Neil Peart's Road To Recovery

[An Excerpt from Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road]

Toronto Star, July 27, 2002, transcribed by pwrwindows

Devastated by the loss of his wife and daughter, Rush's drummer headed out on his motorbike on a long and winding route around the continent to find himself again

After this spring's release of Rush's 17th studio album, Vapor Trails, drummer/lyricist Neil Peart hit the road with singer/bassist Geddy Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson for the first time since his "waking nightmare" began. In 1997, Peart's teenage daughter died in a car accident and, less than a year later, his wife died of cancer. With nothing left to lose, he set out on his motorcycle, travelling 89,000 kilometres in 14 months from Quebec to Alaska, down to Mexico and Belize and back to Quebec, with many stops in between. Peart documented his journey in the recently released Ghost Rider: Travels On The Healing Road (ECW Press). As an exclusive to The Star, here are excerpts from three chapters.

CHAPTER 1: INTO EXILE

Outside the house by the lake the heavy rain seemed to hold down the darkness, grudging the slow fade from black, to blue, to gray. As I prepared that last breakfast at home, squeezing the oranges, boiling the eggs, smelling the toast and coffee, I looked out the kitchen window at the dim Quebec woods gradually coming into focus. Near the end of a wet summer, the spruce, birch, poplars, and cedars were densely green, glossy and dripping.

For this momentous departure I had hoped for a better omen than this cold, dark, rainy morning, but it did have a certain pathetic fallacy, a sympathy with my interior weather. In any case, the weather didn't matter; I was going. I still didn't know where (Alaska? Mexico? Patagonia?), or for how long (two months? four months? a year?), but I knew I had to go. My life depended on it.

Sipping the last cup of coffee, I wrestled into my leathers, pulled on my boots, then rinsed the cup in the sink and picked up the red helmet. I pushed it down over the thin balaclava, tightened the plastic rainsuit around my neck, and pulled on my thick waterproof gloves. I knew this was going to be a cold, wet ride, and if my brain wasn't ready for it, at least my body would be prepared. That much I could manage.

The house on the lake had been my sanctuary, the only place I still loved, the only thing I had left, and I was tearing myself away from it unwillingly, but desperately. I didn't expect to be back for a while, and one dark corner of my mind feared that I might never get back home again. This would be a perilous journey, and it might end badly. By this point in my life I knew that bad things could happen, even to me.

I had no definite plans, just a vague notion to head north along the Ottawa River, then turn west, maybe across Canada to Vancouver to visit my brother Danny and his family. Or, I might head northwest through the Yukon and Northwest Territories to Alaska, where I had never travelled, then catch the ferry down the coast of British Columbia toward Vancouver. Knowing that ferry would be booked up long in advance, it was the one reservation I had dared to make, and as I prepared to set out on that dark, rainy morning of Aug. 20, 1998, I had two and a half weeks to get to Haines, Alaska - all the while knowing that it didn't really matter, to me or anyone else, if I kept that reservation.

Out in the driveway, the red motorcycle sat on its centrestand, beaded with raindrops and gleaming from my careful preparation. The motor was warming on fast idle, a plume of white vapor jetting out behind, its steady hum muffled by my earplugs and helmet. ...

My well-travelled BMW R1100GS (the "adventure-touring" model) was packed with everything I might need for a trip of unknown duration, to unknown destinations. Two hard-shell luggage cases flanked the rear wheel, while behind the saddle I had stacked a duffel bag, tent, sleeping bag, inflatable foam pad, groundsheet, tool kit, and a small red plastic gas can. I wanted to be prepared for anything, anywhere. ...

Just over a year before that morning, on the night of Aug. 10, 1997, a police car had driven down that same driveway to bring us news of the first tragedy. That morning my wife Jackie and I had kissed and hugged our 19-year-old daughter, Selena, as she set out to drive back to Toronto, ready to start university that September. As night came on, the hour passed when we should have heard from her, and Jackie became increasingly worried. An incorrigible optimist (back then, at least), I still didn't believe in the possibility of anything bad happening to Selena, or to any of us, and I was sure it was just teenage thoughtlessness. She would call; there'd be some excuse.

When I saw headlights coming down the driveway to where the house lights showed the markings of a police car, I remembered the previous summer when the provincial police came to ask about a robbery down the road, and I thought it must be something like that. A mother has a certain built-in radar detector, however, and the moment I announced that it was the police, I saw Jackie's eyes go wide and her face turn white; she knew.

Instinctively, I took her hand as we went out to the driveway to face the local police chief, Ernie Woods. He led us inside and showed us the fax he had received from the Ontario Provincial Police, and we tried to take in his words: "bad news," "maybe you'd better sit down." Then we tried to read the black lines on the paper, tried to make sense of the incomprehensible, to believe the unacceptable. My mind was reeling in a hopeless struggle to absorb those words. "Single car accident," "apparently lost control," "dead at the scene."

"No," Jackie breathed, then louder, "NO," again and again, as she collapsed to the floor in the front hall. At first I just stood there, paralyzed with horror and shock, and it was only when I saw Jackie start to get up that I felt afraid of what she might do, and I fell down beside her and held her. She struggled against me and told me to let her go, but I wouldn't. ...

I held onto Jackie until she was overcome by the numbing protection of shock, and asked Chief Ernie to call our local doctor. ... Dr. Spunt came and tried to say comforting things, but we were unreceptive. Sometime later, Chief Ernie left, then Dr. Spunt too, and for the rest of the night I walked endlessly around the living-room carpet (what I learned later is called the "search mode," in which I was unconsciously "trying to find the lost one," just as some animals and birds do), while Jackie sat and stared into space, neither of us saying anything. ...

It soon became apparent that Jackie's world was completely shattered forever; she had fallen to pieces, and she never came back together again.

And neither did the two of us, really, though I tried to do everything I could for her. As my life suddenly forced me to learn more than anyone ever wanted to know about grief and bereavement, I learned the sad fact that most couples do not stay together after losing a child. Outrageous! So wrong, so unfair, so cruel, to heap more pain and injustice on those who had suffered so much already. In my blissful ignorance, I would have imagined the opposite - that those who most shared the loss would cling to each other. But no.

Maybe it's because the mutually bereaved represent a constant reminder to each other, almost a reproach, or it might run as deep as the "selfish genes" rejecting an unsuccessful effort at reproduction. Whatever it was, it was harsh to think that Jackie and I had survived 22 years of common-law marriage; had managed to stay together through bad times and good (with only a couple of "temporary estrangements"); through poverty and wealth, failure and success, crises of youth and midlife and middle age (she was 42; I was 45); through all the stages of Selena's childhood and adolescence; and even my frequent absences, both as a touring musician and an inveterate traveller. We had made it through all that, and now the loss of what we each treasured most would drive us apart. ...

She wouldn't let me comfort her, and didn't want anything to do with me really. It was as though she knew she needed me, but her tortured heart had no place in it for me, or anybody. If she couldn't have Selena, she no longer wanted anything - she just wanted to die. She had to be coaxed into eating anything at all, and talked of suicide constantly. I had to keep a close watch on her sedatives and sleeping pills, and make sure she was never left alone. When she did surrender to a drugged sleep, she held a framed picture of Selena in her arms.

After a couple of weeks I took Jackie away to London, England ... and eventually we moved into a small flat near Hyde Park, where we stayed for six months. We started seeing a grief counsellor, "Dr. Deborah," several times a week at the Traumatic Stress Clinic, which seemed to help a little, and at least got us outside occasionally. It was hard for me to try to force Jackie even to take a walk, for she was tortured by everything she saw - by advertisements for back-to-school clothes (Selena!), children playing in the park (Selena!), young girls on horseback taking riding lessons (Selena!), pretty young women in the full pride of youth (Selena!). These same triggers stabbed me too, of course, and I also felt bleak and morose and often tearful, but it seemed I was already building a wall against things which were too painful for me to deal with, wearing mental blinkers when I was outside in the busy streets of London. I would just flinch and turn away from such associations, but Jackie remained raw and vulnerable, unable to protect herself from the horror of memory. ...

The following January, when we were finally thinking about returning from London to try to find some kind of life back in Canada, Jackie began to suffer from severe back pain and nocturnal coughing. She refused to let me get a doctor, saying, "They'll just say it's stress," but Dr. Deborah finally prevailed on me to make an executive decision and get a doctor anyway. On the eve of our departure, Jackie was diagnosed with terminal cancer (the doctors called it cancer, but of course it was a broken heart), and a second nightmare began.

Jackie's brother Steven met us in Toronto and soon took over the household ... supervising Jackie's care as I felt myself slipping into a kind of "protective insanity," a numb refuge of alcohol and drugs.

Jackie, however, received the news almost gratefully - as though this was the only acceptable fate for her, the only price she could pay. After months of misery, despair, and anger (often directed at me, as the handiest "object"), she never uttered a harsh word after that diagnosis, and rarely even cried. To her, the illness was a terrible kind of justice. To me, however, it was simply terrible. And unbearable.

After two months of dissipation in Toronto, I pulled myself together, and we fulfilled Jackie's wish to go to Barbados. Two years previously we had enjoyed a memorable family vacation in that pleasant island-nation, and it offered sufficient medical services to allow us to continue providing home care for Jackie, even when she began to decline sharply, needing oxygen most of the time, slipping away both mentally and physically, until a series of strokes brought a relatively merciful end.

Exhausted and desolated, I flew back to Toronto, staying there just long enough to organize the house and put it on the market, with more help from family and friends, then got away to the house on the lake, still not knowing what I was going to do. Before she died, Jackie had given me a clue, saying, "Oh, you'll just go travelling on your motorcycle," but at that time I couldn't even imagine doing that. But as the long, empty days and nights of that dark summer slowly passed, it began to seem like the only thing to do. ...

I remember thinking, "How does anyone survive something like this? And if they do, what kind of person comes out the other end?" I didn't know, but throughout that dark time of grief, sorrow, desolation, and complete despair, something in me seemed determined to carry on. Something would come up. ...

In any case, I was now setting out on my motorcycle to try to figure out what kind of person I was going to be, and what kind of world I was going to live in.

CHAPTER 4: WEST TO ALASKA

The little port of Haines would prove to be my definitive Alaskan experience. I stopped at a small liquor store to look for a bottle of single-malt whisky, and I overheard a fisherman telling the owner about the 49-pound halibut he'd just caught. On his way out the door he pointed down toward Main St., a few blocks away, where a black bear was loping across the road.

With a few hours to kill until the ferry sailed, I went to the Lighthouse Restaurant and caught my own halibut - from the menu. A few other travellers seemed to be biding their time there too, mostly older retired couples, and they soon began talking among themselves from table to table, comfortable among strangers so like themselves, from the same generation of friendly, open Americans. I overheard one of the men trying to remember the name of a small town away up north in the Northwest Territories, right on the Arctic Ocean, and I offered, "Tuktoyaktuk?" and soon everyone was exchanging travellers' tales. ...

After dinner, I took a slow ride around the inlet, and at the top, where the Chilkoot River flowed in, I saw a few people standing on a small bridge. I slowed to see what they were looking at, then stopped and switched off the engine.

Straddling the bike, I watched five grizzly bears at the river's edge: a sow with three cubs, and one half-grown - not as big as they get, but big. A young Australian passed me his binoculars, and I got a close-up view of them feeding on the dead salmon. ...

At the ferry dock I pulled the bike onto the centrestand in the line of waiting vehicles, took out Jack London's The Sea Wolf, and relaxed in the saddle. ... Rain began to fall with growing intensity, so I took shelter under the terminal overhang for awhile, or walked around in my rainsuit.

I passed a young woman out walking her little dog, and she looked pretty under the lights of the rain-washed parking lot. She gave me a smile that seemed to go right through me, the way that girls can sometimes do, and I felt suddenly galvanized - dumb, nervous, and afraid. Pretty girls have always tended to have that effect on me, on the rare occasions when I was confronted by one, but I hadn't felt any of those kinds of feelings for a long time.

Perhaps in line with an earlier soliloquy about "unimagined affection," I had never felt I was particularly attractive to women, but something seemed different now. Later, when I was around friends, they would confirm that I seemed suddenly to attract a certain attentiveness from women. Even though I still wore my wedding ring (as Jackie and I both had, despite being unsanctioned by church and state), and sure wasn't sending out any conscious "signals," waitresses rested their fingers lightly on my arm, cashiers gave me sympathetic smiles, women on the street sometimes poured their eyes into mine. Taking the Romantic View, I liked to imagine their feminine radar could detect the Air of Tragedy which must surely surround me like an aura. Maybe it was just the more prosaic Air of Availability. Or the line that Tom Robbins translates from Baudelaire as, "Women love these fierce invalids home from hot climates."

This pretty girl on the ferry dock in Haines, Alaska, looked to be travelling alone with her little dog, and if she was sending me some kind of signal, what should I do? Was this one of those "opportunities" I should think about, or just an overactive imagination? Whatever it was, I was not ready to deal with it, and when I didn't encounter her again aboard the ship, I put the question out of my mind.

CHAPTER 6: THE LONELIEST ROAD IN AMERICA

From Waterton Lakes National Park, I was planning to visit Glacier National Park, just over the border in Montana (the other part of what was touted as the "Waterton Glacier International Peace Park"). But as I looked over the map I noticed that Fernie, B.C., where my friend and fellow "Rushian," Alex, was born, was just to the west. Wouldn't it be fun to send him a postcard from there? It was only about 500 miles out of my way (a mere scenic diversion), and offered a southerly route back into the Rockies I'd never travelled before, over the Crowsnest Pass. From there, I could follow the meanderings of Highway 3 to the euphoniously named Yahk, cross the border into Idaho, and make my way east again to Glacier. ...

Like Nelson, Fernie was a small mountain community built partly on hard labour (mining and logging) and partly on outdoor recreation, for it was surrounded by mountains and lakes that offered both winter and summer activities. As I cruised the half-quaint, half-prosaic main street (the practicalities of hardware and work clothes, the play-toys of snowboards and bicycles), I decided the best place to find a postcard which said "Fernie" on it would be the drug store. Sure enough, a few minutes later I was sitting on my motorcycle, parked on its centrestand, writing a postcard to Alex.

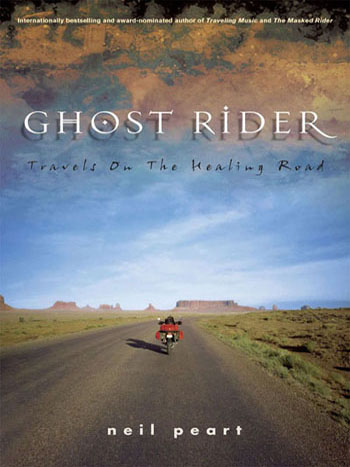

Concerned only that the name "Fernie" appear on the card, I hadn't really paid attention to the picture, but before I started writing I noticed the caption at the top: "Ghost Rider." Turning it over, I saw a photograph of a lenticular cloud trailing off the peak of Trinity Mountain. Ghost Rider was apparently the local name for this atmospheric phenomenon.

Now, it must be explained that Alex and I shared a particular mode of writing to each other in "Moronese," and with the pen in my left (wrong) hand I started scrawling, "Eye em thuh gost rydur." Then I stopped, my head jerked back, and I thought, "Whoa, yeah! - I am the ghost rider!" The phantoms I carried with me, the way the world and other people's lives seemed insubstantial and unreal, and the way I myself felt alienated, disintegrated, and unengaged with life around me. "Oh yes," I thought, "that's me all right. I am the ghost rider."