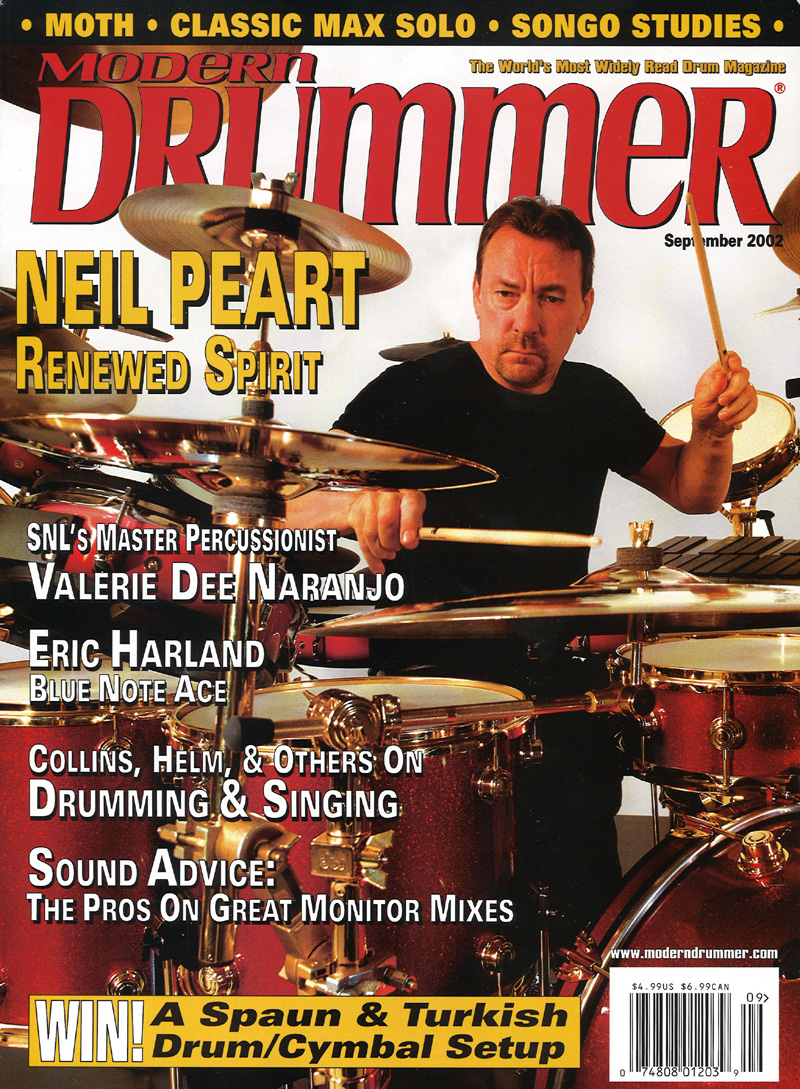

Neil Peart: The Fire Returns

By William F. Miller, Modern Drummer, September 2002, transcribed by John Patuto

When you're one of the most scrutinized and obsessed-over musicians of your generation, a five-year absence from the scene is profound. Now, with the release of Vapor Trails, Neil Peart and Rush return, bringing with them the scars of tragedy, and the wonder of rebirth.

The Fire Returns

Neil Peart has lived a life of extremes. He's taken a God-given talent, and through intense focus and total commitment, achieved great things in drumming. No one save Buddy Rich has inspired more drummers the world over than Neil Peart. In his nearly thirty-year career with Rush - including twenty-one gold-or-better albums totaling more than thirty-five million copies sold - he's accomplished more in music than most people could ever dream of.

Just what is it about Peart that allowed him to accomplish so much? Ask anyone who has spent time with the man. They'll all give you the same answer. Neil has a deep passion, a fire, for what he does. (It's been a favorite topic in his lyric writing.) No great artist achieves without it.

That passion was all but snuffed out five years ago, when Peart's family was rocked by tragedy. In August of 1997, Neil's nineteen -year-old daughter, Selena, was killed in an automobile accident. And then, unbelievably, within a year, his wife Jackie succumbed to cancer. The magnitude of the loss was unthinkable ... unimaginable.

How does one go on after experiencing that kind of loss? As brilliant a man as he is, Neil didn't have the answer. So he literally went searching for a reason to live. Peart spent the next couple of years on a solitary journey, motorcycling thousands of miles across North and Central America. It was a much-needed escape, because even thinking about anything relating to his previous life brought him nothing but pain.

Peart eventually came back to his home in Canada. He found his drums waiting there, and over the course of a two-week playing jag he reintroduced himself to the joy, excitement, and, yes, frustration of drumming. A little spark was lit ... possibly a small chance at life ... a reason to go on. But Neil admits that he knew he wasn't ready to step back into the limelight or make the kind of commitment necessary to re-join Rush. It would take another couple of years - and lots of help, love, and support from family and friends - before he would be ready to try.

In January of 2001, Neil Peart, Geddy Lee, and Alex Lifeson finally came together to see if they could reassemble what had once been a great band. According to Neil, "We laid out no parameters, no goals, no limitations, only that we would take a relaxed, civilized approach to the project." The trio worked diligently, methodically writing and recording new material. After a year of starts and stops and hits and misses, the trio emerged with seventy four minutes of music, making up the material found on their latest offering, Vapor Trails.

Surprisingly, Rush 2002 is more aggressive than ever. The guitar solos and keyboards have been replaced by bombast and sheets of sonic intensity. There's also a stronger sense of groove in Peart's playing, something that wasn't as prevalent in the past. Neil says of the new direction, "We envisioned advertising slogans along the lines of. 'If you hated them before, you'll really hate them now!'" Reviews may be mixed about the material, but the drumming is strong. In fact, the first cut, "One Little Victory," opens with a slamming double-pedal foray that clearly announces to the world, "He's baaaack!"

Peart's drumming prowess has returned, no question about it. At a recent practice session for the fifty-plus-date Rush tour, Neil was incredibly strong. Watching him play at the band's rehearsal space-unamplified-from twenty paces was nothing short of astonishing. No one plays with more power than Neil Peart. His style is perfectly suited for stadium performance. But as you'd expect, also within that power is an intellect and wit that enjoys contorting patterns and syncopating fills. And added to that is Neil's new appreciation for the groove. It looks like Peart may be gearing up to inspire a whole new generation of drummers - yet again.

Off the drums, Neil has changed. How could such tragic events not affect him? He recently remarried and is doing his best to build a new life. In my many get-togethers with him in the past, there was never any sense of weakness or vulnerability. The old Neil was driven, self-assured, strong, brilliant, and at times a tad aloof. He's different now. Brilliant? No doubt. Confident and strong? Perhaps. Aloof? No way. There's a greater sensitivity in him today, a look of compassion behind the eyes. Neil Peart has emerged from tragedy an even greater human being.

I just want to start off by saying thanks for granting us the interview. I know this is tough for you.

I haven't done one of these in a long time. I don't know how good it will be.

Let's start with something easy. Your drumming sounds good on Vapor Trails. In fact, it's one of your most grooving performances.

Well, that's a wonderful comment. I'm sure glad to hear it, because I was trying my best to achieve that. The whole way we went about making this record was so different from any we've done in the past that it might have permitted a more grooving approach to come through.

A lot of the songs were just jams, where Geddy and Alex got together in front of a recorder, set up a groove on a rhythm machine, and started playing. And then later, Geddy would go back and sift through those jams and say, "This eight bars is good," "This four bars is good," or, "If we took that two bars and repeated it, that would be good." So they stitched together these things into a structure.

At the same time, I was feeding Geddy lyrics so he could sing over the ideas they were coming up with. And then we did what we call "leap-frogging," where we individually work on the songs ourselves, the drum parts, guitar parts, and vocal/bass parts-without holding up each other and without getting caught up in too much editorial commentary from each other.

Can you elaborate on the idea of leap-frogging?

We start off with that rough tape Geddy will have created, and then Alex will add guitar parts more to the vision he has for the song. Then I'll take that tape and come up with drum parts that I think will work. Then Geddy will respond to my drum parts and say, "Well, the bass part would be better if it went like this." Then I'll hear that and it'll give me ideas. So we're constantly improvising and developing the ideas, even though we're never really playing the song together.

It sounds as if you don't like each other.

[laughs] That's not the case at all. We've played together for twenty-seven years. I was actually thinking today about how many times we've played together. It's something like tens of thousands of times. We really know each other well as players and as people. So it isn't necessary for us to sit in a room and hash it out all at the same time.

Our current thinking goes on to that work tape . My current thinking on the drum part goes on there, and then it's talked about, of course, in between each of those takes: "Well, I like what you're doing, but it might be cool if you did this."

A good example of this process is "One Little Victory." I'd been working on that tune and came up with that double bass part. I thought it worked perfectly for the end of the song. But Geddy said, "That's a great part. You ought to open the song with it. That would just kill." Frankly, I wouldn't have done it that way-I don't think I would have been so assertive-but Geddy suggested it and I said, "Okay, I'll try it."

One thing I'm not clear about is, how did this method of developing parts help you to create a more grooving performance?

For this record we moved straight into the recording studio, where in the past we'd always go through that process of refinement-arranging the song, working on our parts, and then all being satisfied with them-before we'd go into the studio. I could then go in and record all of the drum parts in two days. I would be focused on producing that performance, the one that we had come up with during our refining process.

That method has good qualities, in that it would sometimes drive me to a level that I hadn't reached before, just putting that pressure on me to push a little further. So I like that in a way. But for Vapor Trails we decided to stay in the same studio where we were doing the writing and pre-production and just gradually start recording songs that we thought were ready. It was a much more gradual process.

If I went in to work on a drum part, I could just play around with it and not be so stressed about it. There was never any pressure that it had to be the final take. A lot of the drum tracks were spontaneous in the sense that things had never been played that way before. It was an easier way to work.

I can see how that attitude would help you groove. But you also mentioned earlier that the feel was something you were very concerned about.

The pulse was a big factor in my thinking. In the past, I would focus on the technical parts. That was the challenge, pulling off some little bit that I liked. That's what I was listening for. This time I was thinking about smoothing out my parts, making them less jarring for the listener.

So would you say this is one way you've grown musically during the long break away from the band?

I suppose so. Not only should your approach to the instrument grow with time, but so should your understanding of what you're trying to achieve. I found that for this record I was thinking on different levels, trying to satisfy what I wanted to hear in any given song. My critical faculties have refined and developed to where I'm listening for a whole musical effect to come out of the technique, not the technique itself.

Besides the focus on the groove, the other thing that jumps out about Vapor Trails is the aggressive nature of the material and the production. This is one of the heaviest records you guys have ever done.

Yeah, it is, and that's another thing that grew organically. A distinct thing about the way the three of us work together is that we never sit down on day one and layout a format and say, "Okay, here's what we want to do. We want to shape it like this. I want this kind of feel. And I want a certain number of songs with these themes."

I assumed you did that.

No, not at all. To the total contrary, we let things grow. We took our time. It had been five years since we worked together on a creative level, so we deliberately made it gradual and relaxed. We paced it in a way that would be organic. We didn't set any deadlines. We didn't say, "By four weeks we want all the songs to be written, and three weeks later we'll be ready for demos." We didn't lay it out that way at all. We just started working: "Let's see what happens."

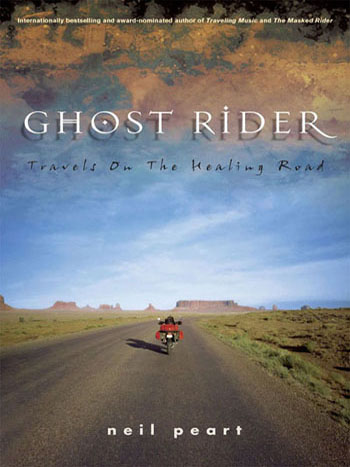

I described the way that Geddy and Alex worked together just playing, basically stitching ideas together. But that was a process that took weeks. I was working on lyrics at the same time, but there were no songs coming out. So I was on hold at that point. I actually started writing a book to fill the time, which is called Ghost Rider, about my motorcycling travels over the past few years. But I was in kind of a waiting mode.

I guess at that point you weren't drumming a lot. What was going on with your playing?

Actually, besides writing, I was practicing every day. I was playing all of the time, which was great because it helped me fine-tune my skills. I'd go in there every day ...and work on something and record it myself as a demo for my own reference.

The three of you were all in the same location?

Right. We stayed in a small studio here in Toronto, with me at one end of the building writing lyrics and playing drums and Geddy and Alex at the other end working on ideas. We actually refined the studio, because we didn't want to be forced into another facility to make the record. We completely changed the room to make it sound good for drums. And we did it inexpensively. We put up sheets of wallboard where required and livened the room.We didn't feel any pressure regarding how much time we were taking, partly because we weren't working in some expensive studio environment. It was our space, our own little music factory that we would go to every day to do our work.

In that setting, I would think it might be hard to know when a record was finished. You could just keep working on parts ....

We didn't even add up the number of songs, to give you an example of how casual we were about it. We just kept writing. We didn't time them out to see if we had enough for a finished CD. Once we had ten songs we started to think, "Well, maybe that's enough." But then Geddy and Alex said, "No, we're not done writing yet." They felt they needed more pieces of music to completely contain all they wanted to express.

I think that Geddy and Alex had certain inner musical agendas of their own for what they wanted to accomplish. For instance, I know that Alex was determined not to have any keyboards on the record. He wanted to cover that role texturally and harmonically on the guitar.

Did you have an individual agenda? The reason I ask is, there's a certain amount of swagger coming from the drum chair. It wasn't just volume ....

No, I understand. I think I know what you're getting at, and it intrigues me. I think what was going on in the drum parts was an adrenaline factor, which really pumped up the performance. While I'd like to think I was playing with a bit of swagger, as you say, I think it was more a case of my being very excited about the material and about being back together making music I love with my friends.

You can hear that in the music.

Yeah, I think there's also a new level of freshness for me, coming back to the instrument with a new sense of rededication. During my time away I really was repelled by anything that was so central to my life, like drumming and music. I didn't play for two years. I didn't touch a drumstick for two years. Everything that had been the center of my life before was obviously not good for me emotionally, so I wanted nothing to do with it.

When I did come back and play, it was when I was at the very lowest point. I was so desperate. It was like, What can I do now? But the answer came to me: I'll play the drums.

I rented a little rehearsal studio, took a drumset in there, and played every day. I started surrendering to drumming and exploring it in an organic way. At a certain point I realized I was telling my story on the drums. I was playing through every emotion the past two years had put me through. There were the angry parts, the sorrowful parts, the traveling parts: "Okay, this is me on the road," "This is me really mad." The drums were helping me express my feelings, my story. It showed me that the drums were still an instrument I could communicate through and that I could surrender to.

That all happened during a two-week period, where I poured myself into the drums and nourished myself with them. And then I realized, Okay, I'm ready to play, but I'm not ready to work. I knew I couldn't face the pressure of collaboration and the ambition of creating and being responsible to other people. I knew I didn't have the strength for any of that. But I knew I could play if I wanted to, that I could tell my story, and that I had something to communicate. That was a really important turning point for me. And even though it was almost another two years before that bore fruit, it still took seed in my mind as something to hold on to.

Was there ever a point during those bleak years where you felt like you just wouldn't come back to music and drumming at all?

There was a period of time when I was certain that I would never play drums or write lyrics or a book again. Because who cares? What does it matter? It didn't matter. Nothing mattered very much.

The only thing I was motivated to do was travel, to just go down the road every day to see what was over the next hill or around the next comer. Hope was the only muscle at work then, the hope that maybe something would come up. I kept saying to myself, Something will come up, something will come up. It's probably the only thing that kept me alive.

I was fortunate at the time to be able to retire from the world like that and to have the time to build a life again. Everything had been so destroyed and ripped out from under me that I didn't have a world to have faith in anymore. But after a lot of time, life became beautiful and precious again.

Sorry. I didn't think I would get into these things.

And you didn't think this was going to be a good interview.

[smiles] Let's get back to drumming.

Okay. Listening to Vapor Trails, there are moments where it seems you're doing a good Keith Moon impersonation.

Great! I'm glad you picked up on that. In fact, I was thinking about Keith quite a bit. Interesting story: During the time I was rediscovering music, I was moving house and digging out old boxes of records, things I hadn't listened to in a long time. I didn't want to hear more recent music, because it made me think about things. But the older stuff from my youth brought some measure of happiness.

I went back and listened to some of the best of Keith Moon's playing. In listening to him on the Tommy album, well, I was full of admiration. Keith's playing on that record is sublime. The same with Who's Next. But Tommy, to me, is such a masterpiece of drumming. It shows how smooth and flowing Keith's insanity could be.

Around that same time, I read that biography of him, Moon: The Life And Death Of A Rock Legend. It's very well done. So I was thinking a lot about Keith, and looking at his life. And again, he was the total hero of my teenage years . But in the actual dynamic of his life, he was pretty much washed up as a drummer before he was thirty because of his insanities and his indulgences. He died at the age of thirty-two, leaving behind a wife and daughter. I couldn't help but be struck by that.

But anyway, re-examining how great Keith was at that time revitalized that part of my drumming. And yes, there were certain parts on this record where I thought, Let's do it the Keith Moon way.

In the past, you always seemed to draw inspiration from music and drummers playing in the current scene. Were there any modern influences in your playing?

Hmmm. It's strange with modern music right now. As always, I find myself enjoying it. I listen to modern rock radio and like it, but it's not very much drummers' music right now. I love what's developed between rock and rap, like that Linkin Park song "In The End." I think that's a masterpiece of combining influences.

I enjoy the music, but I'm not hearing a lot of interesting drumming lately. Limp Bizkit and those types of bands are not really drummers' music from a player's point of view. Maybe I'm wrong and maybe there are other examples that I'm not familiar with, but when I hear that music that's the one thing that occurs to me. I can't imagine it's very exciting to be a drummer in a band like that.

Because it's more focused on laying down the time?

Yeah. There doesn't seem to be a lot of space for interesting things drum-wise. I mean, many of those drummers sound like good players. But the rhythms tend to be beat-oriented. It reminds me of something Tony Williams said about rock drumming: Rock drummers don't play drums, they play beats. I think that may be true now more than ever.

There is a sense that, because of things like digital editing, drummers' parts are being heavily "adjusted" and processed.

Why is that happening? Shouldn't it be the drummer's decision? For instance, in the making of this record, we used editing to capture spontaneity. If there was a time when I was whipping out on a part or playing one of those crazy Keith Moon-inspired fills and only did it a certain way once, then we used that part. But there was no manipulation going on of moving beats or things like that to make me sound better.

Technology can be our friend in terms of allowing spontaneity and encouraging freshness and capturing it. But I would never be satisfied with having somebody take my drum part and correct it. I would do that myself with sweat and blisters. That's the nature of what you're supposed to do with practice: "Okay, I'll do it again and do it better." That would be my choice.

Speaking of practice, you were away from drumming for such a long time. Was it tough to build back your ability?

I was thinking that it would be tough to "rebuild" my playing, but everything came back so readily and so naturally. Everything that I could play before I could play again. Of course, some transitions were rusty- getting one arm over the other, for instance. Physical dexterity like that took a couple of days to smooth out. But as far as actual playing, I think the muscle memory must be so deep after all the years I'd been playing-thirty-five years at that time. I've played a lot of drums in thirty-five years. It wasn't going to go away.

At times you play so hard and in such a physical way. Did you have to build up your endurance and strength?

I kept up the stamina through other things. I did a lot of cross-country skiing and a lot of hiking. I stayed physically active. I've never turned into a slug, physically, so that wasn't a problem. The process of getting the calluses back on the hands was the only thing necessary to rebuild.

After such a long break, I was wondering if, when you returned to the kit, did it feel comfortable? Or did you need to reposition things?

I didn't change a thing. In fact I'm using the same DW kit I used on the last record and tour. The biggest change I went through occurred years ago, when I first started studying with Freddie Gruber. I completely changed my setup at that time to be more natural and more ergonomic.

The only thing I did experiment with this time while we were recording was my snare drum selection. I ended up using a combination of DW and Yamaha snare drums. I've always liked the DWs. And the people at Yamaha were very nice and gave me two very special drums that I used quite a bit on the record. One had a bamboo shell that was very bright-sounding. It worked well on the record.

What about things like cymbals? Most drummers like to experiment with new models.

Yeah, but the classic Zildjians are simply the sound that I want to hear out of a cymbal. It's a very musical, controlled swell. There are other cymbal sounds I like and that I like to hear other people play. But for my voice, it's the Zildjians. I've been playing them for years.

You're in the process of preparing for a long tour. And one of the highlights of a Rush concert is your extended drum solo, which is somewhat composed. What are you doing to prepare for it?

It's a good time to discuss this because I'm working on the solo now. I'm still trying to decide on an approach. I can look at the solo that evolved up to the last tour, which was a complete piece of music that expressed my influences, background, and explorations. It's my past and present all contained within one solo. I could easily go back to something similar to it.

Another part of my mind, though, is saying to not do anything like the previous solos. I'm thinking of other ways that I might approach it. Of course, I feel that I want to have some of the sections that I've used over the years. They've survived a long time because they're autobiographical or close to me. They help me get across what I want to express musically in a solo in terms of presenting a complete array of things that a drum solo can be in terms of rhythm, dynamics, and expression.

When most drummers take a break from playing, they come back to the kit with a fresh approach. Coming back to the drums after such a long break, did you find that you had a lot of new ideas?

Yes, I found myself going places that I hadn't been before. Some are tiny little baby things that I almost hesitate to recount because the principle is more important, the movement as a whole is more important.

What would be a small example?

One would be in the song "Ghost Rider." I was looking for a subtle fill to lead into a verse. I ended up playing hits on a few cymbals. I'd never done anything like that before. It's nothing technically, but I was very happy with the effect. I didn't want to do a drum fill, and I didn't want to just come in with time on the downbeat, so I tried that and it worked.

When I hear things like that I secretly smile to myself, because it's something I don't think will impress a listener or another drummer, but it just pleases me to have gone somewhere different and accomplished something musically in a fresh way.

It's great to hear you be so excited about drumming again . You seem very committed to the music.

Commitment is the word. I have a commitment to the music, and to Geddy and Alex. They've been such supportive friends to me through all of this. No one could have been more sympathetic, compassionate, and understanding. When we came back together to work it was because I had a commitment to them.

You're turning fifty this coming September 12. What are your thoughts now that you're at the half-century mark concerning life, music, and drumming?

I guess my understanding of life has unwillingly been enlarged to a great degree, in that I've been to the blackest place that life can take you. With the support of friends and family, I've fortunately led myself through a lot of that dark time. I never knew how important people could be until I really needed them.

The age thing honestly doesn't figure in my thinking. I've read that everyone has an inner age that they think they are, regardless of their actual age. I really think of myself as being about thirty. In modem life it's a matter of keeping your prime going as long as you can.

Let's take that metaphor into the world of drumming. You go through the time of learning and experimenting, and you develop your voice as a musician. As long as you can sustain that prime of your life musically, mentally, emotionally, and physically, then that's your time.

Hearing you talk about all of this, it really seems as if you still have the fire.

Well, I lost it for a while. But I have it back.

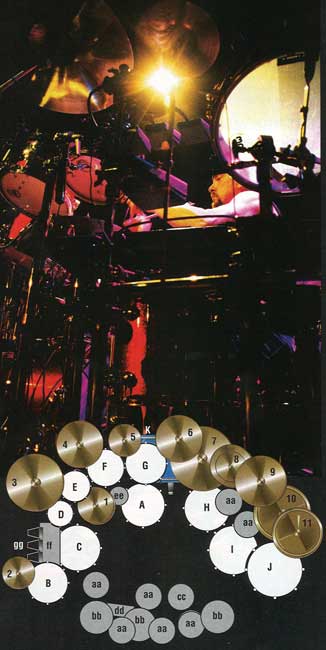

Victory Drums

A. 5x14 Craviotto snare

B. 4x13 piccolo snare

C. 13x15 tom

D. 7x8 tom

E. 7x10 tom

F. 8x12 tom

G. 9x13 tom

H. 12x15 tom

I. 16x16 tom

J. 16x18 tom (suspended)

K. 16x22 bass drum

Cymbals: Zildjian

1. 13" New Beat hi-hats

2. 10" A splash

3. 20" A crash

4. 16" A crash

5. 10" A splash

6. 16" A crash

7. 22" A Ping ride

8. 14" A Custom hi-hats with 8" splash on top

9. 18" A crash

10. 20" China low

11 . 18" Wuhan China

Electronics: Roland V-Drums, Emu 5000 samplers, Roland TD-10 brain with expansion card, Shark trigger pedal (positioned to the left of hi-hat)

aa. V-Drum pad

bb. V-Cymbal pad

cc. V-Cymbal hi-hat pad

dd. V-Drum kick pad

ee. Dauz pad

ft. malletKAT

Percussion

99. cowbells

Hardware: DW, including a DW 5000 double pedal with felt beaters (medium spring tension)

Heads: Remo coated Ambassador on snare batter (fairly tight tension, no muffling) with Diplomat on bottom, coated Ambassadors on tops of toms (medium tension, no muffling) with clear Ambassadors on bottoms, Pinstripe on bass drum batter with Ambassador logo head on front (medium tension, no hole in front head, no muffling)

Sticks: Pro-Mark 747 Neil Peart model (oak)

Drum Tech Extraordinaire: Lorne "Gump" Wheaton

Snare Drum Selection

By Neil Peart

I have said before, notably in my instructional video A Work In Progress, that I like to have a wide range of snare drums available in the studio. The choice of a particular snare for a song is influenced by several factors: the character of the song I'm playing and the drum part I have created for it, my taste in sounds, and the sonic environment of the room in which I'm playing.

The recording of Test For Echo was a graphic example, for I had chosen an array of snare drums during the pre-production process in a small studio, only to find that the big room at Bearsville Studios "required" a snare drum choice one degree brighter- i.e., a different drum.

For touring I use a "versatile" instrument that can cover all areas well, though even that is subject to change. For many years I depended upon an old Slingerland wood-shell snare for that purpose, but then it became supplanted by a DW Edge snare that combines wood and brass elements.

Now, as I rehearse for this Vapor Trails tour, I find that I've been favoring the DW Craviotto model, just because it sounds so good in the warehouse where I'm working. But again, that is subject to change when we move into full production rehearsals in an arena.

During the songwriting and pre-production work for the Vapor Trails album, as I played each of the songs to refine my part and its execution, I tried different snare drums from my ever-growing selection. Listening to the playback, I could compare how each one worked in a particular song.

I am fortunate that my tech, Lorne "Gump" Wheaton, has good ears for what I'm after. While the recording engineer is busy with the overall sound as well as each of the other details of sound and performance, Lorne will listen for the nuances of the snare drum as I play. Then, between takes, he will give me a reliable report on what the current candidate sounds like, and we'll discuss other options.

So given the above foundation, what follows is the selection of snare drums I used for each song on Vapor Trails. In that particular room, for those particular songs, the Yamaha Elvin Jones model proved to be the most versatile, showing up on more than half the tracks. (Though the wooden hoops that are a standard feature on the drum didn't survive my abuse . We switched to metal.) From the driving dynamics of "One Little Victory" and " Peaceable Kingdom" to the more rooted timekeeping of "Ghost Rider" and "Sweet Miracle," this drum was a joy to play, and obviously gave great results in the studio.

A similar versatility applied to the Yamaha bamboo shell, which sounded as crisp and bright as one would expect from that material, but still worked in the more sensitive role required in the song "Vapor Trail," for example (the intro to which also features "detail" work on a 13" DW piccolo, by the way).

I've always liked wooden piccolo snares, and it was a pleasure to find a use for the 14" DW model in "Earthshine," and the same with the 5x14 Craviotto snare that has become my current rehearsal mainstay, for it worked best on two of the tracks as well.

"One Little Victory" - Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

(with metal hoops, not standard wood)

"Ceiling Unlimited" - Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"Ghost Rider" - Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"Peaceable Kingdom"-Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"The Stars Look Down" -Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"How It Is"-Yamaha 5x14 bamboo

"Vapor Trail"-Yamaha 5x14 bamboo

"Secret Touch" - Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"Earthshine" -3'/2X13 DW maple piccolo

"Sweet Miracle" - Yamaha 7x14 maple Elvin Jones model

"Nocturne" -5x14 DW Craviotto

"Freeze" -5x14 DW Craviotto

"Out Of The Cradle" - Yamaha 5x14 bamboo

Ghost Rider

Riding the Healing Road

Within a ten-month period, Neil Peart suffered family losses so devastating that they left him a ghost-physically a man but with nothing inside: no hope, meaning, faith, or desire to keep living. One year after the first tragedy, Neil was literally choosing between life and his own death. Finally, all he could decide upon was motion. He got on his BMW R1100GS motorcycle, and over the next fourteen months rode 55,000 miles in search of a reason to live.

On a journey of escape, exile, and exploration, Neil traveled from Quebec to Alaska, down the Canadian and American coasts and western regions, to Mexico and Belize, and finally back to Quebec. While riding "the healing road," Neil recorded in his journals his progress and setbacks in the grieving/healing process, and the pain of constantly reliving his losses.

He also recorded with colorful, entertaining, and moving artistry the enormous range of his travel adventures, from the mountains to the sea, from the deserts to Arctic ice, and the dozens of memorable people, characters, friends, and relatives he met along the way.

Published by ECW Press (www.ecwpress.com), Ghost Rider is a bold brilliantly written, intense, exciting, and ultimately triumphant narrative memoir from a gifted writer and musician, who started out as a man reduced to trying to stay alive by staying on the move.