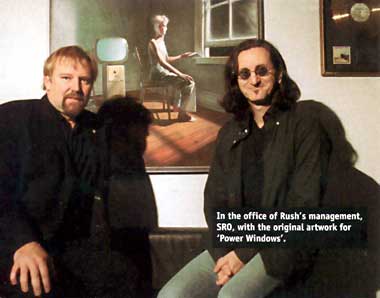

The SRO management offices are on the edge of an area of Toronto known as Cabbagetown. It's early May, but it's still cold down in the basement meeting room. On the walls hang various gold discs, a large unframed black-and-white portrait of Rush - taken sometime towards the end of the 80s, judging by the band's haircuts and Neil Peart's bandanna. Against one wall are the giant dice from the 'Roll The Bones' stage set, and directly above the low glass table at which we're seated is the original artwork for the cover of the 'Power Windows' album - the gawky teenager with a remote control held loosely in one hand.

"Oh, doing '2112' live, that was great," says Lifeson, sporting a neat blonde beard and his Order Of Canada lapel badge. He shifts awkwardly in his seat, the squat chrome and black leather chairs we're on having us both craning forward as if suffering chronic back pain. "On other tours we've left out a piece here, a piece there, but doing a three-hour set we finally had the time. The fans loved it, it was a real special moment in the set. It was so much fun to play too, it was a real stretch for us. When we did 'Discovery' [where the story's protagonist finds an acoustic guitar and learns to play it] every night, that became a little spot where I could show off or just do what I wanted, and that was great. I remember when we did the whole thing in rehearsal the first few times, we were laughing and going: 'Is this really going to work? This is 20 years ago, come on, guys.' [laughs]. But it started to slowly come together and on the tour it became a very powerful point in the set - it closed the first half of the show. We come off with everything smoking away. 'We have assumed control,' he says, imitating the booming voice at the end of '2112', then laughs uncontrollably. "It felt really good."

The success of transforming '2112' live has meant that when Rush begin their latest tour in America in June, they intend to drop long-standing live material like 'Closer To The Heart' and introduce songs that they haven't played live in years - or in some cases ever. They remain tight-lipped over what might or might not make the set (it's another three-hour-plus show), but their enthusiastic surprise at reacquainting themselves with their old albums promises that there will be more than a few surprises.

"We've dropped a lot of stuff from the set that we've been playing for years, and that was a tough decision, but this felt like a great opportunity," says Lifeson. "We've dropped 'Closer' - and we've done that forever. Doing '2112' opened us up to that a little, for sure. When Geddy and I sat down and went through our records and tried to pick out songs, that was really strange, because we haven't heard those records in years. It was surprising, because our memory of what was on, say, 'Caress Of Steel' [1975] was much different to how it really was. I always thought that they sounded a little small and dinky, but they stood up pretty well.

"It comes down to good and bad songs, I suppose. We were surprised by how intact the songs were. My recollection was that they'd all be bitty, but there was a good flow to most of the material, maybe more so than in the last 10 or 15 years. An odd experience."

"The only problem I have listening back to some of the old stuff is that some of it is too repetitive for me and it doesn't hold my interest," says Lee. "I threw the music on the computer and we were listening to these songs and saying: 'Do you feel like playing these songs again?' you know. And, honestly, I haven't listened to this much Rush material ever.

"It was funny. A lot of things stood up, weird songs sounded great to me - like 'Rivendell' ('Fly By Night), of all the stupid things. I listened to that, and thought what a sweet little song, it's about five minutes too long and very repetitive, but it sounded well-constructed and it really captures that little melody. And there were moments of 'Power Windows' [1985] I was very impressed with. I think that's an underrated Rush record. 'Roll The Bones' [1991] doesn't sound up to much sonically - I wish I could record all those songs again - but I think the songs themselves are really good. I was really shocked at how odd 'Presto' sounds. There's a very mature attitude towards songwriting on there, which I guess is the frame of mind we were in."

'Grace Under Pressure' (1984) is a stormy time to me. That's what that record throws up when I hear it. I've always said that Rush records are time capsules of our lives, but I didn't realise how true that was until Alex and I sat down. They really reflect who we are and what we are like and what we were feeling. So you listen to 'Fly By Night', and I can't listen to some of those things. We listened to 'Caress...', and I loved certain songs like 'I Think I'm Going Bald'. 'The Necromancer' just doesn't stand the test of time for me, but parts of 'The Fountain Of Lamneth' did, strangely. 'Hemispheres' (1978) sounded amazing to me, too. I remember that was a very, very difficult record to make, but it was worth it. We went into the studio in Wales and we had nothing written, we wrote it as we went along and it was very ambitious stuff: long tunes, complicated time signatures, and really tough to mix - a bit like 'Vapor Trails' in that last respect."

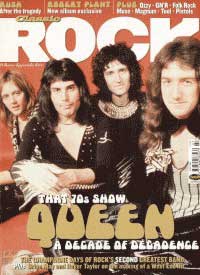

RUSH RELEASED THEIR FIRST ALBUM IN 1974, SELF-TITLED, and with portrait shots on the back of the sleeve that can best be described as monstrous. Gene Simmons of Kiss, who the band supported on numerous occasions, often referred to them rather archly as Led Zeppelin Junior. And, honestly put, he was right. Rush were all exasperated yowls and young man's excruciating gestures; the album, however, was a good one and promised much. And, in fits and starts, they fulfilled that promise. 'Fly By Night' was a commercial and critical success, 'Caress Of Steel' its near exact opposite.

"Oh yeah, 'Caress' was a real dud, commercially," says Lifeson now, with a smile full of hindsight. "There was a real concern from everybody - management, you know. We were hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt at that time, and that was an awful lot of money then. It wasn't really until 1979 that we finally cleared our debts, so management had made a big investment, and the record company was wondering if we should be making records like our first record, all of that stuff. And we said we're going to make this record and if we go down in flames then at least they're our flames [laughs].

"Fortunately, '2112' was just the right record for us at just the right time, and that bought us our freedom. After that the record company never said a single word about the way we did things. But we'd never have made '2112' without making 'Caress'. That was our test record for what we wanted to do, it really was."

You can hear that it's true. Evocative, ambitious themes and arrangements were all prevalent throughout 'Caress', even if the grand execution or the songwriting were lacking. As Lifeson so rightly states, with a concept album as their commercial jumping off point they could quite arguably go whenever they wanted. Which they did. They became epic and zealous through 'A Farewell To Kings' and 'Hemispheres', a surprise hit with 'Permanent Waves' and the multimillion-selling 'Moving Pictures'. They became a band apace with the times, redefining their sound (sometimes to its detriment with an album like 1982's 'Signals') and tightening their grasp on dynamics and execution through the 80s (highlighted by the excellent 'Power Windows' and 'Hold Your Fire' albums), eventually slowing down as they came into the 90s with only three studio albums proper: 'Roll The Bones', 1993's 'Counterparts' and 1996's 'Test For Echo'.

As the band grew in stature throughout the 70s, they developed a work ethic that would debilitate or splinter most other hands. In at least one interview Neil Peart refers to their time in the 70s as a "dark tunnel", wherein the band had neither the wherewithal nor the presence of mind to break the cycle they found themselves in. Though for Alex Lifeson, at least, the opportunity for development and change was an exciting one.

"I look back on the 70s as being incredibly exciting," the guitarist says. "Thankfully we were young enough to live through it. From '74 to '77 we were doing 250 shows a year and making two records. we went through one period where we were absolutely broke for eight months, didn't get paid a thing. I was living on money that me and my wife had received as wedding gifts; we had five dollars left at the end of the week for cigarettes and going out. It wasn't a problem, we went to the park with the kids more, walked places, and it taught us things that we carry even today. So in that period we learnt a lot. We were working hard, long drives, we took shifts but, fuck, we had a great time. It was so much fun.

"It just became such a natural part of our existence. I was 20 when we started our first tour, We made two records a year for those first few years, we toured constantly, came home, then back into the studio, back on the road, it just never ended. For us, getting a three-week break - 10 years after we started the band - before going in to do a record seemed like a big deal. It wasn't until 'Test For Echo' that we finally took a long break. Geddy and his wife had a baby girl and he wanted to take a year off to be with her. That was a real eye opener [laughs], taking that time off. I think 'Test...' benefited from, that, though there are still weaknesses on that record. But certainly with 'Vapor Trails' a lot had happened, we were all changed people."

"We were always insane. We spent all our time on the road, and then it'd be right into the studio, little break, back out again," says Lee later, as we stand outside the Ontario Parliament in downtown Toronto. The air has cooled, though the sky is a clear blue dome that's bright enough to cause us all to squint. Two black squirrels tussle over a bread roll on the building steps, causing a teenage girl next to us to coo delightedly. Lee and Lifeson look distractedly about them to see what the focus of her attention is. The Ontario Parliament was made famous - for Rush fans, at least - when it doubled as an art gallery on the cover of their 'Moving Pictures' album. It's odd to see the pair of them framed against its high arches as tourists wander by reading aloud from pamphlets detailing the history of the building. Randy, our driver, shrugs. "This is where all the idiots work," he sighs, indicating the grand entrance. Lee smiles and returns to his original point.

"We felt that was our job - get out there and play. That's what we were supposed to do. We didn't get a lot of airplay back then, and then we got a reputation for our live shows. And that was the way you did it - you got off your ass and got on the road. And you didn't do three shows a week, it was 17 in a row and then a day off.

"We started slowing down," says Lee as we climb back into the car pulling slowly into traffic and heading to the photography studio. Lifeson points out Rush landmarks along the way ("Maple Leaf Gardens is just there"; "We used to record a lot of our earlier stuff in a studio just down there...") as we drift through the sun-washed city.

"We were all losing touch with our families, you know," says Lee, as Lifeson pauses in his reverie. "Something had to change, and 'Grace Under Pressure' was the breaking point for me. With all the problems that were involved in making that record, and the responsibility, I became obsessed with making that record work and I ignored everybody else in my life. When it was finished, my personal life was in tatters. I didn't have any connection to my kid, to my wife or my friends. It was a bad, bad time for me, but I learnt the hard way that I was risking everything that I hold dear. That's when we decided to hold back, that we had to make an effort to be human about it all. It was a dark, dark time. I love the album, but it was a tough record to make. The producer, Steve Lillywhite, leaving us like that was horribly irresponsible, very unprofessional, and he left us in the lurch."

Lillywhite (Psychedelic Furs, Rolling Stones, U2 etc) had agreed to work with Rush on what was their first album without long-time producer Terry Brown, who had worked with the band from 1974 through until 1982. At the last moment, Lillywhite had a change of heart which left the band to fend for themselves, albeit with the help of Peter Henderson. A close friend of the band's had died. 'Afterimage' was dedicated to him, and the title (taken from Ernest Hemingway) couldn't have felt more apt.

"Lillywhite had a change of heart at the eleventh hour so we ended up working with Peter Henderson, who's a great engineer but not the producer we needed. So we ended up making a lot of decisions we didn't want to make. That was a troubled record, a cold record. Even the artwork - that figure looking out over the landscape..." says Geddy, tailing off.

"And we didn't stop working with Terry after so many years just to do it by ourselves. Which is what we ended up doing in a sense. We wanted to learn from new people, and in retrospect I learnt more through that horrible experience - talking to other producers about making records and how they made them - than I might have, but it wasn't an experience I was looking for.

"Terry Brown was our mentor in so many ways, and fantastic to work with and a dear friend and talented too, but I don't honestly think there was anything else for me to learn from him any more. And that's what it's all about. When you're working with a producer and you know what he's going to say before be comes in the room, then he doesn't have to come in the room."

We're at the photographer's studio. Geddy Lee is in sharp profile against a large dense, red backdrop, pale green granny glasses set at the end of his nose.

"That was the thing with Terry", says Lifeson, as Lee adopts a detached pose of nonchalance until the photographer harangues him into a beaming smile. "We'd made a lot of records with him and he was like the fourth member of the band, truly, but we didn't feel that we would learn my more unless we made some changes. And it was a very difficult thing to do, as we were very close as friends. Sadly, after that we kind of lost touch with each other. We see each other once every five years or whatever. It felt unpleasant letting him go; he came out on the road and we had a chat on the bus. It was a very sad affair, actually. I think he was disappointed, We loved working together, we had a wonderful time working together. A lot went on. They were, very exciting times. It was a little bit of an uncomfortable thing, now that I think about it."

WHEREAS 'GRACE...' WAS VERY NEARLY THE BREAKING point for Lee, Lifeson, who barrelled through the 70s with glee, found himself burnt out after they'd taken the 'Hold Your Fire' album around the world.

"Oh, we were so exhausted after the 'Hold Your Fire' tour, and we came off it and went straight into the studio to start work on the live album ['A Show Of Hands']. And it took forever. There was so much material to go through. By the end of it we really thought seriously about packing it in, honestly. I remember sitting in the studio here in Toronto," he waves a hand around. "When we were mixing it, and we were sitting on the back couch and we decided: 'Let's not talk about this now, this is not a good time. We're all too tired, let's take a break.' We took seven months off after that, and then there was no question of packing it in; it was not even on the agenda, just burned out I guess.

"We've lost perspective before, though not as badly as that. I remember around the time of 'Moving Pictures', and the success we were experiencing with that, and we'd go to that point where we'd hired people to do everything for you; you want a sandwich at three in the morning? You don't have to hunt it down, someone else will. And then you come home and that absolutely does not work, you know? We all had children when we were relatively young, me younger than the others, but you come home after the road and being a fancy shmancy rock star to taking the kids to school, changing a diaper, doing all the normal stuff that people do. I really try and do normal stuff as soon as I get back off the road. Geddy's the same. And I really think that helped keep us planted. I mean, it's so easy to get depressed and unhappy on the road and go over to the dark side [laughs] and get into whatever you need to get you through the day. And that sounds terrible, really, because it's not a bad lifestyle, it's a great opportunity."

In their respective downtime, both Lifeson and Lee have recorded solo records. Lifeson also produced the bands Lifer and 3 Doors Down, as well as composing the theme for the sci-fi television series Andromeda ("They gave me this napkin with what kind of character the song should have. I had no visuals, and written on it was 'Introduction of 20,000 guitars at this point'. I think I managed to give them around 19,856. That was great fun, a real challenge."). Lee's 'My Favorite Headache' came out in 2000, Lifeson's 'Victor' album in 1996. Lee's, it's fair to say (Lifeson agrees when I bring it up), was the easier listen of the two. Lifeson's cajoling, familiar, grin-fixed guitarist was gone, in his place was an album filled with vitriol and barely suppressed misogyny. It was a striking album, full of verve and attack and compounded hatred, or at least that's how it seemed.

We're back at SRO, the unsettling 'Victor' artwork lit up on a far wall. Lifeson glances at it as he talks: "I'd been home a long time then when Geddy wanted to be home (after 'Grace Under Pressure') [sic, actually it was after 'Counterparts'], and I toyed then with the idea of doing a solo record for a while. I'd never been committed enough to do it, and that was the problem I was having. I really felt that there was a point in my life where I had to start committing to things. I needed to find motivation and follow it through. So I ended up spending almost a year on that record.

"As for the anger on them, them were relationships breaking down all around me, I was having problems in my relationship. My wife and I realised that we'd started to take each other for granted; there'd been a lot of work, I'd been away a lot. It's uncommon to have stayed together as long as we have stayed together. We'd reached a crisis in our relationship and we needed to strip it down and analyse it and find where we were going. Other relationships around me were breaking down also, a lot of my friends who are the same age were really reaching a mid-life crisis. There were at least three couples that I knew at the time and the people in those were not dealing with it. The kids had grown up, they didn't feel like they had any kind of value, they had nothing to bring to the table. They didn't want to lose their identity and they thought they were being strangled by their relationship. All this stuff was happening around me, and I just thought about the darker side of relationships and love. By nature I'm very optimistic, a little romantic, a little funny maybe, but I felt really impassioned by all the stuff that was going around, and that was reflected in that album."

"Neil was very pleased that I'd managed to get word 'nihilist' in there!" says Lee when I ask him how Rush drummer and lyricist Neil Peart had reacted to the lyrics on the singer's own album. "Writing lyrics was a real discovery for me. I knew I could write okay, but I didn't know how far I could push myself. Ben Mink [who played violin on 'Losing It', on the 'Signals' album] was such an encouragement to me. He would just be: 'Well, what do you want to talk about?' And we share some of the same anger and frustrations about things in life that those conversations would turn into song. I don't think that 'Vapor Trails' might have been the album it is if I hadn't made that album.

"I didn't know or not if it was the end of Rush when I started making 'My Favorite Headache', none of us did, but I suspected that it probably was. And I was comfortable with that after a time. It was a great ride, a great time in my life, and it gave me so much in terms of making me the person I am. When I started making 'Fave' I intentionally started avoiding anything that was Rush-like, then I realised how stupid that was - it's like denying what you look like. And I never realised until recently that the last song on that album ['Grace To Grace'] almost sounds like a lead-in to 'Vapor Trails'."

IN AUGUST 1997, NEIL PEART'S DAUGHTER SELENA TAYLOR'S jeep left Highway 401 near Brighton, Ontario, resulting in a fatal crash. She was just 19. Ten months later his wife Jacqueline succumbed to cancer and also died. The band closed down and everything, understandably, went on hold. Rumours filtered through that the band had come to a halt; that they were working together again; that there would be a new album this year or the next; and then it went quiet. Lifeson did production, and made occasional appearances at his club, the Orbit Room, in Toronto. Lee followed baseball. Seasons rolled around. He met up with Ben Mink and decided to make his own record. Peart healed slowly, met someone and moved out to California, then in September 2000 he married again.

Then there were the rumours again: the band were back in the studio; they were going to make another album; they would follow up 'Test For Echo'. And then quite suddenly it seemed that they would.

"I guess five years of being out of the picture, not thinking about the band, was a very difficult time," says Lifeson. "When Neil went through his tragedy, certainly for the first year after that it was hard to focus on anything to do with music or the band. Everything just shut down on that day, actually, and once things settled down a little bit we really left it up to Neil to make the decision whether he wanted to come back. Certainly we felt the same way [that there wouldn't be another Rush album]. For the first few years Geddy and I thought that that was it. It was a very difficult recovery for Neil, it didn't really turn around until much later for him. But then when he was ready to come back to work, we sat down and we talked. And it was interesting, because we weren't really sure if any of us were ready, but we decided to go in and give it a try and see what would happen.

"The first few weeks in the studio we didn't play a single note, we talked, really. Then started to do some writing. It took a couple of months just to clear the cobwebs. Most of the stuff we originally wrote was just us going through the exercise, I think; a lot sounded dated. And then we took a break and came back, and suddenly everything was very clear to us. The machine started rolling and the record started taking a shape of its own, and we were just along for the ride after that. Everything came out so fluidly.

"With Neil, he hadn't played drums for four years apart from a two-week period when he felt the need to play, and then he played every day for those two weeks and then stopped again. So he really didn't play for four years. And Neil's the kind of guy who plays every day; I think Christmas was the only day he didn't practise. Neil's a very structured guy and very disciplined, and for him not to play for four years..." He tails off almost helplessly. "It took him a while to get his chops back, it really did."

Lee echoes his sentiments wholeheartedly. "When we were getting back together we had to go slowly in order to make Neil comfortable, and to see how the whole process was going to work out in order for Neil to come back to this city that holds a lot of memories for him and to work with us. When you see someone from your past, not only do you remember your relationship with that person, you also remember it in context of your family and your life, and it brings a whole flood of emotions back. And so it was let's just go to work every day, and let's not have a deadline, and let's see how it evolves, and pretty soon if Neil's not comfortable then we'll just call it quits or whatever. I was pretty confident that once we established the right atmosphere that slowly but surely we would start having fun again, and he was in a very positive frame of mind anyway. But it had been a long time, and the writing did not come easy. We were so used to getting things done quickly before, and in the past we were always obviously into what we were doing, but this time we had a particular determination to achieve something that had some impact on us.

"We were very secure, in a way, and very considerate of each other, very respectful, there was no pettiness this time at all. Not that there ever was a preponderance of that, but sometimes you tour, you take a break, and come back and everybody's a little bitchy in their own way. But this wasn't like that at all. There was a lot of raw emotion in the air, and there were times that it was very heartfelt what we were doing, and we were aware of the fragility of the situation and the morality, for want of a better word, of the situation.

"It wasn't just that Neil was the sole thing to get sorted out, Alex and I hadn't worked together in a long time either, but we'd both been working. Neil came back and hadn't played for four years. He couldn't play, he had no spirit. A tragedy like that just takes your spirit away, and music, especially rock music, for me, is about spirit, and more often than not a celebration of spirit. When there's no spirit, there's no music. With the sign that Neil was ready to come back, I knew that his spirit was beginning to return to him, and really this album is all about that. That's why a lot of the songs are upbeat and intense and passionate. I'm very pleased with the result. Before we figured out what the record should be there was a lot of trial and error, a lot of failed experiments."

Whether adversity or inspiration is to blame, 'Vapor Trails' is a mould-breaking Rush album. And for all its dynamism and expression it could also be their last. All good things must eventually end. And while Rush are celebrating, they're still taking tentative steps.

"I don't think about making more Rush albums, really," admits Lee. "I want to enjoy my life as much as possible. I know I can't really get on without writing, but I don't know whether it necessarily has to be with Rush any more. We did an album and it worked out, and hopefully the tour will be something we won't regret three months from now. Three hours is a lot of work, and we're six years older than we were on the last tour. I don't know how our bodies will respond to that kind of punishment; I get tired of waking up with no throat. This is the most ambitious tour we've embarked on in 15 years, and I hope that's not a mistake. Maybe it'll be the last big tour we do. Don't get me wrong, this album is, in some ways, the most successful journey that the three of us have been on together, so it's very possible that we'll repeat that experience, but I don't want to take anything for granted any more. After all that's happened, how can we?"

Above Toronto the sun is shining, and for a moment it feels like it's shining just on us...

Soothing Vapors

Is 'Vapor Trails' the new '2112'? (I thought that was the Queen musical-Ed.)

As Geddy Lee so rightly points out, 'Vapor Trails' is one of the most successful musical journeys that Rush has made. No strangers to adversity, it's no surprise that the circumstances surrounding the new album and its vibrant results should remind Lee of the young Rush struggling for commercial and artistic acceptance when they were making '2112'.

Lifeson calls '2112' their turning point, 'Vapor Trails' their rebirth. And the immediacy and energy that permeates both is evident throughout. After the crises of 'Caress Of Steel', the band were being harangued by label and management to define their direction and hopefully repeat the award-winning success of 'Fly By Night'. They united in produce a concept album that defied every expectation. Their bravura paid off, ultimately allowing them to become the band they wanted to be.

"I really liken 'Vapor...' to '2112'," says Lee, "because that was also an album of great intensity and passion. We felt very united making '2112'. There was a conscious effort to do something and do it with all our heart, and the same atmosphere was present in some ways when we did 'Vapour...' I don't know why, it just reminds me of '2112', it feels like '2112' 21 years later, or whatever it is. Them's something quite passionate about 'Vapor...', there really is. It's one thing to say, but those emotions were present and at work throughout the recording sessions.

"Of course, we wrote almost all of '2112' on acoustic guitar, and it's such a heavy record," he says, pausing to chuckle, "but you sit down with a nylon-string acoustic and you're giving it some stick and it's got great bottom end, and it's not that big a a stretch in your mind translating it into a nice, big Marshall sound. It's funny, when you look at some of those things they seem so very naïve, but at the time its an honest reflection of the way we thought at the time. And this time we just did things our own way again, just the three of us with that same intensity. I think that's why we produced ourselves, as well.

"And once we got into it I realised that we should be able to push each other And I think that in the break through the difficulties of the last number of years, we became so close as friends that that was never going to go away."

"I can honestly say that our relationship and friendship is deeper and closer now than it's ever been, very much like how we felt during '2112'." Says Lifeson. "A lot of it had to do with this record, a lot of it had to do with what happened to Neil. It really bonded us, it brought us closer together. But we've always been close as a band, we've always laughed together, always been there for each, other and that's always made everything a lot easier."