Rush's Neil Peart: Rockin' and rollin' ...rollin' ...rollin'

By Brian Catterson, Cycle World, February 2003, transcribed by John Patuto

It's seven minutes 'til sound check at Salt Lake City's Delta Center Arena and Neil Peart is on the phone with Ride West BMW in Seattle scheduling a service appointment for his R1150GS. Liam Birt, the rock band Rush's long-suffering tour manager, had poked his head through the tour bus door a few moments ago to make sure the band's drummer was "coming along," but the service manager just transferred Peart to the parts department, and now he's on hold pending word on whether the taller windscreen and driving lights he desires are in stock. Meanwhile, across the aisle, the band's security manager, Michael Mosbach, is seated at a computer calculating mileage for the following day's ride from Salt Lake City to Denver.

Such is life on the road with rock music's most acclaimed percussionist.

I'm here because I had contacted Jack David of ECW Press about getting a review copy of Peart's new book, Ghost Rider. An act wherein I disclosed the fact that I'm a lifelong Rush fan, having first seen the band perform live in 1978. this led to a phone call from Rush's publicist, Shelley Nott, who informed me that Peart is a devout CW reader, and had asked her to invite me to accompany him as he rode from once concert to another on the (Vapor Trails) tour.

"How does next week look?" I replied, doing my best to contain my enthusiasm. Noting that the band had a night off between Albuquerque and Salt Lake City shows, I suggested we meet there.

Agreeing, Shelley gave me Michael's cell phone number and we arranged to meet in Gallup, New Mexico, one week later.

In his book, Peart admits that he's always perceived concert touring as a "combination of crushing tedium, constant exhaustion and circus-like insanity." While he enjoys the planning and rehearsing in preparation for a tour, and the early shows as the band and crew strive for the perfect performance, once they've achieved that, the thrill is gone.

Motorcycling has made touring palatable again. "The good parts are lots of riding and I can eat anything I want because I drum for three hours every night," Peart says.

After which, most nights, it's a mad dash to the tour bus, where Neil and Michael snooze as bus driver Dave Burnett navigates through the darkness. In the morning they pull over, unload the bikes from the enclosed trailer in tow, and Neil and Michael ride to the next show, arriving early before the throngs; like we did this afternoon.

A late bloomer in motorcycling terms, Peart didn't take up the sport until the age of 41, when his wife Jackie bought him a BMW R1100RS for Christmas 1993. An avid bicyclist, he always suspected he'd enjoy motorcycling, but once the bug bit, Peart was infected, and quickly made up for lost time. He and his best friend Brutus rode all over Canada, and shipped their bikes to Mexico and Europe for Extended moto-vacations. And then, during the 1997 Test for Echo tour, the pair rode from concert to concert, clocking tens of thousands of miles as they visited 47 of the 47 contiguous United States.

Life was good: In addition to the new album, which Peart considered his masterwork as a drummer, he'd just completed his second Buddy Rich tribute album and an instructional video. Though always something of a cult band, Rush had by this point sold upwards of 35 million records, won a score of Canadian Juno Awards and been nominated for a Grammy three times. Perhaps most impressively, the three band members had been awarded the Order of Canada, the commonwealth equivalent of being knighted by the Queen.

And then, the music stopped.

On August 10th, 1997, Peart's 19-year-old daughter, Selena, was killed in a car accident en route to beginning her freshman year of college. His wife Jackie never recovered from that emotional blow, and just 10 months later, she passed away, too. "The doctors called it cancer, but of course it was a broken heart," Peart later wrote.

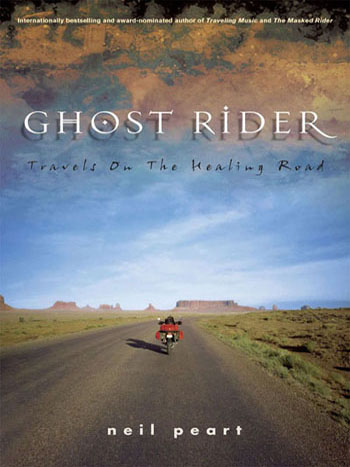

Suddenly alone, and stricken with grief at the loss of his loved ones, Peart told his bandmates to consider him retired and set out on an epic 14-month, 55,000 mile motorcycle journey. A journey that ended happily when he met and ultimately married Carrie Nuttall, a fine-art photographer whose work, "Rhythm and Light" (www.carrienuttall.com) captures her husband back at work in the studio. Peart chronicled his adventures in Ghost Rider, and in a song by the same name on Rush's long-awaited new album, Vapor Trails.

That album is a milestone in that it marks the return of the man who Modern Drummer magazine voted "Best Rock Drummer" so many times he was finally retired to his own personal Hall of Fame. And the man who, during his self-imposed "exile" didn't touch the drums for two years.

Equally significantly, it marked the return of rock music's most thought-provoking lyricist, because while it's bassist Geddy Lee's voice that you hear, it's Peart's words; with rare exceptions, he's written every lyric since joining the band for their second album, Fly By Night, in 1975.

Taking his penchant for the written word to the next level, Peart in 1996 penned The Masked Rider, about a bicycle journey through West Africa. Though an entertaining read, with colorful imagery and no shortage of the author's thoughts and observations, that effort was rather impersonal - his family and band mates barely rated a mention.

In Ghost Rider, however, Peart bares his soul, candidly detailing his progress on what he calls "The Healing Road." A heady read destined to rank alongside Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, the book works on three levels, appealing to Rush fans, motorcycle tourers and, perhaps most importantly, to anyone who's ever suffered the loss of a loved one. Motorcycling, as many of us have come to know, is therapeutic.

How therapeutic, I'm in the process of finding out. We'd rendezvoused the previous morning at a truck stop off I-40 in Gallup. By this point, I'd been in touch with Peart's publisher, publicist, and security manager, but I'd not actually spoken to the man himself. And as I approached the tour bus door, there was only one Rush lyric on my mind. It was from a song called "Limelight" on the 1981 Moving Pictures album, about the harsh reality of fame: Living in a fisheye lens, Caught in the Camera eye, I have no heart to lie, I can't pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend.

And so it was with a apprehension that I knocked. An anxious few moments passed, and then Neil himself threw open the door and greeted me with a warm handshake and a smile. He quickly proved to be an educated CW reader, a fan of Kevin Cameron and well aware of Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis' exploits in the Dakar Rally and my reputation as the staff Italophile-never mind that I was aboard a BMW F650GS for this outing. Neil himself had owned a Ducati 916, which he kept parked in the living room of his lakefront home in Quebec, but had traded it in along with a K1200RS to purchase his current mount. He kept the original Christmas present RS for sentimental reasons, and the R1100GS he rode during the making of Ghost Rider now serves as a backup bike, parked alongside his and Michael's newer R1150GSs in the trailer.

Not surprisingly, the TV in the bus was tuned to the Weather Channel. Looking at the forecast, I noted that it read "Ceiling Unlimited" - title to one of the songs on Vapor Trails.

"Yes, that's where that came from," Neil said, smiling. "You're the first person to make that connection."

"So, what's the plan?" I asked.

"Well, I've never been to Canyon De Chelley, so I'd like to go there first," he replied.

I actually figured we'd be going there, since Neil wrote in his book that he'd been turned away by bad weather during a previous attempt.

We saddled up, then headed north and west, back across the Arizona border (for me) and up into the barren grasslands of the Navajo Nation. We paused at a couple of canyon overlooks, then departed to the northeast, taking the dirt turnoff for route 13 - a number that we should have regarded with the customary suspicion.

A mile or so up the road, we encountered a construction crew that was preparing to pave the road. A series of large highway markers stood in a row, and the three of us began slaloming between them. the party ended abruptly when the dirt turned to slippery mud, a water truck having just done its thing. We pressed on - carefully - and eventually returned to pavement, where we were marveled at the fact that we would probably be the last motorcyclists to ride that road in "unimproved" form.

We continued in the dirt on Route 63, only to have the main road dead-end, symbolically, at a cemetery. So we turned back and took the path less traveled, which quickly deteriorated from graded dirt road, to two-track jeep road, to single-track. It then merged with a sand wash, whereupon Michael's rear wheel promptly sank up to the axle.

I snapped the obligatory humiliating photo with my new digital camera, and then we headed back the way we came, turning the other way at a fork. The day before, my younger brother Paul had said to me, "Whatever you do, don't hurt Neil. I have tickets for the Madison Square Garden show." Those words reverberated through my head as I watched Neil's BMW slither sideways climbing a rise and then fall over, pitching him over the top and back down the hill!

Fortunately, the desert sand broke his fall, and Neil emerged unscathed. And not the least bit embarrassed, because he encouraged me to snap another photo before righting his bike.

"Do you guys always ride like this?" I asked.

"No, the only time I've ever ridden off-road in the desert was in Baja, and when Brutus and I tried to cross the Sahara," Neil replied.

Forging on, we arrived at a rocky ledge, from where we spied a graded dirt road leading to a highway on the horizon. And so we eventually made our way back to "civilization."

By now it was late afternoon, and we still had a couple of hundred miles to go to Moab, Utah, our evening's destination.

"If there were a show tonight, we'd be calling in a chopper right about now," remarked Michael. He carries a satellite phone for just such emergencies, but so far, the worst the pair has suffered is a ruptured oil line.

With Neil leading we high-tailed it to Moab, covering the distance in little more than two hours.

"You said your 650 cruised comfortably at 95," he told me later, "so I took you literally."

"Actually, I think I said 85," I replied, "but I stand corrected."

Our accommodations for that evening were at The Gonzo Inn (expensive - and worth it), where we were booked under the aliases Waylong Smithers and Nelson Muntz, Simpsons characters. Security is a never ending concern for musicians of Peart's stature - especially when they're as intrinsically private as he is.

"Neil wants to be known for his hands, not his face," offered Michael.

And privacy is more important than ever in the wake of Peart's recent "sabbatical." to avoid having to re-live past events over and over, he currently isn't doing any "meet and greets" with fans, or granting any interviews. As Shelley told me, "Cycle World and Modern Drummer are it."

Neil gave me a copy of the September, 2002, issue of Modern Drummer with him on the cover, and I read it at my first opportunity. According to the author, William F. Miller, Peart is a changed man. "

"In my many get-togethers with him in the past, there was never any sense of weakness or vulnerability. The old Neil was driven, self-assured, strong, brilliant and at times a tad aloof. He's different now. Brilliant? No doubt. Confident and strong. Perhaps. Aloof? No way. There's a greater sensitivity in him today, a look of compassion behind the eyes. Neil Peart has emerged from tragedy an even greater human being."

Strong words, and ones for which I have no basis for comparison. but in my two days of paling around with Neil, he struck me as a happy go lucky guy - polar opposite of the nerdy intellectual I'd envisioned while listening to previous radio interviews. Not to mention a gracious host: He and Michael picked up my hotel room, meals, gas...my money was no good, they said. "You're our guest." And so in one evening, I recouped all the money I'd ever spent buying Rush records - first on vinyl, then on CD. The concert ticket score would be settled by the "All Areas" laminated pass that Michael had given me that morning, with the words, "You must be special, because NOBODY gets one of these."

I certainly felt special. We had dinner at a restaurant that Neil had discovered during a previous visit, predictably talking about music and motorcycles, each obviously curious about the other's "gig." At one point, I noted that Neil had been into cars, cycling and now motorcycling.

"What's next," I asked.

"Nothing," he replied. "Motorcycling is it."

A "serious" journalist, if afforded this opportunity, would no doubt have asked The Big Question, something to do with the unfortunate turns that Neil's life had taken. But I couldn't do it. Reading his book, I got the sense that he'd had enough sorrow to last two lifetimes; he didn't need me to bring him down.

And maybe it was the wine, but as we talked about past albums and concerts I could feel myself regressing, the inquisitive journalist replaced by the teenage Rush fan I used to be. A teenage Rush fan sitting across the dinner table from Neil friggin' Peart.

It was a memorable evening. After dinner, we walked down Moab's main drag, ducking into the Back of Beyond Bookstore, where on Neil's recommendation I purchased a copy of Desert Solitaire, a superb novel about author Edward Abbey's experiences as a park ranger in the nearby Canyon lands National Monument. Or "Money-mint," as he called it.

We then retreated to Neil's suite for a nightcap of the Macallan, poured from the flask made famous (or infamous) in Ghost Rider. Noting our upscale surroundings, Michael remarked that because the other two members of Rush travel in private jets that cost 10 times as much as Neil's bus, the management company lets him splurge on hotels.

The next morning, we had a lazy breakfast at a converted jailhouse, then took the scenic route to Salt Lake City over to Route 191. It was my turn to lead now, and not having ridden many twisty roads the previous day, I took it easy at first, unsure of my companions' skills. but I needn't have worried because both turned out to be very capable.

This stands in marked contrast to the story Peart tells in his book. The spring after Jackie gave him the R1100RS, he and Rush guitarist Alex Lifeson (who had just bought a Harley) enrolled in a new-rider course, and Neil failed on his first two attempts. Despite being one of the world's preeminent drummers, Peart insists he's actually quite uncoordinated, and has convinced himself that drumming is really more "dis-coordination." This struck me as humorous considering that my brother Paul had just taken an MSF course, and told me that the instructor had stated that riding a motorcycle is "a lot like playing the drums." Yeah, says who?

In Price, bus-driver Dave joined us on Neil's old R1100GS and led us on the final leg of our journey into Salt Lake city. We arrived at the Delta Center early that afternoon, and Neil and Michael got straight to work - changing their oil!

"Ah, the life of a rock star," I remarked as I watched. "If ever there were a term that I despise, that's it," Neil shot back. He prefers the unadorned title, "musician."

Oil change completed, Neil escorted me inside, introducing me to Alex, Geddy, manager Ray Daniels and the various members of the 50-member crew. He took me up on stage, where I snapped a photo of him wearing a CW cap behind his drum kit, then invited me to have a seat on the stool. I declined on the grounds that it was "his" place - and besides, I'm a bass player, not a drummer. I didn't tell him that, though, figuring that telling Neil Peart you played an instrument would be like telling Valentino Rossi you rode a motorcycle.

We then went backstage to the dressing room.

"Make yourself at home," Neil said. "Sound check is at 5:30. If you need anything, I'll be in the bus."

I showered, changed into my street clothes, then headed back to the bus, where Neil was on the phone and Michael on the computer. Neil finished inscribing a copy of his book for me, and then we hurried inside for sound check, where I grabbed one of the 15,000 empty seats in the arena and watched, an audience of one. We then adjourned for dinner in the dressing room - just Neil, Alex, Geddy and me. I felt like the fifth Beatle, the talent less one.

Grabbing my digital camera, I showed the photos of the previous day's "desert crossing" to Alex and Geddy, remarking that if they knew what Neil was really doing on his bike, they'd make him ride in the bus.

Geddy smiled and said, "We couldn't stop him anyway."

Time came for the show, and with Neil planning to depart immediately after the final cymbal crash, he invited me to come backstage during intermission to say our goodbyes; which I did. We shook hands, he encouraged me to keep in touch via e-mail, and then, out of the blue, said, "Aw, give old Neil a hug." So much for that whole "stranger" thing...

At the end of his book, the Ghost Rider symbolically rides off the end of the Santa Monica Pier, never to be seen again. Peart, though, is still riding. Truth be told, he's been riding with me for years - seldom have I traveled without a Rush CD in my case. But it was nice to finally get a chance to ride with him.